The Woodland Period, Southeast Archaeological Center (original) (raw)

NATIONAL PARK UNITS:

NATIONAL PARK UNITS:

Woodland sites have been located in Ocmulgee National Monument, Andersonville National Historic Site, Big Cypress National Preserve, Big South Fork National River And Recreation Area, Blue Ridge Parkway, Cape Hatteras National Seashore, Canaveral National Seashore,Cape Lookout National Seashore,Chattahoochee River National Recreation Area, Chickamauga And Chattanooga National Military Park, Cumberland Island National Seashore, Desoto National Memorial, Everglades National Park, Fort Frederica National Monument,Foothills Parkway, Great Smoky Mountains National Park, Gulf Islands National Seashore, Horseshoe Bend National Military Park, Mammoth Cave National Park, Natchez Trace Parkway,Ninety Six National Historic Site,Shiloh National Military Park And Cemetery,Stones River National Battlefield, Timucuan Ecological and Historic Preserve, Vicksburg National Military Park, and Wright Brothers National Memorial.

History of Investigations

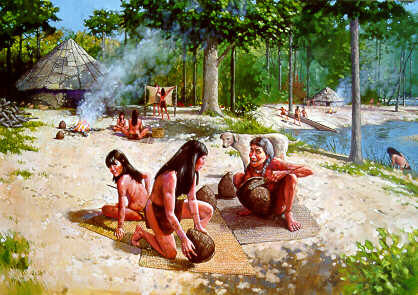

The term "Woodland" was introduced in the 1930s as a generic heading for prehistoric sites falling between the Archaichunting and gathering and the temple-mound-building Mississippiancultures in the eastern United States.

By the early 1960s, Woodland sites were generally characterized as those that regularly produced pottery and constructed burial mounds that contained elaborate grave goods. Although evidence was lacking, it was assumed that these burial mounds implied an agricultural-based economy to support the construction of these earthworks.

Traditional archeological interpretation of the evolution of prehistoric Native American cultures dictated that there was a clear line of division between Archaic peoples and Woodland pottery-making and agricultural peoples. By the mid-1960s, however, it was evident that in some areas of the United States prehistoric cultural groups with a clearly Archaic cultural assemblage were making pottery without any evidence of the cultivation of domesticated crops. In fact, it appears that hunting and gathering continued as the basic subsistence economy and that true agriculture did not occur in much of the Southeast for a couple of thousand years after the introduction of pottery.

In recent years archeologists in the southeastern United States have addressed the issue of agricultural development by investigating Woodland village sites to learn more about the subsistence patterns of the period. This has sometimes led to establishing cultural chronologies that separate Archaic from Woodland cultures with a transitional stage of cultural development, or to postulating alternative subsistence strategies for the cultures of the Early Woodland period in the Southeast.

In the Southeast, the Woodland period is now generally viewed as a cultural developmental stage or temporal unit dating from about 1000 B.C. to A.D. 1000. Rather than showing a wholesale change in material culture, archeology has shown a continuity in the development of Archaic and Woodland stone and bone tools for the acquisition, processing, storing, and preparation of animal and plant foods, leather working, textile manufacture, tool production, cultivation, and shelter construction. Some Woodland peoples continued to use Archaic-style spears and atlatls until the Late Woodland period (circa A.D. 800) when these were replaced by bow and arrow technology. The major technological change in the Woodland period, however, was the emergence of a distinct pottery-making tradition with definite vessel forms and decoration, although in the Southeast, pottery technology apparently began in the Late Archaic. There was also a culmination of an increasing sedentism, which first appeared in the Archaic, into permanently occupied villages.

Of importance was a realization that the subsistence economy of the Woodland period was essentially similar to that of the Archaic period, utilizing seasonal exploitation of wild plants and animals but with the introduction of a system of planting and tending of garden crops and the intensive collecting of starchy seeds and autumnal nuts. This set the stage for agriculture economies of the later Mississippian period. Generally, the Woodland period is divided into three subperiods. The beginning and ending dates for these phases, however, are not consistent throughout the Southeast.

Gulf Formational (2000 - 100 B.C.) and Early Woodland (1000 - 300 B.C.)

Gulf Formational (2000 - 100 B.C.) and Early Woodland (1000 - 300 B.C.)

If one uses the traditional definition of pottery introduction being equated with a Woodland tradition, then the earliest Woodland sites would be those found along the South Atlantic coast that have produced fiber-tempered pottery dating as early as 2500 B.C.

However, these sites are essentially Late Archaic seasonally occupied coastal base camps with a material cultural assemblage equivalent to that found on Archaic sites, and differentiated only by the addition of fiber-tempered pottery.

Researchers in the Southeast are attempting to define the beginnings of the Woodland period using not only the appearance of pottery but evidence of permanent settlements, intensive collection and/or horticulture of starchy seed plants, differentiation in social organization, and specialized activities, to name just a few topics of special interest. Most of these cultural aspects are clearly in place in parts of the Southeast by around 1000 B.C. The time period between about 2500 and 1000 B.C.should be considered a period of gradual transition from the Archaic to the Woodland.

Beginning around 2500 B.C., the Stallings Island culture established itself as a Late Archaic shellfish-collecting society that utilized the riverine and coastal environments, probably on a seasonal basis, leaving evidence of their occupation in the form of large shell middens. This cultural group used an Archaic material culture, but also created the first ceramics known in the United States. Called Stallings Island, these ceramics were named after a major shell midden site on an island in the Savannah River near Augusta, Georgia.

The Stallings Island ceramics generally contained Spanish moss as a tempering agent, and the forms consisted of simple shallow bowls and large, wide-mouthed bowls, as well as deeper jar forms. Most ceramics were plain, although some with punctated surface decoration were found. Stallings Island pottery dates from about 2500 to 1000 B.C., and ceramic finds range from the Tar River drainage in North Carolina, southward to northwest Florida.

Contemporary with Stallings Island pottery along the South Atlantic coast are other fiber-tempered wares, such as Orangeware from sites in northeast Florida and southeast coastal Georgia (1200 to 500 B.C.). Orange period sites have been located at Canaveral National Seashore, Fort Matanzas National Monument, and Timucuan Ecological and Historic Preserve. An unusual type of settlement pattern associated with fiber-tempered wares and found in this area are "shell rings." Nearly three dozen of these ring-shaped settlements have been identified as representative of permanent, stable village life by about 1600 B.C.

By 1000 B.C. fiber-tempered ceramic technology appears to have spread throughout much of the Deep South from the South Atlantic coast to the Okeechobee Basin area of South Florida. During the early Gulf Formational period (circa 2000 to 1000 B.C.) of Alabama, middle Tennessee, and eastern Mississippi, fiber-tempered ceramic technology was acquired as a by-product of trade between the Stallings Island and Orange cultures of the South Atlantic coast and the Poverty Point culture of the lower Mississippi River Valley. It was during the Gulf Formational period that fiber-tempered ceramics were replaced first by plain, then by fabric-impressed, and, later, by cord-marked sand-tempered Alexander ceramics.

Poverty Point sites in Louisiana and western Mississippi exhibit the first major residential settlements and monumental earthworks in the United States. Although the Poverty Point culture is not well understood in terms of social organization, it was involved in the transportation of nonlocal raw materials (for example, shell, stone, and copper) from throughout the eastern United States into the lower Mississippi River Valley to selected sites where the materials were worked into finished products and then traded. While specific information on Poverty Point subsistence, trade mechanisms, and other cultural aspects is still speculative, the sites nevertheless exhibit specific material culture, such as baked clay objects, magnetite plummets, steatite bowls, red-jasper lapidary work, fiber-tempered pottery, and microlithic stone tools.

In Arkansas, Kentucky, Tennessee, and North Carolina, fiber-tempered pottery from the 2500 to 1000 B.C. period is not usually found. This area appears to have functioned as a transitional cultural area through which ceramic influences from the Ohio River Valley and the Middle Atlantic were introduced into the Deep South. For example, northern-inspired grit-tempered plain, fabric-impressed, and cord-marked Early Woodland pottery first appeared in central and eastern Kentucky around 1000 to 800 B.C., and, by the end of the Early Woodland period (800 to 500 B.C.), it had replaced fiber-tempered wares throughout the Southeast.

With the introduction of these northern-type ceramics came isolated mortuary sites with grave offerings. Some of the best examples of earthen enclosures and burial mounds dating to the Early Woodland Adena complex (circa 500 B.C.) were identified in the Ohio River Valley of Kentucky. Early Woodland projectile-point styles from Kentucky include Kramer, Wade, Gary, and Adena. These new ceramics later appeared in the mountains of western North Carolina during the Swannanoa period (700 to 300 B.C.).

Although plant domestication occurred sporadically in the Late Archaic, even possibly as early as the terminal Middle Archaic, generalized plant domestication, or horticulture, appears in Kentucky throughout the Early Woodland with intensive collecting of starchy seeds and tubers. These appear to have included sunflower, maygrass, sumpweed, giant ragweed, and knotweed.

As already noted, the Early Woodland of central Tennessee, interior Mississippi, and Alabama, began with the introduction of fiber-tempered ceramics in the Gulf Formational period (around 2000 B.C.) from the South Atlantic coast Stallings Island and Orange cultures. By the mid-Early Woodland period, Gulf Formational cultures developed their own fiber-tempered pottery styles, such as Wheeler, which was in turn replaced by the sand-tempered Alexander series. This area also participated in long-range exchanges with other areas of the Deep South in steatite, sandstone, Tallahatta quartzite, and ceramics.

Eastern North Carolina, during the Early Woodland period (1000 to 300 B.C.), exhibits both Southeast and Middle Atlantic influences called New River and Deep Creek, respectively. The Early Woodland New River, found south of the Neuse River, appears to be a continuation of the Stallings Island, Thom's Creek, and Deptford cultures from Georgia and South Carolina. Meanwhile, north of the Neuse River, the Early Woodland Deep Creek culture produced Marcey Creek plain and cord-marked ceramics much like those from Virginia.

The Early Woodland Deptford ceramics appear to have developed in Georgia (circa 800 B.C.) out of the Early Woodland Refuge phase (1000 to 500 B.C.) and spread north into the Carolinas and south into Florida. Deptford ceramics continued to be made and found on Middle Woodland sites in the Southeast up through about A.D. 600. Subsistence for the coast and coastal plains of Georgia and the Carolinas appears to have followed a transhumant (or seasonal) pattern of winter shellfish camps on the coast, then inland occupation during the spring and summer for deer hunting, and fall for nut gathering.

In northern Georgia the appearance of Dunlap fabric-marked ceramics (circa 1000 B.C.) marks the beginning of the Early Woodland Kellogg focus. These types of ceramics are replaced by Middle Woodland ceramics (Cartersville plain, checked, and simple stamped) after about 300 B.C.

By around 500 B.C., the Poverty Point culture was replaced by the Tchula/Tchefuncte Early Woodland culture, which existed in western Tennessee, Louisiana, southern Arkansas, western Mississippi, and coastal Alabama. The sites of this lower Mississippi River Valley culture were small village settlements. Subsistence continued to consist of intensive collecting of wild plants and animals, as with the preceding Poverty Point culture, but for the first time quantities of pottery were produced. There appears to be a de-emphasis on long-distance trade and manufacture of lithic artwork noted in the earlier Poverty Point culture. The Tchula/Tchefuncte Early Woodland culture appears to have coexisted with some Middle Woodland cultures in the lower Mississippi River Valley.

The Middle Woodland (300 B.C. - A.D. 500)

The main characteristic, besides elaboration of burial practices, that distinguished the Early and Middle Woodland from Late Archaic traditions, was the gradual intensification of local and interregional exchange of exotic materials. For many years archeologists have regarded as "classic" those Middle Woodland sites with elaborate ceremonial earthworks that contained the burial mound graves of elite individuals buried with exotic mortuary gifts obtained through an extensive trade network covering most of the eastern United States. Because of the similarity of earthworks and burial goods found at widely scattered sites in the Southeast and the area north of the Ohio River, it was assumed that a cultural continuity-sometimes referred to as the Hopewellian Interaction Sphere-existed throughout much of the eastern United States.

Within the Ohio River drainage, the Early Woodland Adena culture, with its emphasis on elaborate mortuary customs, laid the foundations for the succeeding Hopewell (or Middle Woodland) culture.

Another way of interpreting the archeological manifestations of Middle Woodland burial mounds and elaborate burial goods obtained from distant sources may be as the result of reciprocal obligations and formal gift-giving between lineages or clans that controlled specific geographical territories. In this scenario, intensive exploitation of food or raw material resources in these areas, begun in the Archaic period, would lead to lineages or clans that controlled access to certain food or raw material resources important to, if indeed not necessary to, the survival of groups outside their territory.

Access to important food or raw material resources outside a clan's territory would be insured by formalized trade between the leaders of clans of different territories. The role of the clan head in this exchange system would be recognized by the group erecting burial mounds and interring exotic goods obtained through long-distance trade with other clan heads. At the same time, the social identity of these cultural entities would be reinforced by regular burial ceremonies at earthworks where important clan leaders were buried. Such a cultural system would increase social and economic stability between the clans participating in reciprocal trade. It would also reinforce trends toward sedentary living and the promotion of agriculture, which, in turn, would provide a surplus of food and lead to an increase in population.

Reciprocal trade, begun in the Early Woodland, would have served as a valuable cultural mechanism to spread the Hopewell (Middle Woodland) physical manifestations of earthworks and specialized burial artifacts throughout much of the eastern United States. As distinct territorial units entered into the trading sphere, their goods would be added to a pool of reciprocal trading items, and they would have access to goods unavailable in their own territory. At least some nonorganic trade items can be identified from the study of the burial mounds of the Middle Woodland. To this trade, the Middle Woodland territories of the Southeast appear to have provided mica, quartz crystals, and chlorite from the Carolinas, and a variety of marine shells, as well as shark and alligator teeth, from the Florida Gulf Coast. In exchange, the Middle Woodland clans of the Southeast received galena from Missouri, flint from Illinois, grizzly bear teeth, obsidian and chalcedony from the Rockies, and copper from the Great Lakes. Standardization of style for the finished artifacts used in this trade may be attributed to a relatively small number of clan leaders controlling the exchange system and developing their own symbolic artifact language of what trade goods constituted a reciprocal exchange between clans.

Most of the western and central Kentucky and western Tennessee Woodland cultures appear to have participated fully in the Ohio River Valley Early and Middle Woodland trading network. These cultures exhibited common burial practices and earthwork construction from the very start. Excavations in Kentucky have recovered Havana-like or Hopewell-decorated ceramics and Copena and McFarland projectile points. Burial offerings included gorgets, stone or clay tablets, tubular and biconical pipes, galena, mica crescents, copper bracelets, and marginella beads.

In western North Carolina, the early Middle Woodland Pigeon phase (300 B.C. to A.D. 200), noted for it crushed-quartz-tempered ceramics, was replaced by the Connestee phase (A.D. 200 to 600), which produced thin sand-tempered ware. Pigeon and Connestee components are present at Great Smoky Mountains National Park. The Connestee culture apparently was a major source of mica, quartz crystal, steatite, and chlorite schists for the Ohio Hopewell trade network. These were traded out for Tennessee cherts, Appalachian quartz crystals, Flint Ridge chalcedony of Ohio, and Chillico ceramics. Connestee ceramics have been found at Georgia, Ohio, Kentucky, and Tennessee sites.

Prior to about A.D. 1 most of the Deep South continued a Late Archaic style of seasonal rounds of hunting and gathering. This was supplemented by geographic specializations- such as riverine and coastal zone shellfish exploitation-and the planting and harvesting of some native plants. The Early Woodland and early Middle Woodland cultures of the Deep South are differentiated by a variety of regional ceramic styles. There appears to be limited direct contact between these cultures and Hopewell influences to the north. For example, Louisiana appears to have had contact with the Illinois River Hopewell during the Marksville times of the Middle Woodland. At the end of the Late Gulf Formational (500 to 100 b.c.), the interior area of Mississippi and Alabama adopted sand-tempered ceramics (Alexander) introduced from the north. There appeared to be some linkage between Middle Woodland cultures to the north through trade in locally available Tallahatta quartzite and Fort Payne and Camden chert. However, the subsistence activity of this culture was essentially Late Archaic in nature.

In northern Georgia, the predominant Middle Woodland ceramics are the Cartersville and Swift Creek series after about 300 b.c. The incorporation of western Georgia into the Hopewellian Interaction Sphere of Trade and the appearance of burial mounds only occurred from about A.D. 100 to 450. The exchange of materials associated with Hopewellian ceremonialism was restricted to western Georgia and did not appear to have spread, at this time, into eastern Georgia or South Carolina.

The Middle Woodland accouterments of burial mounds arrived later in the Deep South. In central Mississippi, the Miller culture (100 b.c. to A.D. 650) saw the introduction of burial mound ceremonialism, sand-tempered ceramics, and interregional trade from the Crab Orchard culture of western Kentucky and Tennessee and the Illinois Valley Hopewell. This area also received influence from the Marksville culture of the lower Mississippi River Valley. Some of the larger Miller burial mounds have produced Marksville pottery, galena, and copper earspools. Subsistence was based primarily on intensive seasonal hunting and gathering.

From the Early through the Middle Woodland periods, the extensive, low-lying coastal environment of the South Atlantic coast, stretching from North Carolina to northern Florida, was used by numerous Deptford hunter-gatherer bands who lived seasonally within a variety of ecosystems and took advantage of seasonally available foods.

Along the Gulf Coast, the Deptford culture continued the transhumant (or seasonal) existence throughout the Middle Woodland. Settlements in this geographical area lacked permanence of occupation, although the cultures here participated in the Hopewellian trading network to a limited extent and constructed numerous low sand burial mounds. These sand burial mounds along coastal Georgia and Florida (noted at Canaveral National Seashore and Cumberland Island National Seashore, for instance), as well as in the Carolinas, are believed to represent local lineage burial grounds rather than the resting place of an elite individual.

In northwest Florida, the Early Woodland Deptford culture evolved in place to become the Santa Rosa/Swift Creek culture. Trade items recovered from burial mounds include copper panpipes, ear ornaments, stone plummets, and stone gorgets. These show this area's incorporation within the Hopewellian Interaction Sphere by about A.D. 100.

The Marksville culture (A.D. 1 to 400) existed throughout the lower Mississippi River Valley and extended eastward along the Gulf Coast to the Mobile Bay area, an area that now incorporates Gulf Islands National Seashore. Marksville culture showed marked similarity with the contemporary Hopewell culture of the Illinois River Valley, particularly in the emphasis on earthworks containing burial mounds and the interring of exotic trade goods with the dead. Among the exotic trade items recovered by excavations in both areas were copper panpipes, earspools, bracelets and beads, stone platform pipes, mica figurines, ceramic figures, galena, marine shells, freshwater pearls, and green stone celts. The quantities of exotic trade material found in Marksville sites, however, indicate only minimal contact between the two areas.

Marksville sites tend to be located on major waterways. Subsistence consisted of intensive hunting and gathering, with some suggestion of maize horticulture. Although the current view is that there was no economically important horticulture during Marksville times, it appears the Marksville culture represents an in-place cultural evolution from the Archaic through the Woodland periods with selective adoption and reinterpretation of Hopewellian ideas.

In the interior of the Deep South during the Middle Woodland period, one sees the permanent occupation of small- or medium-sized villages along major rivers (Ocmulgee National Monument, for example), placing these settlements in the forefront of the expanding Hopewellian trading sphere along water courses. Between A.D. 1 and 450, these interior sites joined the Middle Woodland trading sphere as shown by the construction of hundreds of low oval mounds, many containing traded material from the Ohio Valley or the southeastern seacoast.

The rest of the continental southeast was only marginally affiliated with the Hopewellian Interaction Sphere. The St. Johns culture area of east and central Florida developed its own unique culture between 1200 B.C. and A.D.1565. This was exhibited by a number of sites in Canaveral National Seashore, Castillo De San Marcos National Monument, Fort Matanzas National Monument, and Timucuan Ecological and Historic Preserve. The St. Johns culture evolved in place from the Late Archaic Orange culture. Subsistence showed little in the way of agriculture, with the majority of food coming from seasonal plant food collecting, hunting, fishing, and shellfish gathering. This basically Archaic subsistence economy was able to support prehistoric Native Americans for 2,000 years until contact with Europeans. The St. Johns culture was largely unaffected by Hopewell influences, although they did construct sand burial mounds, a few containing Hopewellian-like grave goods.

The Manasota culture (500 B.C.to A.D. 800) of the Central Peninsular Gulf Coast of Florida, like the St. Johns culture, subsisted by plant-food collecting, fishing, hunting and shellfish gathering. The Manasota culture appears, as well, to have evolved in place from the local Late Archaic culture. At the beginning of the Manasota culture (500 b.c.), burials were interred in the shell midden of the villages. By 400 b.c., however, sand mounds for the interment of the dead were constructed. Later still (around A.D. 600), elaborate imported burial gifts were interred with the dead. Finally, the Manasota culture began to construct simple burial mounds that contained Weeden Island pottery (A.D. 800).

The Lake Okeechobee/Kissimmee River basin of south central Florida saw the construction of major earthworks between 1000 b.c. and A.D. 200 for horticultural purposes rather than as true burial mounds. By A.D. 200, this area was incorporated in the Glades culture area, which today contains Big Cypress National Preserve, Biscayne National Park, and Everglades National Park.

Beginning around A.D. 1, the Glades culture of south and southeast Florida represents a transitional culture from the Archaic. By A.D. 800, distinctive Glades pottery, shell tools, and bone tools appeared, remaining essentially un-changed until contact with Europeans in the sixteenth century.

The Middle Woodland of the North Carolina coastal plain is represented by two cultures, the Mount Pleasant culture in the northern part of the state and the Cape Fear culture in the southern part. Both date from about 300 b.c. to A.D. 800. Ceramics for the Mount Pleasant culture are sand and grit tempered with fabric-impressed or cord-marked surface finish. Shell-tempered ceramics from the Mid-Atlantic area also occur.

Although the Cape Fear and Mount Pleasant culture ceramics are similar, the Cape Fear culture exhibits an extensive distribution of low sand burial mounds that represent an influence out of South Carolina. Many burials contain gorgets, arrow points, conch shells, and platform pipes. This area appeared to have had only limited connection with the Hopewell Interaction Sphere. A few Mount Pleasant sherds have been recovered from Fort Raleigh National Historic Site.

The Late Woodland (A.D.500 - 1000)

Around A.D. 500, the archeological record reveals a sharp decline in the construction of Middle Woodland burial mounds in the Hopewellian core area of the Ohio River drainage. The decline in the construction of burial mounds is accompanied by disruption of the long-distance trade in exotic materials and interregional art styles.

Traditionally, archeologists have viewed the Late Woodland (ca. A.D. 500 - 1000) as a time of cultural poverty. Late Woodland settlements, with the exception of sites along the Florida Gulf Coast, tended to be small when compared with Middle Woodland sites. Based on our present-day perspective, few outstanding works of prehistoric art or architecture can be attributed to this time period. Careful analysis, however, shows that, throughout the Southeast, the Late Woodland was a very dynamic period. Bow-and-arrow technology, allowing for increased hunting efficiency, became widespread. New varieties of maize, beans, and squash were introduced or gained economic importance at this time, which greatly supplemented existing native seed and root plants. Finally, although settlement size was small, there was a marked increase in the numbers of Late Woodland sites over Middle Woodland sites, indicating a population increase. These factors tend to give a view of the Late Woodland period as an expansive period, not one of a cultural collapse.

The reasons for possible cultural degradations at the end of the Middle Woodland and the subsequent emergence of the Late Woodland are poorly understood. There are several possible explanations. The first is that populations increased beyond the point of carrying capacity of the land, and, as the trade system broke down, clans resorted to raiding rather than trading with other territories to acquire important resources. A second possibility is that a rapid replacement of the Late Archaic spear and atlatl with the newer bow-and-arrow technology quickly decimated the large game animals, interrupting the hunting component of food procurement and resulting in settlements breaking down into smaller units to subsist on local resources. This ended long distance trade and the need for elite social units. A third possible reason is that colder climate conditions about A.D. 400 might have affected yields of gathered foods, such as nuts or starchy seeds, thereby disrupting the trade networks.

A fourth and possibly interrelated reason is that intensified horticulture became so successful that increased agricultural production may have reduced variation in food resource availability between differing areas. This reliance on horticulture, involving only a few types of plants, would have carried with it a risk where variations in rainfall or climate could cause famine or shortages.

Rather than a prehistoric interaction sphere sharing earthen architecture memorialization of the dead and the exchange of high status goods of nonlocal materials, as existed in the Middle Woodland, the Late Woodland saw the rise of numerous small-scale cultures distinctive to particular geographical areas.

In the Carolinas, the Late Woodland (A.D. 600-1100) was a continuation of the Middle Woodland Deptford culture. Even sand burial mounds continued to be constructed. The Late Woodland period for this area is differentiated from the early Middle Woodland on the basis of the tempering and surface treatment of pottery styles.

The Late Woodland cultures in coastal North Carolina, such as the Colington (historic Carolina Algonkian) and Cashie (historic Carolina Tuscarora) phases, emerged about A.D. 800. These cultures continued essentially unchanged until ca. A.D. 1520, when contact with Europeans in the Carolinas occurred. Shell and grit-tempered pottery, horticulture (involving maize, squash, sunflowers, and beans), burial ossuaries, bow-and-arrow technology, palisaded villages, and seasonal settlement movement to supplement horticulture with hunting and gathering, typify these cultures. These cultures are present atFort Raleigh National Historic Site and possibly Cape Hatteras National Seashore.

The Late Woodland of the piedmont and western North Carolina (A.D. 600 - 1000) is presently not as well understood as either the previous Middle Woodland or the South Appalachian Mississippian culture that succeeded it. Likewise, the information on Late Woodland for much of South Carolina is so scant that some researchers have postulated a depopulation of the area for much of this period until replacement by the South Appalachian Mississippian culture.

In Georgia, Alabama, east Tennessee, and northern Florida, Late Woodland sites are identified by the occurrence of Swift Creek pottery styles through ca. A.D. 750. Gradually, this area evolved into the core area of the South Appalachian Mississippian culture by about A.D. 1000.

In northeast Florida, the St. Johns culture, discussed above in the Middle Woodland period, continued as the Timucuan culture up to contact with Europeans in the sixteenth century with few modifications in their material culture and subsistence base. Timucuan sites have been recognized in such parks as Timucuan Ecological And Historic Preserve, Fort Matanzas National Monument, Cumberland Island National Seashore, and Canaveral National Seashore. Similarly, the Calloosahatchee Region of southwest Florida, (ca. A.D. 700) saw the beginning of the Calusa culture at present-dayBig Cypress National Preserve andEverglades National Park. This cultural group subsisted to a large extent on maritime food resources, yet constructed large settlements and temple mounds. The Calusa culture continued as the dominant culture in south Florida through the sixteenth century.

The Weeden Island culture (A.D. 300-1000) developed locally in northwest Florida, probably out of the preceding Swift Creek culture, and spread throughout much of northern Florida and the panhandle of the Gulf Coast including areas now contained in Gulf Islands National Seashore. Weeden Island culture was characterized by the construction of burial mounds containing nonlocal burial goods, interred with the dead in imitation of Middle Woodland cultures. The subsistence strategies of the Weeden Island cultures were initially concerned with the seasonal collecting of wild plant foods and shellfish. However, by A.D. 800 in the interior coastal plain, maize horticulture appears to account for a good portion of the food supply, allowing for expansion of the territory and elaboration of political power.

As a display of this power, the Weeden Island culture undertook the construction of some of the earliest dated flat-topped platform (or temple) mounds (ca. A.D. 400). Apparently, these early mounds were intended to serve as bases for charnel houses for the dead as opposed to merely interment mounds for the elite of the Weeden Island culture. Eventually, evidence appears of multiple flat-topped mounds serving as a mortuary complex, with some mounds also serving as the base for a structure for the head of a clan or lineage. In this respect, the Weeden Island flat-topped temple or charnel house mounds may be considered proto-Mississippian models for more complex societies in the Southeast after ca. A.D. 1000. Influenced by the Weeden Island culture, cultures in Georgia, Tennessee, Alabama, and Mississippi also constructed flat-topped mounds during the Late Woodland period.

The lower Mississippi River Valley, consisting of eastern Arkansas, western Tennessee, Louisiana, and western Mississippi, saw the emergence of the Late Woodland Baytown culture (A.D. 300-700). The Baytown culture succeeded the Marksville culture of the Middle Woodland. Instead of major earthwork centers, the Baytown culture built dispersed settlements. Major innovations in the Baytown phase were the introduction of bow-and-arrow technology and horticulture.

In other areas of Louisiana and Arkansas arose the Late Woodland Troyville culture (A.D. 400-800). The Troyville people continued building ceremonial centers, like the earlier Marksville culture, but the mounds were civic or ceremonial temples, not burial mounds.

The Baytown and Troyville cultures of the lower Mississippi River Valley were followed by the Coles Creek culture in the latter part of the Late Woodland period (A.D. 700-1000). The Coles Creek culture area covered the entire lower Mississippi River Valley and showed considerable cultural homogeneity by an increased concern with socio-religious authority exemplified by the construction of temple mound complexes surrounding open plazas. Location of these sites on major waterways seemed to reflect a renewed interest in interregional associations of the previous Middle Woodland period.

In central Mississippi, the Miller culture continued into the Late Woodland, but by A.D. 400 there is a cessation of burial mound construction. After A.D. 600, there is evidence of maize horticulture and bow-and-arrow technology. About A.D. 1000, the Miller culture area becomes incorporated into the succeeding Mississippianculture.

In Tennessee and Kentucky, some accretional burial mounds were still being constructed in the Late Woodland, but construction of earthwork enclosures ceased. Large projectile point types gave way to smaller forms indicative of bow-and-arrow use. Ceramics were similar to Middle Woodland but without the Hopewellian decorative motifs.

For further information, visit:

- Florida Historical Contexts

- "Virginia's Indians, Past & Present," Internet School Library Media Center

- State map of North Carolina with general location of selected sites including several Woodland period coastal sites

- Cultural periods represented in Tennessee