Refuting the Vieto-Katuic Hypothesis: Reconsidering Ethnohistorical Linguistic Scenarios (original) (raw)

2024, Austroasiatic Linguistics In honour of Gérard Diffloth (1939-2023)

Abstract

Diffloth (1991b) first proposed this grouping (what he called “Proto-Katuic-Vietic”) primarily based on phonological evidence, while also positing that vocabulary was shared by Vietic and Katuic, though he did not provide supporting lexical data. Later, the current author (Alves 2005) proposed a few dozen lexical isoglosses shared by Vietic and Katuic. Other scholars accepted the Vieto-Katuic hypothesis in historical linguistics publications, as to be discussed in Section 2, and it has been tied to speculation about early migrations of ancestors of the Vietnamese. The hypothesis has even been noted in a chapter on prehistory in Vietnam in an English-language historical text (Kiernan’s 2017 “Việt Nam: A History of the Earliest Times to the Present”), with the idea that this early group migrated northward from the Annamite Cordillera in north-central Vietnam and bordering parts of Laos. However, (a) the historical phonological data seemed persuasive but is minimal, (b) the lexical data was more limited than that available today and was gathered through paper texts, not digital tools effective for sifting data, and (c) no archaeological evidence was presented or indeed available to support Diffloth’s assertion. In view of current available data—much more than just 20 years ago—with an overview of the phonological, morphological, lexical, and ethnohistorical aspects and weighing the evidence, the Vieto-Katuic hypothesis can no longer be considered valid. The goal of this article is not only to demonstrate how current data and methods show that the Vieto-Katuic hypothesis does not hold water. It is also aimed at pointing out that archaeological evidence strongly suggests a north-to-south movement of Austroasiatic speakers into Mainland Southeast Asia (MSEA hereafter), and that the result of this event significantly complicates claims of a south to north migration of early Vietic peoples, or a homeland near central Vietnam, a claim lacking archaeological support. Also, the linguistic evidence shows that Katuic and Vietic are distinct branches within Austroasiatic and that they share features likely due to language contact with each other at various times over history, and not necessarily with substantial time depth.

Figures (7)

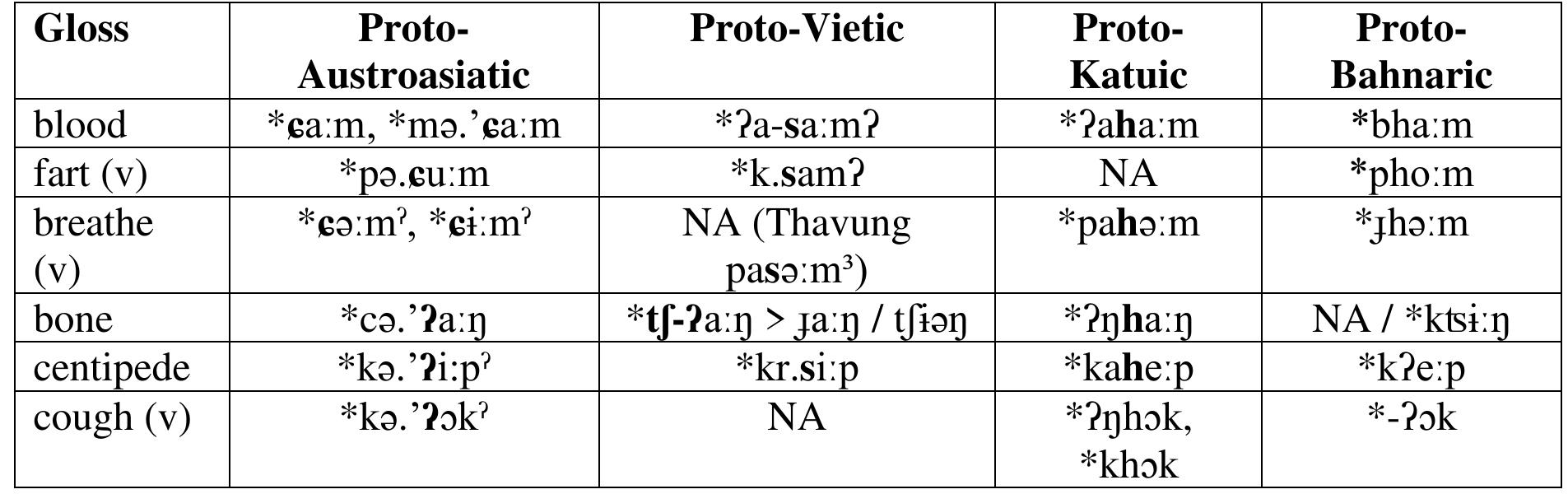

Table 1: Proto-Austroasiatic *¢ and *? and reflexes in Proto-Vietic and Proto-Katuic In contrast to this lack of shared phonological innovation, in recent exploration of Proto-Austroasiatic rime glottalization,” Gehrmann (2021) shows that Vietic rime glottalization patterns with the Mangic and Pakanic languages spoken in northern Vietnam and parts of southern China, as in Table 2. While Katuic exhibits what Gehrmann terms a “deglottalized pattern”, along with branches such as Bahnaric, Khmeric, Munda, Khasian, and others, Vietic and the languages Mang, Bugan, and Bolyu constitute a “northeastern pattern” with a four-way distinction that developed from the original two-way distinction in Proto-Austroasiatic. Sidwell has been skeptical of this proposal (Sidwell 2005b: 196), and more recently (Sidwell 2015: 176), he questions this situation in terms of the naturalness and conditioning factors of the change. Also, we can consider Sidwell’s recent (2024) reconstructions of Proto-Austroasiatic, based on a thorough re-assessment of comparative data (see Sidwell & Alves (2023) for a summary). These reconstructions show that what Diffloth reconstructed as a glottal stop in Proto-Austroasiatic was instead two distinct sounds, namely, *? and *¢, as shown in Table 1. If Sidwell’s reconstructions are valid, then Proto-Vietic *s and Proto-Katuic *h are from *¢ (‘blood’, ‘fart (v)’, and ‘breathe (v)’”), what can be considered natural change from a typologically less common fricative sound to more common ones. Note that Proto-Bahnaric, like Proto-Katuic, has *h. In the other instances (‘bone’, ‘centipede’, and ‘cough (v)’) with a glottal stop, there is no shared pattern in Vietic and Katuic.

Table 3: Isoglosses for Proto-Vietic and Proto-Katuic®

Further confounding the situation is that, as I found in sifting the lexical data, four items are shared by only Vietic and Bahnaric (albeit also including some sub-branch reconstructions), as in Table 4. The number of words shared by Vietic and Bahnaric is smaller than by Vietic and Katuic, but assuming relative stability over time, neighboring branches are likely to share a larger number of words than non-adjacent ones. Sidwell (2021: 199) has noted high lexicostatistical numbers connecting Bahnaric and Katuic. Regardless, two branches of Austroasiatic can share isoglosses but not belong to a higher phylogenetic node, and borrowing in an early period must be considered one likely reason for the shared words.

Table 5: Reconstructed numeral terms among Austroasiatic branches Finally, a number of words are attested in Vietic, Katuic, Bahnaric, and sometimes othet nearby language groups, such as Khmer and Khmuic, as in Table 6. While these coulc hypothetically be retentions from Proto-Austroasiatic, such a situation is not demonstrable or refutable. Instead, in cases of shared forms in neighboring communities, they more likely represent innovations in one branch that spread by contact to others in this geographically contained region of north to central Vietnam. This further highlights the results of long-term language contact among the branches, such that words for ‘bear,’ !> ‘thunder,’ ‘forest,’ basic verbs, and other noncultural words can be and have been shared among the branches.

Proposed phonological correspondences for a Vieto-Katuic group are no longer valid, and the shared vocabulary is not enough to support phylogenetic status. Furthermore, the data shows significant long-term contact among the branches in this region, such that the shared proto-branch forms in Vietic and Katuic can be considered the result of ancient language contact.

Table 7: Proto-Vietic reconstructions with an *?a- presyllable However, other than this small number of items, no other Proto-Vietic reconstructions for animals have this presyllable. In contrast, in Proto-Katuic (Sidwell 2005a), 32 reconstructions for animal terms have an *?a- presyllable, and another 10 proto-forms have a nasal presyllable *2N-. If Proto-Vietic had this word-formation strategy, we should expect more than a few shared forms. Also, if the word for ‘elephant’ is a Tai loanword, it should date to the 2nd millennium CE, and the [?a-] presyllable must have been added then: this raises the possibility that these words with the [?a-] presyllable were borrowed at some time in the last several centuries. Finally, were these presyllables in Proto-Vietic, the onsets in Vietnamese should have lenited to voiced fricatives, such as intervocalic *k to modern Vietnamese ‘g’ [y], but they have not (see Alves 2024 for an overview). This situation shows evidence of a few lexical borrowings, not retention of a proto-language word- formation strategy. A. ff... ..... _. 44-44. . JA. yg. kL 2 ml rl a (

Key takeaways

AI

- The Vieto-Katuic hypothesis is invalidated by a lack of substantial phonological, lexical, and archaeological evidence.

- Current data indicates a north-to-south migration of Austroasiatic speakers into Mainland Southeast Asia.

- Only 14 isoglosses are now identified between Proto-Vietic and Proto-Katuic, significantly fewer than previous claims.

- Shared features between Katuic and Vietic likely result from recent language contact rather than common ancestry.

- Archaeological findings contradict claims of a south-to-north migration of early Vietic peoples in Vietnam.

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

![Table 7: Proto-Vietic reconstructions with an *?a- presyllable However, other than this small number of items, no other Proto-Vietic reconstructions for animals have this presyllable. In contrast, in Proto-Katuic (Sidwell 2005a), 32 reconstructions for animal terms have an *?a- presyllable, and another 10 proto-forms have a nasal presyllable *2N-. If Proto-Vietic had this word-formation strategy, we should expect more than a few shared forms. Also, if the word for ‘elephant’ is a Tai loanword, it should date to the 2nd millennium CE, and the [?a-] presyllable must have been added then: this raises the possibility that these words with the [?a-] presyllable were borrowed at some time in the last several centuries. Finally, were these presyllables in Proto-Vietic, the onsets in Vietnamese should have lenited to voiced fricatives, such as intervocalic *k to modern Vietnamese ‘g’ [y], but they have not (see Alves 2024 for an overview). This situation shows evidence of a few lexical borrowings, not retention of a proto-language word- formation strategy. A. ff... ..... _. 44-44. . JA. yg. kL 2 ml rl a (](https://figures.academia-assets.com/119282868/table_007.jpg) ](

](