Huluppu to Hell (original) (raw)

Alice K. Turner’s The History of Hell gave glimpses into a lot of different myths associated with the world of the dead, some of which I don’t think I’d really explored before. Two of them were Mesopotamian stories, that of the marriage of Ereshkigal and Nergal, and that of Inanna and the Huluppu Tree, both of which relate to the Underworld.

Ereshkigal, goddess of the dead, also features in the story of Inanna or Ishtar’s descent into Irkalla (the underworld) to save her husband Tammuz, or maybe just because she feels like it.

The sisters were hardly on the best of terms. The other story of this goddess has her unable to attend a banquet of the gods, so she sends her son and messenger Namtar.

When Nergal, the god of war and plague, acta disrespectful toward Namtar, his mother demanda that Nergal face her in the underworld. In one version of the story, Nergal brings along some demons to help him through the gates of Ereshkigal’s domain, then threatens the goddess with an axe until she offers to be his wife. Another gives her more agency, saying that she seduces him after Enki specifically tells him not to have sex with her. He also warns Nergal not to sit, eat, drink, or bathe while in the underworld. Unlike Persephone, he apparently has no problem with these, but can’t keep his libido in check. Like Tammuz and Persephone, he’s sometimes said to spend half his time in the underworld and half outside it, but does appear to have a great deal of power over his wife’s realm. And his becoming Namtar’s stepfather was probably rather awkward.

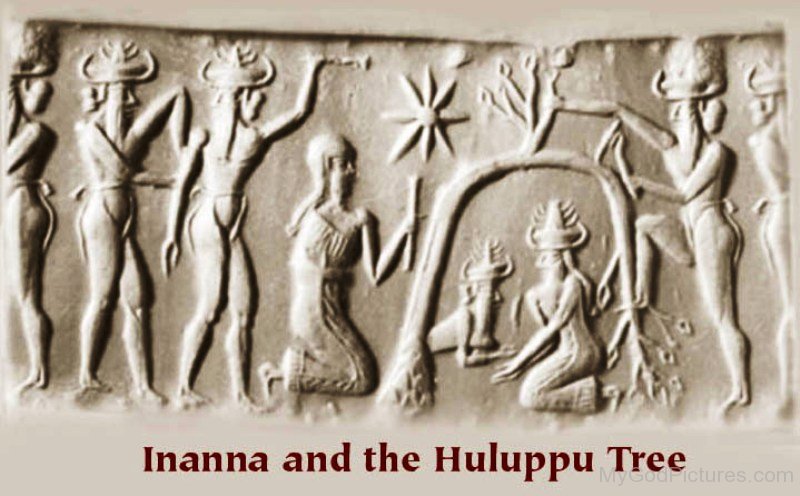

The other tale was found on the twelfth tablet of the Epic of Gilgamesh, and is about the legendary hero, but is inconsistent with the main story. It’s probably a separate myth that was placed with the others because of the similar theme. It starts at the creation of the world, with a huluppu tree (a willow or poplar, from what I’ve seen online) being planted on the bank of the River Euphrates. The wind blows it down and it floats down the river, where Inanna rescues it and takes it to Uruk to plant. Like Thidwick the Big-Hearted Moose’s antlers, it becomes infested with unwelcome guests, a serpent in the roots, a storm bird in the branches, and the demon Lilith in the trunk. Lilith is a fascinating character who shows up in various sources long before she was identified as Adam’s first wife, and apparently the word could just mean an owl, but what fun is that? Anyway, Inanna asks Gilgamesh to drive out the pests, which he does, then makes a throne and bed for the goddess from the wood. She makes him what I’ve seen identified as a drum and drumstick, but translations differ; they might be a mallet and ball instead. When he drops them into the underworld, his sidekick Enkidu goes to get them, but he ignores Gilgamesh’s instructions about how to behave down there and has to stay dead. And yes, this is quite different from the account of Enkidu’s demise in the Epic. Also, Ishtar in the Epic is a total jerk to Gilgamesh when he refuses to marry her.

Anyway, Nergal allows Enkidu to briefly visit the world of the living as a ghost, and he tells his old friend about what goes on in Irkalla. This dialogue is fragmentary, but Enkidu relays the fates of several dead people, including one who is missing his hands and legs, one being eaten by worms, several who drink muddy water, and others who have more pleasant experiences and work with the gods. Still it’s no wonder Gilgamesh doesn’t want die.

This entry was posted in Animals, Babylonian, Mythology and tagged alice k. turner, demons, enki, enkidu, epic of gilgamesh, ereshkigal, gilgamesh, huluppu tree, inanna, irkalla, ishtar, lilith, namtar, nergal, persephone, serpents, tammuz, the history of hell, underworld. Bookmark the permalink.