K'awiil Chan K'inich, Lord of K'an Hix: Royal titles and Symbols of Rulership at Cahal Pech, Belize (original) (raw)

K’awiil Chan K’inich, Lord of K’an Hix: Royal titles and Symbols of Rulership at Cahal Pech, Belize.

Jaime J. Awe and Marc Zender

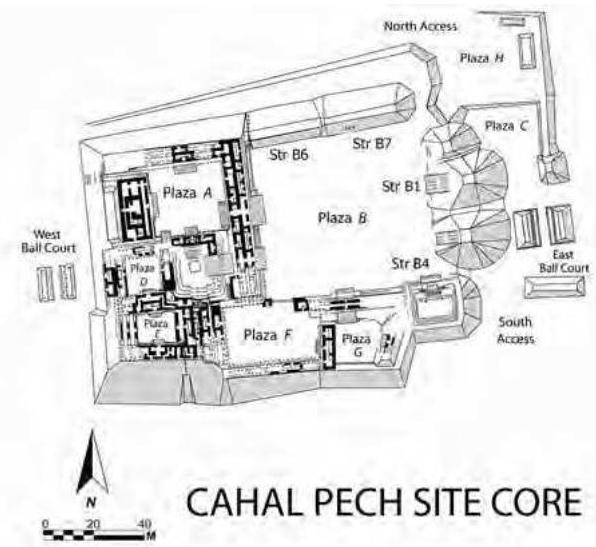

Recent Archaeological investigations in the site core at Cahal Pech, Belize (Fig. 1) uncovered a series of tombs and crypts in Structure B1, the central pyramid of the site’s eastern triadic assemblage (sometimes referred to as E-Group). Two of the tombs, Burials B1-2 and B1-7, contained rich assemblages of cultural remains that clearly serve to identify the graves as those of members of the ruling lineage of this Belize Valley center (Awe 2013). Among the most significant discoveries in the tombs were three bone rings, a bone pin, and fragments of turtle shell that were decorated with low-relief inscriptions. The inscriptions, along with the rich contents of the tomb, provide compelling evidence that Classic period Belize Valley elite employed symbols of rulership that are more typically associated with elite rulers of tier one polities (such as Tikal, Calakmul and Caracol) in the Maya lowlands (see Martin and Grube 2008:17-21). We provide here a brief description of the contexts in which the artifacts mentioned above were discovered, and we present our preliminary interpretation of the inscriptions on the rings, pin, and turtle shell.

Contexts of Burial B1-2 and B1-7

As indicated above, Burials B1-2 and B1-7 were discovered within Str. B1 (Fig. 2), the central pyramid of the site’s “EGroup” or eastern triadic assemblage (see J. Awe, J. Hoggarth, and J. Aimers, in press).

Burial B1-2

Burial B1-2 was initially excavated by Peter Schmidt in 1969. Although Schmidt never published a report of his investigations, archived copies of his notes at the Belize Institute of Archaeology indicate that the burial was placed in a large

tomb located approximately 1.5 meters below the summit of Str. B1. The tomb contained the remains of a single adult individual. Schmidt’s notes, and his illustration of the burial, indicate that the individual was lying in an extended position with head to the south, an orientation typical of Belize Valley burials (see Awe 2013).

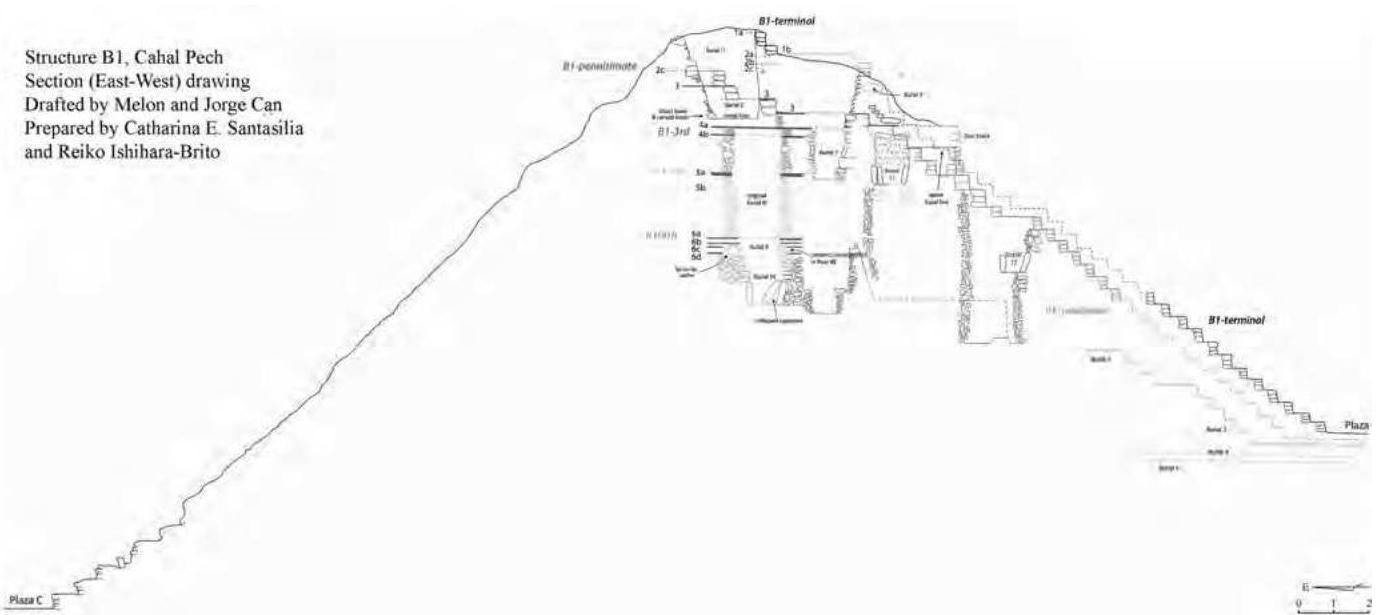

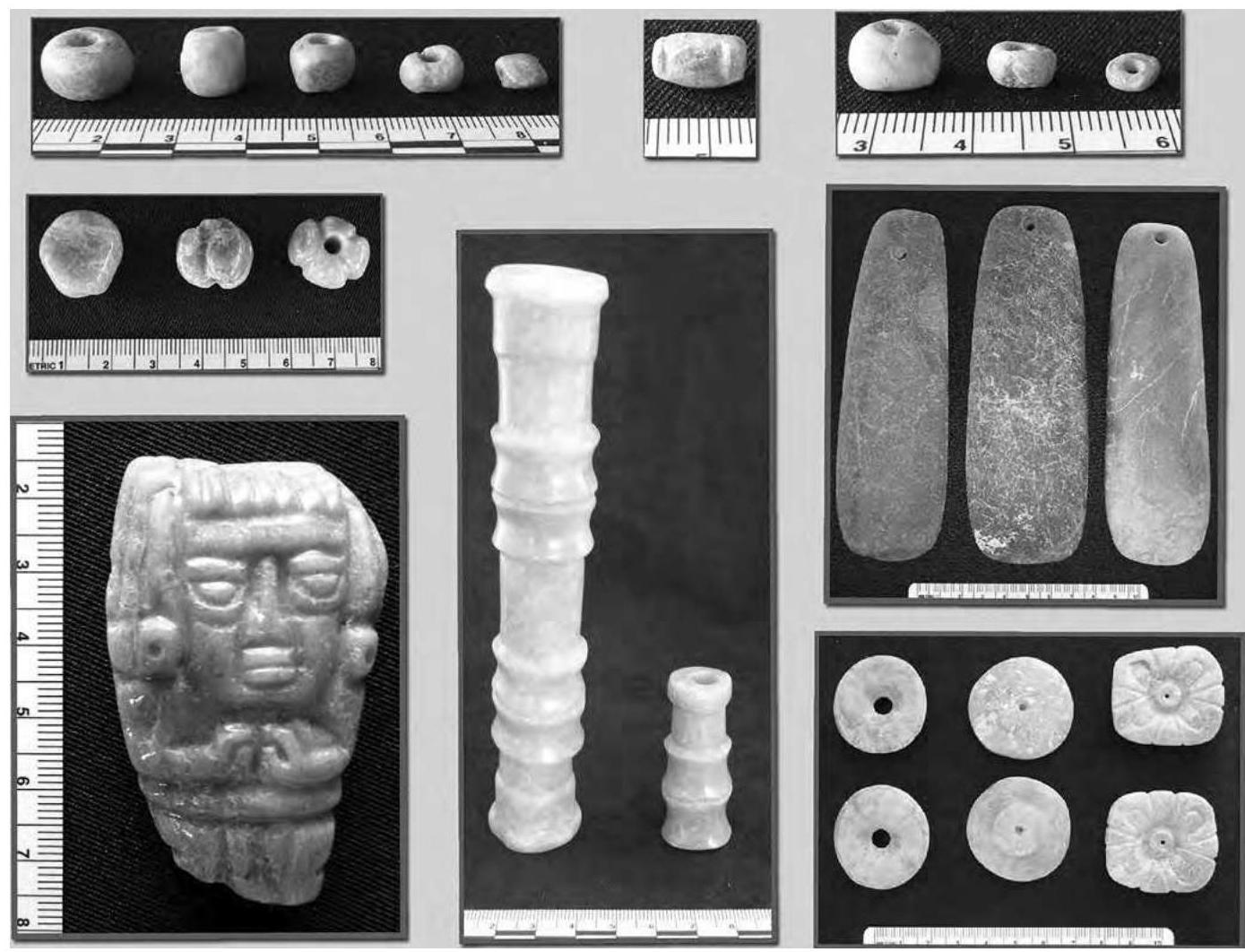

Burial B1-2 contained a large and diverse assemblage of grave goods (Figs. 3-4). Above the pelvis of the individual was a beautiful anthropomorphic mask made from several pieces of jadeite and marine shell. Other polished stone objects included six jade beads, six jade ear flares, a perforated jade tube, and three jade celts. A similar set of jade tubes

Fig. 1. Map of Cahal Pech site core (map by BVAR Project, prepared by Mark Campbell, Christophe Helmke, Rafael Guerra).

Fig. 2. Section plan of Str. B1, Cahal Pech (plan and illustration prepared by Merle Alfaro (Melon), Jorge Can, Catharina Santasilia, and Reiko Ishihara)

and celts were found in Burial B1-7. Two additional mosaic masks, made predominantly from shell with a couple pieces of jade, were located just below the skull, and several obsidian blades were placed near the feet of the individual.

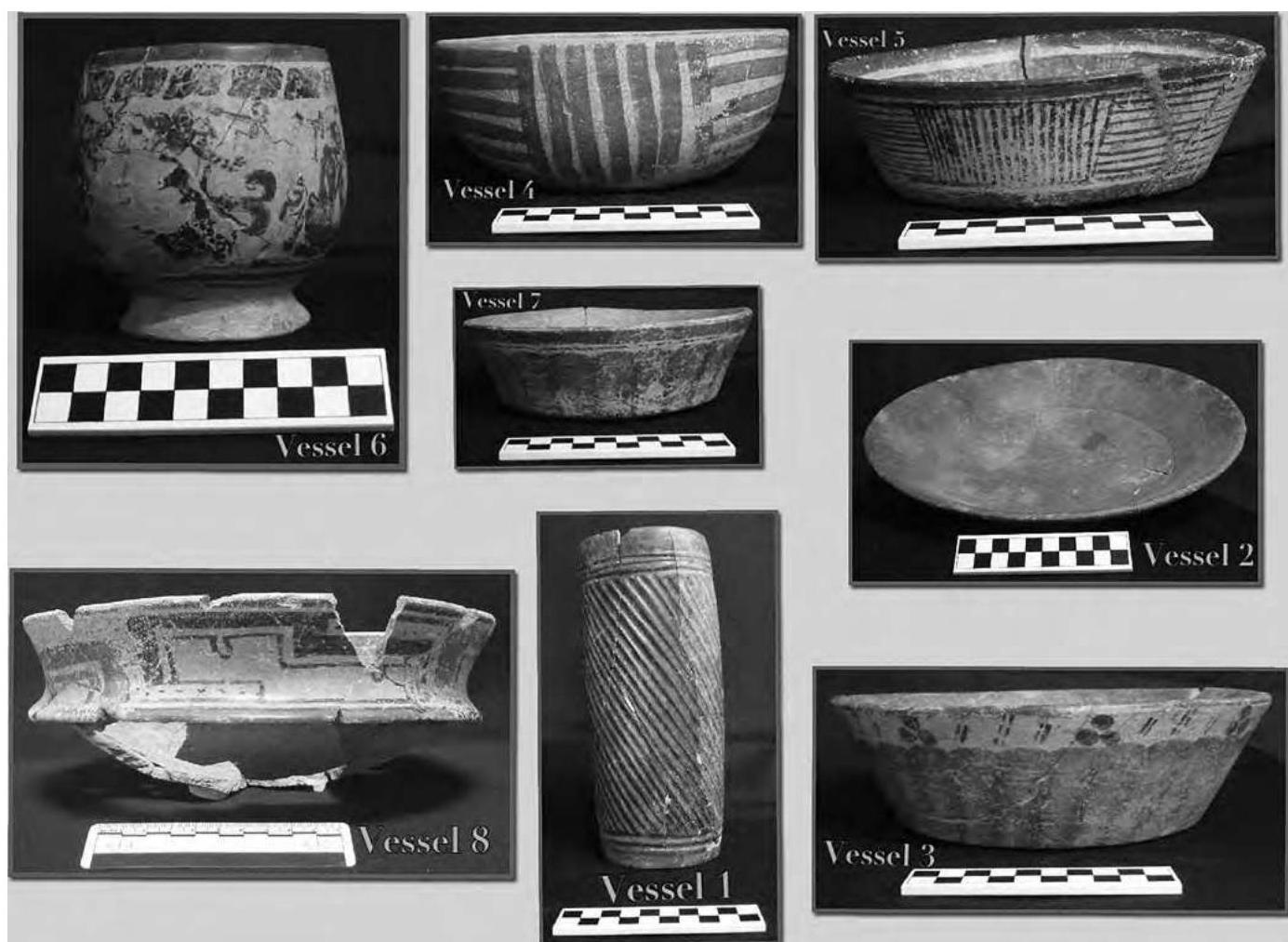

Ceramic artifacts included eight pottery vessels (Fig. 4). Six of the vessels were polychrome and two were monochrome. One of the vessels, a Saxche Cream polychrome (Fig. 4, Vessel 6), is chaliced-shaped and depicts an individual in the act of autosacrificial blood-letting (see Stone 1987:37, 1995). Another vessel (Fig. 4, Vessel 6), a basal flanged bowl, is typical of Early Classic Dos Arroyos Orange polychromes. There is also a brown fluted vase (Fig. 4, Vessel 1) that is similar in form and stylistic treatment to an early Late Classic fluted vase from Burial B1-7. These and other similarities between Burials B1-2 and B1-7 suggest an almost coeval date for the two burials with, B1-7 predating B1-2 by a few years at most.

In an effort to accurately record the stratigraphy of Str. B1, and to explore for other possible burials below the location of Burial B1-2, we reopened, in 2012, the area where Schmidt had excavated in 1969. This operation not only identified the original location of Burial B1-2, but also located several fragments of turtle shell in the unexcavated northeastern corner of the grave. Although the shell fragments were poorly preserved, a few glyphs, carved in low relief, were still discernible on the surfaces of the plastron fragments (see Figs. 8-10). The significance of these glyphs, and other

inscriptions carved on grave goods found in Burial B1-7, are described further below.

Burial B1-7

Burial B1-7 was also discovered in a large tomb about 3 m below the summit platform of Str. B1, and just west of where Burial B1-2 was located (Santasilia 2012, 2013). Although the human remains in the grave were in a very poor state of preservation, we were able to determine that the burial contained the skeletal remains of at least three adult individuals (Novotny et al. 2015). The earliest individual (Individual 3) interred in the tomb was represented by the articulated bones of the feet, and fragments of lower limb bones such as the fibula. These remains were discovered at the north end of the chamber, indicating an orientation with the head to the south. The rest of the skeleton was not found in situ but the discovery of skeletal fragments inside some of the pottery vessels, and throughout the fill in the tomb, suggests that the remains of this individual (Individual 3) was likely disturbed during the subsequent interment of Individual 2 and then redeposited throughout the tomb. Although multiple burials are conspicuously rare in the upper Belize River Valley, this tradition is typical at sites in the Chiquibul sub-region of western Belize, notably at Caracol (Chase and Chase 1996), Caledonia (Healy et al. 1998) and the upper Macal River drainage (Awe et al. 2005).

Fig. 3. Jade and shell artifacts from Burial B1-2 (photographs by Catharina Santasilia and Jaime Awe).

The remains of the second individual (Individual 2), an adult male, “was interred slightly above and to the east of the deposit of foot bones” (Novotny 2012). Individual 2 was “laid in an extended, supine position with head oriented to the north”. Like Individual 3, some of the remains of Individual 2 were not in anatomical position. This suggests that the tomb was reopened yet again for the interment of Individual 1. According to Novotny (2012:10), this likely occurred when the body of Individual 2 “was mostly, but not completely, decomposed.” Individual 1, an adult female, was interred directly above Individual 2 in a supine and extended position with head to the north.

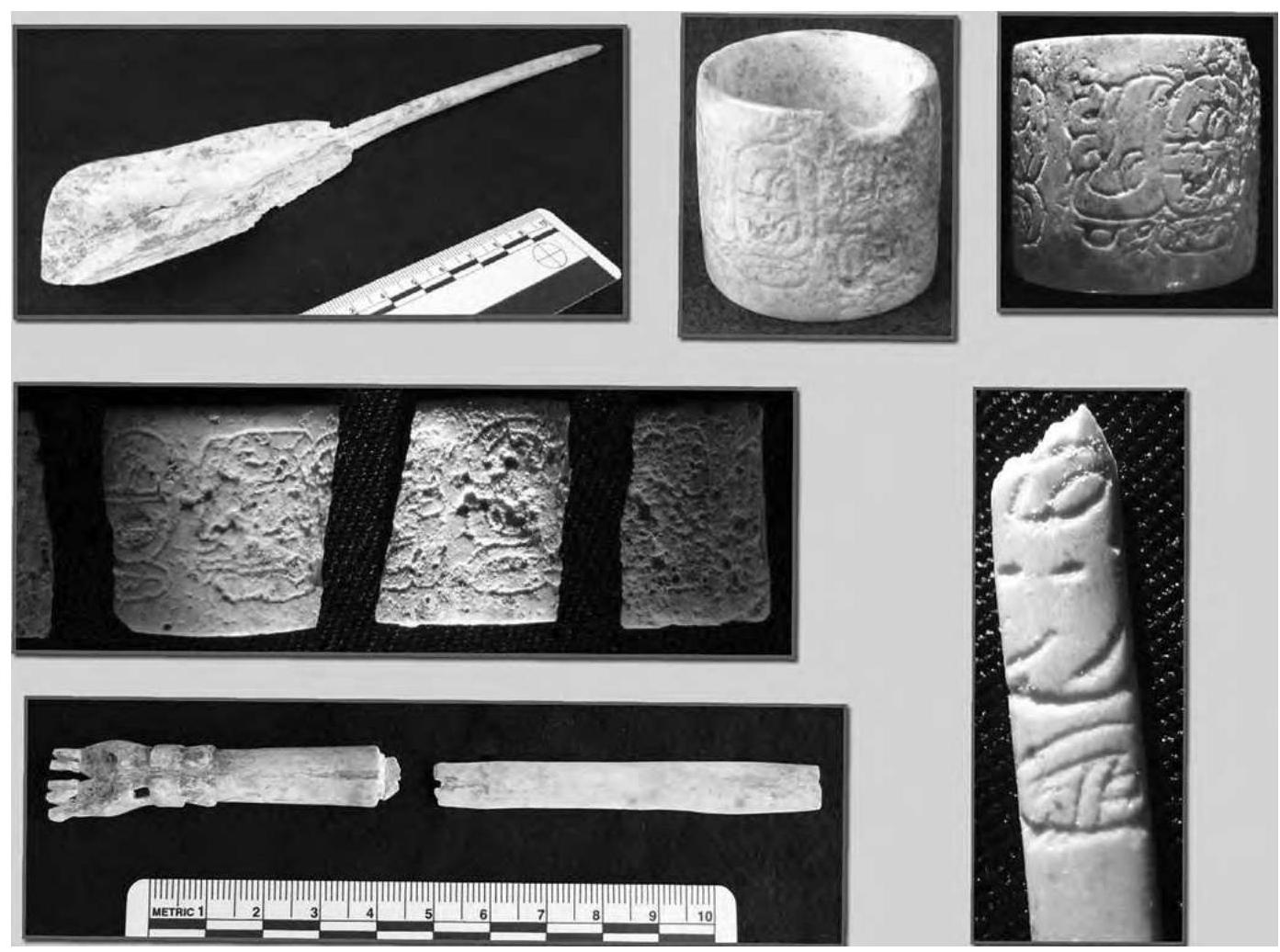

Burial B1-7 contained the largest number of grave goods of any burial yet discovered at Cahal Pech. The eight ceramic vessels (Fig. 5) in the tomb included two Early Classic, basalflanged, Dos Arroyos Orange polychrome bowls, a stuccoed vase, a bichrome bowl, a Late Classic Silkgrass fluted vase, and three monochrome red dishes. Polished stone objects (Fig. 6) included 12 jade beads, three jade celts or belt plaques, two jade bar pendants, a jade effigy pendant depicting the maize god, and three pairs of jade ear flares. Shell and bone objects (Fig. 7) were represented by three deer antler rings, eight bone scribal styli, three bone pins, four shell *adornos* with obsidian and *Spondylus* shell inlays, a shell inkpot with the remains of red, black, yellow and blue pigments, a bone spatula carved with a hand design, a necklace made from dog teeth, seven spindle whorls, and numerous other small objects. One of the bone pins and two of the deer antler rings were carved and inscribed. Stylistic analysis of the ceramic vessels from the tomb, glyphic paleography, and radiometric dating of the human remains, all suggest that the burials date sometime between the end of the Early Classic period, and the start of the Late Classic (AD 550 – 650) (Awe 2013; Novotny et al. 2015; Zender 2014).

Analysis of the Inscriptions on the Turtle Shell Fragments and Rings

Since there is no particular ordering principle at work in the inscriptions on the turtle shell, bone rings, and bone needles – that is, they are not part of a larger epigraphic program, none of them contain hieroglyphic dates, and there is no indication of topical overlap – we will present them, purely for convenience, in the numerical order of the burials from which they stem.

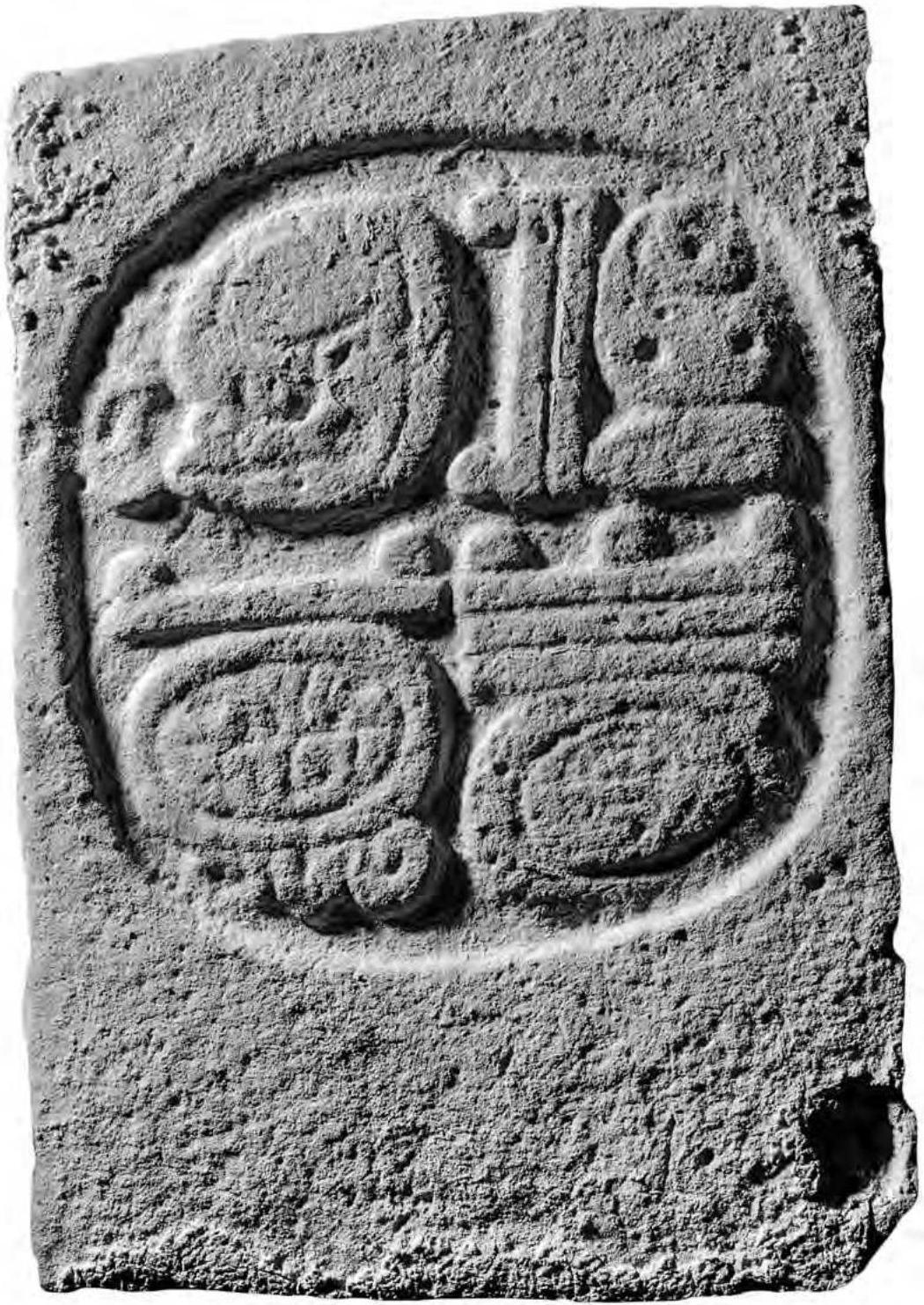

Incised Turtle Shell Fragments from Burial B1-2

As we noted above, the incised turtle shell fragments were recovered during our 2012 excavations of the area where Peter Schmidt had located Burial B1-2 in 1969. Although still unpublished, many of the materials recovered from this burial are curated in the Institute of Archaeology, as are some of Schmidt’s notes and a plan of the burial. These, coupled with the compact nature of the incised turtle shell fragments discovered in 2012 (see Fig. 8 below), make it likely, but not certain, that no earlier fragments had come to light in 1969 (if they did, then apparently they no longer survive).

Fig. 4. Ceramic vessels from Burial B1-2 (photographs by Catharina Santasilia and Jaime Awe).

Fig. 5. Ceramic vessels and shell objects from Burial B1-7 (photographs by Jaime Awe and Catharina Santasilia)

According to Norbert Stanchly (pers. comm. 2012), the fragments are part of the upper (dorsal) carapace of an American Freshwater Turtle (or Slider). Stanchly’s ongoing investigation of the animal remains from the burial should provide an independent check on whether the entirety of the shell is present, and whether or not we should consider that some earlier fragments may have been excavated by Schmidt. On present evidence, it seems that the entirety of the dorsal carapace was once carved/incised with a linear design, some of which was apparently in-filled with hematite (iron oxide).

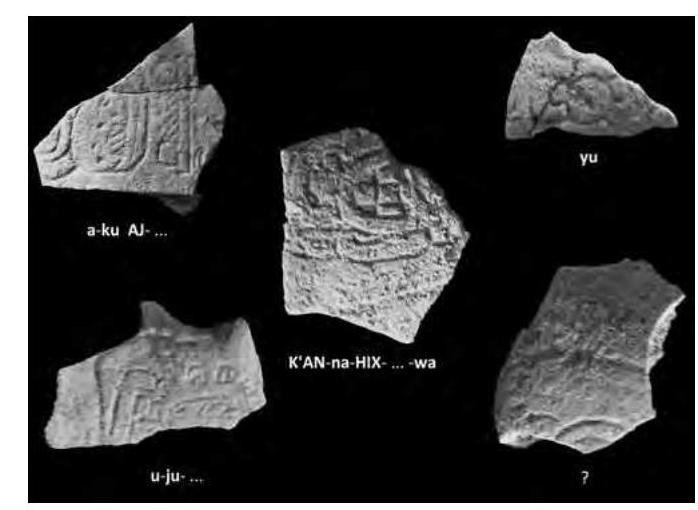

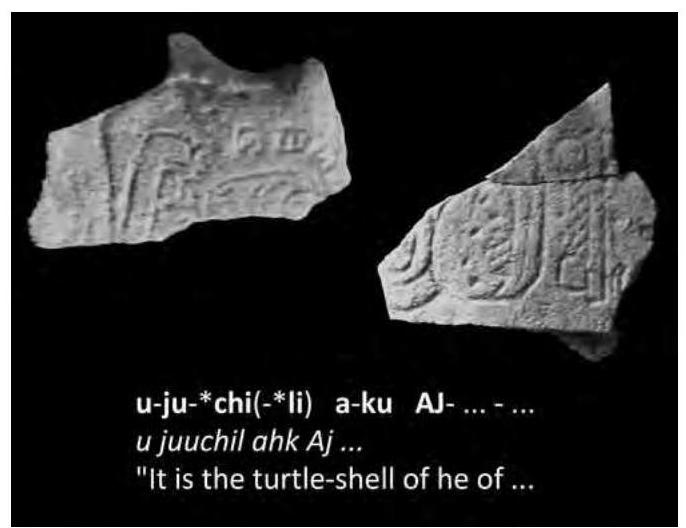

The remains are now too fragmentary to be certain as to what the design represented. Additionally, six fragments contain traces of a hieroglyphic inscription, which once ran bilaterally across the ventral carapace. These do not form a complete text, suggesting that a significant amount of the original object is missing.

The first large fragment (Fig. 8, upper left) reveals the badly eroded verb pa-ta-la-ja, patlaj ‘it was fashioned.’ This may have been the initial glyph of the inscription, but it is impossible to discount the possibility of other introductory material, such as calendrical information or adverbs, given comparable inscriptions on other portable objects.

The five remaining fragments with hieroglyphic inscriptions can be seen in Figure 9, each of which bears partial remains of one to two glyph blocks. Their order is for the most part uncertain (though see below), but the individual hieroglyphs can be read as follows:

- aku AJ…, Ahk Aj…, ‘turtle, he of …’

- uju…, uju…, ‘his/her/its ju…’

- K’AN-na-*HIX-…-wa, K’an Hix …w, ‘Yellow/Tawny Jaguar …’

- yu-…, yu…, ‘his/her/its …’

- ?

The spelling aku for ahk ‘turtle’ is very common in Mayan hieroglyphic inscriptions, frequently appearing in the names of both humans and gods. Coupled with the fragmentary nature of the inscription (much of the text is certainly missing) this explains why we did not initially connect the spelling to the object this text was incised on: namely, a turtle shell. But given the fragmentary uju… spelling, which could conceivably have once recorded ujuchi(li), ujuuch(il) ‘his/her/its shell’, a common collocation on other carved shells, we speculate that these two fragments once provided the sequence ujuchi(li) aku AJ… for ujuuch(il) ahk aj-…, or ‘It is the turtle-shell of aj- …’ (see Fig. 10). The aj- prefix frequently marks an agentive, appearing in titles of occupation (e.g., ajtz’ihb ‘scribe’) or origin (e.g., ajchikunahb ‘he of Calakmul’), so it is possible that the damaged signs which follow once provided this information for the owner of the shell.

Even more intriguing is the third turtle shell fragment, which records a nominal (perhaps titular) element also known from the two incised bone rings (to be discussed below), and which can be transcribed as K’ANnaHIX…wa. We will discuss this element in more detail below, but for now it will suffice to note that this is a strong candidate for a traditional title for Cahal Pech nobility.

To summarize the foregoing, this object appears to have been an incised turtle carapace. What its function was can only be guessed at; perhaps a drum like the musical instruments occasionally depicted in Maya art? Whether it was interred whole or already in fragments remains unknown and will have to await Norbert Stanchly’s analysis to determine how much of the carapace is missing. Like many portable objects, however, it apparently included a brief dedicatory text describing its fashioning, a brief description, and the name (and possibly title) of its owner, only part of which survives.

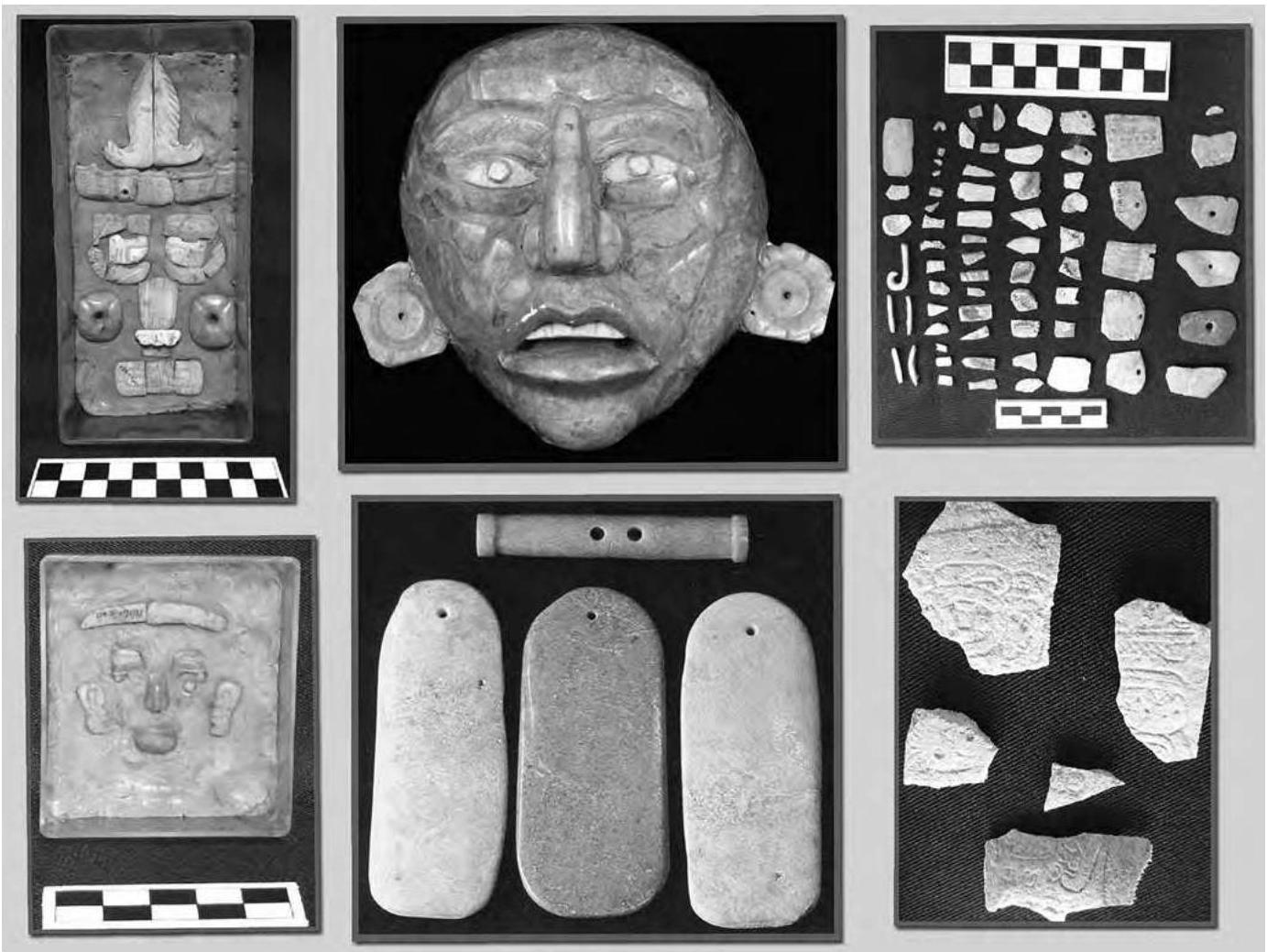

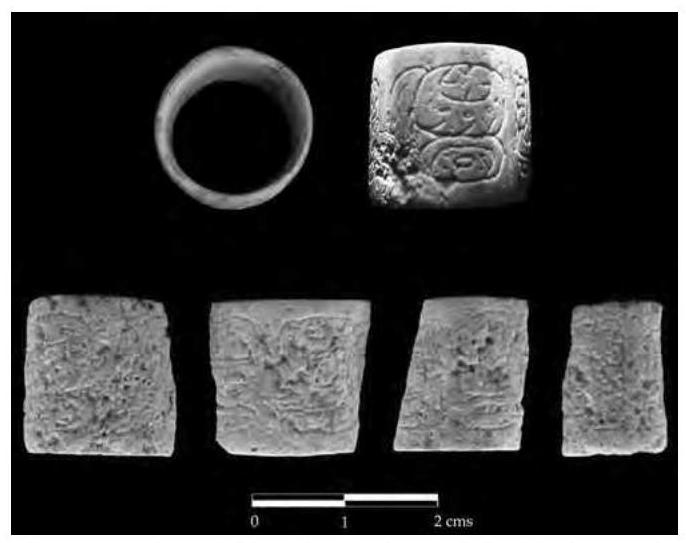

Incised Bone Rings from Burial B1-7

Among the rich offerings of jade, shell and bone discovered in Burial B1-7 at Cahal Pech, the two small incised bone rings are perhaps the most unique and distinctive (Fig. 11). Both suffered substantial erosion (mostly scratches and surface pitting) following their deposition in the tomb, though the first ring remains intact and is substantially better preserved, whereas the second was discovered in four roughly equal-sized fragments, and its inscription has suffered greatly as a result.

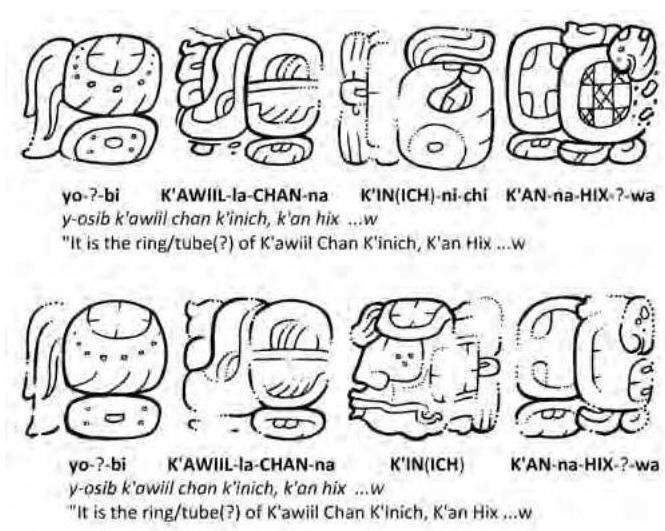

The rings are very small (less than two centimeters in diameter), very thin (2-3 mm thick, on average), and very finely incised, with glyph blocks about 1.5 cm square. Each ring bore four glyph blocks, and close analysis of the inscription reveals that the texts were perfectly parallel, the only textual variation coming from a well-attested glyphic substitution in the third block of the K’IN(ICH) logogram (on the more poorly-pre-

Fig. 6. Polished stone artifacts from Burial B1-7 (photographs by Jaime Awe and Catharina Santasilia).

served ring) for the logo-phonetic spelling K′IN(ICH)\mathbf{K}^{\prime} \mathbf{I N}(\mathbf{I C H}) nichi (on the better-preserved ring). Otherwise, and despite the erosion, the two texts are completely identical.

Both inscriptions were initially illustrated in our field laboratory. These were subsequently traced over circumferential photographs, and the drawings were later carefully checked against the original objects (Fig. 12).

Since practically all inscriptions on portable objects begin with a possessed “name tag” - such as ‘his cup’, ‘his bone’, etc. - it was obvious that these two inscriptions had to begin with the yo?-bi collocation, as indicated in the drawings. Ever since David Stuart’s (1987) publication detailing the decipherment of the syllable yo, it has been clear that this sign serves to record the third person possessive prefix yy on nouns beginning with the vowel oo, and there is no other potential possessive marker in either of these texts. Similarly, the syllable bi has been well-known since the 1950s, and has more recently been recognized as frequently providing the instrumental suffix ibi b (or −Vb-\mathrm{V} b ) on nouns derived from verbs (Houston et al. 2001).

The only mysterious element in this ‘name tag’ was the middle sign, often nicknamed ’ kk ‘in-imix’, because it resembles the ‘sun’ sign (K’IN) infixed into T501 Imix. However, the behavior of this sign in other contexts makes it clear that it represents a single CV syllable, not a compound. The sign is relatively rare, however, and has only been documented in the following different contexts:

(AJ-/a)#- … -ni (a common, but poorly understood title)

ya- … -ni (a possessed form of the title on K5070)

ju- … (Cancuen Panel 1, and Naj Tunich drawing 88)

AJ- … -su (Panel fragment, Denver Museum of Science and Nature)

… -sa (El Peru stelae [2 examples])

yo-…-bi (Cahal Pech [2 examples])

The contexts are not numerous, and they are not such that a strong phonetic value can yet be proposed that makes sense of all of them. Nonetheless, the new Cahal Pech context is sufficiently probative that it can be used to propose a tentative phonetic reading of so, which will require testing as new contexts emerge. The rationale for this reading stems from the following forms in relevant Mayan languages:

| Ch’ol | otz-an | ‘insert something’ (Aulie and |

|---|---|---|

| Aulie 1998:90) | ||

| <∗<* och-es-an | ||

| Chontal | os-en | ‘insert, place inside’ (Keller and |

| Luciano 1997:178) | ||

| <∗<* och-es-en | ||

| Ch’orti’ | os-e | ‘put inside, fit a thing in or on’ |

| (Hull 2005:91) | ||

| <∗<* och-es-e |

Fig. 7. Bone and shell artifacts from Burial B1-7 (photographs by Catharina Santasilia and Jaime Awe).

That is, Ch’olan languages have an intransitive verb root *och* ‘to enter’ that can be derived as a causative verb *oches* ‘to insert (i.e., make something enter/go in)’. Over time, the vowel of the *es* causativizer is syncopated and lost, probably due to the addition of still further suffixes and resultant stress shift, and this results in *-chs-*, which is an impermissible (and unpronounceable) consonant cluster. The modern languages handle this impermissible cluster in two different ways, either deleting the *ch* (Chontal and Ch’orti’), or transforming *chs*

Fig. 8. Photo of the incised turtle shell fragments as found *in situ* (photograph by Marc Zender).

to *tz* (Ch’ol). Note, too, that Charles Wisdom (1950:551) indicated Ch’orti’ *ose* as the verb of choice with reference to placing a ring on one’s finger in one of the entries in his dictionary: “*ose uor uk’ab makuiir e xoibir* (fit one’s finger into a ring)”. The language of Classic Mayan inscriptions is generally recognized to be closer to Eastern Ch’olan, of which Ch’orti’ is the sole surviving member. For this reason, we might expect an Eastern Ch’olan word for ‘ring’ to have been something like *osib*, from **ochesib* ‘thing for inserting (a finger into); a ring’, with the aforementioned syncopation

Fig. 9. Five turtle shell fragments with inscriptions from Burial B1-2 (photographs and analysis by Marc Zender).

Fig. 10. Suggested ordering of two turtle shell fragments (photographs and analysis by Marc Zender).

Fig. 11. Bone rings with inscriptions from Cahal Pech (photographs by Marc Zender).

and consonant shift. In its possessed form, in Mayan glyphs, a word for “ring” would therefore have been written as either **yosobi** or **yosibi**. Given that the ‘k’in-imix’ syllable never substitutes for the two known **si** signs, **so** presently emerges as the best candidate (see also Zender 2014), though we caution that more contexts are needed before this sign can be confidently regarded as deciphered.

Thankfully, the two glyph blocks following the possessed noun are much more transparent, and they provide the personal name K’awiil Chan K’inich. The name is a compound deity name common in Mayan inscriptions, meaning something like ‘the Sun God (K’inich) is like Lightning (K’awiil) in the Sky (Chan)’. And the name is already attested as that of a mid-8th century king of Dos Pilas, Guatemala (see Martin and Grube 2008:60-63), though here it must be that of a namesake. Whether it represents the name of one of the tomb’s occupants or of the original owner or commissioner of the ring (if an heirloom) cannot yet be ascertained.

The final glyph block on the rings also includes an undeciphered sign: **K’AN-na-HIX-** … **-wa**. The elements K’an Hix are clear enough, and probably mean ‘Yellow (or Tawny) Jaguar’. In an earlier study (Zender 2014), the junior author tentatively identified the jaguar-elements of these signs as

Fig. 12. Inscriptions on the two bone rings from Cahal Pech (drawings and analysis by Marc Zender).

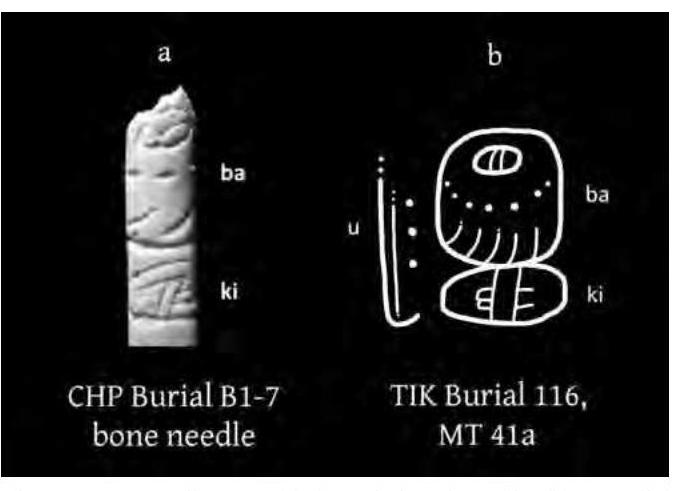

Fig. 13. Bone needle texts: (a) the Cahal Pech needle; (b) a parallel text from Tikal (photograph by Catharina Santasilia, drawing by Anne Seuffert).

**BAHLAM** rather than **HIX** (both of which basically mean ‘jaguar’), but the recent discovery of an incised jade plaque at Nim li Punit containing the same collocation clarifies that the sign in question is indeed **HIX** (Christian Prager, pers. comm. 2015). A remaining uncertainty is the sign T594a/b, which resembles a checkerboard and remains undeciphered. Despite being a well-known element in the hieroglyphic name of the Palenque patron god GIII (Prager 2015), there simply are not enough clues at present to propose a reading for this evident logogram. All that is clear at present is that the **wa** syllable which follows the sign three times at Cahal Pech, in several contexts at Palenque, Naj Tunich Cave (see Stone 1995:203, fig. 8-29b) and in the new Nim li Punit inscription, is an optional phonetic complement, suggesting that the T594 “checkerboard” sign registers a word ending in the sound *w*. That is, it is most likely a logogram for a word of the shape CV*w* or CVCV*w*.

That said, the appearance of the **K’AN-na-HIX-** … **-wa** collocation at the close of a nominal string on the rings (and on the incised turtle shell), suggests that it may have served as a title, perhaps a traditional title of nobility from Cahal Pech. Recently, as Christian Prager (pers. comm. 2015) informs us, another example of this title has been discovered on an

incised jade plaque at Nim li Punit, which might suggest that its bearer (a royal woman) hails from Cahal Pech. Further speculation will have to await additional contexts, but it is worth noting that, of four presently-known examples of this title, fully three of them appear at Cahal Pech.

Incised Bone Needle Fragment from Burial B1-7

Centrally located in Burial B1-7, but not recovered until screening and post-excavation cleaning of the finds, was a small fragment of an incised bone needle (Fig. 13a).

The fragmentary inscription is hardly dramatic, but enough survives to read it as baki, baak, ‘bone’. Like most portable objects with inscriptions, there was probably a possessive marker u preceding this short text, thereby rendering ubaki, ubaak, ‘his/her bone’. Several parallel inscriptions are known, most famously at Tikal (see Fig. 13b), as first identified by David Stuart (1984; see also Houston and Stuart 2001). As with the parallel texts, the possessed noun would have been followed by the name of the needle’s owner. Unfortunately, we did not recover any other fragments of the needle, thus this information has been lost to us.

Concluding Remarks

Considering the dearth of inscribed architectural and monumental texts at Cahal Pech, the discovery of four (admittedly brief) texts in three years of excavations of burials within Structure B1 is highly significant. It suggests that, like their elite counterparts at sites in the central lowlands, the Classic period elite rulers of Cahal Pech also manipulated inscrip-tion-bearing objects as a reflection of their royal status. Like Baking Pot and Altun Ha further down river, the material remains in the royal tombs at Cahal Pech further serve as tangible manifestations of the status, wealth, and power of this Belize River Valley center. It is quite likely that the affluence of these medium-size centers was a result of their ability to successfully exploit their advantageous location on an important central lowland Maya trading route. Hopefully, future research at Cahal Pech and other Belize Valley sites will yield additional historical information that will allow us to better understand the Classic period political landscape of this important Maya sub-region.

Acknowledgments

Investigations of the eastern triadic assemblage (or E-Group) at Cahal Pech were made possible by the generous support of the Tilden Family Foundation, and with the kind permission of the Institute of Archaeology, National Institute of Culture and History, Belize. Excavations of the triadic group at Cahal Pech were conducted by Catharina Santasilia, Doug Tilden, Jorge Can, Merle (Melon) Alfaro, Jim Puc Sr., Jim Puc Jr., Eduardo Cunil, Antonio Itza, Ashley McKeown, Anna Novotny, Rosie Bongiovanni, Kirsten Green and Caitlin Stewart. We thank these colleagues for their insights, hard work, and many contributions to the success of our research at Cahal Pech. Considerable gratitude is extended to Julie Hoggarth, Rafael Guerra, Claire Ebert, Mat Saunders, Jim and Christy Pritchard, and all the staff, students and workers of the 20112014 Belize Valley Archaeological Reconnaissance Project for their professional assistance and support. We also want to thank Christophe Helmke for his insightful comments and review of the paper.

Abstract: Hieroglyphic inscriptions provide one of the most important sources of information on Classic period Maya rulers, and on the sociopolitical relations between lowland Maya polities. The discovery of new inscribed monuments and artifacts, particularly in Maya sub-regions where inscriptions are rare, can therefore provide critical new information on the political significance of these sites. In this paper, we describe the recent discovery at Cahal Pech of three bone rings, a bone pin, and fragments of turtle shell that were decorated with low-relief inscriptions. The hieroglyphic texts from Cahal Pech, along with the rich contents of the tomb where the artifacts were discovered, provide compelling evidence that Classic period Belize Valley elite employed symbols of rulership akin to those used by the powerful rulers of larger centers in the Maya lowlands.

Resumen: Inscripciones jeroglíficas proveen una de las fuentes de información más importantes sobre los gobernantes mayas del periodo Clásico y sobre las relaciones socio-políticas entre las entidades políticas de las tierras bajas mayas. El descubrimiento de nuevos monumentos y artefactos inscritos, particularmente en las sub-regiones Mayas donde las inscripciones son raras, pueden por lo tanto proveer nueva información crítica sobre el significado político de estos sitios. En este artículo, describimos el reciente descubrimiento en Cahal Pech de tres anillos de hueso, un alfiler de hueso y fragmentos de caparazón de tortuga, los cuales estuvieron decorados con inscripciones de bajo relieve. Los textos jeroglíficos de Cahal Pech, junto con los ricos contenidos de la tumba en la cual los objetos fueron descubiertos, proveen evidencia convincente de que la élite del Valle de Belize del periodo Clásico empleó símbolos de soberanía semejantes a aquéllos usados por los poderosos gobernantes de los grandes centros de las tierras bajas Mayas.

Zusammenfassung: Hieroglypheninschriften bilden eine der wichtigsten Quellen für Information über die Herrscher der Maya der Klassischen Zeit, sowie über die sozio-politischen Beziehungen zwischen den Staaten des Maya-Tieflands. Die Entdeckung von neuen beschrifteten Monumenten, insbesondere in Subregionen der Maya-Welt in denen Inschriften ansonsten selten sind, kann deshalb wichtige neue Information über die politische Bedeutung dieser Stätten liefern. In diesem Artikel beschreiben wir die erst kürzlich in Cahal Pech entdeckten drei Knochenringe, eine Knochenmadel und Fragmente von Schildkrötenpanzern, die mit Inschriften im Flachrelief beschriftet sind. Die Inschriften von Cahal Pech, zusammen mit dem reichen Inhalt des Grabes wo die Artefakte gefunden wurden liefern eindeutige Hinweise darauf, dass die Elite des Belize Valley in der Klassik die gleichen Symbole der Herrschaft verwendete wie mächtigere Herrscher aus den groBen Zentren des Maya-Tieflands.

References

Awe, Jaime J.

2013 Journey on the Cahal Pech Time Machine: An Archaeological Reconstruction of the Dynastic Sequence at a Belize Valley Polity. Research Reports in Belizean Archaelogy 10: 33-50.

Awe, Jaime J., Julie A. Hoggarth and James J. Aimers

in press Of Apples and Oranges: The Case of E-groups and Eastern Triadic Architectural Assemblages in the Belize River Valley. In Early Maya E-Groups, Solar Calendars, and the Role of Astronomy in the Rise of Lowland Maya Urbanism, edited by David A. Freidel, Arlen F. Chase, Anne Dowd, and A. Murdock. Gainesville: University Press of Florida.

Awe, Jaime J. Douglas M. Weinberg, Rafael Guerra, and Myka Schwanke

2005 Archaeological Mitigation in the Upper Macal River Valley: Final Report Of Investigations Conducted Between June - December 2003, January -March 2004, October-December 2004.

Aulie, H. Wilbur and Evelyn W. de Aulie

1998 Diccionario Ch’ol de Tumbalá, Chiapas, con variaciones dialectales de Tila y Sabanilla. Mexico: Summer Institute of Linguistics.

Chase, Diane Z., and Arlen E Chase

1996 Maya Multiplex: Individuals, Entries, and Tombs in Structure A34 of Caracol. Latin American Antiquity 7 (1): 61-79.

Healy, Paul F., Jaime J. Awe and Herman Helmuth

1998 Excavations at Caledonia (Cayo), Belize: An Ancient Maya Multiple Burial. Journal of Field Archaeology 25(3): 261-274.

Houston, Stephen D., John Robertson, and David Stuart

2001 Quality and Quantity in Glyphic Nouns and Adjectives. Research Reports on Ancient Maya Writing 47. Washington, D.C.: Center for Maya Research.

Houston, Stephen D. & David Stuart

2001 Peopling the Classic Maya Court. Royal Courts of the Ancient Maya, Vol. 1: Theory, Comparison, and Synthesis, edited by Takeshi Inomata & Stephen D. Houston, pp. 54-83. Westview Press, Boulder.

Hull, Kerry

2005 An Abbreviated Dictionary of Ch’orti’ Maya. www.famsi.org/reports/ 03031/03031 /

Keller, Kathryn C. and Plácido Luciano

1997 Diccionario Chontal de Tabasco. Mexico: Summer Institute of Linguistics.

Martin, Simon, and Nikolai Grube

2008 Chronicle of the Maya Kings and Queens. Second edition. London: Thames and Hudson.

Novotny, Anna

2012 Osteological Analysis of Burials B1-1, B1-2, and B1-3 from Tomb 1, Structure B1, Cahal Pech. In The Belize Valley Archaeological Reconnaissance Project: A Report of the 2011 Field Season, edited by Julie A. Hoggarth, Rafael A. Guerra, and Jaime J. Awe, pp. 56-71. Belmopan: Institute of Archaeology, National Institute of Culture and History.

Novotny, Anna, Jaime J. Awe, Catharina Santasilia, and Kelley Knudson

2015 Bioarchaeological Analysis of an Ancient Maya Ancestral Context at Cahal Pech, San Ignacio, Belize. Paper presented at the 80th Annual Meeting of the Society for American Archaeology, April 15-19, San Francisco.

Prager, Christian

2015 Is T594 Logograph for BAL(AW) “cloth, cover, textile”? Manuscript in Possession of Author.

Santasilia, Catharina E.

2012 The Discovery of an Elite Maya Tomb: Excavations at the Summit of Structure B1 at Cahal Pech, Belize. In The Belize Valley Archaeological Reconnaissance Project: A Report of the 2011 Field Season, edited by Julie A. Hoggarth, Rafael A. Guerra, and Jaime J. Awe, pp. 35-55, Belmopan: Institute of Archaeology, National Institute of Culture and History.

2015 Investigations of a Late Classic Elite Burial at the Summit of Structure B1 at the site of Cahal Pech, Belize. Master’s Thesis. Copenhagen: Faculty of Humanities, University of Copenhagen.

Stone, Andrea

1987 Commentary. Mexicon 9(2): 37.

1995 Images from the Underworld: Naj Tunich and the Tradition of Maya Cave Painting. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Stuart, David

1984 Additional Examples of Hieroglyphic “Name-tagging” on Some Bone Artifacts from Tikal. Manuscript in possession of the authors.

1987 Ten Phonetic Syllables. Research Reports on Ancient Maya Writing 14. Washington, D.C.: Center for Maya Research.

Wisdom, Charles

1950 Materials on the Chorti Language. Microfilm Collection of Manuscripts on Middle American Cultural Anthropology, No. 28. Chicago: University of Chicago Library.

Zender, Marc

2014 Glyphic Inscriptions of the Structure B1 Burials at Cahal Pech, 20112012. In The Belize Valley Archaeological Reconnaissance Project: A Report of the 2013 Field Season, edited by Julie A. Hoggarth and Jaime J. Awe, pp. 52-60. Belmopan: Institute of Archaeology, National Institute of Culture and History.

Recent Publications

Books

mexicon is intent on providing the most up-to-date information on publications relating to Mesoamerica.

We are most grateful for any data you can provide us at bibliomex@mexicon.de

Coleman, Kevin

2016 A camera in the garden of Eden: the self-forging of a banana republic. Austin: University of Texas Press. 312 pp., ISBN 978−1477308554978-1477308554.

Cook, Suzanne

2016 The forest of the Lacandon Maya: an ethnobotanical guide. Springer, Boston, MA. 379 pp. Boston: Springer, 379 pp. 9781461491118.

Dowd, Anne S. and Susan Milbrath (eds.)

2015 Cosmology, calendars, and horizon-based astronomy in ancient Mesoamerica. Boulder: University Press of Colorado. 440 pp., 172 figs. ISBN 978-1607323785.

(Content: Susan Milbrath and Anne S. Dowd: An Interdisciplin-

ary Approach to Cosmology, Calendars, and Horizon-Based Astronomy, pp. 3-18; Ivan Šprajc: Pyramids Marking Time: Anthony F. Aveni’s: Contribution to the Study of Astronomical Alignments in Mesoamerican Architecture, pp. 19-36; Anne S. Dowd: Maya Architectural Hierophanies, pp. 37-76;Ronald K. Faulseit: Mountain of Sustenance: Site Organization at DainzúMacuilxóchitl and Mesoamerican Concepts of Space and Time, pp. 77-100; Clemency Coggins: The North Celestial Pole in Ancient Mesoamerica, pp. 101-138; Susan Milbrath: A Seasonal Calendar in the Codex Borgia, pp. 139-162; Gabrielle Vail: Iconography and Metaphorical Expressions Pertaining to Eclipses: A Perspective from Postclassic and Colonial Maya Manuscripts, pp. 163-196; John B. Carlson: The Maya Deluge Myth and Dresden Codex Page 74: Not the End but the Eternal Regeneration of the World, pp. 197-228; Flora Simmons

mexicon

Zeitschrift für Mesoamerikaforschung

Journal of Mesoamerican Studies - Revista sobre Estudios Mesoamericanos

Vol. XXXVIII

Dezember 2016

Nr. 6