TIME-WEIGHTED VS CONVENTIONAL QUANTIFICATION OF 24 HOUR AVERAGE AMBULATORY SYSTOLIC BLOOD PRESSURE (original) (raw)

Abstract

Background Conventional calculation of mean 24-h ambulatory blood pressure (BP), SBP and DBP based on the average of all BP readings disregards the fact that a larger number of measurements is usually scheduled during the daytime than at night, an imbalance possibly leading to an overestimation of 24-h average BP. The aim of our study was to quantify this possible bias and to explore its determinants.

Figures (9)

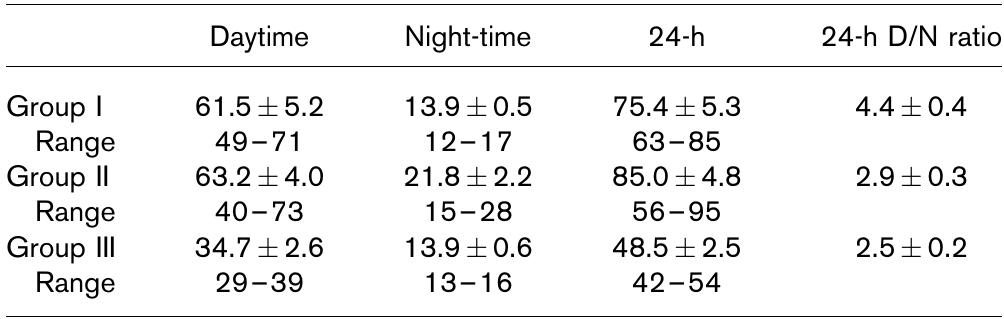

Table 1 Number of blood pressure readings for the daytime, the night-time and the 24-h period, and the day/night ratio of such numbers Values are expressed as mean+ SD, with the addition of the range betweer maximum and minimum number of readings for each of the three groups con sidered in our study. 24-h D/N ratio, ratio between 24-h daytime and night-time measurements.

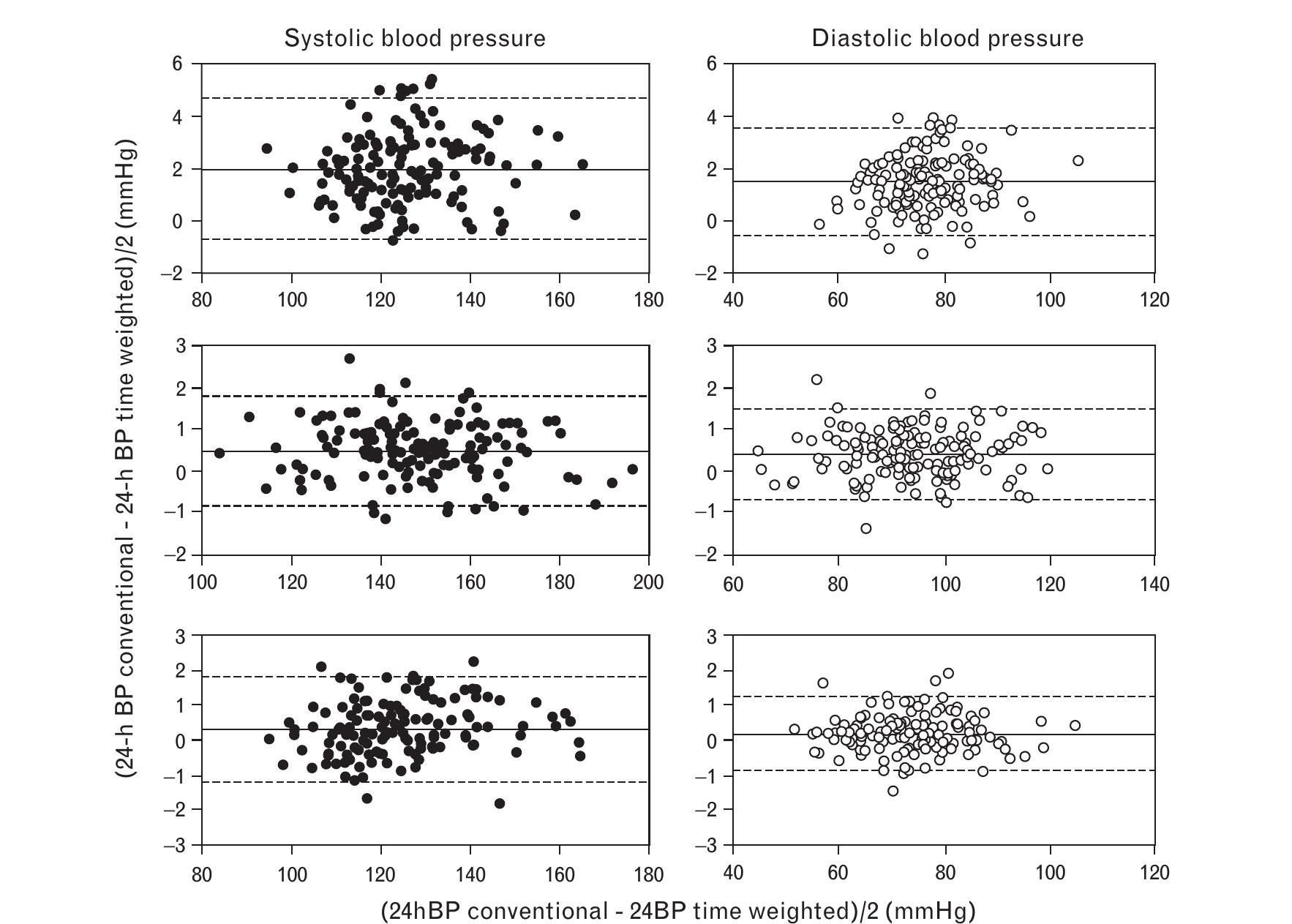

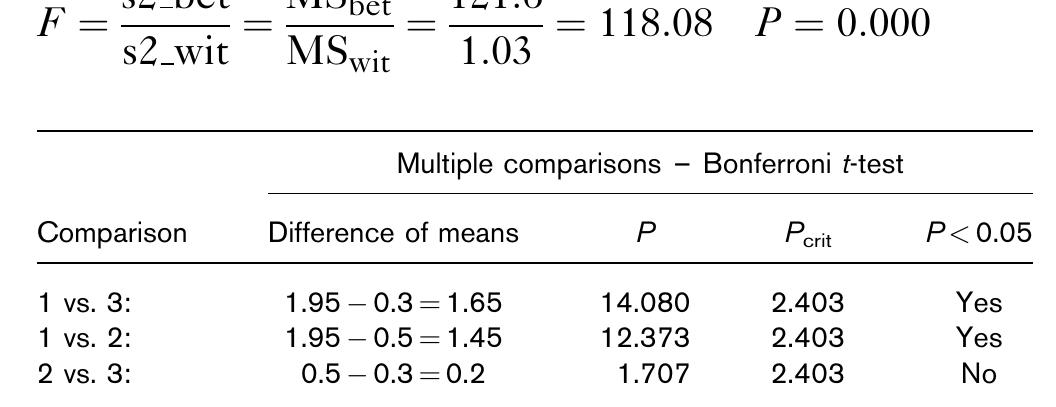

Bland-Altman analysis of the differences between 24-h blood pressures obtained by conventional and time-weighted analysis. Top panels: group |; intermediate panels: group II; bottom panels: group Ill. Left panels and black circles: 24-h SBP. Right panels and white circles: 24-h DBP. Solid line in each panel: mean value of overestimation bias. Dotted lines: 2SD over and under mean. BP, blood pressure.

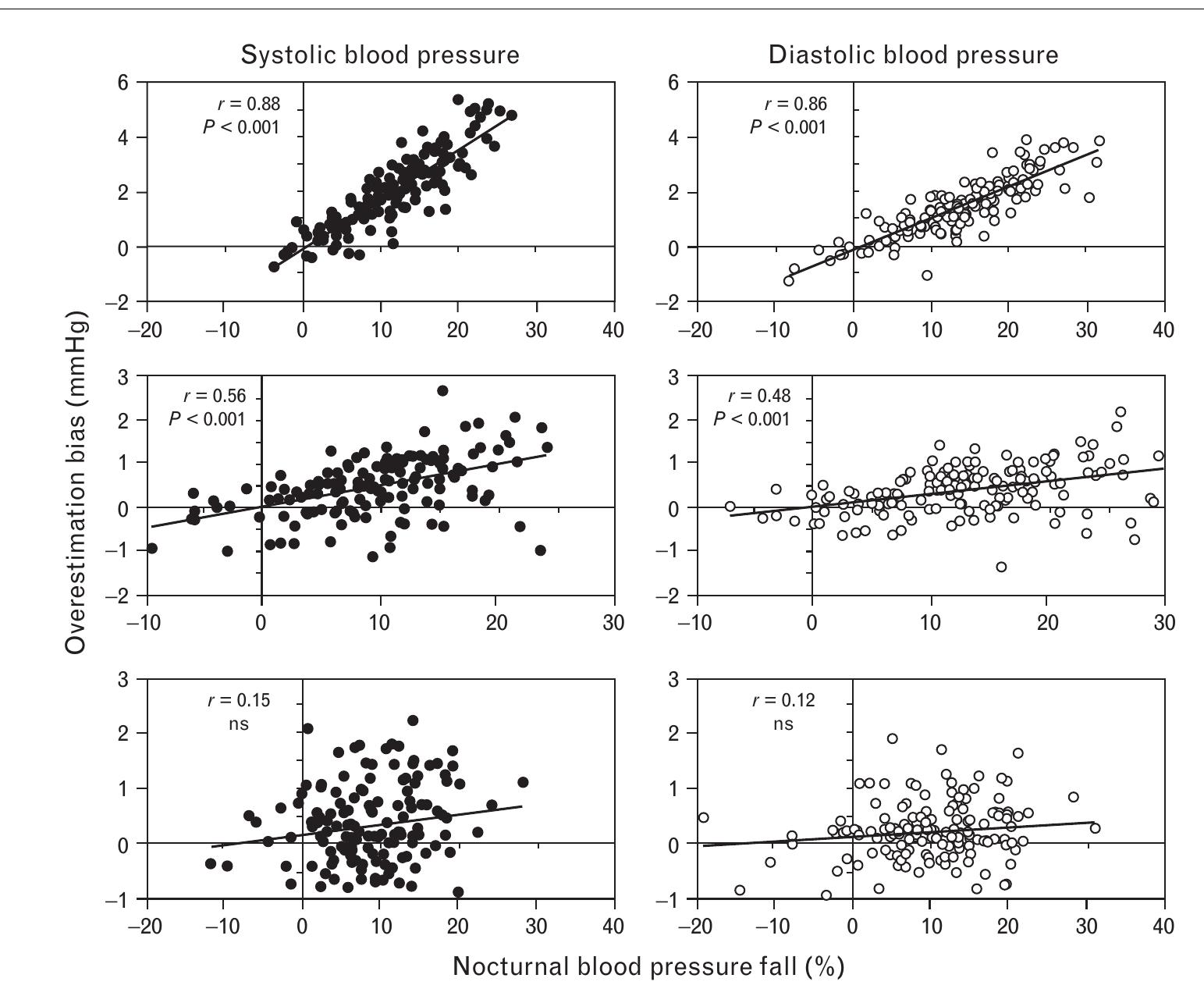

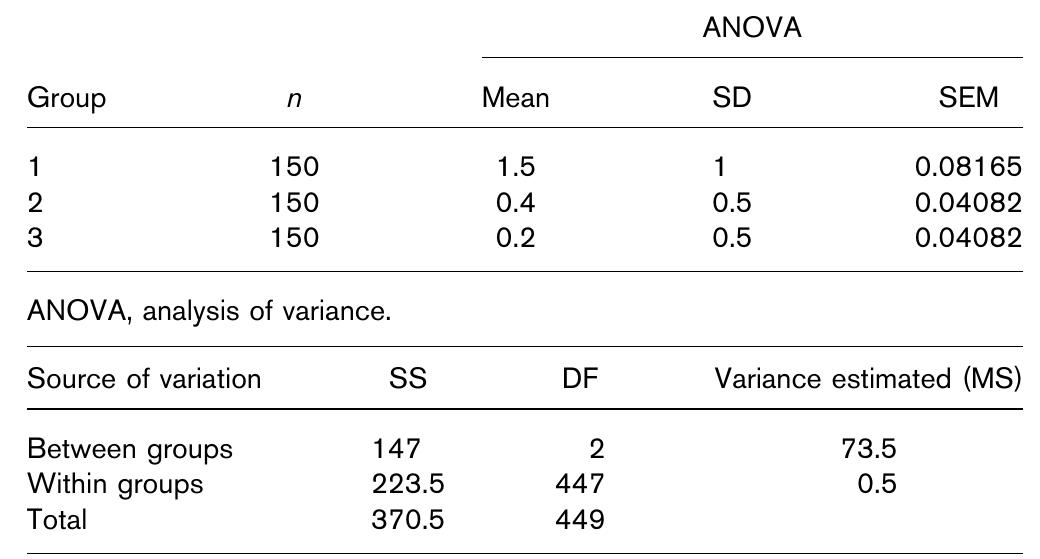

Correlation between nocturnal dip and calculated ‘bias’. Superior panels: group |; intermediate panels: group Il; lower panels: group Ill. Left panels and black circles: 24-h SBP. Right panels and white circles: 24-h DBP. Inserts in each panel: correlation coefficients and their statistical significance. NS, not significant.

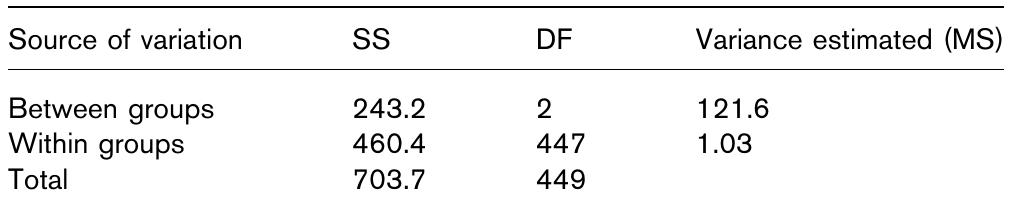

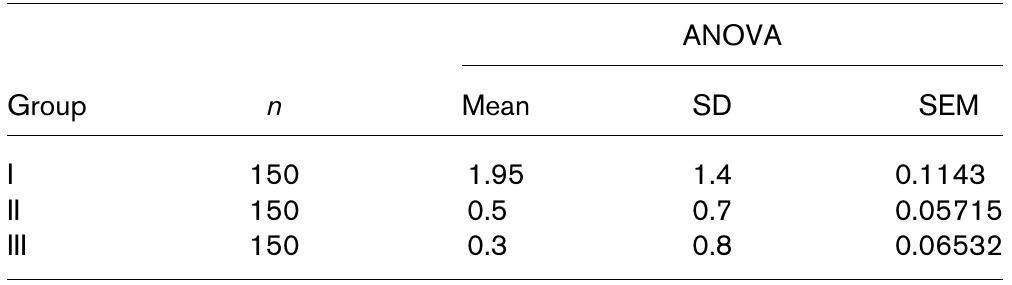

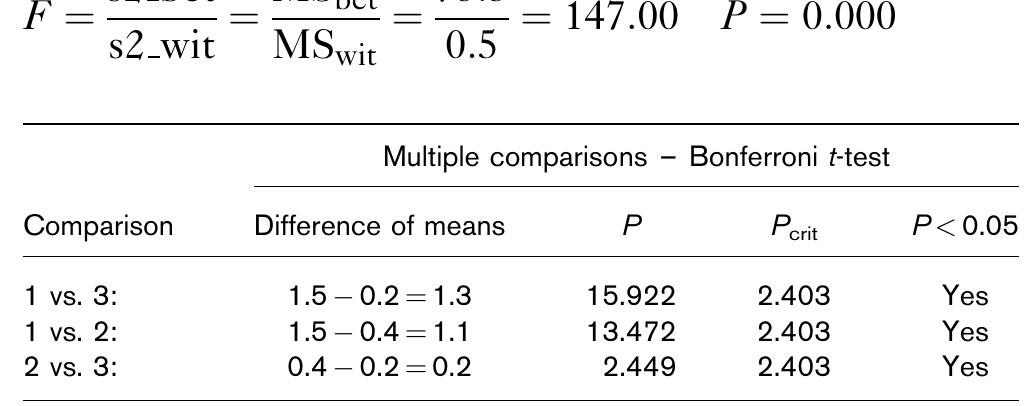

DF, degree of freedom; MS, Mean Square; SS, Sum of Squares. ANOVA, analysis of variance.

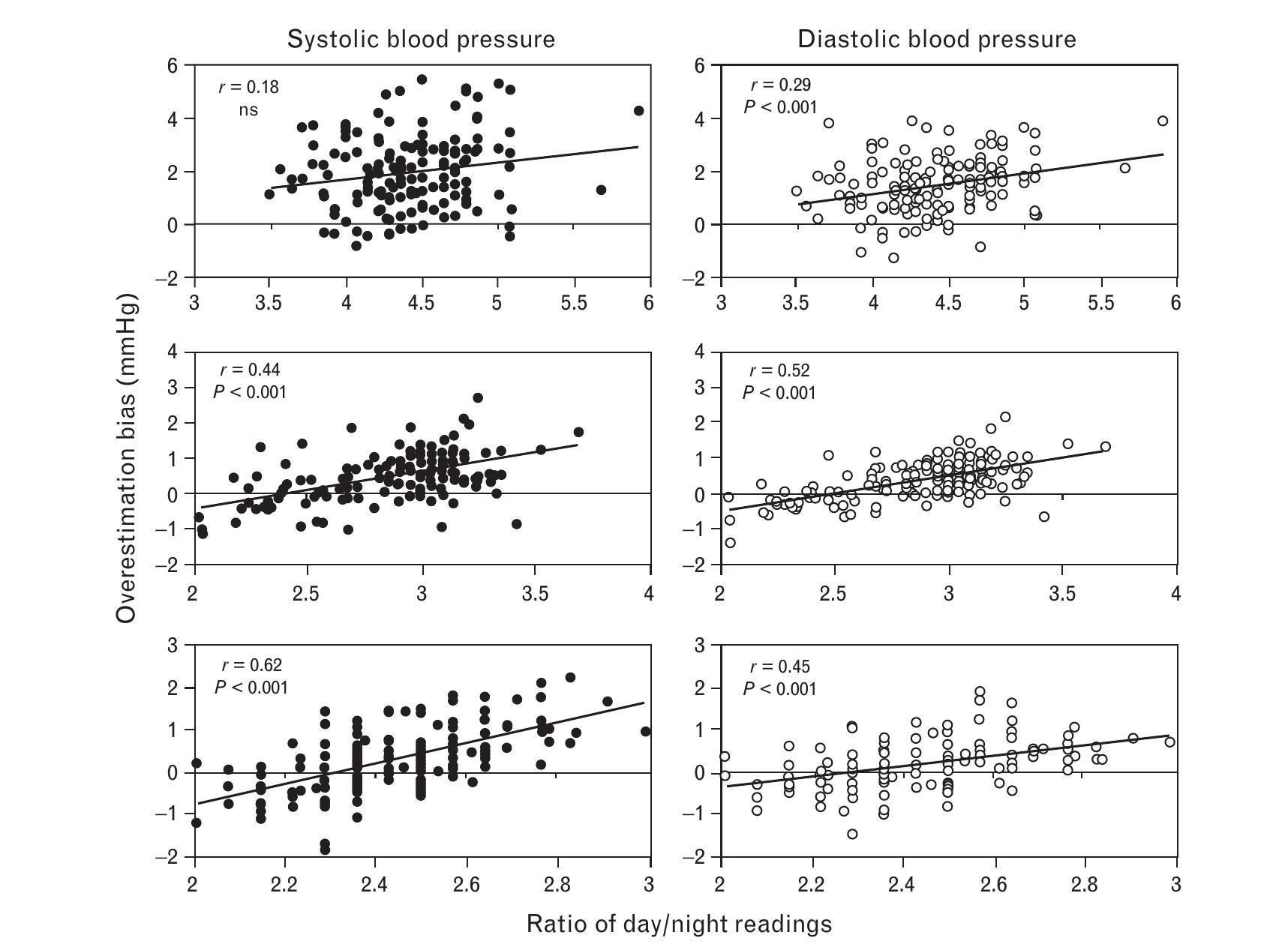

Correlations between total day/night ratio in number of readings and calculated ‘bias’. Superior panels: group |; intermediate panels: group Il; lower panels: group Ill. Left panels and black circles: 24-h SBP. Right panels and white circles: 24-h DBP. Insertions in each panel: correlation coefficients and their statistical significance. NS, not significant.

Degrees of freedom 447. Overestimation bias: SBP Addendum

Overestimation bias: DBP

Degrees of freedom 447.

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

References (21)

- Mancia G, De Backer G, Dominiczak A, Cifkova R, Fagard R, Germano G, et al. 2007 guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. The Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). J Hypertens 2007; 25:1105-1187.

- Pickering T, O'Brien E, O'Malley K. Second international consensus meeting on twenty-four-hour ambulatory blood pressure measurement: consensus and conclusions. J Hypertens 1991; 9 (Suppl 8):S2-S6.

- Verdecchia P, Porcellati C, Schillaci G, Borgioni C, Ciucci A, Battistelli M, et al. Ambulatory blood pressure. An independent predictor of prognosis in essential hypertension. Hypertension 1994; 24:793-801.

- Staessen J, Thijs L, Fagard R, O'Brien E, Clement D, de Leeuw P, et al., for the Systolic Hypertension in Europe Trial Investigators. Predicting cardiovascular risk using conventional vs ambulatory blood pressure in older patients with systolic hypertension. JAMA 1999; 282:539-546.

- Verdecchia P. Prognostic value of ambulatory blood pressure: current evidence and clinical implications. Hypertension 2000; 35:844-881.

- Kario K, Pickering TG, Matsuo T, Hoshide S, Schwartz JE, Shimada K. Stroke prognosis and abnormal nocturnal blood pressure falls in older hypertensives. Hypertension 2001; 38:852-857.

- Mancia G, Sega R, Bravi C, De Vito G, Valagussa F, Cesana G, et al. Ambulatory blood pressure normality: results from the PAMELA study. J Hypertens 1995; 13:1377-1390.

- Ohkubo T, Imai Y, Tsuji I, Nagai K, Ito S, Satoh H, Hisamichi S. Reference values for 24-h ambulatory blood pressure monitoring based on a prognostic criterion: the Ohasama Study. Hypertension 1998; 32:255- 259.

- O'Brien E, Asmar R, Beilin L, Imai Y, Mallion JM, Mancia G, et al. European Society of Hypertension recommendations for conventional, ambulatory and home blood pressure measurement. J Hypertens 2003; 21:821-848.

- Zachariah PK, Sheps SG, Ilstrup DM. Blood pressure load: a better determinant of hypertension. Mayo Clin Proc 1988; 63:1085-1091.

- Hermida RC, Ferna ´ndez JR, Mojo ´n A, Ayala DE. Reproducibility of the hyperbaric index as a measure of blood pressure excess. Hypertension 2000; 35:118-125.

- Mancia G, Ferrari A, Gregorini L, Parati G, Pomidossi G, Bertinieri G, et al. Blood pressure and heart rate variabilities in normotensive and hypertensive human beings. Circ Res 1983; 53:96-104.

- Schillaci G, Pasqualini L, Verdecchia P, Vaudo G. Prognostic significance of left ventricular diastolic dysfunction in essential hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002; 39:2005-2011.

- Sega R, Cesana G, Bombelli M, Grassi G, Stella M, Zanchetti A, Mancia G. Seasonal variations in home and ambulatory blood pressure in the PAMELA population. J Hypertens 1998; 16:1585-1592.

- Mancia G, Zanchetti A, Agabiti Rosei EG, De Cesaris R, Fogari R, Pessina A, et al. Ambulatory blood pressure is superior to clinic blood pressure in predicting treatment-induced regression of left ventricular hypertrophy. Circulation 1997; 95:1464-1470.

- Rodrı ´guez-Roa E, Octavio JA, Mayorca E, Castro P, Miranda R, Valecillos E, Gonza ´lez M. Blood pressure response in 24 h in patients with high blood pressure treated with two nifedipine formulations once a day. J Hum Hypertens 2002; 16 (Suppl 1):S151-S155.

- Schettini C, Bianchi M, Nieto F, Sandoya E, Senra H. Ambulatory blood pressure normality and comparison with other measurements. Hypertension 1999; 34 (Pt 2):818-825.

- Kario K, Schwartz J, Pickering T. Ambulatory physical activity as a determinant of diurnal blood pressure variation. Hypertension 1999; 34:685-691.

- Omboni S, Parati G, Palatini P, Vanasia A, Muiesan ML, Cuspidi C, et al. Reproducibility and clinical value of nocturnal hypotension: prospective evidence from the SAMPLE study. J Hypertens 1998; 16:733-738.

- Hansen TW, Jeppesen J, Rasmussen S, Ibsen H, Torp-Pedersen C. Ambulatory blood pressure and mortality: a population-based study. Hypertension 2005; 45:499-504.

- Stanton A, Cox J, Atkins N, O'Malley K, O'Brien E. Cumulative sums in quantifying circadian blood pressure patterns. Hypertension 1992; 19:93-101.