The development of centralised societies in Greater Mesopotamia and the foundation of economic inequality (original) (raw)

The development of centralised societies in Greater Mesopotamia and the foundation of economic inequality

Marcella Frangipane

Zusammenfassung

Die Entwicklung zentralisierter Gesellschaften in Großmesopotamien und die Begründung wirtschaftlicher Ungleichheit

Nach einer kurzen Übersicht über die verschiedenen Formen und Stufen der sozialen Differenzierung, welche in einem allgemeinen Konzept von »Ungleichheit« enthalten sein können, soll die Art der »ungleichen sozialen Beziehungen« beschrieben werden. Dabei wird der Schwerpunkt auf die Wahrscheinlichkeit, dass aus gewissen sozialen Unterschieden echte sozioökonomische Missverhältnisse sowie bestimmte Formen permanenter politischer Macht entstehen, gelegt. Hierfür werden sowohl spezifische Arten von solchen Ungleichheiten zugrundeliegenden sozialen Bedingungen sowie verschiedene Umstände und Voraussetzungen für das Funktionieren von Subsistenzwirtschaftssystemen betrachtet.

In einem zweiten Schritt wird versucht, die Eigenschaften der frühesten ungleichen und hierarchisch gegliederten sozialen Beziehungen innerhalb der Gesellschaftssysteme im Nahen Osten zu untersuchen, indem deren wirtschaftliche und/oder politische Grundlagen, insbesondere im Hinblick auf Mesopotamien und dessen Umfeld im 4.Jt. v.Chr., herausgearbeitet werden. Diese Region liefert sehr interessante Beispiele für den Übergang von Gesellschaften mit einfachen Rangordnungen zu effektiv hierarchisch organisierten Systemen, die auf eine zunehmende Zentralisierung von primären Rohstoffen sowie von Arbeitskraft beruhen; auch bietet sie relevante Daten für eine Untersuchung der Dynamik des Wandels, die zur Entstehung von frühen staatähnlichen Gesellschaften führte.

Der Beitrag untersucht die historischen Wurzeln des Wandels, der im südlichen Mesopotamien stattfand, von gewissen Formen der hierarchischen Verwandtschaftsbeziehungen, die sich in der Obed-Zeit (5. Jt. v. Chr.) erkennen lassen, zur Entstehung von ungleichen wirtschaftlichen und politischen Netzwerken in den späten Phasen der Uruk-Zeit. Dieser Wandel führte zur Entstehung von streng zentralisierten Machtsystemen. Da Ungleichheit auf Unterordnung beruht, geht sie einher mit dem Aufkommen von »Macht" und dem ungleich verteilten Zugang zu Rohstoffen; ein Prozess der auch in anderen Regionen Nordmesopotamiens und Südostanatoliens stattfand, wie eine vergleichende Untersuchung zeigt.

Schließlich soll der Fall von Arslantepe in der oberen Euphratregion detailliert vorgestellt und der Übergang von Prestige-zu Machtsystemen, beziehungsweise vom Herstellen eines religiös-ideologischen Konsenses aufgrund öffentlicher Zeremonien zur Machtausübung in einer wesentlich weltlicheren und direkteren Form aufgezeigt werden. Dieser Übergang, welcher als entscheidende Phase im Aufkommen von

Summary

After briefly considering the various forms and degrees of social differentiation that may be included in a generic concept of “inequality”, the type of “unequal social relations” will be outlined. The paper focuses on the potential of certain social differences to evolve into real socio-economic disparities and forms of permanent political authority, looking both at some specific types of social conditions which lie at the root of those inequalities and at the different conditions and requirements of subsistence economies in different environments.

The next step is an attempt to analyse the nature of the first unequal and hierarchical social relations in Middle Eastern societies by identifying their economic and/or political bases, with particular reference to the Mesopotamian and peri-Mesopotamian world in the 4th 4^{\text {th }} millennium BCB C. This region shows very interesting examples of the transformation from ranked to truly hierarchical societies, based on a growing centralisation of primary resources and labour, and also offers relevant data for the study of the dynamics of change that led to the formation of early state societies.

The paper analyses the historical roots of the changes that occurred in southern Mesopotamia, from forms of hierarchical kinship ties, recognisable in the Ubaid period ( 5th 5^{\text {th }} millennium BCB C ), to the establishment of unequal economic and political relations in the Late Uruk phases. Such changes resulted in the formation of strong centralised power systems. Since inequality involves subordinate relations, it goes hand in hand with the rise of “power” and differentiated access to resources; a process which also took place in other regions in northern Mesopotamia and south-eastern Anatolia, which are comparatively analysed.

Finally, the case of Arslantepe, in the Upper Euphrates region, is presented in detail, as a meaningful example of the transition from prestige to power and from the use of religious/ideological consensus in public ceremonial practices to the exercise of power in more secular and direct forms, seen here in a very precocious example of a fully fledged palace dated to the end of the 4th 4^{\text {th }} millennium BCB C. This transition is seen as a crucial stage in the rise of the state and the consolidation of unequal socio-political and economic relations.

But the centralised system at Arslantepe, albeit very powerful, probably did not have the solid foundation for a differentiated and hierarchical system of social and economic relations that only an urban society can guarantee. It therefore collapsed as soon as it was born.

Staatsgebilden sowie in der Konsolidierung von ungleichen soziopolitischen und wirtschaftlichen Beziehungsnetzen gelten darf, lässt sich anhand des frühen, jedoch voll ausgebildeten Palasts aus dem ausgehenden 4.Jt. v.Chr. beispielhaft aufzeigen.

Während das zentralisierte System von Arslantepe jedoch über große Macht verfügte, fehlte ihm wohl dennoch die solide Grundlage, die für ein differenziertes und hierarchisch strukturiertes System von sozialen und wirtschaftlichen Beziehungen notwendig und nur in einem urbanen gesellschaftlichen Umfeld gewährleistet ist. Deshalb brach dieses System schon bald nach seiner Entstehung wieder zusammen.

Introduction

»Inequality« is a concept that can be construed in various ways and can comprise various types of inequality with different features, social implications, and consequences. In many cases, rather than inequalities as such, a society simply has socially recognised »differences«, which increase in number and complexity with the »complexity« of the society. These differences can also take various forms and degrees, in some cases bringing with them the enjoyment of privileges by certain members of the community (Flannery/ Marcus 2012; Price/Feinman 2012). There are differences that are called here »horizontal«, based either on »natural« conditions, such as sex and age or on roles and functions accorded by the community to particular members to fulfil its political and social needs. Examples are the particular status accorded to the elderly, initiated adults, warriors, etc. There are also stronger and more deeply rooted differences that are called here »vertical« (Frangipane 2007), involving high-status positions, usually acquired through the rules of kinship systems. In this latter case, »high-status« individuals, families, or kinship groups are often perceived as having special rights and duties within the community and are invested with social and political functions. These functions can confer privileges, or even preferential access to specific goods, but do not necessarily confer the permanent enjoyment of privileged access to basic resources and social surplus. Though often socially significant, therefore, such privileged positions do not automatically imply the existence of »rich and poor«.

This is not the place to examine all the various types and degrees of social difference and complexity in different kinds of society, or even to go more deeply into the matter of »complexity«, a concept which is of questionable utility if it is not better defined. The potential of certain social differences to evolve into real socio-economic disparities and forms of permanent political authority depends on the features and social roots of those inequalities, as well as on the different structures and needs of the subsistence economies to which those differences in social relations are usually related. The paper will focus on a few Middle Eastern cases, in which certain socially significant differentiations bore within them the seeds of change and demonstrated the potential to develop into hierarchical and unequal economic and political relations.

The article starts by examining the historical roots of the changes that occurred in Mesopotamia in the course of the 4th 4^{\text {th }} millennium BC, which probably are to be found in the societies of the 6th −5th 6^{\text {th }}-5^{\text {th }} millennium BC. In the southern regions of the Euphrates and Tigris alluvium, archaeological evidence suggests the existence, since the first occupation of this area, of forms of »vertical« social differences, which, while not initially creating all-out inequalities in terms of economic privileges, were probably linked to a status acquired by birth, perhaps on the basis of kinship rules (Frangipane 2007).

Pyramidal descent lines, such as primogeniture, and other systems of hierarchical descent are usually traced back to a common ancestor, real or presumed, often considered to have godlike status - a well-known typical case being the »conical clan« described by P. Kirchhoff (1959) - and may lead to the establishment of hierarchically ordered »corporate groups«, whose prerogatives and privileges vary from case to case. Sometimes, indeed often, the higher-status positions in societies of this kind tend to coincide with the political and religious leadership of the community. And it is precisely when this linkage is established between a socially stable pre-eminent position and a dominant political role that probably the foundations are laid for embarking on the process of gradual hierarchisation of society, the formation of elites and the widening of the gap between the elites and the rest of the population. The perception of differences in status as »natural« makes it easier for dominant figures to gain social acceptance, especially when their tasks and prerogatives, though perceived as »useful« for the operation of the society, imply some degree of coercive pressure.

We must certainly not ignore the issue of why kinship systems of this kind developed only in some cases and not in others. The hypothesis is that their emergence was due to challenges posed by particular economic and environmental circumstances which encouraged the establishment of hierarchically structured societies that were better able to tackle them. These same circumstances may have included resources of varying quality and potential, producing an additional increase in inequality. This is a complex issue, however, and one which again cannot be thoroughly addressed here. What is interesting is that stable and socially accepted differences in the social order usually bear within them the seeds of effective inequality.

Fig. 1 Map showing the sites mentioned in the text.

Abb. 1 Kurtierung der im Text erwähnten Fundstellen.

Mesopotamian societies in the 5th 5^{\text {th }} millennium BC

It is well known that Mesopotamia provides some very ancient archaeological evidence of the control, management, and administration of the primary economy, and equally important evidence of the use of ideological instruments - hinging on cultic/ceremonial aspects - to manage social consensus. Even though the excavations in Lower Mesopotamia have been very seriously impacted in recent decades by the political situation in countries in the region, significant archaeological data can still be used to study the problems regarding the structure of the societies in the 5th 5^{\text {th }} and 4th 4^{\text {th }} millennia BC and the changes that occurred in the course of those millennia towards increasing social inequality and the formation of politically and economically highly centralised and powerful government institutions. In particular, we find evidence of certain dynamics that appear to have led to a gradual concentration of prestige, authority, and economic control in the hands of a few presumably high-ranking individuals.

At the beginning a very short overview of the social foundations of the centralised system of 5th 5^{\text {th }} millennium BC Ubaid society (Henrickson/Thuesen 1989; Carter/Philip 2010) will be given.

Few sites of the Ubaid period have yet been extensively excavated, and the paper will therefore refer to information revealed by old excavations at well-known sites such as Tell Oueili (Huot 1989; Huot 1991) and Tell Abada (Jasim 1989) in southern and central Mesopotamia, and Tepe Gawra in the north (Fig. 1; Tobler 1950; Rothman 2002; Butterlin 2009). One constant feature of these sites is the shape and dimensions of the dwellings, which are tripartite and very large (ranging from about 300 m2300 \mathrm{~m}^{2} in the south to 100−180 m2100-180 \mathrm{~m}^{2} in the centre and north; Fig. 2a-b), indicating that the household units were also of considerable size, possibly extended families. In the only two extensively excavated villages in Mesopotamia, Tell Abada and Tepe Gawra (level XII), ascribed to an Early and Late Ubaid phase respectively, one house in each village exhibited particular features in terms of its larger dimensions and the associated finds (Fig. 2c), which comprised assemblages of administrative tools, such as tokens at Tell Abada and clay sealings and seals at Tepe Gawra. Another special feature of these houses is the concentration of child burials - present in far fewer numbers under the floors of other dwellings -, whose high numbers may perhaps indicate that the chief or leader and his family were assigned the role of symbolically representing the

Fig. 2a-e Mesopotamian tripartite houses and «temples» from the Ubaid period. a Tepe Gawra, level XV; b Tell Oueili; c Tell Abada; d Tepe Gawra, level XIII; e Eridu, level VII temple.

Abb. 2a-e Dreiteilige Häuser und »Tempel» aus der Obed-Zeit in Mesopotamien. Tepe Gawra, Level XV; b Tell Oueili; c Tell Abada; d Tepe Gawra, Level XIII; e Eridu, Level VII Tempel.

entire community. The combination of all these lines of evidence may suggest that Ubaid society tended towards a conical structure based on large families or lineages, a structure that tends to be confirmed by what we know of the later Mesopotamian society from the Early Dynastic texts 1{ }^{1}.

It is therefore not surprising to find that the layout of the earliest temples from the Ubaid period, both at Eridu, south Mesopotamia (Safar et al. 1981), and Tepe Gawra (Tobler 1950), closely recall, in general terms, the plan of the tripartite houses. Even their size is not significantly larger than that of the larger dwellings, albeit showing a different use of space and exhibiting special architectural features, such as walls decorated with multiple recessed niches and buttresses and, in the case of Eridu temples, a raised platform underneath (Fig. 2d-e). These special buildings were probably the places in which ceremonial and other public events were managed by the same high-ranking persons who performed the role of leaders of their communities. In these buildings, which presumably symbolically represented the »public spaces« of the paramount chiefs, and/or perhaps the »houses of the gods« of which they were the »representatives«, these leaders were quite probably engaged in ceremonial activities connected with food distribution. We have indeed only very partial clues in this respect, namely the well-known presence of a concentration of fish-bones in the temple of level VI at Eridu, which recall the well-known large offerings of fish to the temples in later periods (Adams 1966, 50). Fish were probably stored and/or distributed in ceremonies or ritual feastings in the same building. Another indirect clue are the numerous cretulae (clay sealings) which were found discarded after use in a pit in an open area near the temple of level XIII at Tepe Gawra. They were almost certainly for sealing containers and therefore related to transactions concerning stored food, and may evidence administrative control over ceremonial redistribution.

There are insufficient data on the storage systems of the Ubaid period, and we have therefore no indication of the possible existence of accumulated goods and, if such accumulations did exist, the form in which their distribution would have taken place within the 5th 5^{\text {th }} millennium BC society. However, the presence of seals and sealings in the tripartite houses of the Late Ubaid settlements in the north (Tepe Gawra level XII and Değirmentepe) 2{ }^{2}, may suggest a diverse capacity for food hoarding and management acquired by different households at the end of the period. Though seals and sealings were scattered in various parts of the settlements, sealings are mainly concentrated in one or two buildings: in the largest »white room« house at Tepe Gawra XII and in two adjacent houses in the south-western part of the Değirmentepe village, where there were 111 and 203 sealings respectively out of a total of 449 found at the site (Esin 1994). The Ubaid society therefore appears to have been organised on the basis of extended households (Pollock 1999), which may perhaps even have competed with one another, and, although the funerary rituals do not demonstrate any clear intention to provide symbolic representation of social differences (Stein 1994), the organisation of the

settlements, and the domestic and public/ceremonial architecture may reveal possible embryonic forms of social hierarchies from which leaders emerged, performing socio-political and religious functions. It is possible that forms of initial management of food circulation were embedded in the public ceremonial practices and began to extend to the household economy at the very end of the period.

The centralisation of functions, as well as the whole structure based on large families with emergent social hierarchies, may have been favoured by the particular conditions of the Lower Mesopotamian environment. The area had a high and varied production potential, with vast arable lands for cereals, zones for horticulture, pasture zones, and extended coasts for fishing, but also suffered from a high risk of soil salinisation, due to aridity and high temperatures, as well as being prone to flooding in the southernmost areas of the Tigris and Euphrates delta, which was full of small streams and canals (Adams 1981). This environment, as Adams stated many years ago, may have created the conditions for a wide range of different specialised subsistence productions in various ecological zones within a relatively restricted area, thus stimulating the mediating role of emergent central institutions, which seem to have managed food circulation through forms of ritualised exchange in ceremonial - perhaps »religious« - environments (Adams 1966, 47-50). Hierarchical kinship rules must have been very much in keeping with this system, according to high-rank persons rights connected with the administration of these central institutions: the right to collect and accumulate goods and services in order to carry out the redistribution, as well as the right to perform the social and political practices associated with this redistribution. This capacity must have been linked to their prestige and social rank and, though perhaps also ideologically perceived as being employed for the benefit of the whole society, must have soon become an instrument for increasing the income of these leaders at the expense of the rest of the population. The construction of temples or other monumental ceremonial places, attested in Mesopotamia since the Ubaid period, is to be seen both as the creation of public spaces for the ritualised redistribution of foodstuffs in codified social practices and the expression of the initial capacity of the leaders to control and centralise resources and labour, albeit to a limited extent.

However, while the monumental character of the temples and the presence of special houses reveal the prestige, and perhaps leadership, of elite personages from the beginning of the Ubaid period, and while these leaders were probably also vested with ceremonially performed economic tasks, there is no clear evidence of any real wealth accumulation or direct management of staple production until the very end of the period. It was in the second half of the 5th 5^{\text {th }} millennium BC (Final Ubaid and Late Chalcolithic 1; Rothman 2001, 5-9 Tab. 1,1) that, particularly in the north, mass production of bowls for the large-scale distribution of food (the so-called coba bowls) and administrative procedures based on sealing food containers to control the circulation of food staples developed for the first time, both in public contexts

- 1 Diakonoff 1969; Gelb 1979; Gelb et al. 1991; Pollock 1999.

2 Tobler 1950; Esin 1994; Rothman 2002; Gurdil 2010. ↩︎

and amongst private elites. The concentration of seals and sealings, particularly that of sealings, in the larger and paramount house of level XII at Tepe Gawra (the so-called white room building) clearly suggests a new role for the community leader and his family in managing resources, involving special economic prerogatives and privileges.

New developments in 4th 4^{\text {th }} millennium BC Greater Mesopotamia

Throughout the first half of the 4th 4^{\text {th }} millennium BC (Late Chalcolithic 2-4), the social and religious status vested in high-ranking figures as a way of legitimising their function of economic coordination appears to have led to a constant increase in their prestige and, through this, to their everincreasing capacity to manage large sectors of the production of staple goods and consequently to control the labour force which produced them. Redistribution continued to be mainly practiced in ritual environments, though it was carried out on an increasingly massive scale, having probably become the mechanism for remunerating the labour of a growing number of individuals. A feedback circuit was thus established:

Prestige of high status social groups →\rightarrow allocation to them of the management of food circulation through ritualised redistribution →\rightarrow accumulation of staple goods in the hands of these high-ranking persons who played the role of leaders →\rightarrow growing number of people who paid their service and work to these leaders →\rightarrow large scale redistribution to remunerate them →\rightarrow heightened prestige →\rightarrow increased accumulation of goods and means of production (basically land and livestock) →\rightarrow impoverishment of part of the population →\rightarrow more provision of labour →\rightarrow expanded economic control of the leaders over primary production (and the means of production) →\rightarrow political and economic power. The ratio of accumulated and redistributed goods became crucial 3{ }^{3}. Food redistribution at any rate became the linchpin of the political economy implemented by the nascent elites and the instrument for exercising control over the life of the people.

In the 4th 4^{\text {th }} millennium BC we see temple areas of increasing complexity, vastness, and monumentality, with massive evidence of redistribution and economic-administrative activities. It is sufficient to mention the Eye Temple at Tell Brak, preceded by other monumental buildings of which we only know a little 4{ }^{4}, the temple area of level VIII at Tepe Gawra in northern Mesopotamia (Tobler 1950; Rothman 2002; Butterlin 2009), Temple C at Arslantepe on the Anatolian Upper Euphrates (Frangipane 2000; Frangipane 2003; Frangipane 2010a, 31-36), as well as the sparse clues of a huge temple area at Uruk-Warka in the Eanna zone, which clearly developed later on in the magnificent and well-known sacred area, at the end of the 4th 4^{\text {th }} millennium BC (Eichmann 2007; Butterlin 2012). Public areas were not only larger than before, but they were also more complex, usually consisting of several buildings, which were presumably intended for

different functions. The change seen at Tepe Gawra is interesting in this respect: there was apparently no longer any dwelling in Gawra VIII and the small site itself became a ceremonial-administrative centre (Tobler 1950; Frangipane 2009).

All these public areas still had ceremonial/religious connotations, demonstrating that the exercise of power, which was by now certainly founded on the capacity for economic intervention and control of production activities, was still being mediated by the ideological/cultic medium traditionally used to guarantee social consensus and maintain the investiture of power by society. Even though there were not yet any clear signs of the centralised storage of goods in Late Chalcolithic 2-4 (although perhaps there was some evidence at Gawra VIIIA), the massive presence of mass-produced bowls and seals and sealings in the public areas provides evidence that a radical change had occurred and not only that the public and economic functions of the community leaders had been reinforced but that their prerogatives and capacity to interfere with the productive activities of the population had also changed, while access to resources by different members of the community was becoming increasingly unequal.

It is interesting to note that though substantial inequalities were certainly present by this period, no particular attention was yet paid to their ideological and symbolic expression in the funerary ritual, judging from the almost total absence of evidence from burials throughout the whole of the Uruk world.

Since the political economy of these 4th 4^{\text {th }} millennium BC Mesopotamian societies revolved essentially around staple goods, and commensality practices increasingly became the institutional means of feeding and controlling the labour force, the political power of the high-status individuals leading the community also became economic power. As time went on, these individuals were able to interfere more penetratingly in the lives of the people, giving rise to a deeply rooted power system, which tended to expand its sphere of action to control ever more resources and people. While the main centres tended to expand »their« territory ever more widely, they may at the same time have interacted systematically with the surrounding regions, thus creating a network of relations and promoting the dissemination of both cultural and behavioural models and economic and political systems. It must have been this process, rather than the pressure of trading colonies (Algazé 1993; Stein 2005), which caused the extraordinary widening of »cultural areas« and related political and economic systems in the course of the Middle and Late Uruk period (Late Chalcolithic 4-5) and was thus the main reason for the cultural »unification« of the Uruk world.

In the last centuries of the 4th 4^{\text {th }} millennium BC (Late Chalcolithic 5), the process of increasing social and economic differentiation seems to have had its foundation and legitimation in the growing power of the ruling classes, which was in turn based on a growing centralisation of resources

[1]4 Oates/Oates 1997; Oates 2002; McMahon/ Oates 2007; Oates 2012.

- 3 R. Bernbeck (1994) presented an interesting analysis of the quantities of redistributed products and the percentage of the popula-

tion that received redistributed goods in two different types of societies: »big men societies« and »complex chiefdoms«. ↩︎

Fig. 3 The Arslantepe mound in the Malatya plain, eastern Turkey.

Abb. 3 Der Arslantepe-Hügel in der Malatya-Ebene, Osttürkei.

in their hands. Economic power, in these formative phases, therefore coincided with political power, and the »richest" individuals seem to have been those persons or groups who were vested with central authority. But a system of this kind, as it grew, would have entailed the delegation of power and functions to a growing number of individuals responsible for exercising administrative control over increasingly numerous social entities and vast areas in the name of the central ruler.

By the end of the 4th 4^{\text {th }} millennium BC , this power system developed into fully fledged early state institutions, with increasingly numerous and well-structured social categories and with the birth of a real class of bureaucrats.

The process of economic and political centralisation and the birth of »institutional« inequality: the case of Arslantepe, at the periphery of the Mesopotamian world

The excavations, conducted over many years at ArslantepeMalatya in eastern Turkey (cf. Fig. 1; Fig. 3), have uncovered many crucial aspects of this process, culminating here in the establishment of an early state system, in which the economic and political power of the ruling elite was consolidated and

their authority was expressed and exercised in a non-religious and explicitly »secular« way, marking a new era.

A similar transformation of centralised leadership into a form of early state system, albeit in more or less embryonic form as yet, took place all over the Mesopotamian world at the end of the 4th 4^{\text {th }} millennium BC. In all societies of Greater Mesopotamia, authority began to be exercised by using more effective instruments of political and administrative control, as well as probably a stronger means of coercion. The sophisticated metal weapons discovered in the public buildings at Arslantepe (Fig. 4b-c; Frangipane/Palmieri 1983, 394-407; Di Necera 2010) and the images of prisoners prostrated in front of a codified representation of the ruler - the so-called king-priest - in the Uruk-Warka glyptics (Fig. 4a; Boehmer 1999) are both signs of a more explicit display of the use of force. Moreover, the process of the institutionalisation and centralisation of political and economic leadership went hand in hand with an advanced urbanisation process in Lower Mesopotamia and the Khabour, and urbanisation, in all its complexity and proliferation of tasks, social categories, specialised sectors, and administrative roles, must have played a great part in contributing to the structural transformation of society into a more complex and hierarchical system of relations (Liverani 1998; Algaze 2008). The maturity of the diversified structure of Lower Mesopotamian society, organised into numerous productive categories, and the control exercised by the central authorities over many of these sectors are also clearly evidenced by the pictographic texts from Uruk IVa (Nissen 1986; Nissen et al. 1993).

However, the process of the secularisation of power and the way it was exercised was not yet clearly recognisable in the public areas of the Mesopotamian sites, since these were still either temples or other forms of sacred area, and the character of the performances that took place there still seems to have been, at least formally, predominantly ideological/religious. This is evidenced by the type of public architecture, which comprised imposing, distinct, isolated and usually tripartite buildings, and by the iconography of power expressed in glyptics and other forms of art, where scenes depicting the »temple« (or the »god/goddess« as in the case of the famous alabaster vase from Uruk; SchmandtBesserat 2007, 41-46) and »offerings« largely prevail.

In contrast, the so-called palatial complex from the end of the 4th 4^{\text {th }} millennium BC at Arslantepe, and in particular its northern part, brought to light very recently in the 2014 and 2015 campaigns, provides unequivocal evidence of the secularisation of the exercise and expression of authority and power, testifying to a change, in this Anatolian centre, of which there is at present no evidence elsewhere at such an early period (or at least none so explicitly manifested). These recent findings completed the picture already shown by the great deal of evidence of sophisticated and complex economic-administrative organisation brought to light in earlier campaigns, making ever clearer the elaborate and explicitly diversified functionality of the public spaces in this monumental complex (Frangipane 2010a; Frangipane 2012). They further stress the far-reaching and rapid change that occur-

Fig. 4a-c a Seal design from Uruk-Warka depicting prisoners in front of the «king-priest»; b-c copper spearheads and swords from the palace complex at Arslantepe. No scale

Abb. 4a-c a Siegelmotiv aus Uruk-Warka mit Gefangenen, die dem »Priesterkönig« vorgefahrt werden; b-c Speerspitzen sowie Schwerter aus Kupfer aus dem Palastkomplex von Arslantepe. o.M.

red at the site from the period of the previous ceremonial/ cultic area of the first half of the 4th 4^{\text {th }} millennium BC5\mathrm{BC}^{5}.

Ritual redistribution in Period VII (Late Chalcolithic 3-4)

The first half of the 4th 4^{\text {th }} millennium BC at Arslantepe (Period VII in the site sequence) was marked, as was the rest of the Mesopotamian world, by the emergence of elites, probably with the role of governing their communities, which was exercised and expressed symbolically through the performance of ritual practices in monumental buildings that we presume to have been cultic in character. The question posed by some scholars as to whether the Mesopotamian temples in the protourban phases were actually »temples« in the proper sense of the term is, to my mind, not so relevant, because at all events they were places in which collective practices were performed by preeminent social figures (either chiefs or priests or chief/ priests) in a ritualised and ceremonial manner, through which their prestige and social acceptance were established. Those rituals also entailed performing economically significant acts, such as food redistribution, often accompanied by the administrative control of withdrawals.

Clear evidence of all this is attested at Arslantepe. Monumental buildings, with stout walls, painted plaster and decorative mudbrick columns, had been built on the top of the mound and were probably the residences of the elites (Fig. 5a-b; Frangipane 1993). The northern edge of the tell, where a small area had been excavated in past years, has conversely revealed the presence of small dwellings comprised of one or two rooms, ovens and areas for domestic activities, and burials under the floors (Palmieri 1978). This shows that there was a clear-cut separation within the settlement between the areas used by pre-eminent social categories and areas used by common people (Fig. 6). The different uses to which the areas were put remained unchanged for

Fig. 5a-d (right side) Arslantepe. Period VII (Late Chalcolithic 3-4) elite buildings on the top of the mound. a-b Elite residence with columns of mud and paintings; c plastic and painted decoration collapsed from the walls of Temple D; d plan of Temples C and D.

- 5 Frangipane 2000; D’Anna/Guarino 2010;

Frangipane 2010; Frangipane 2012. ↩︎

Fig. 6 The Arslantepe mound with the Period VII remains brought to light so far (Late Chalcolithic 3-4, 3800-3500 BC).

Abb. 6 Der Arslantepe Hügel mit den bis heute ausgegrabenen Überresten aus Periode VII (Späte Kupferzeit 3-4, 3800-3500 v.Chr.).

several centuries, between 3800 and 3500 BC at least, confirming that social segregation continued to be a stable feature.

By the side of the elite residences and in architectural continuity with them, a ceremonial monumental public area was built. Though seriously damaged, the remains were discovered of a large tripartite building with a huge central hall, Temple C, which stood on an imposing stone base (Fig. 5d). This building was the site of very intensive redistribution practices, evidenced from about a thousand mass-produced bowls (Fig. 7d-e) and numerous clay sealings 6{ }^{6} (Fig. 7a-c). In the 2015 campaign, which has just ended, another building immediately adjacent to Temple C and in perpendicular alignment with it was found, of which only a small part has yet been brought to light, which seems to have been equally large and imposing (cf. Fig. 5d). The walls of this building were decorated with multiple recessed niches and red and black geometrical relief decorations (Fig. 5c), there was a central platform or podium, and it appears to have been another temple (Temple D). The corner stair-room (A1416A961) had been filled with hundreds of bowls and discarded clay sealings (Fig. 7a-b) dumped in successive rubbish layers. These two buildings (Temple C and D) were certainly contemporary with each other, at least in their final use, as is also confirmed by the presence in both of them of sealings bearing the impressions of the same three seals. The southern part of Temple D was destroyed and its eastern area is still to be excavated, but the architectural arrangement of the two buildings seems to suggest the existence of a kind of

sacred area, as used in Mesopotamian environments, above all, for ceremonial practices of food redistribution. The large central halls and the wall painting and decorations inside them, together with the many entrances to the main hall in Temple C and the thousands of bowls both scattered on the floor of this hall and found in large numbers in the side rooms of the same building, where they may have been kept ready to be used (Fig. 7f), all suggest the wide participation of the population in the rites, ceremonies and feasting that took place in these buildings (Helwing 2003; Pollock 2012).

The climax of the concentration of economic and political power in the hands of the Arslantepe elites at the end of the 4th 4^{\text {th }} millennium BC (Period VIA, Late Chalcolithic 5)

Both temples were abandoned around 3500 BC (they are among the few buildings in Arslantepe that were not destroyed by fire) and in the following period, in the final centuries of the 4th 4^{\text {th }} millennium BC , there was a radical change in the power system, although accompanied by substantial developmental continuity. The residences of the elite were rebuilt on the same area on which the previous ones had stood, but they were now linked directly to a new public area which was radically different from the previous one in terms of architectural design and functions, revealing that a far-reaching change had occurred in the way relations between

- 6 Frangipane 2000; Frangipane 2003; Frangi

pane 2010a, 31-36; Frangipane 2012, 20-27. ↩︎

Fig. 7a-f Arslantepe, Period VII. a-c Cretulae (clay sealings) and mass-produced bowls (d-f) from the two temples.

Abb. 7a-f Arslantepe, Periode VII. a-c Cretulae (gessiegelter Ton) und serienproduzierte Schüsseln (d-f) aus den beiden Tempeln.

Fig. 8a-b Arslantepe, Period VIA (Late Chalcolithic 5,3400−5100BC5,3400-5100 \mathrm{BC} ). The corridor leading to the courtyard and “audience building” 37 (a) with walls decorated by paintings in red and black and plastic impressed motives (b). A drainage channel ran under the floor of the corridor carrying rainwater from the courtyard outside the palace.

Abb. 8a-b Arslantepe, Periode VIA (späte Kupferzeit 5, 3400-5100 v.Chr.). Der Korridor zum Innenhof sowie »Audienzgebäude« 37 (a), dessen Wände mit roten und schwarzen Madereien sowie mit plastisch eingedrückten Motiven verziert sind (b). Ein Abwasserkanal führte Regenwasser aus dem Innenhof des Palastes unter dem Boden des Korridors aus dem Palast.

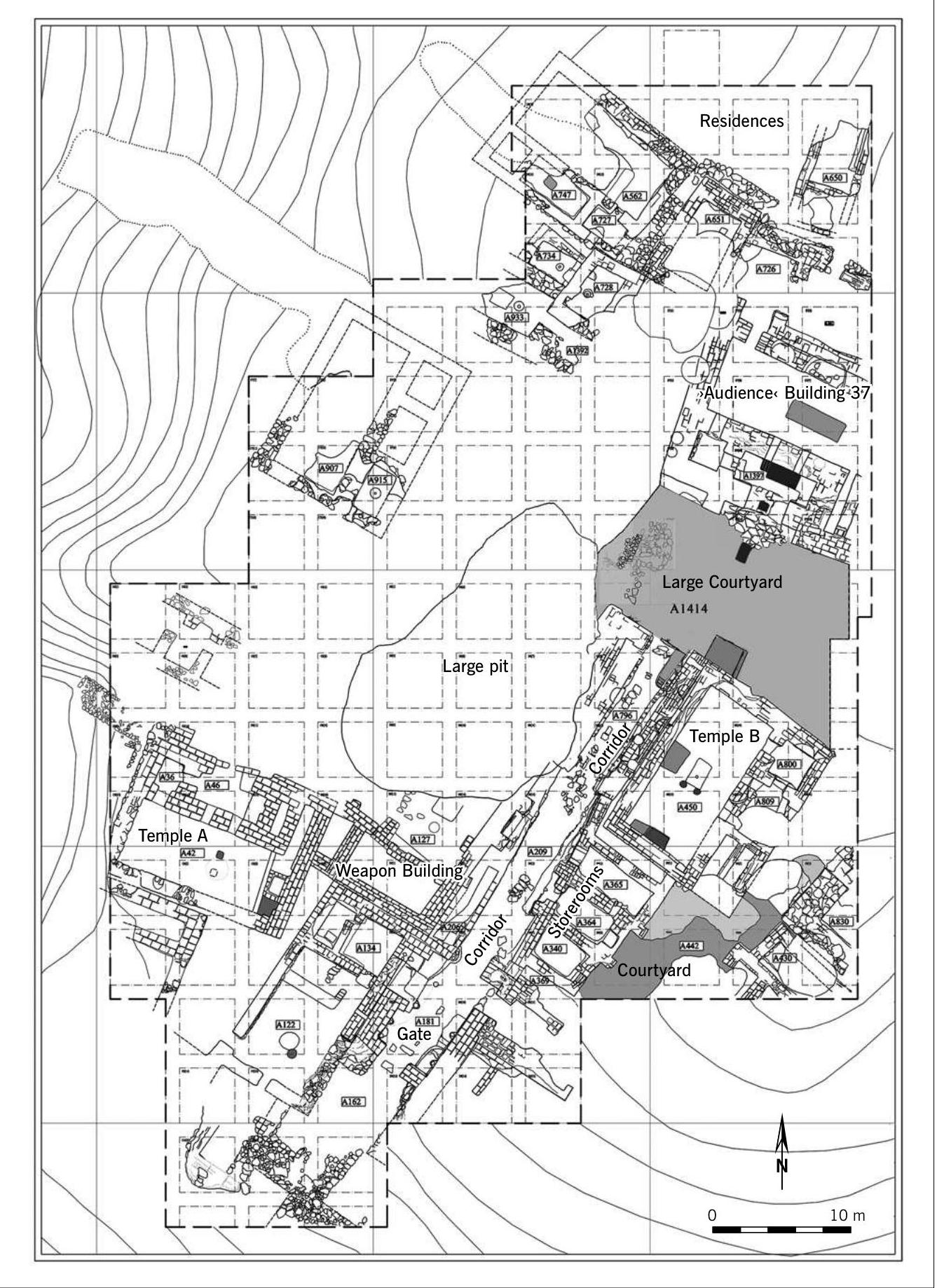

the elites and the population took place. An entrance corridor (A796) decorated with stamped lozenge motifs and wall paintings (Fig. 8) led into a large courtyard, where visitors would have found themselves faced by a building of monumental splendour (Fig. 9 and 10). This very imposing building, which now seems to have been the core of this new public area, was much smaller in size than the previous temples from Period VII and does not show any cultic or religious features. The contact point with the public was a small room (A1397) occupied entirely by a high platform or base, with three steps leading up it, on which the remains of small pieces of charred juniper wood have been found, very likely the remains of a mobile structure, possibly a chair or »throne«. The public did not go further into the building, because access to the internal part, comprising a large hall (A1358) with a long low platform equipped with a fireplace and possibly a table, could only be reached by passing through a small side room (A1401; Fig. 9b). The entry to the internal hall must therefore have been restricted to authorised persons. And this room communicated with the residences

to the north, linking the public and private areas of the complex.

Facing the platform in the small room A1397, in the area where a wide opening and a stone ramp or staircase linked the room with the courtyard, there were also two small raised clay bases, built perfectly in line with each other and with the platform, which must have marked the places where outsiders had to stop when presenting themselves to the person in authority (Fig. 9a; cf. Fig. 10). It may therefore have been the place in which the ruler addressed the public and held audiences with people gathered in the wide courtyard, in a ceremonial environment without any cultic or religious connotations.

On the south-eastern edge of the courtyard there was a building used for cultic purposes (Temple B), whose floor plan was almost identical to the “audience building” (Building 37), but which was less monumental and had internal features (altars and podiums with a central hearth) and materials providing evidence of cultic practices (cf. Fig. 10). In this case, too, access to the cult room, unlike the situation

Fig. 9a-b Arslantepe, period VIA. The «audience building» 37. a View from the south; b view from the east.

Abb. 9a-b Arslantepe, Periode VIA. Das «Audienzgebäude» 37. a Blick von Süden; b Blick von Osten.

Fig. 10 Arslantepe, period VIA. Plan of the oldest part of the palace and the elite residences.

Abb. 10 Arslantepe, Periode VIA. Plan des ältesten Teils des Palasts und der repräsentativen Wohngebäude.

in the temples from the previous period, was limited and restricted, and the consumption of meals seems to have been reserved only for a few (D’Anna 2010; Bartosiewicz 2010). We can therefore conclude that cult practices were now reserved for elites, perhaps the ruling class, the majority of the population being excluded.

Although relations between the chiefs and the divinities must still have been the main rationale for their legitimacy and the stability of their power, as well as the basis of their social acceptance, the ways in which their authority was

exercised and the public practices linked to it seem to have radically changed at Arslantepe by this time. Power was no longer exercised through cultic practices, but directly, and in a “secular” manner. The place in which authority was exercised and presented to the eyes of the people was no longer a sacred place, but a broad space where people gathered and the leader or sovereign appeared publicly and acted directly without any mediation.

But what were the dynamics and the reasons for this change? What were the changes, if any, in the way the economy was managed and in the relationship between privileged social status and political power?

The evidence found at Arslantepe suggests that, as in the rest of the Mesopotamian world, the basic economic system and the political economy of the ruling elite did not change fundamentally and continued to hinge on the management of staple commodities - D’Altroy and Earle’s “staple finance” -7 , being actually strengthened to the point that they no longer needed any ideological forms of mediation outside the system itself. The ideology of power, rather than being expressed in the sacred sphere, now used symbolic elements and artistic expressions referring to the central role of agricultural production and management (Fig. 11; Frangipane 2010; D’Anna 2015), underlining the fact that subsistence goods must have been central to the very concept of “wealth”. Staple goods, mostly foodstuffs, were, however, perishable and their value as goods could only be exploited by re-investing them. The accumulation of wealth was therefore essentially a matter of accumulating the means of production and controlling the labour force to make them productive. Redistribution was the way in which these goods were re-invested, by feeding the labour force and thereby enabling them to continue producing more. In this early centralised society at Arslantepe, as apparently in the rest of the Mesopotamian world, no large storage facilities have been found capable of holding huge quantities of goods, but only small rooms that were continually filled and emptied, from which redistribution was carried out. The development of sophisticated methods of administrative control over the circulation of these commodities was perfectly consistent with this system (Frangipane et al. 2007).

Many other sectors were subsequently added to the original core of the VIA public area, including a set of store rooms, another courtyard, other official buildings, as well as a monumental entry gate and another small temple (Temple A), making the whole complex a real multifunctional and unitary architectural assemblage (Fig. 12-13). The visibility of the main platform with the hypothesised ruler’s chair in the “audience building” continued to be maintained in the course of the various building additions and it remained the main focus of the view revealed to anyone who entered the gate and the corridor. This huge monumental complex, which occupies more than 3500 m23500 \mathrm{~m}^{2} in the parts brought to light so far, can be considered, probably, a fully fledged “palace”, comprising a planned series of buildings with different but correlated public functions, all architecturally

- 7 Polanyi 1944; D’Altroy/Earle 1985; Balossi

Restelli et al. 2010; Frangipane 2010b;

Palumbi 2010. ↩︎

Fig. 11a-d Arslantepe, period VIA. a-b Images symbolically referring to agricultural practices from seal impressions; c the well-known Arslantepe seal design with a high ranking personage (the leader?) on a sledge cart, probably a threshing tribulum; d the wall painting in the corridor showing two oxen pulling a cart or a plough driven by a charioteer.

Abb. II Arslantepe, Periode VIA. a-c Symbolische Darstellungen landwirtschaftlicher Tätigkeiten von Siegelabdrücken; c das bekannte Siegelmotiv aus Arslantepe, welches eine hochgestellte Persönlichkeit (den Machthaber?) auf einem Dreschschlitten, wohl einem Dresch-Tribulum, zeigt; d Wandmalerei aus dem Korridor mit einem von zwei Ochsen gezogenen Karren oder Pflug und einem Wagenlenker.

Fig. 12 The Arslantepe Palace with the new added sectors seen from the south.

Abb. 12 Südansicht des Palasts von Arslantepe mit den neu hinzugekommenen Flächen.

linked and largely inter-communicating, connected to the elite residences through the most important official building and place of contact with the public.

The palace stores now formed the heart of the elites’ economic activity. Dozens of food containers and hundreds of mass produced bowls, found together with 130 clay sealings in the smallest room, the distribution store, provide evidence that redistribution practices increased considerably, losing their ceremonial connotations and probably becoming regular meals given to numerous individuals in areas set aside for this purpose. Thousands of clay sealings bearing the impressions of more than 220 different seals found in various parts of the palace reveal the existence of a sophisticated administrative system, and an articulated class of bureaucrats with differentiated and hierarchically organised functions (Fig. 14; Frangipane et al. 2007).

Taking all this evidence together, the ceremonial redistribution practices performed, perhaps less frequently, in the first half of the 4th 4^{\text {th }} millennium BC , seem now to have been replaced by regular redistributions to hundreds of individ-

uals visiting the palace to receive remuneration for their work. These people did not take part any more in any collective rituals and inclusive social practices (the temples were small and »closed« to the majority of the population), and they were probably only allowed to go into the »place of power« (the main courtyard and »throne room«) on certain occasions, during which they must have been received in secular ceremonies stressing their subordinate position. An encroaching »exclusion« process was taking place to gradually deepen social inequalities and exponentially widen the gap between social categories.

Exclusion was also implemented at Arslantepe by »expelling" most of the people from the site, which by the end of the 4th 4^{\text {th }} millennium BC seems to have been considerably reduced in size from what it had been in the previous period, while the majority of the population must have lived scattered around in the surrounding countryside. This process was therefore the opposite of what was happening in the Mesopotamian plains, where the increasing centralisation of power was accompanied by intense urbanisation 8{ }^{8}. Here,

Fig. 13 Floor plan of the Arslantepe Palace showing all sectors so far brought to light.

Abb. 13 Grundriss des Palasts von Arslantepe mit allen bisher ergrabenen Flächen.

Fig. 14a-i Administration in the Arslantepe Palace: a-c clay sealings; d-e, g-h reconstruction from the impressions of some of the sealed containers; f reconstruction of door-peg sealing type; i mass-produced wheel-made bowls.

Abb. 14a-i. Die Verwaltung im Palast von Arslantepe: a-c Gesiegelter Ton; d-e, g-h Rekonstruktion aufgrund der Abdrücke auf einigen der versiegelten Behälter; ff Rekonstruktion eines Türstiftsiegels; i serienprodazierte, scheibengedrehte Schüsseln.

the growth of a very powerful and well-organised early state system was not bound up with a parallel process of urbanisation but, on the contrary, made Arslantepe a powerful poli-tical-administrative centre probably inhabited only by the pre-eminent social categories which ruled over the community (Frangipane 2009).

This must have increased the distance between the elites, probably living at the site and governing the community through the use of efficacious administrative tools, capable of expanding the exercise of power by delegating authority to intermediate social figures (the bureaucrats), and the rest of the population, who probably continued to conduct their primary production activity according to their traditional way of life. This can also be assumed from looking at the events that followed the destruction of the palace.

The collapse of a centralised and unequal system

This peculiar and precocious development came rapidly to an end at Arslantepe around 3000 BC, ending in the destruction by fire of the palace and in a real collapse of the entire system.

It is very possible that the deep differences and fully unequal relations established in Arslantepe society at the end of the 4th 4^{\text {th }} millennium BC were not securely enough based on the sort of deeply rooted, complex and fully accepted social hierarchy which in other regions was usually supported and stabilised by urban contexts. The central authorities, as is demonstrated by the archaeological data, used their power to centralise staple resources and probably accumulate means of primary production (as is suggested by the regular food redistribution practices, very probably aimed at compensating work in the palace), to the point that an increasing number of persons became subjugated. In this situation, where a rapid verticalisation of society had taken place in the absence of well-based social roots of inequality, the explicit and secular display of strongly unequal power relations, which in other contexts did not take place until the hierarchical systems had reached full maturity, very probably contributed to social conflicts and instability, highlighting the imposed nature of this power, creating resistance to it, and resulting in rebellions and the failure of the entire organisation (Frangipane 2012a).

Bibliography

Adams 1966

R. M. Adams, The evolution of urban society. Early Mesopotamia and prehispanic Mexico (Chicago 1966).

Adams 1981

R. M. Adams, Heartland of cities. Surveys of ancient settlement and land use on the central floodplain of the Euphrates (Chicago 1981).

Algaze 1993

G. Algaze, The Uruk world system. The dynamics of expansion of early Mesopotamian civilization (Chicago 1993).

Algaze 2008

G. Algaze, Ancient Mesopotamia at the dawn of civilization. The evolution of an urban landscape (Chicago 2008).

Balosti Restelli et al. 2010

F. Balosti Restelli/L. Sadori/A. Masi, Agriculture at Arslantepe at the end of the IV millennium BC. Did the centralised political institutions have an influence on farming practices? In: M. Frangipane (ed.), Economic centralisation in formative states. The archaeological reconstruction of the economic system in 4th 4^{\text {th }} millennium Arslantepe. Stud. Preist. Orient. 3 (Rome 2010) 103-117.

Bartosiewicz 2010

L. Bartosiewicz, Herding in period VIA. Developments and changes from period VII. In: M. Frangipane (ed.), Economic centralisation in formative states. The archaeological reconstruction of the economic system in 4th 4^{\text {th }} millennium Arslantepe. Stud. Preist. Orient. 3 (Rome 2010) 119-148.

Bernbeck 1994

R. Bernbeck, Die Auflösung der häuslichen Produktionsweise: das Beispiel Mesopotamiens. Berliner Beitr. zum Vorderen Orient 14 (Berlin 1994).

Boehmer 1999

R. M. Boehmer, Uruk, Früheste Siegelabrol lungen. Ausgrabungen in Uruk-Warka, Endberichte 24 (Mainz 1999).

Butterlin 2009

P. Butterlin (ed.), A propos de Tepe Gawra, le monde proto-urbain de Mésopotamie. Subartu 23 (Turnhout 2009).

Butterlin 2012

P. Butterlin, Les caractéristiques de l’espace monumental dans le monde Urukéen: de la métropole aux colonies. Origini 34, 2012, 179-200.

Carter/Philip 2010

R. A. Carter/G. Philip (eds.), Beyond the Ubaid. Stud. in Ancient Orient. Civilization 63 (Chicago 2010).

D’Altroy/Exile 1985

T. N. D’Altroy/T. K. Exile, Staple finance, wealth finance, and storage in the Inka political economy. Current Anthr. 26,2, 1985, 187-206.

D’Anna 2010

M. B. D’Anna, The ceramic containers of period VI A. Food control at the time of centralisation. In: M. Frangipane (ed.), Economic centralisation in formative states. The archaeological reconstruction of the economic system in 4th 4^{\text {th }} millennium Arslantepe. Stud. Preist. Orient. 3 (Rome 2010) 176-191.

D’Anna 2015

M. B. D’Anna, A material perspective on food politics in a non-urban center. The case of Arslantepe Period VIA (LCS). Origini 37, 2015, 56-66.

D’Anna/ Guarino 2010

M. B. D’Anna/ F. Guarino, Continuity and changes in the elite food management during the 4th 4^{\text {th }} millennium BC. Arslantepe Period VII and VI A. A comparison. In: M. Frangipane

(ed.), Economic centralisation in formative states. The archaeological reconstruction of the economic system in 4th 4^{\text {th }} millennium Arslantepe. Stud. Preist. Orient. 3 (Rome 2010) 193-204.

Diakonoff 1969

I. Diakonoff (ed.), Ancient Mesopotamia. socio-economic history (Moscow 1969).

Di Nocera 2010

G. M. Di Nocera, Metals and metallurgy. Their place in the Arslantepe society between the end of the 4th 4^{\text {th }} and beginning of the 3rd 3^{\text {rd }} millennium BC. In: M. Frangipane (ed.), Economic Centralisation in Formative States. The archaeological reconstruction of the economic system in 4th 4^{\text {th }} millennium Arslantepe. Stud. Preist. Orient. 3 (Rome 2010) 255-274.

Eichmann 2007

R. Eichmann, Uruk, Architektur I. Von den Anfängen bis zur frühdynastischen Zeit. Ausgrabungen in Uruk-Warka Endberichte 14 (Rahden/Westf. 2007).

Emberling/McDonald 2003

G. Emberling/H. McDonald, Excavations at Tell Brak 2001-2002. Preliminary report. Iraq 65, 2003, 1-75.

Esin 1994

U. Esin, The functional evidence of seals and sealings of Değirmestepe. In: P. Ferieli/ E. Fiandra/G. G. Fissore/M. Frangipane (eds.), Archives before writing (Rome 1994) 59-81.

Flannery/Marcus 2012

K. V. Flannery/J. Marcus, The creation of inequality. How our prehistoric ancestors set the stage for monarchy, slavery, and empire (Cambridge, MA 2012).

Frangipane 1993

M. Frangipane, Local components in the development of centralized societies in Syro-Anatol-

- Adams 1981; Oates et al. 2007; Di et al. 2011; Wilkinson et al. 2014; Yoffee 2015.

↩︎

- Adams 1981; Oates et al. 2007; Di et al. 2011; Wilkinson et al. 2014; Yoffee 2015.

ian regions. In: M. Frangipane/H. Hauptmann/ M. Liverani/P. Matthiae/M. Mellink (eds.), Between the rivers and over the mountains. Arch. Anatolica et Mesopotamica Alba Palmieri Dedicata (Rome 1993) 133-161.

Frangipane 2000

M. Frangipane, Origini ed evoluzione del sistema centralizzato ad Arslantepe: dal «Tempio» al «Palazzo» nel IV millennio a.C., Isimu 3, 2000, 53-78.

Frangipane 2003

M. Frangipane, Developments in fourth millennium public architecture in the Malatya Plain: From simple tripartite to complex and bipartite pattern. In: M. Ozdoğan/H. Hauptmann/N. Başgelen (eds.), From villages to cities, studies presented to Ufuk Esin

(Istanbul 2003) 147-169.

Frangipane 2007

M. Frangipane, Different types of egalitarian societies and the development of inequality in early Mesopotamia. World Arch. 39,2, 2007, 151-176.

Frangipane 2009

M. Frangipane, Non-urban hierarchical patterns of territorial and political organisation in Northern regions of Greater Mesopotamia: Tepe Gawra and Arslantepe. In: P. Butterlin (ed.), A propos de Tepe Gawra, le monde protourbain de Mésopotamie. Subartu 23 (Brussels 2009) 135-148.

Frangipane 2010

M. Frangipane (ed.), Economic centralisation in formative states. The archaeological reconstruction of the economic system in 4∘mil4^{\circ} \mathrm{mil} 1ennium Arslantepe. Stud. Preist. Orient. 3 (Rome 2010).

Frangipane 2010a

M. Frangipane, Arslantepe. Growth and collapse of an early centralised system: The archaeological evidence. In: M. Frangipane (ed.), Economic centralisation in formative states. The archaeological reconstruction of the economic system in 4∘4^{\circ} millennium Arslantepe. Stud. Preist. Orient. 3 (Rome 2010) 23-42.

Frangipane 2010b

M. Frangipane, The political economy of the early central institutions at Arslantepe. Concluding remarks. In: M. Frangipane (ed.), Economic centralisation in formative states. The archaeological reconstruction of the economic system in 4∘4^{\circ} millennium Arslantepe. Stud. Preist. Orient. 3 (Rome 2010) 289-307.

Frangipane 2012

M. Frangipane, Fourth millennium Arslantepe: the development of a centralised society without urbanisation. Origini 34, 2012, 19-40.

Frangipane 2012a

M. Frangipane, The collapse of the 4∘4^{\circ} millennium centralised system at Arslantepe and the far-reaching changes in 3∘3^{\circ} millennium societies. Origini 34, 2012, 237-260.

Frangipane/Palmieri 1983

M. Frangipane/A. Palmieri (eds.), Perspectives on protourbanization in eastern Anatolia. Arslantepe (Malatya), An Interim Report on 1975 1983 campaigns. Origini 12, special vol. 2, 1983.

Frangipane et al. 2007

M. Frangipane/P. Ferioli/E. Fiandra/R. Laurito/ H. Pittman, Arslantepe Centralae. An Early Centralised Administrative System Before Writing, Arslantepe vol. V (Rome 2007).

Gelb 1979

I. J. Gelb, Household and family in early Mesopotamia. In: E. Lipinski (ed.), State and temple economy in the ancient Near East (Leuven 1979).

Gelb et al. 1991

I. J. Gelb/P. Steinkeller/R. Whiting, Earliest land tenure systems in the Near East. Ancient kudurrus. Orient. Inst. Publ. 104 (Chicago 1991).

Gurdil 2010

B. Gurdil, Exploring social organizational aspects of the Ubaid communities: A case study of Değirmentepe in eastern Turkey. In: R. A. Carter/G. Philip (eds.), Beyond the Ubaid. Stud. Ancient Orient. Civilization 63 (Chicago 2010) 361-375.

Helwing 2003

B. Helwing, Feasts as a social dynamic in prehistoric Western Asia - three case studies from Syria and Anatolia. Paléorient 29,2, 2003, 63-85.

Henrickson/Thuesen 1989

E. F. Henrickson/I. Thuesen (eds.), Upon this foundation: The 'Ubaid reconsidered (Copenhagen 1989).

Huot 1989

J.-L. Huot, Ubaidian villages of Lower Mesopotamia. Permanence and evolution from Ubaid o to Ubaid 4 as seen from Tell el Ouedi. In: E. F. Henrickson/I. Thuesen (eds.), Upon this Foundation. The 'Ubaid reconsidered (Copenhagen 1989) 19-42.

Huot 1991

J.-L. Huot, Ouedi, Travaux de 1985, Mémoire 89 (Paris 1991).

Huot 1996

J.-L. Huot, Ouedi, Travaux de 1987 et 1989 (Paris 1996).

Jasim 1989

S. Jasim, Structure and function in an 'Ubaid village. In: E. F. Henrickson/I. Thuesen (eds.), Upon this foundation. The 'Ubaid reconsidered (Copenhagen 1989) 79-90.

Kirchhoff 1959

P. Kirchhoff, The principles of clanship in human society. In: M. H. Fried (ed.), Readings in anthropology 2 (New York) 260-270.

Liverani 1998

M. Liverani, Uruk, la prima città (Rome, Bari 1998).

McMahon/Oates 2007

A. McMahon/J. Oates, Excavations at Tell Brak 2006-2007. Iraq 69, 2007, 145-171.

Nissen 1986

H. J. Nissen, The archaic texts from Uruk. World Arch. 17,3, 1986, 317-333.

Nissen et al. 1993

H. J. Nissen/P. Damerow/R. K. Englund, Archaic bookkeeping. Early writing and techniques of economic administration in the ancient Near East (Chicago 1993).

Oates/Oates 1997

D. Oates/J. Oates, An open gate. Cities of the fourth millennium BC (Tell Brak 1997). Cambridge Arch. Journal 7,2, 1997, 287-297.

Oates 2002

J. Oates, Tell Brak: The 4th 4^{\text {th }} millennium sequence and its implications. In: N. Postgate (ed.), Artefacts of complexity. Tracking the Uruk in the Near East (Warminster 2002) 111-122.

Oates 2012

J. Oates, Early administration at Arslantepe and Tell Brak (ancient Nagar), Origini 34, 2012, 169-178.

Oates et al. 2007

J. Oates/A. McMahon/P. Karsgaard/S. Al Quntar/ J. Ur, Early Mesopotamian urbanism. A new view from the North. Antiquity 81,313, 2007, 585-600.

Palmieri 1978

A. Palmieri, Scavi ad Arslantepe (Malatya).

Quaderni de «La Ricerca Scientifica» 100, (Rome 1978) 311-352.

Palumbi 2010

G. Palumbi, Pastoral models and centralised animal husbandry. The case of Arslantepe. In: M. Frangipane (ed.), Economic Centralisation in Formative States. The archaeological reconstruction of the economic system in 4th 4^{\text {th }} millennium Arslantepe. Stud. Preist. Orient. 3 (Rome 2010) 149-163.

Polanyi 1944

K. Polanyi, The great transformation. The political and economic origins of our time (New York 1944).

Pollock 1999

S. Pollock, Ancient Mesopotamia (Cambridge 1999).

Pollock 2012

S. Pollock, Politics of food in early Mesopotamian centralized societies. Origini 34, 2012, 153-168.

Pollock 2012a

S. Pollock (ed.), Between feasts and daily meals. Toward an archaeology of commensal spaces. eTopoi. Journal Ancient Stud., special vol. 2, 2012.

Price/Feinman 2012

D. T. Price/G. M. Feinman, Pathways to power. New perspectives on the emergence of social inequality (New York 2012).

Rothman 2001

M. S. Rothman (ed.), Uruk Mesopotamia and its neighbors. Cross-cultural interactions in the era of state formation (Santa Fe 2001).

Rothman 2002

M. S. Rothman, Tepe Gawra. The Evolution of a small, prehistoric center in northern Iraq. Univ. Pennsylvania Mus. Monog. 112 (Philadelphia 2002).

Safar et al. 1981

F. Safar/M. A. Mustafa/S. Lloyd, Eridu (Baghdad 1981).

Schmandt-Besserat 2007

D. Schmandt-Besserat, When writing met art (Austin 2007).

Stein 1994

G. Stein, Economy, ritual, and power in 'Ubaid Mesopotamia. In: G. Stein/M. S. Rothman (eds.), Chiefdoms and early states in the Near East (Madison Wisconsin 1994) 35-46.

Stein 2005

G. Stein, The political economy of Mesopotamian colonial encounters. In: G. Stein (ed.), The archaeology of colonial encounters. School Am. Research Advanced Seminar Ser. (Santa Fe 2005) 143-171.

Tobler 1950

A. J. Tobler, Excavations at Tepe Gawra (Philadelphia 1990).

Ut et al. 2011

J. A. Ut/P. Karsgaard/J. Oates, The spatial dimensions of early Mesopotamian urbanism. The Tell Brak suburban survey, 2003-2006. Iraq 73, 2011, 1-19.

Wilkinson et al. 2014

T. J. Wilkinson/G. Philip/J. Bradbury/R. Dunford/D. Donoghue/N. Galatsatos/D. Lawrence/ A. Ricci/S. L. Smith, Contextualizing early urbanization. Settlement cores, early states and agro-pastoral strategies in the Fertile Crescent during the fourth and third millen nia BC. Journal of World Prehist. 27,1, 2014, 43-109.

Yoffee 2015

N. Yoffee (ed.), Early cities in comparative perspective, 4000 BCE-1200 BCE. The Cambridge world history 3 (Cambridge 2015).

Source of figures

1 Archive Missione Archeologica Italiana nell’Anatolia OrientaleMAIAO

2 a Tobler 1950, Pl. XV; b Huot 1996, 149 Fig. 1; c after Jasim 1989, Fig. 2; d after Tobler 1950, Pl. XI; e Forest 1996, Fig. 84

3 Archive Missione Archeologica Italiana nell’Anatolia OrientaleMAIAO

4 a Boehmer 1999, Taf. 35; b courtesy of Archive Missione Archeologica Italiana nell’Anatolia Orientale - MAIAO

5 a-d Archive Missione Archeologica Italiana nell’Anatolia Orientale - MAIAO

6 Archive Missione Archeologica Italiana nell’Anatolia OrientaleMAIAO

7 a-f photos by R. Ceccacci; Archive Missione Archeologica Italiana nell’Anatolia Orientale - MAIAO

8 a-b Archive Missione Archeologica Italiana nell’Anatolia Orientale - MAIAO

9 a-b photos by R. Ceccacci; Archive Missione Archeologica Italiana nell’Anatolia OrientaleMAIAO

10 after plan of C. Alvaro, Sapienza University of Rome; Archive Missione Archeologica Italiana nell’Anatolia Orientale - MAIAO

11 a-c drawings by T. D’Este and M. Cabua; d drawing by T. D’Este; Archive Missione Archeologica Italiana nell’Anatolia OrientaleMAIAO

12 photo by R. Ceccacci; Archive Missione Archeologica Italiana nell’Anatolia Orientale - MAIAO

13 Archive Missione Archeologica Italiana nell’Anatolia OrientaleMAIAO

14 photos by R. Ceccacci; drawings by T. D’Este; Archive Missione Archeologica Italiana nell’Anatolia Orientale - MAIAO

Address

Prof. Dr. Marcella Frangipane Sapienza - University of Rome Department of Antiquities Piazzale Aldo Moro 5 00185 Rome Italy

marcella.frangipane@uniroma1.it

| Type of evidence | Questions |

|---|---|

| What percentage of the ancient population is represented by the available tombs? Is any section of the population missing from the available funerary evidence? Is it possible to state, whether gaps in the funerary record are the product of economic factors? | |

| Is the available funerary information representative of social groups? Which sectors of the society are reflected in the material evidence? | |

| Which material aspects (grave goods, funerary buildings, etc.) have been used in each society to express or to create differences within that society? Can these differences be interpreted in terms of power and/or economic exploitation or do they correspond to other types of social division? | |

| Are there hints pointing to the negative expression or camouflage of property? Is there evidence to suggest that economic and social differences were not enhanced, but rather levelled in funerary rituals? | |

| Which qualitative and quantitative criteria are used in each study to establish “wealth differences” between funerary contexts? | |

| Where wealth differences are apparent, what percentages (%) of the tombs belong to the very poor and to the very rich respectively? | |

| What material differences exist between age and sex groups? More specifically, can we identify rich child and female burials or do only males accumulate wealth? | |

| How do specific economic activities, property, taxation, etc. favour certain social classes/groups over others? | |

| What evidence is there for the storage and accumulation of wealth and surplus? Are products stored at the domestic level or centralised in certain buildings/ areas? In the latter case, can we distinguish between private storage (e. g. in a palace) and public facilities? | There is clear evidence of centralised storage in public complexes. It is probable there was private storage in the houses, but it is not so clearly evidenced. Redistribution practices in the 5th 5^{\text {th }}-early 4th 4^{\text {th }} millennium BC temples suggest that forms of centralised storage date at least from then. |

| Can we identify a communal or supra-domestic architecture? Are these structures to be understood as communal property, as group property or as the private property of individuals? | Yes, there was religious ceremonial architecture and a very early palace complex. These were the seats from where elite groups exercised their power. |

| What can be said about the economic organisation of the society in question? Who profited from possible centralisation? Which section of the economy do these centralised productions represent? Is there evidence of administration reflecting the appropriation of value by a restricted group of persons? | The political economy in early Mesopotamian societies was based on the control of staple production and the labour force. Redistribution was aimed at feeding labourers and symbolically giving benefits back to the population. But the ruling elites and possibly their delegates were the main beneficiaries. Administrative practices were of basic importance. |

| Hoards can also be seen as a form of accumulation or way of cancelling surplus. How do we interpret hoards in economic and social rather than ideological terms? | Since the accumulation of “wealth” mainly concerned staple products, there were no real hoards. Production of luxury goods was intended to be displayed to symbolically emphasise positions of status and power. |

| What is the role of violence in the establishment of class differences? | Social order was mainly established through ideology and administration. Violence started to have a role at the end of this period. |