When the World and I Were Young (original) (raw)

Continuing on the theme of calendars from another recent post, I’ve done some investigation into different calculations of the age of the world. The Jewish calendar and the traditional Byzantine one both date from the Anno Mundi, or Year of the World, when they estimated the creation of Earth to have taken place. Of course, these figures are way off from the estimates given by modern scientists, but the methods they used don’t date back that far. The Mayan Long Count calendar also appears to date from the estimated beginning of the world, which would have been in 3114 BC, although that would have actually been the fourth creation.

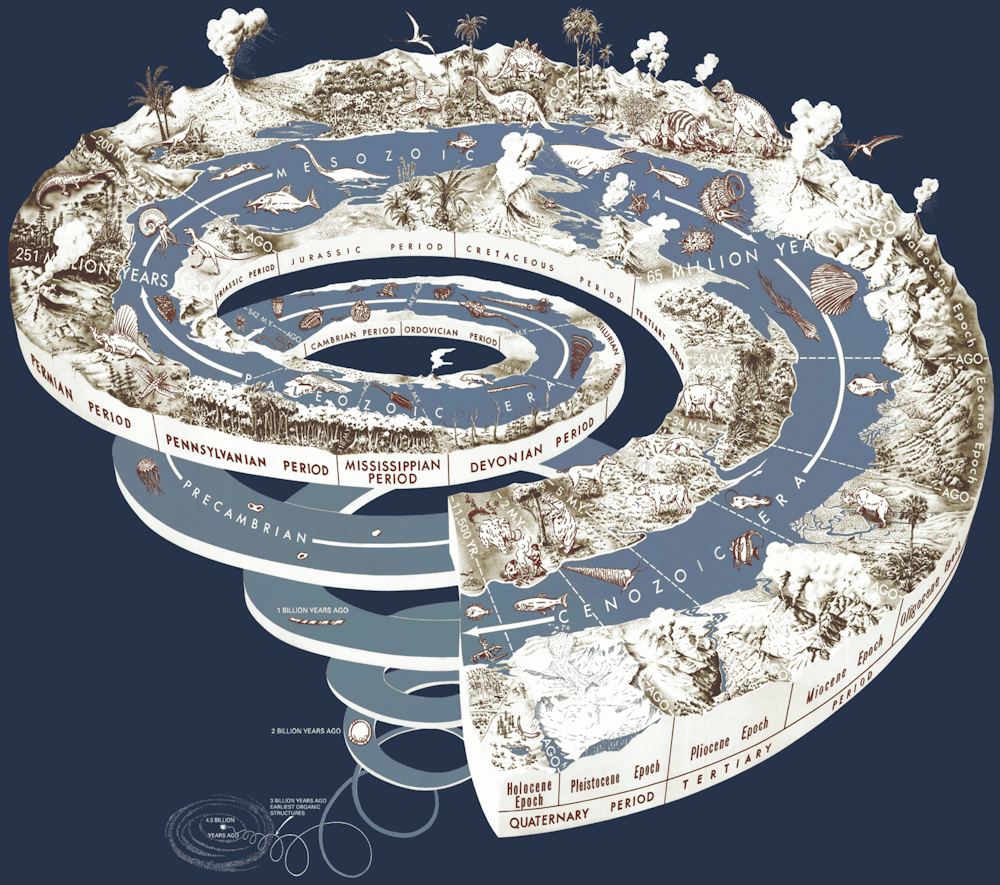

It was really only in the eighteenth century, due to advances in geology, that it became common to think of the planet’s age in terms of millions of years, let alone billions. I believe that’s also around when it was determined that the universe contained way more than our solar system, meaning the universe as a whole could be much older than the Earth. Even today, Young Earth Creationists still stick to the Biblically based estimate of around 6000 years, with the evidence otherwise being planted by Satan or a particularly capricious God to test our faith, or something like that.

I still think the shift from dinosaurs not having existed to their having lived alongside humans is just because kids think they’re cool.

The Bible does give a pretty consistent timeline, despite some significant contradictions. For instance, the length of time the Israelites spent in Egypt is sometimes given as 430 years, when adding up the ages of Moses and his ancestors back to Jacob’s son Levi gives a figure of way less than that. The 480 years from the Exodus to the building of Solomon‘s Temple as given in 1 Kings also doesn’t match with other books.

There are a lot of periods of forty years, which is a symbol for a generation or just a lot of something, so they probably can’t all be literal. There’s the general problem of determining dates based on people’s ages, as if a man, say, has a son at the age of thirty, that could be anytime from his thirtieth birthday until the day before his thirty-first. What might be the most significant, however, is the lack of context. For many of the patriarchs, all we get is a name and a lifespan, and many of those lifespans are absurdly long. I’m not even totally sure whoever came up with these genealogies was even trying to create a chronology. There’s a frequent theme in mythology of earlier ages when the world was more magical and there was less separation between humans and gods, and people living for centuries definitely fits with that. Compared to the Sumerian King List, which might have been an influence on the record of Biblical patriarchs, they’re really much shorter. The eight antediluvian kings are said to have ruled for a total of 241,200 years. There’s a similar document from Egypt, the Turin King List, believed to be from the time of Ramesses II, that tells of a time when the country was ruled by literal gods, some of whom reigned for thousands of years. And China has several legends about kings ruling for 18,000 years. There have been attempts to make these dates more believable, by saying they measure months instead of years or something like that, but I think that might be missing the point. With the Genesis chronology, another issue is the difference between the Greek Septuagint and the Masoretic Text, which give considerably different time periods for the antediluvian patriarchs. The Masoretic text wasn’t completed until around the tenth century, but it was based on earlier Hebrew sources, and became not only the standard in Hebrew but the basis for many Christian translations. When I read the Gospel of Nicodemus, I found the statement that the world was 5500 years old in Jesus’ time to be interesting, and this was derived from the Septuagint.

The Byzantine calendar used by the Eastern Orthodox Church is basically the same as the Julian, except it counts from September 5509 BC. The September date was largely chosen because it’s when the imperial government assessed new taxes every fifteen years, but there were other factors as well. The main competing date for the new year was 25 March, when Jesus was supposedly conceived. The Jewish year of creation, 3761 BC, was calculated by Rabbi Jose ben Halafta in the second century. The creation didn’t actually begin until the end of that year, with Adam being created on Rosh Hashanah, the first day of AM 2. We’re now in the Byzantine year 7530 and the Jewish year 5782. Western Europe tended to go with the world having been created around 5200 BC, but the historian Bede, who used some Jewish sources, thought 3952 BC was more likely. Since some people thought the world would end in the year 800 (which would have been AM 6000), it was a way to buy some time; but some monks accused Bede of heresy for deviating that much from the widely accepted figures. While I don’t know when it originated, there was a Jewish tradition that the rededication of the Temple by the Maccabees in 164 BC happened in AM 4000, and several other significant events in Jewish history also occurred in years with significant numbers.

Martin Luther placed the Apostolic Council mentioned in Acts in 4000, while Bishop James Ussher figured Jesus was born in that year. Since it was commonly thought in his time that Jesus was actually born around 4 BC, that meant a creation year of 4004 BC.

Looking at the Wikipedia page on different estimates for the time of creation is pretty fascinating. Zoroastrianism uses a chronology of 12,000 years, with the first 6000 years of that being the creation itself, Zoroaster being born 300 years after that, and the triumph of Ahura Mazda coming in the year 12,000.

The Hindu belief holds that time is cyclical, with the universe existing in periods of 4.32 billion years, each of which is a day to Brahma. That this is even in the same ballpark as modern estimates is quite interesting, not because it’s likely the ancient Hindus had access to more accurate ways of measuring such things (I’m sure most of this estimation involved a lot of guesswork), but because they had some concept of what John McPhee called “deep time” in 1981.

What I can’t find is any clear indication of when this figure was devised. It’s apparently in the Vishnu Parana, but that’s been dated to anywhere from 700 BC to 1000 AD. Even the eleventh century seems pretty impressive considering European estimates from the same time period, however. I believe Aristotle thought the world was eternal, but that wouldn’t have actually required any math. I understand India was always pretty advanced mathematically. The figures were determined by multiplying a whole lot of relevant numbers, so while I have no real knowledge on the subject, it seems fairly likely to me that whoever devised this didn’t START with the idea of billions of years, but eventually arrived at it after all that multiplying. I remember reading somewhere about how it seems strange how Young Earth Creationists talk about how God is infinite and eternal, but also seem to believe in a very simple, compact universe. If this is the case, then the Hindu concept of time shows more acknowledgement of how vast things would have to be when dealing with cosmic matters.