The Ozual Suspects (original) (raw)

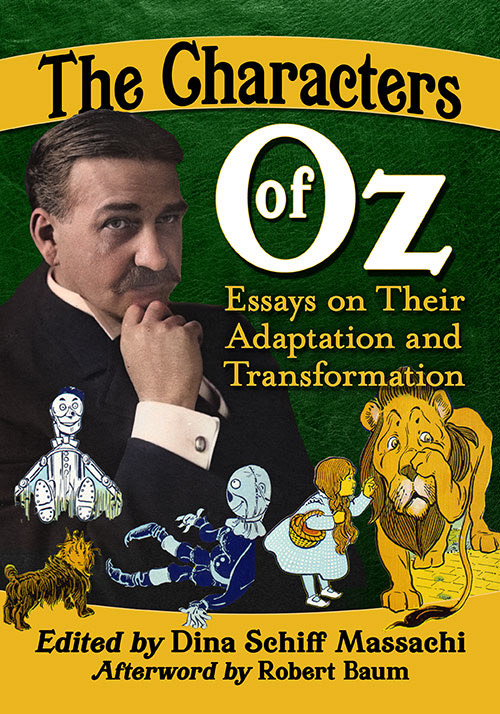

The Characters of Oz: Essays on Their Adaptation and Transformation, edited by Dina Schiff Massachi – This collection of essays by different authors, some of whom I know personally, discusses various Oz characters and how they’ve been used over time, both in the books themselves and in later media and popular culture.

- Mark I. West talks about Dorothy and her role as a traditional hero, and how the MGM movie made her less heroic and more passive.

- Katharine Kittredge discusses how the Scarecrow, the first normally inanimate being to be shown as alive in Oz, became more autonomous and social over time, and how darker interpretations show his natural curiosity as a bad thing.

- Dina’s first contribution is about the Tin Woodman and his emotional intelligence, and how he shows both traditional male and female roles. One of the few later adaptations that she thinks demonstrates this characterization is Todrick Hall’s Straight Outta Oz.

- Dee Michel and James Satter’s take on the Cowardly Lion also examines gender roles, in that lions are typically seen as symbols of aggressive masculinity, while this one is meek and gentle. MGM’s Lion (not the one in the logo) is specifically portrayed as stereotypically gay and a sissy by his own admission. Of Dorothy’s three Ozian companions, he’s the one who’s changed the most from the book, yet the essay points out that a fair amount of the dialogue from the first meeting with him made it into the movie. While I’m sure the flamboyant characterization was largely done for the humor, it’s also noteworthy that L. Frank Baum’s Lion is said to be particularly big and strong even compared to others of his kind and to have an intimidating roar, things which can’t really come across so well from a guy in a lion suit.

- J.L. Bell addresses the morality of the Wizard of Oz, how he initially seems correct in referring to himself as “a very good man,” despite his lies and tricks, and perhaps even more so his sending a little girl off to face a Wicked Witch. But in the original stage play, he’s a villain who exiles the King of Oz, and hints of this characterization make it into The Marvelous Land of Oz. When he returns to Dorothy and the Wizard, he’s back to being a mostly good guy. There’s also the question of whether his becoming a real wizard removes his contradictory characterization.

- Robert B. Luehrs discusses how the witches of Oz incorporate traits that had come to be seen as traditionally witchy, but also go against some of the common Christian beliefs of Baum’s day, and how he might have been influenced by his mother-in-law‘s writing on witches and magic.

- Dina’s second entry is about the Winged Monkeys, and how Baum wrote them as unwilling slaves of the Golden Cap, but adaptations would link them more explicitly with the Wicked Witch of the West and suggest that they’re serving her by choice, and make them scarier to boot.

- Walter Squire talks about Glinda as a maternal figure for Dorothy, a role Aunt Em was unable to fulfill, although she becomes much more loving toward her in later books. MGM exacerbated this by showing Aunt Em as unwilling to listen to Dorothy and stand up for her. Squire also points out how MGM’s Glinda demonstrates performative femininity, and appears dainty and scatterbrained but is still very powerful. And there’s a look at how Miss Piggy portrays all four witches in The Muppets’ Wizard of Oz.

- Mary Lenard ties Ozma and other female rulers in Oz to the fight for women’s suffrage, in a time when that was considered a pretty radical idea. It’s interesting that Baum himself wrote that women in government would create a “pure and just political policy,” which is something he tries to show with Ozma, who rules with kindness. But, as the essay points out, he also shows female rulers who aren’t at all kind, like the Queen of the Scoodlers and Coo-ee-oh. And I hadn’t really thought about how Mrs. Yoop and Reera the Red can be seen as being selfish in their domesticity, not using their powers to help others. Lenard also addresses how Baum shows that government should rely on the consent of the governed, as Matilda Joslyn Gage argued, while also making Ozma an absolute monarch. But that kind of thing is possible in fantasy.

- Paige Gray writes about how Jack Pumpkinhead is an essentially American character, and addresses the significance of pumpkins as well as the potential influence from Nathaniel Hawthorne’s “Feathertop.” She says that Jack is unnatural, but also comfortably familiar.

- Shannon Murphy’s essay on Jinjur makes an argument for the importance of her army fighting with knitting needles, and references how knitting has historically been used in feminist activism. She points out how Danielle Paige explicitly sexualized the army and had them use actual guns, which changes quite a bit.

- Angelica Shirley Carpenter examines the Nome King as a character who deserves more recognition, and as both a childish, humorous villain and a masculine tyrant in opposition to Ozma’s benevolent femininity.

- Finally, Gita Dorothy Morena, Baum’s great-granddaughter, writes of her own attachment to the Patchwork Girl, a strong-willed woman who values freedom. I wasn’t familiar with all of the later media discussed in the essays, but that didn’t hinder me that much. Oh, and I got an acknowledgement. I think that’s my third, all in Oz-related books.

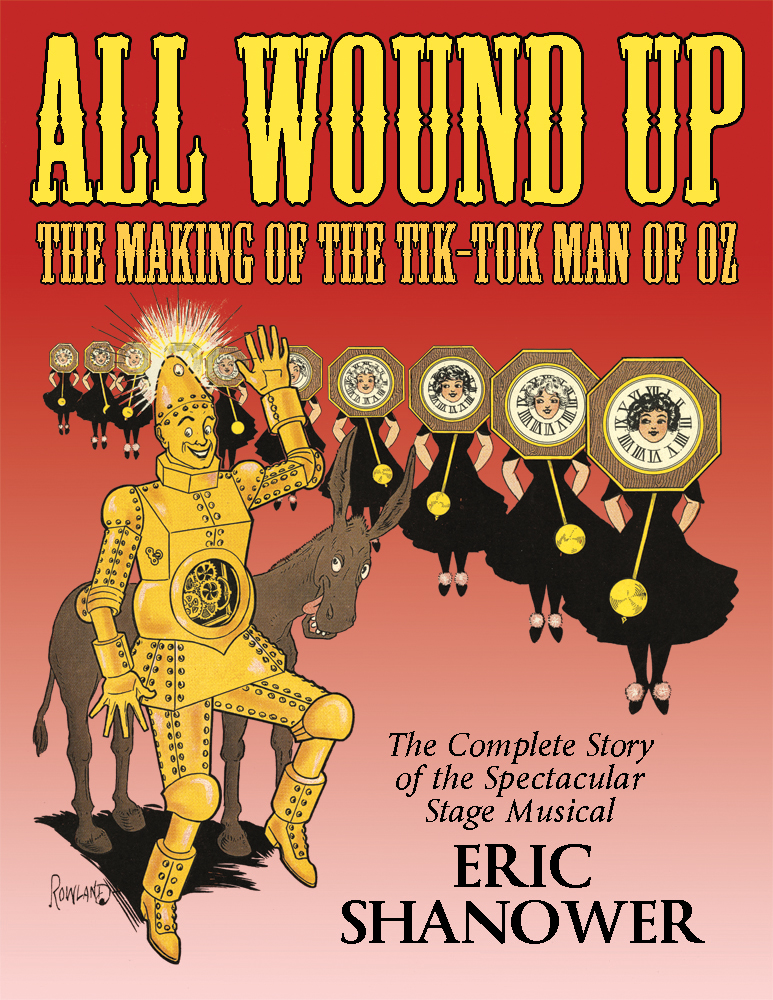

All Wound Up: The Making of The Tik-Tok Man of Oz, by Eric Shanower – It’s well-known that L. Frank Baum’s first love was the stage, and a musical version of The Wizard of Oz that opened in 1902 was a huge hit. It underwent a lot of revisions from how Baum originally imagined it, though, and he really wanted to come up with another success. The Tik-Tok Man of Oz, which opened in 1913, was moderately successful, but not as big as Baum had hoped. It started in Los Angeles and ran for almost a year, traveling as far east as Cincinnati, but never to Broadway.

Eric began doing research on the show after he and his partner David Maxine oversaw a revival at OzCon in 2014. I wrote a bit about a version of the script that showed up online eleven years ago. It’s largely based on Ozma of Oz (also the working title for the play), but includes elements both from other books, as well as plays Baum wrote that either failed or were never produced. The script was in the works for years, so it’s difficult to tell where some elements originated, like the characters of Polychrome and the Shaggy Man, as well as the Love Magnet. The Magnet is used in the play to create comedic situations with characters falling in love with each other, while in the books the love it inspires is more on the platonic side. I’m fascinated by the chart in the book showing what influenced what. It’s interesting that the script doesn’t mention Oz, although there is a character named Ozma, not the same as the one in the books. And the Nome King is instead called the Metal Monarch, leading to his being called by both titles in the later book Tik-Tok of Oz. Baum also used the Nome King scenario in Prince Silverwings and Rinkitink, and Ruth Berman wrote about some nineteenth-century operettas with Gnome Kings. “Tik-Tok Man” is kind of a weird name, as Tik-Tok is just his name, not what he is. Gregory Maguire did later use “tik-tok” to refer to all mechanical people.

The play was produced by Oliver Morosco, with Louis F. Gottschalk composing the music. It appears to have been very reminiscent of the Wizard play, but at a time when comic fantasy extravaganzas had largely fallen out of the public favor. There also wasn’t much of a push to market the show to children, as Baum hoped would happen. From the reviews quoted in the book, it sounds like the main draws were Fred Woodward as Hank the Mule and Charlotte Greenwood as Queen Ann Soforth.

It’s interesting to note how the scenario developed over time, as earlier versions have a vegetable princess named Ideala, a Gnome King named Maikarore, Private Files being somewhat psychic, and Shaggy having a wife and ten children. The volume includes a lot of media related to the show and biographical information on the people involved. Particular focus is given to Gottschalk and Woodward. I remember when I went to Green-Wood Cemetery and saw the grave of a composer named Louis Gottschalk, only to find that this was a different guy who wasn’t related to the Tik-Tok songwriter, whose burial place is in LA but isn’t marked. I suppose the show is a bit of a niche interest, but there’s a lot of interesting stuff for anyone curious about early twentieth century theater.

This entry was posted in Advertising, Art, Book Reviews, Characters, Christianity, Eric Shanower, Feminism, Gender, Humor, L. Frank Baum, Live Shows, Magic, Magic Items, Muppets, Music, Names, Oz, Oz Authors, Philosophy, Plays, Politics, Religion, Sexuality and tagged a good man but a bad wizard, a living thing, all wound up, angelica shirley carpenter, aunt em, but first there was a scarecrow, charlotte greenwood, cowardly lion, danielle paige, david maxine, dee michel, dina schiff massachi, dorothy and the heroine's quest, dorothy and the wizard in oz, dorothy gale, feathertop, fred woodward, gita dorothy morena, glinda, glinda and gender performativity, golden cap, hank the mule, heart over head, intelligence, j. l. bell, jack pumpkinhead, james satter, jinjur, katharine kittredge, knitting, louis f. gottschalk, love magnet, mark i. west, mary lenard, matilda joslyn gage, miss piggy, nathaniel hawthorne, nome king, oliver morosco, ozcon international, ozma, ozma of oz, ozma sorceresses and suffrage, paige gray, patchwork girl, piecing together the patchwork girl of oz, polychrome, prince silverwings, private jo files, queen ann soforth, queen coo-ee-oh, rinkitink in oz, robert b. luehrs, ruth berman, scarecrow, scoodlers, shaggy man, shannon murphy, straight outta oz, the characters of oz, the marvelous land of oz, the muppets' wizard of oz, the nome king, the proto-sissy the sissy and macho men, the tik-tok man of oz, the wizard of oz (1902), the wizard of oz (1939), the wonderful wizard of oz, tik-tok, tik-tok of oz, tin woodman, todrick hall, trading knitting needles for pistols, walter squire, wicked witch of the west, winged monkeys, witch's familiars or winged warriors, witches, witches wicked and otherwise, wizard of oz. Bookmark the permalink.