Do the Wrong Thing (original) (raw)

I’ve been thinking a bit about morality in video games, partially due to seeing another mention of how the Grand Theft Auto games, and I think some others of the sort as well, let you brutally murder prostitutes and perform other unsavory acts. I’m not really familiar with gritty video games (by which I don’t mean games with the Flyers’ mascot, but if those don’t exist yet they probably will soon), but I’ve heard the arguments that they demean women and trivialize violence, which might be true to some extent. I suppose it’s more about reinforcing existing bad ideas than directly leading to people wanting to do such things in real life. Our society is already really crappy to sex workers even without the video games. It’s also possible that letting players do horrible things could be a way of blowing off steam. And sometimes it’s just fun to find the limits of what you’re allowed to do. I know I occasionally found it cathartic to have Sims beat each other up, and sometimes to kill them. But then, this was all pretty cartoonish, and it’s not like Sims could kill each other; the player does so by manipulating the environment.

There’s probably a difference when it’s realistic, and it’s not like all bad things are equally bad. A lot of games let you kill villains, even though you could make a valid argument that some of them don’t deserve it. I’ve heard that Undertale tacitly encourages not killing monsters. It’s much less common and more controversial to let you kill total innocents. Even in more family-friendly games, you can do some kind of nasty things. I’ve looked before at unsavory things you can get Mario to do. There’s a stage in Super Mario World where you can only reach a secret exit by sacrificing Yoshi, which is pretty sad even though he’s apparently able to regenerate.

The game doesn’t force you to kill Yoshi, but you need to reach that gate to have full completion, so is that a reward? If you drop the baby penguin off the cliff in Super Mario 64, you don’t get the star from that mission, but nothing bad happens either.

Maybe living in a world where things respawn gives everyone a rather relaxed attitude toward killing. But it’s interesting you can even do these things, unlike, say, shooting the dog in Duck Hunt, which seems to have been pretty universal even though very few people would shoot a real dog even if it DID laugh at them. In Super Mario Bros. 3, you can shoot fireballs in Toad’s face while in his house, but they don’t affect him. The game Maniac Mansion famously allowed you to microwave a hamster, even in early NES copies, although Nintendo’s censors eventually caught on and got rid of it.

There’s no advantage to cooking the rodent, and it can even work against you because Weird Ed will kill a playable character if you let him know about it. If there’s any result at all, however, whether good or bad, it means the developers considered players trying to do such things.

It’s interesting that Richard Garriott, AKA Lord British, designed Ultima IV as a specifically moral game, making the goal to excel in different virtues. The story is that, in earlier entries in the series, not only could you kill townspeople and steal from stores, but it was often easier to build up your characters that way. Even then, there were consequences; I only played a little of the NES version of Exodus, but I remember really tough guards coming after you if you tried to open certain treasure chests. They’d also show up if you fought townspeople.

If you were strong enough to kill the guards, though, you presumably could get away with it. Console RPGs generally simplified things somewhat, and as in other games, you just didn’t get the chance to do really terrible things. If you could fight something, you were supposed to do so, and were rewarded for killing it. All treasure chests you could get to were yours for the taking. And there was no way to steal from a store. Some treasures were inaccessible until you got permission to have them, making being heroic enforced by the programming. I did notice that, in Glory of Heracles, Leucos scolds the hero if he tries to take things from people’s cabinets, but I never found out whether it affects anything beyond that. And I remember in Secret of Evermore how there was a place in Ivor Tower where, if you didn’t take any of the treasures before talking to someone named Lance, he’d give you an alchemy formula. After that, you were free to take the treasures./Update%2023/109-image124.png)

I understand that, in Link’s Awakening, you can shoplift, but if you return to the same store the shopkeeper zaps you with electricity that instantly kills you.

At least in Ultima they left it to the authorities, although I know that’s not always better.

Your in-game name is also changed to “THIEF,” which is some Scarlet Letter kind of stuff. In the DX version, however, you have to shoplift once in order to complete the photography challenge.

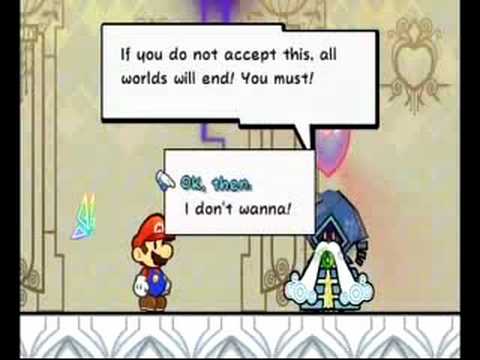

The Dragon Quest series is famous for giving choices that aren’t really choices, because you get stuck in a loop if you choose the wrong option. The “but thou must” bit with Gwaelin isn’t about morality (well, unless the hero led her on while you weren’t controlling him), but there are other not-really-choices that are. In DQ1, there’s only one totally wrong choice you can make, which is choosing to side with the Dragonlord upon reaching him, making you have to restart from your last save. There are similar choices in other games, the Paper Mario ones coming to mind. In The Thousand-Year Door, you can choose to side with the Shadow Queen, with the same result as in DQ1. And in Super Paper Mario, you can refuse to help at the very beginning of the game, which also results in a Game Over.

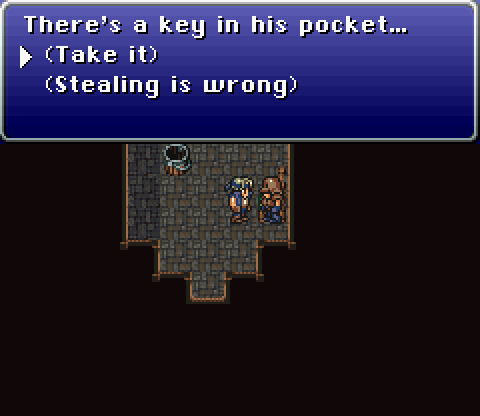

I suppose absolutely refusing to save the world is something out-of-character for Mario, unlike throwing a baby penguin off a mountain. With regards to stealing, it did come to mind that there’s a part in Locke’s scenario in Final Fantasy VI where choosing “stealing is wrong” makes it impossible for you to proceed, even though stealing generally IS wrong. Of course, this is a special situation. The lesson is, if you’re trying to free a prisoner from evil occupiers, maybe stealing is okay.