The Occupation of Baker's Flat: A Study of Irishness and Power in Nineteenth Century South Australia (original) (raw)

Abstract

This thesis was submitted in partial requirements for the degree of Master of Archaeology, Department of Archaeology, Flinders University, October 2014. This research investigates Irish social identity (‘Irishness’) in the nineteenth century, centring on a substantial and long-lived Irish settlement known as Baker’s Flat, in the mid-north of South Australia. The research questions focus on the concepts of identity and power, specifically, how these Irish expressed their identity through material culture, and what this tells us about the community and its power relations. The occupation of Baker’s Flat began in 1854, when many Irish families came to labour at the nearby Kapunda copper mine, and squatted rent-free on the Baker’s Flat land. The settlement persisted until at least the 1920s, set apart from the broader community. Although hundreds of Irish people lived there, the written histories document little about the community, and if mentioned at all, the narrative tends to be a stereotypical one based on the widespread perception of the Irish as dirty, wild, drunken and lawless. In large part this negative narrative was probably stimulated by the refusal of the residents to pay rent or allow outsiders into the community, and their resistance to the landowners’ attempts to remove them. Analysis of a metal artefact collection and site survey have enabled a more complex interpretation of Baker’s Flat, with Irishness evident through several material realms. Many of the artefacts conform to general Victorian trends, and align with a people endeavouring to conform to the ideal of respectability. Catholicism, a key marker of Irishness, is evident through artefactual and historical evidence, and appears as both a cultural way of life and a spiritual belief system. The Catholic Church’s tolerance for folk practices may have allowed a folk tradition practice to continue here alongside traditional religious practice, as it did elsewhere. At a site-wide scale, the Irishness of this community is expressed through the spatial layout of the settlement, and historical evidence of the lack of fencing and unrestrained stock, all of which indicate the continuation of a traditional Irish ‘clachan’ and ‘rundale’ settlement pattern constructed around clustered kin-linked housing and communal farming methods. This resulted in a close-knit community based around mutual obligation which enabled this group to stand united against the dominant power of the landowners through an extended court case.

Figures (103)

Figure 1.1 Location map showing the Baker’s Flat study area outlined in red, and locations of Kapunda and Adelaide. Image from Google Earth, 27 J uly 2014.

Figure 2.1 Identity is a complex mix of elements. the lenses of class and ethnicity. elements are all factors in its social identity, which will be explored further through The significance of class in western capitalist society owes much to the work of

Figure 2.2 Irish symbols used in a circular brooch, sugar bowl and tongs, and casket, dating from the 1850s to 1890s (Sheehy 1977:230-231). and art (Sheehy 1977). Figure 2.2 illustrates some of these symbols. Middle A ges, including high crosses, circular brooches and interlace designs, all

Figure 2.3 Typical examples of Irish vernacular architecture (Danaher 1978:18, 30, 31). Two historical studies have noted similarities between traditional Irish settlement

Michael, had pre-deceased her in 1918 and 1934 respectively, both at Baker's Flat Baker's Flat (Chronicle 1945:17; Hazel 1975). Her mother, Mary, and brother,

Figure 3.5 The Lonely Cottage. Photo by J ohn Kauffmann of a cottage at Baker’s Flat, exhibited at the 1907 Annual Exhibition of the Royal Photographic Society of Great Britain (Art Gallery of South Australia n.d.).

Figure 3.4 Nineteenth century cottage on Baker's Flat, date unknown. Photo courtesy of P. Swann, Kapunda.

Figure 3.6 An old time village, Baker’s Flat, near Kapunda. Photos by J ohn Kauffmann, published in the Christmas Observer of 13 December 1906. Photo courtesy of the Kapunda Museum.

Figure 4.1 Sketch map, not to scale, showing the locations of dwellings on Baker's Flat.

COORDINATES FOR TRANSECT SURVEY ON BAKER’S FLAT, 14 FEBRUARY 2013

Figure 4.2 Transects completed during the field survey, site boundary outlined in red. Image from Google Earth 27 April 2014. Table 4.1 Transect coordinates completed during Baker’ s Flat field survey.

were catalogued. Artefacts were cleaned using a dry brush to remove just enough surface dirt to reveal clock components (Table 4.2). This left a total of 1,099 metal artefacts, all of which

Figure 5.4 'Dance floor’, an area of compacted ground, looking south-east.

which have been used as broad headings to structure the results (Figure 5.5).

Figure 5.7 L to R: #0918 possible door knocker; #0927 cupboard door plate. well as two brass and iron alloy cupboard door knobs.

and covers, door hardware, hinges and lengths of metal pipe or wire (Figure 5.6). They include a solid brass horse’s hoof terminating in a hollow finial, possibly part

Figure 5.9 L to R: #0118, pepper cellar lid; #0191, sugar caster lid with stylised leaf pattern; #0911, lion’s paw, possibly serving tray leg. nineteenth century.

Figure 5.8 Domestic artefacts (n=91) by type. Containers

Figure 5.10 #0213, knife handle, symmetrical design. (Figure 5.10). Itis notable that this is the only knife in the collection. Flatware

Figure 5.11 Flatware (n=62) by type. forks, 38 full or partial spoons, and 18 fragments that could be either forks or spoons.

to the twentieth century (Godden Mackay Heritage Consultants 1999a:414).

Figure 5.13 Flatware dated by maker. from 1864 to the 1890s (Figure 5.13). this collection can be refined, based on their makers’ marks, to start times ranging

Figure 5.18 Buckles (n=40) by type. (n=9), snake (n=6), or sporting (n=13) (Figure 5.18).

Figure 5.17 Personal artefacts (n=700) by type. which are buttons (n=548, 78.3%) (Figure 5.17).

is engraved with the Christian symbols of a botonee cross and vines (Figure 5.19). Plain buckles and also of the Christian doctrine of the Holy Trinity (Figure 5.19). Another buckle

Figure 5.20 Snake buckles. L to R: #0332; #0335. Sporting buckles Thirteen buckles have sporting motifs. One is associated with lacrosse, the remainder

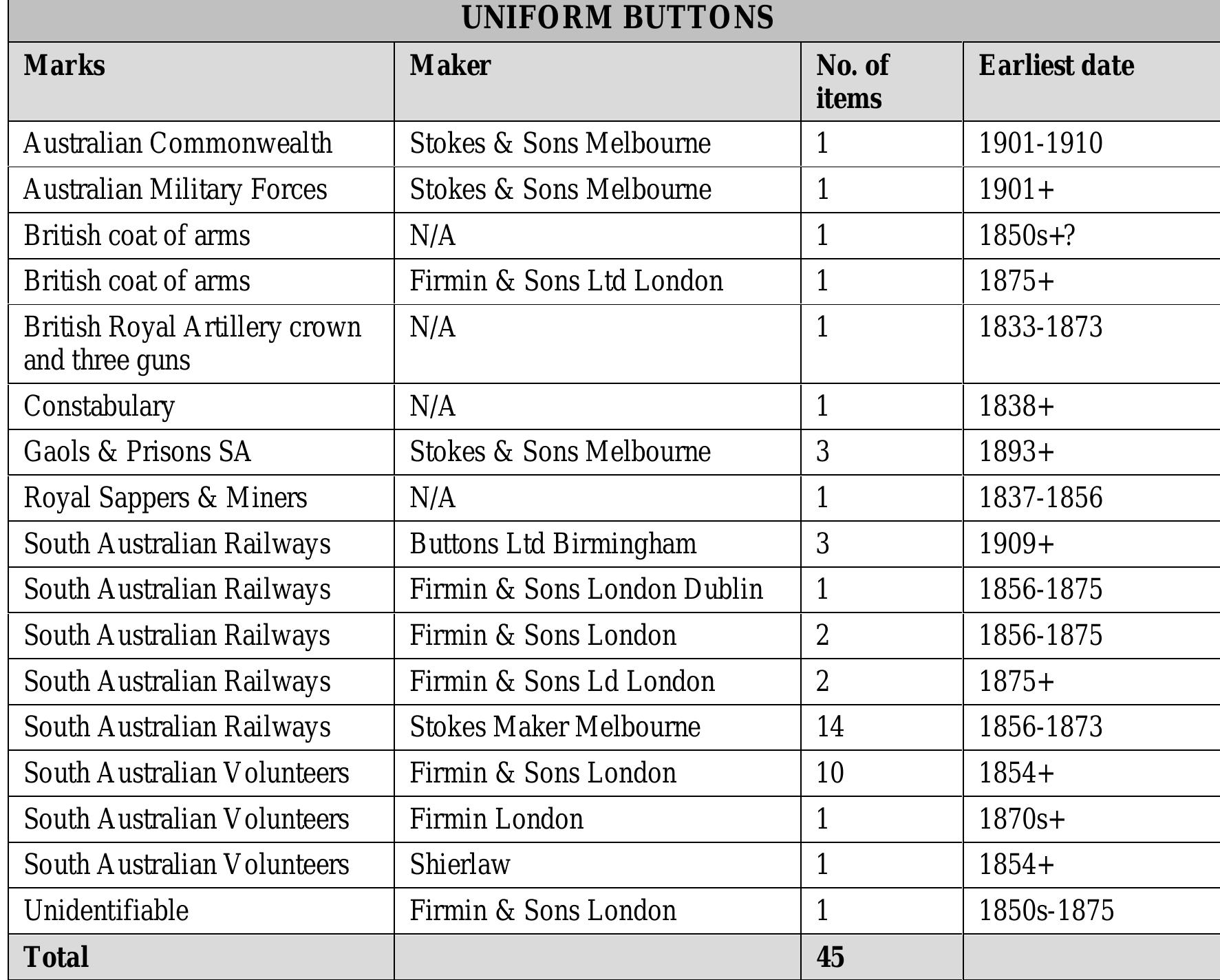

The 548 metal buttons fall into several styles, as shown in Figure 5.23. The categories with the fewest numbers are bachelor buttons (n=4), blazer buttons

Meredith 2012:11, 15, 20; Peacock 2010:8). 1880s to 1910, representing the peak of decorative button manufacture (Meredith and

(Figure 5.34) and chain (Figure 5.36) in the collection.

Figure 5.26 Buttons resembling cut steel. L to R: #0785, stylised flower; #0786, stylised sunburst. Trouser buttons

Figure 5.27 #0443, four trouser buttons made by C.H. Shakeshaft of Kapunda. known to be living in Kapunda from 1884 (Kapunda Herald 1926:2; Rootsweb records of the Ennistymon Union in 1848 list ‘John Kerin Ennis’ as tendering for the

(n=48, 51.6%). There are no earrings. Jewellery in the Victorian era was characterised by transient trends. Naturalistic There are 93 pieces of jewellery (Figure 5.30), more than half of which are brooche

fashions, and dating from at least the 1840s (Benjamin 2003:52; Hinks 1975:43).

popular in the 1880s and 1890s as a good luck symbol (Hinks 1975:74). the horseshoe motif, which, as well as being associated with hunting, was also

buttons in Figure 5.26 and a chain shown in Figure 5.36.

retum to happiness, friendship and fidelity (Phillips 2008:78). Chains and bracelets from its hallmark to 1892; its motifs of lily of the valley and ivy are symbolic of a There are four partial chains, two bracelet fragments, and a heart-shaped padlock that

Figure 5.36 #0913, large diamond-shaped chain, with flower pattern, 260mm in length. Cufflinks, hat pins and pins

Figure 5.37 Cufflinks. L to R: #0901, copper alloy West’s solitaire cufflink; #0893 silver cufflink; #0894 rolled gold cufflink; all with naturalistic designs of flowers and fern frond: ) 1850s (O’ Day 1982:10; Phillips 2008:78). Figure 5.37 shows three examples.

Figure 5.38 L to R: #0197, hat pin in the shape of a golf club; #0872, copper alloy stick-pin with rose motif.

featuring Queen Victoria and the date 1863 (Figure 5.39).

engraved with stylised flowers and leaves (Figure 5.40). Other costume items silver band shaped as a belt and buckle, and a very wom gold wedding band

A copper alloy money clip (Figure 5.42) is stamped with a design number 234422,

registered in 1881 (The National Archives 2014).

Figure 5.43 Toy horses. L to R: #0907, tin alloy horse on stand; #0193, lead alloy racehorse. remaining toys represent a lamb, a propeller and a possible horse. The single gaming token depicts the young Queen Victoria on one side, and the

Figure 5.44 #0216, front and back of copper alloy gaming token. Societal/religious

Figure 5.45 Societal/religious items (n=275) by type. money, registration tags and religious objects (Figure 5.45)

jubilee in 1897, and a bronze medal with an image of the veiled Victoria and the

There are 122 identifiable English coins, the earliest of which are two sixpences

Five coins, all low-value ‘copper’ coins, have been pierced (Figure 5.48) or part

pierced (Figure 5.49): two farthings, two half pennies, and a Chinese coin.

appears from the shape and weight to be a post-1860 penny.

Examples of three other modified coins are shown in Figure 5.50. These are a

Table 5.2 Dog registration tags per year from 1885 to 1936. NUMBER OF DOG TAGS PER REGISTRATION YEAR The South Australian Dog Act of 1884 established the dog tag system. Each year, the

Figure 5.51 Dog tag examples, all from district 78. L to R: 1885-1886; 1887-1888; 1891-1892. district of the registered dog (Ransom 2005:22-23) (Figure 5.51).

Figure 5.52 Number of dog tags from specific councils. female tags were distinguished from male tags by a second hole at the bottom

With regard to rosaries, there are seven rosary crucifixes, two rosary medals and a with rosaries, 14 devotional medals, three Confirmation medals and two crosses case for a miniature set of rosary beads (examples in Figure 5.54). The two rosary A total of 29 religious items feature in the collection. There are ten objects associated

1832, and more than 12 million were said to have circulated around the world by

Figure 5.56 #0890, possible cockatoo chain, made of nickel alloy.

linch pin, and two unknown items.

Figure 5.57 #0109, two views of unknown object associated with G. May of Kapunda. G. May owned a saddlery business in Kapunda (South Australian Register 1876a)

Table 6.1 Instances of pierced coins or tokens in Australian archaeological reports. bones, bottles, clay pots, metal objects such as knives and horseshoes, pins and

Listed below are 104 family names, or variations thereof, associated with Baker’s Flat. Names are sourced from local histories, newspaper reports, family historians at Genealogy SA, church and state records.

THE O’CALLAHANS - LAST FAMILY ON BAKER’S FLAT?

Campbelltown: Neil Ransom, pp.50-53. Taken from Ransom, N. 2005 Collared: A History of Dog Registration in South Australia.

PAYMENT OF RATES FOR SECTION 7598, DISTRICT COUNCIL OF KAPUNDA

PAY MENT OF RATES, SECTION 7598, DISTRICT COUNCIL OF BELVIDERE

The information in the table below, which details the known owners of the Baker’s Flat land, is sourced from records of the South Australian Land Titles Office, the Forster et al v. Fisher 1892 court records, papers associated with the Ngaiawang Folk Province held in the archives of the South Australian Museum, the Kapunda Herald, and personal communications with Simon O’Reilley, Kapunda.

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.