War Between the States of Being (original) (raw)

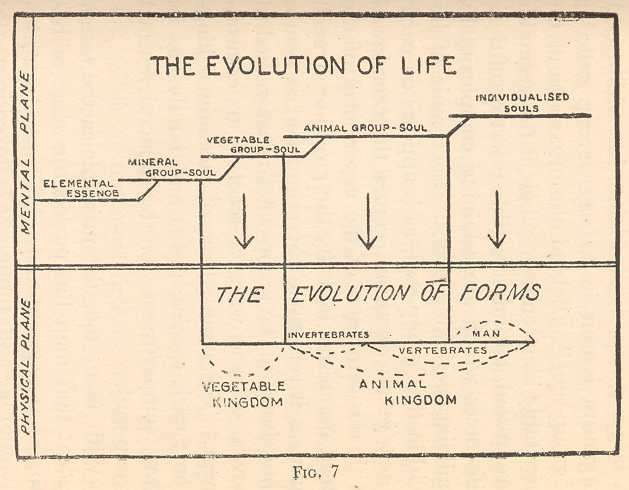

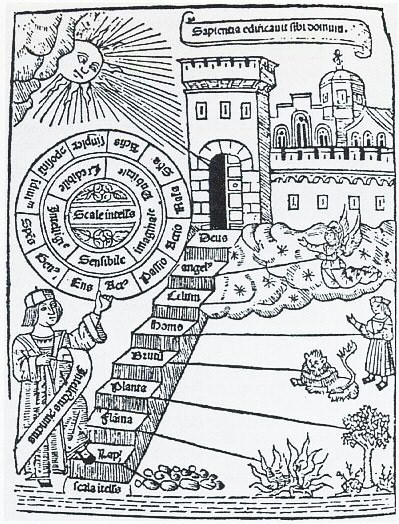

Erica Olivera’s presentation on Theosophy and its influence on L. Frank Baum at the latest OzCon included some information on the four kingdoms, those of mineral, vegetable, animal, and human. The animal-vegetable-mineral division is part of general knowledge, as well as being used in Twenty Questions, even as science has determined that it leaves a lot out. It dates back at least as far as Aristotle, who categorized various sorts of animals, and devised the idea of the Great Chain of Being, in which some natural beings are higher than others.

Minerals are the lowest, then plants, then animals, and finally humans. The animals themselves were ranked by complexity, by how energetic Aristotle determined them to be, and whether they had blood, although these groupings were generally approximate. Like many of Aristotle’s ideas, it was later adopted by the Christian Church, despite its creator being pagan. Of course, the Church ranked God and other divine beings higher than humanity, although it was argued that humans showed signs of divinity that the animals lacked.

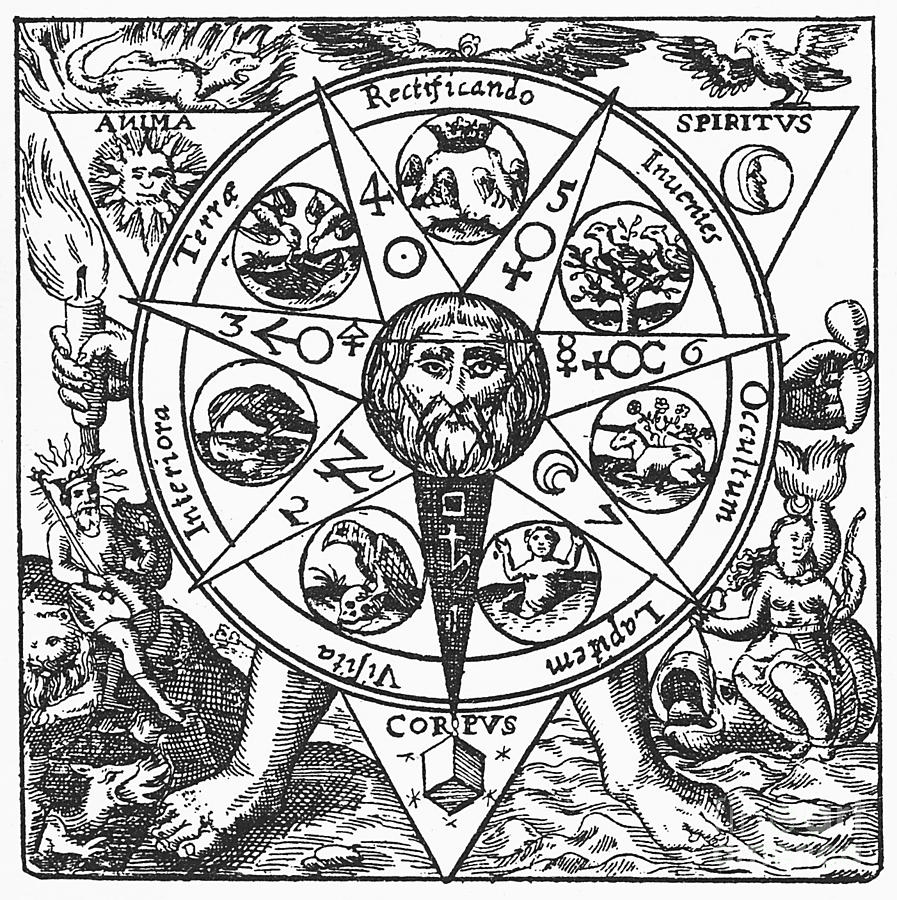

There were also ranks within the larger classifications, including the different orders of angels and kings using the system to declare themselves naturally higher than their subjects. Well, it is a CHAIN of Being, after all. Alchemy also used the Great Chain of Being as a way of claiming that all substances are interconnected, so you should be able to turn one into another.

I guess theoretically you could, if you could manipulate the atoms. When Carl Linnaeus developed his taxonomy, he used animal, vegetable, and mineral as the three kingdoms, grouping humans as animals because they clearly have the same traits.

Since then, the system has been altered to only include living things, but as we’ve discovered organisms that aren’t animals or plants, it changed into either five or six kingdoms, depending on whether or not you group all bacteria into one. The other two are fungi and protists. This is basically what I learned in school, but there are constant new developments, with some biologists arguing that the kingdom idea is obsolete.

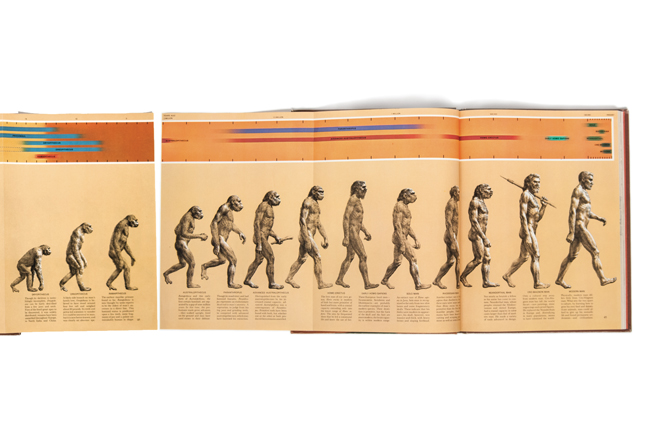

The Chain of Being still persists in the view that evolution is a progression from lower to higher forms, even though this isn’t really what science indicates. I’ve heard that Charles Darwin didn’t much care for the term “evolution,” as it suggests progress rather than change to fit the environment. Creationists like to insist that evolution is a religion, which is nonsense from a scientific perspective, but does at least somewhat fit with orthogenesis. It’s still thought that the earliest forms of life were quite simple, so you could say there’s progression in terms of complexity (although obviously not always), but does that necessarily make one organism higher or lower than another? Theosophy is one of many belief systems to incorporate the Great Chain of Being along with some more scientific concepts, and Baum plays on the idea with the disenchantment of Prince Bobo in Rinkitink in Oz, which comes across as pretty racist to a modern audience. Tottenhots, based on the Khoikhoi of southeastern Africa, are described as “a lower form of a man.” I’ve noted the connection to scientifically unsupported racial evolution, and John R. Neill’s illustrations parody the progressive view of evolution.

As such, it’s interesting that an ostrich is a step in the right direction from a lamb because it has two legs instead of four, even though humans are mammals. But then, transformational magic doesn’t necessarily work along the same lines as taxonomy.

I know I’ve seen it noted before that Dorothy’s Ozian companions on her first adventure (so not counting Toto) represent animal (the Cowardly Lion), vegetable (the Scarecrow), and mineral (the Tin Woodman). Of course, they’re all capable of thought and movement, which kind of puts a damper on the idea of any one of them being higher or lower. Throughout the Oz series, magically animated beings argue amongst themselves and with flesh-and-blood creatures which are superior, but there’s never a clear winner.

We can also link the natural kingdoms to other sorts of characters. The Nomes are linked with minerals, but at the same time, they’re rational beings with emotions and a sense of morality. Sure, it might not always match what mortals think, but it’s still there. On the other hand, when Dorothy and the Wizard of Oz visit the literal Vegetable Kingdom, a play on words as it’s a country with a ruler (although since that’s first a prince and then a princess, maybe Vegetable Principality would be more accurate), the inhabitants are incapable of love and compassion, although they do have enough sense to run an ordered society. So are the vegetables lower than the minerals in the sense of self-actualization? I’m not sure that was really the intent. By the way, Dick Tater in Neill’s Scalawagons refers to himself as “the greatest Potentato of the Vegetable Kingdom,” but it’s presumably not the same one as the Mangaboos’ land. Maybe the potatoes are one of Helena Blavatsky’s root races.

Unlike in the Return to Oz film, Baum’s Nomes aren’t MADE of rocks; they just have an affinity for them.

They’re classed as fairies, which in a way could make them higher than humans, if obviously not in terms of where they live. Nomes were inspired by Paracelsus’ elementals, who were associated with the four classical elements. Elementals in Theosophy are described as the life force of the elements, seemingly capable of a sort of intelligence or at least able to reflect human intelligence, but without morals or a definite physical shape. While some of Baum’s immortals could change form, not all of them could. Most of them are good, although some can be nasty, like the old Nome King; and even he isn’t totally devoid of morality. And as I wrote last week, they’re also generally limited by their physical bodies. So, while Baum was likely introduced to some of these ideas through Theosophy, he obviously put his own spin on them.