Insomnia, A Fascinating Enemy (original) (raw)

GENEVA — When it comes to insomnia, some use the megaphone of the digital era, posting Facebook status updates to round up companions of misfortune — one-night or lifelong problem sleepers who want to talk. But there are myriad other coping mechanisms for this growing societal issue. And though insomnia can mean pure agony, it also inspires a kind of fascination.

“There’s the nightmarish aspect the following day, but it’s also some sort of a special moment,” says Kate, co-director of the Black Movie Festival. “Everyone around me is asleep. I feel as if I’m secluded from the whole world.”

Sometimes insomnia can even be productive. “During the time when I don’t sleep, I imagine solutions to problems,” Kate says. “Finding these solutions and writing them down gives me a sense of relief. But the following day, when I read them again, they often seem crazy. There may be a productive side, but it appears afterwards. There seems to be underground activity going on during these nights.”

Secretary and dance therapist Catherine feels a real ambivalence about the nights when she has difficulty sleeping. “They can be unbearable, but there’s also something I like about them,” she says. “I become inspired, have personal revelations, things I had never thought about.”

Awakening dreams

Rocco, a journalist from the Tribune de Genève, admits he has trouble going to bed and accepting that the day is over. “It can be appealing, yes. In the silence of the night, with everything becoming calm around, you feel almost privileged,” he says. “There’s a nostalgic side, linked to my post-adolescence: a period during which I prompted the insomnia, I refused to go to sleep, I spent my nights reading. But the romantic aspect of insomnia fades away after a few years. You know you will pay the consequences the next day. Now, when it happens to me, it’s quite discouraging.”

American novelist Kenneth Calhoun has imagined an insomnia epidemic. In his remarkable book Black Moon, published in March, no one sleeps anymore. The causes are unknown and the consequences apocalyptic. Mankind wanders around in a state of insomniac confusion, where memories are fading away. There are still a few sleepers, and no one knows why. Their sleep causes fits of deadly rage in those who do not sleep.

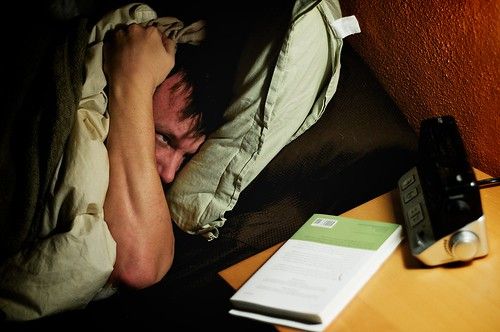

Photo: bark

“This idea is an exaggeration of a situation I lived taken very far,” the author explains by phone. “My partner couldn’t sleep while I slept perfectly. Just for fun, we acted as though there was a kind of resentment. In the wake of these jokes, I started asking myself: What if this became pure anger?”

Oliviane, an art historian, says she finds it incredibly annoying when someone falls asleep quickly. “I’ve been awakened by the sound of a hamster running on a carpet in another room,” she says, adding that she doesn’t really enjoy sleeping. “I tend to be in control a lot, so I don’t like situations where I can’t control anything.” Still, getting some rest seems to be a little easier with earplugs on. “I’ve accepted the presence of this foreign body in my little bubble,” she says. “It’s a way of letting go.”

Thierry, a librarian and musician, characterizes his sleeping troubles as chronic, and he’s been under the care of a physician for more than a decade. “Sleep analysis — polysomnography — detected the reason why I wake up at night: dreams,” he says. “Not necessarily nightmares, but mostly extremely realistic dreams, like ultra-high-definition films.”

Random fact: For the Romans, the term “insomnia” was initially used to describe the condition of having disturbing dreams.

The war on sleep

In Insomnia: A Cultural History (Reaktion Books, 2008), New Zealander Eluned Summers-Bremner traces the first references to the problem to the Epic of Gilgamesh tablets. Ancient Greeks believed insomnia was caused by obsessive love. This was the case for Dido and Medea — and later, in Hindu mythology, Radha, who couldn’t sleep when she imagined Krishna sleeping with another girl.

In the Middle Ages, it was customary to sleep in two distinct stages, waking up around midnight for one or two hours of a socially established insomnia before returning to what was called the “second sleep.”

With every era bringing new sources of anxiety, insomnia has become more common over the years. Of course, in the 18th century, industrial society effectively declared a war on sleep. That’s when the idea of political leaders and top managers barely sleeping yet still functioning at a high level settled in. “There is really no reason why men should go to bed at all,” Thomas Edison said in 1914. He spread his ideal of a sleepless world by posing for the press with assistants gathered in an “Insomnia Squad.”*

Meanwhile, regular people these days try to sleep by finding techniques that have varying results. “I picture a speck of light in the dark, and I get closer to it,” Kate says. For Thierry, eating yogurt tends to help, as does reading. “It has to be as boring as possible,” he says of his reading material. “Philosophy books on time, death, religion or essays in foreign languages.”

Faustine, an artist, says she suffers from insomnia when she’s working intensely on a project and has lots of creative energy. Sometimes, if she’s not working the next day, she’ll smoke a joint to help get to sleep. “And I drink warm water,” she says.

So is insomnia an individual disorder or a civilizational pandemic? A frightening void or the result of unmanageable overflow of tasks? “Both,” it seems, is the answer to these questions. Eluned Summers-Bremner writes that in contemporary cities, which are like “laboratories of insomnia,” a sort of invisible community appears. Insomniacs of the world, unite!

* Dangerously Sleepy: Overworked Americans and the Cult of Manly Wakefulness, Alan Derickson, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013.