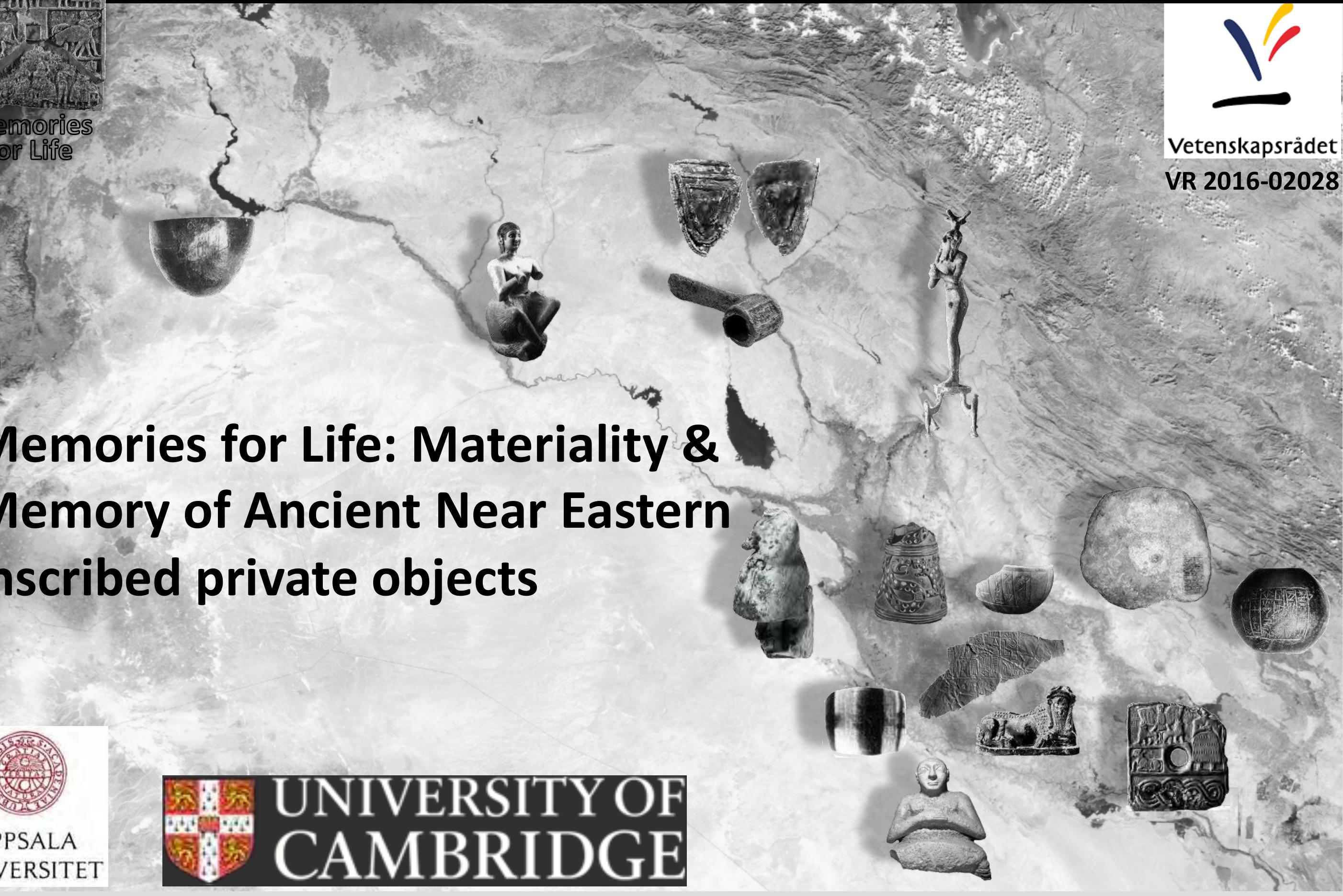

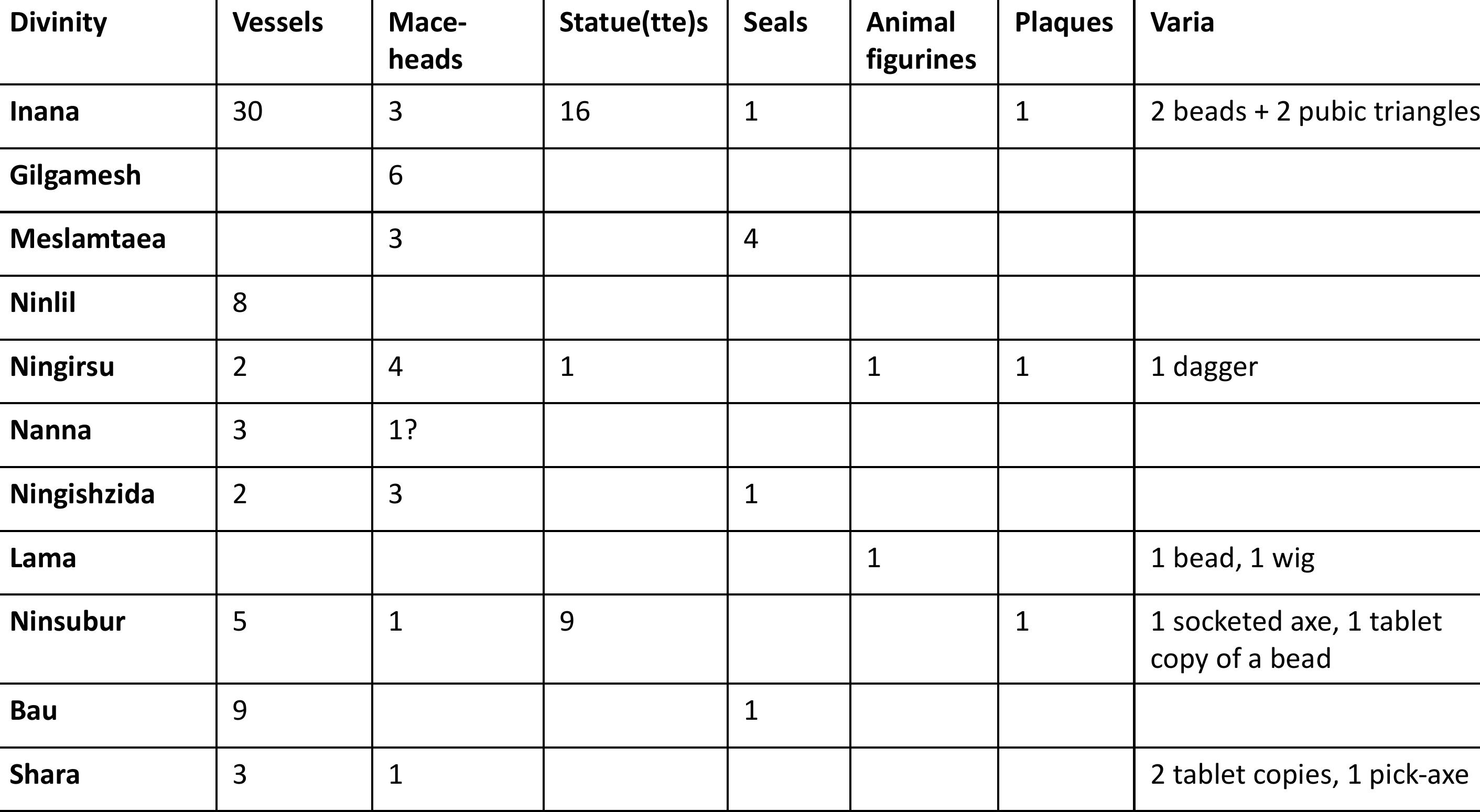

"Memories for Life: Materiality and Memory of Ancient Near Eastern inscribed private objects" (original) (raw)

Abstract

This is the presentation of the project "Memories for Life: Materiality and Memory of Ancient Near Eastern inscribed private objects", run by Jakob Andersson (Uppsala) and Christina Tsouparopoulou (Cambridge), and funded by the Swedish Research Council for the period 2017-2020.

Figures (20)

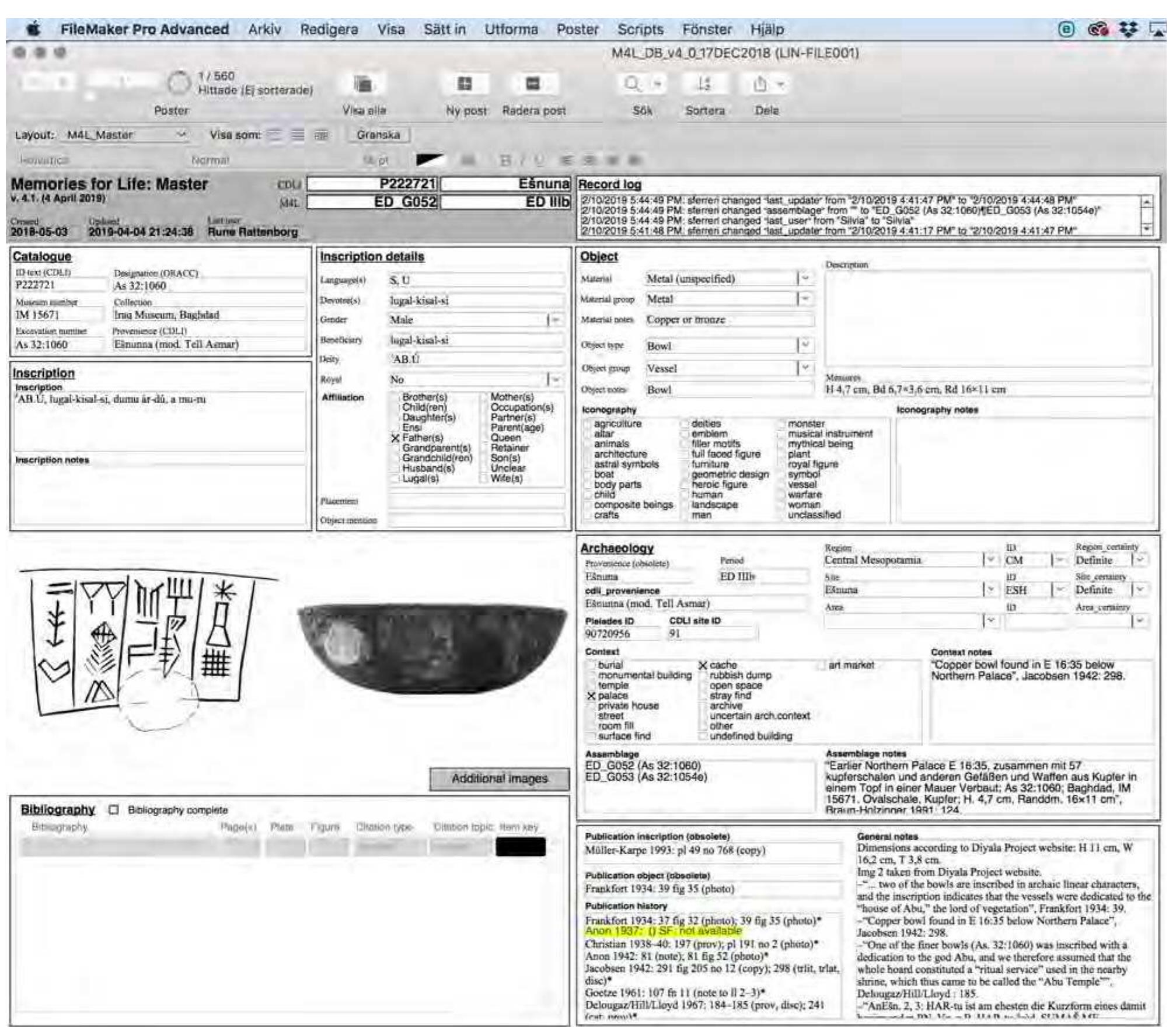

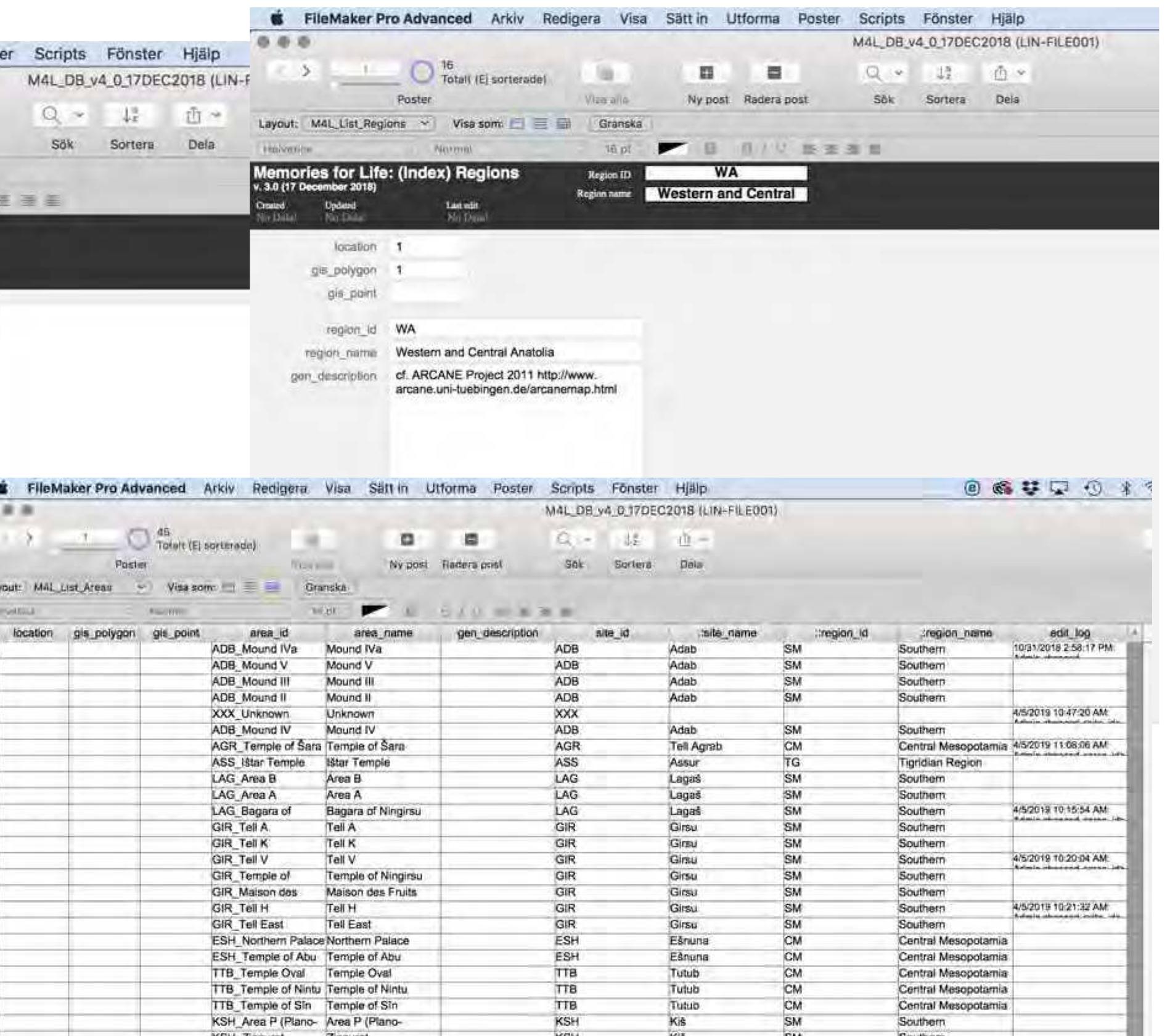

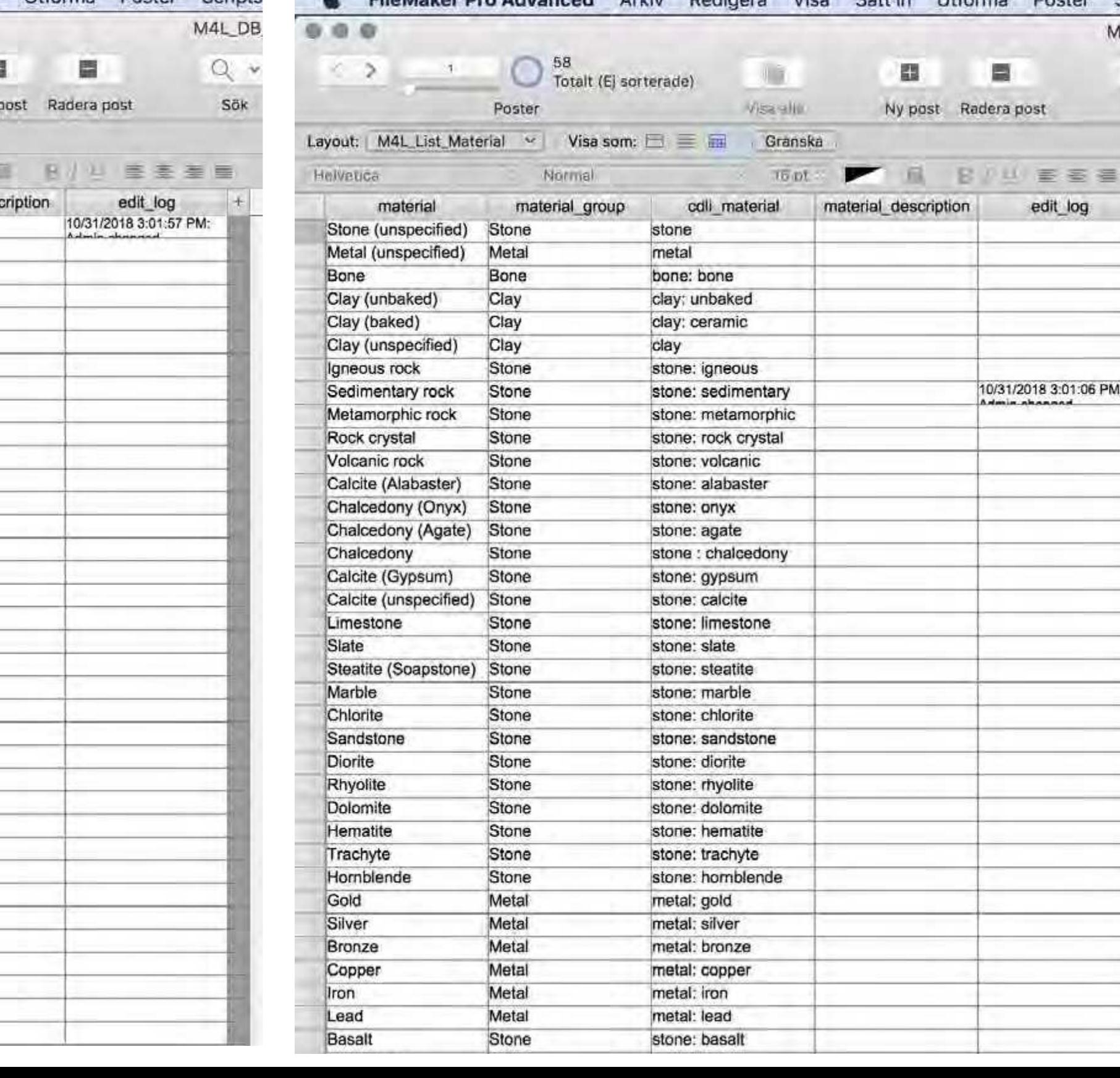

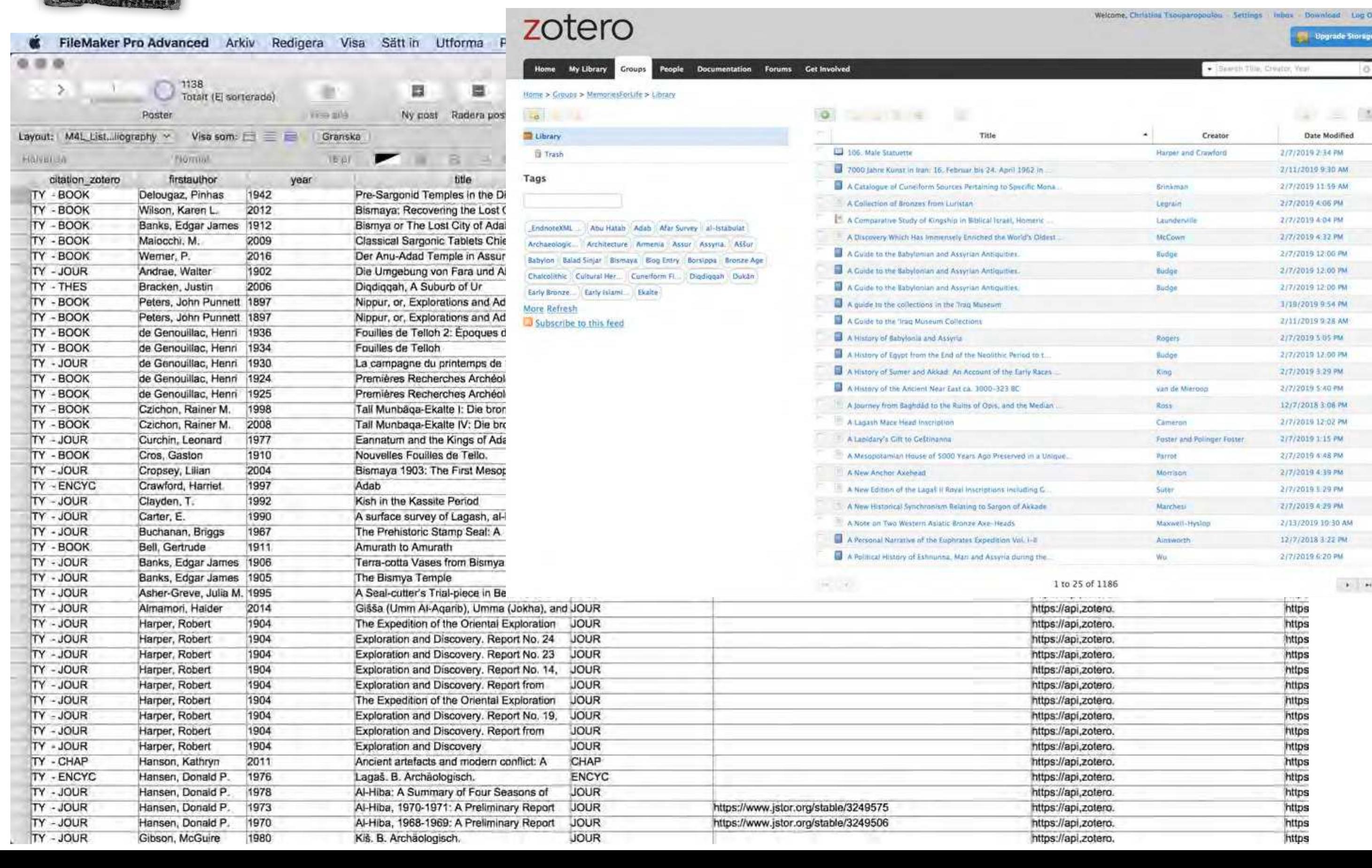

n the database : Filemaker Master file

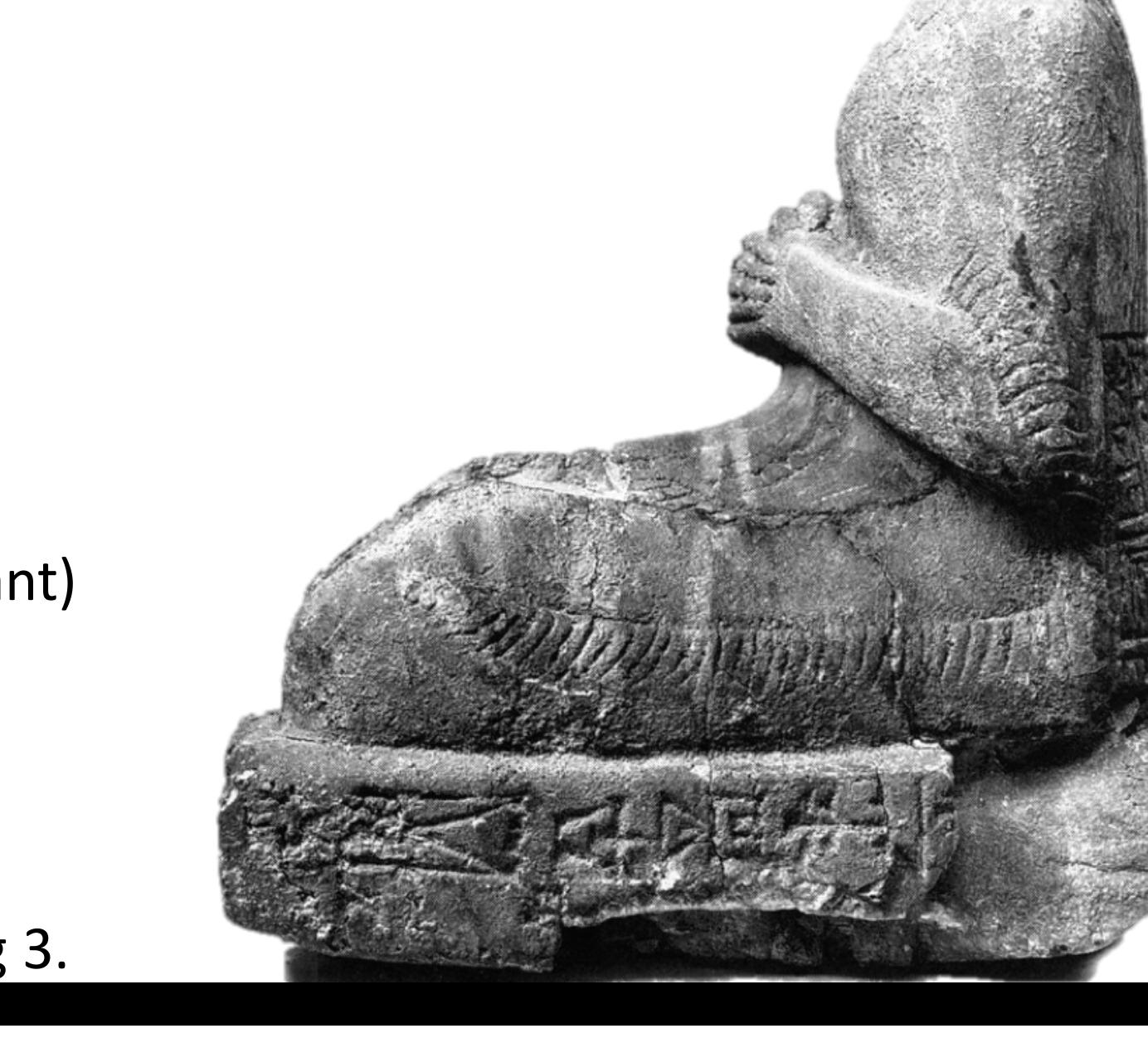

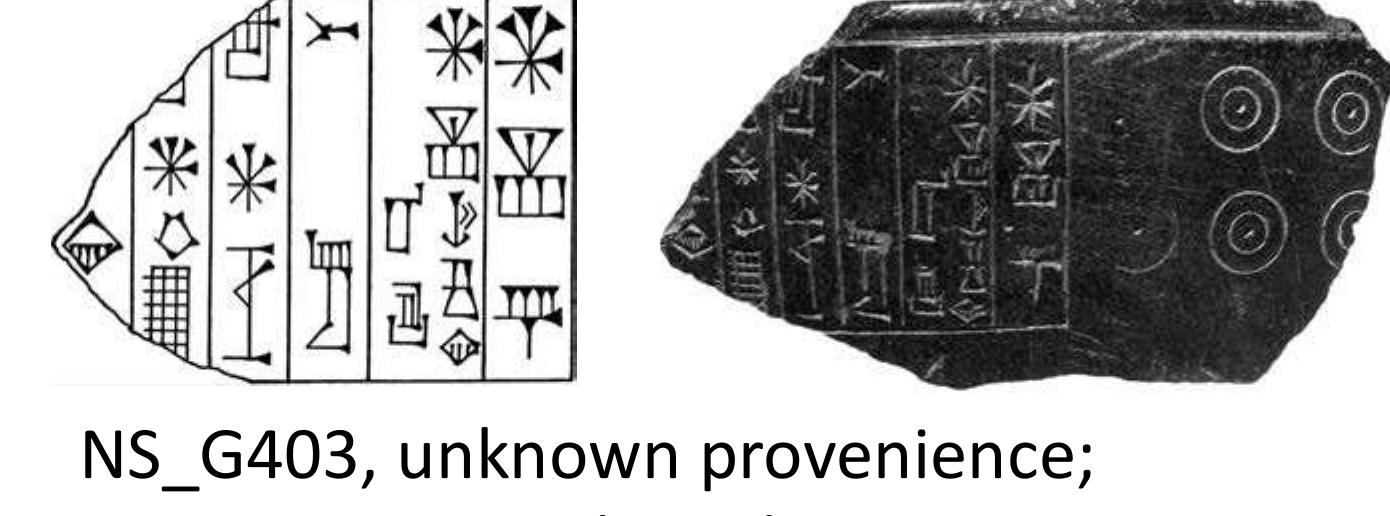

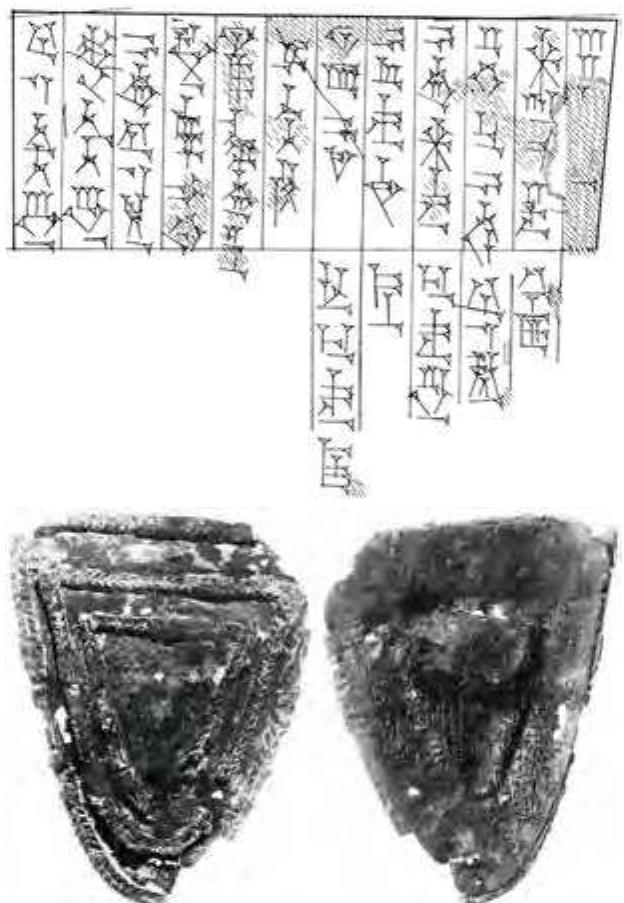

NS_G348, Ur, Gipar, Larsa level; Gadd and Legrain, UET 1 pl XII no 5.

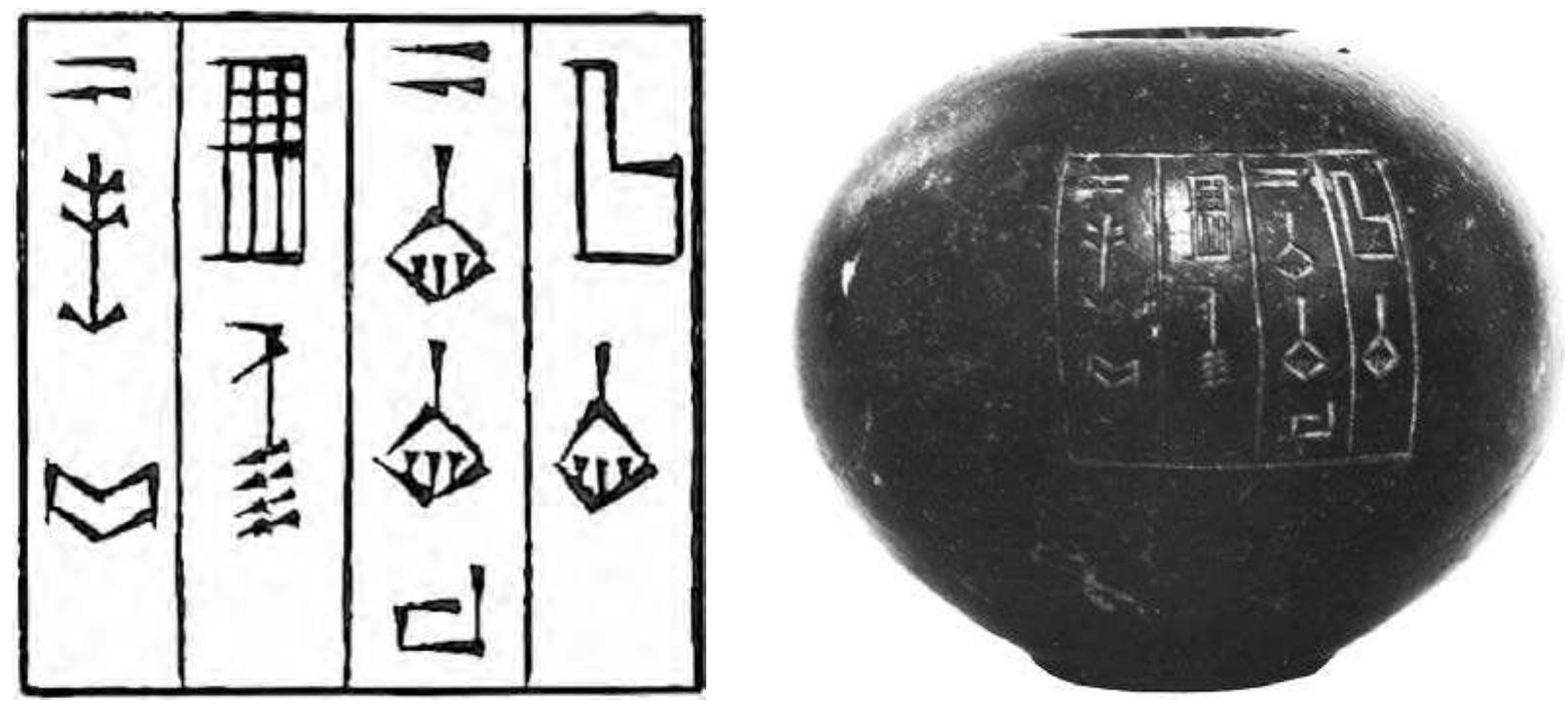

INO_IVIVV LS, UTIKRTIOWTT VIOVETHEMCe Limet, Textes sumériennes de Ia III? dynastie d’Ur (1976), pl 1 no 2; CDLI P135175

OA_Var14, Assur, Ishtar Temple, E cella; Jakob-Rost/Freydank, AoF 8 (1981), pl XXIII Jakob-Rost, Sumer 42 (1986), 98-99 Two metal pudenda, one in silver, one in copper, offered to Ishtar of Assur.

NS_MWx21, Assur, fc 6IIl; Wartke, Das Vorderasiatische Museum, Berlin (1992), 147 no 88

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

References (6)

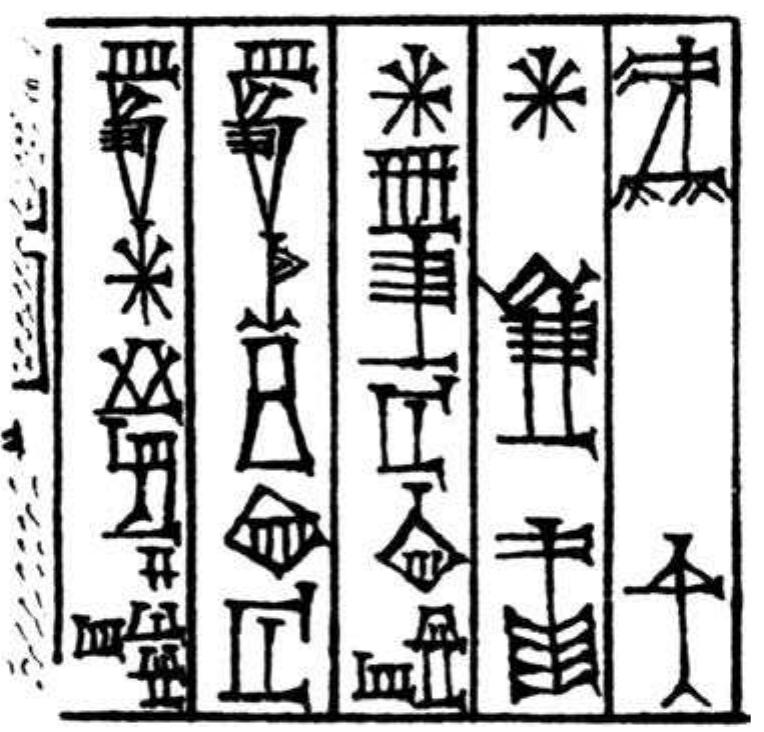

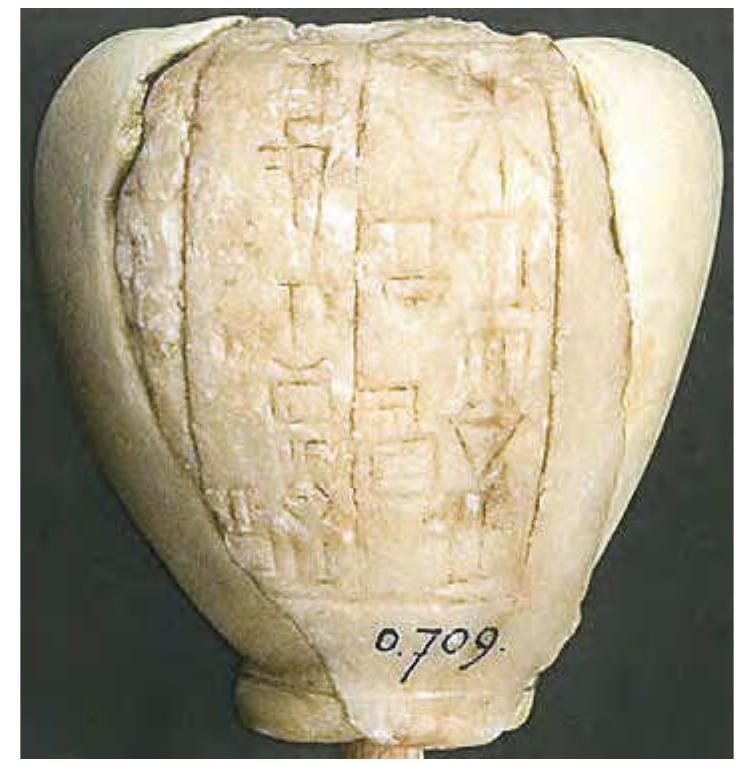

- sometimes clearly related to functions of the divine recipient. ED_Kx003, Unknown provenience; Crüsemann et al, Uruk -5000

- Jahre Megacity (2013), 53 fig 5.3

- Six mace-heads were dedicated to the deified Gilgamesh. ED_K016, Unknown provenience; Crüsemann et al, Uruk -5000 Jahre Megacity (2013), 53 fig 5.4

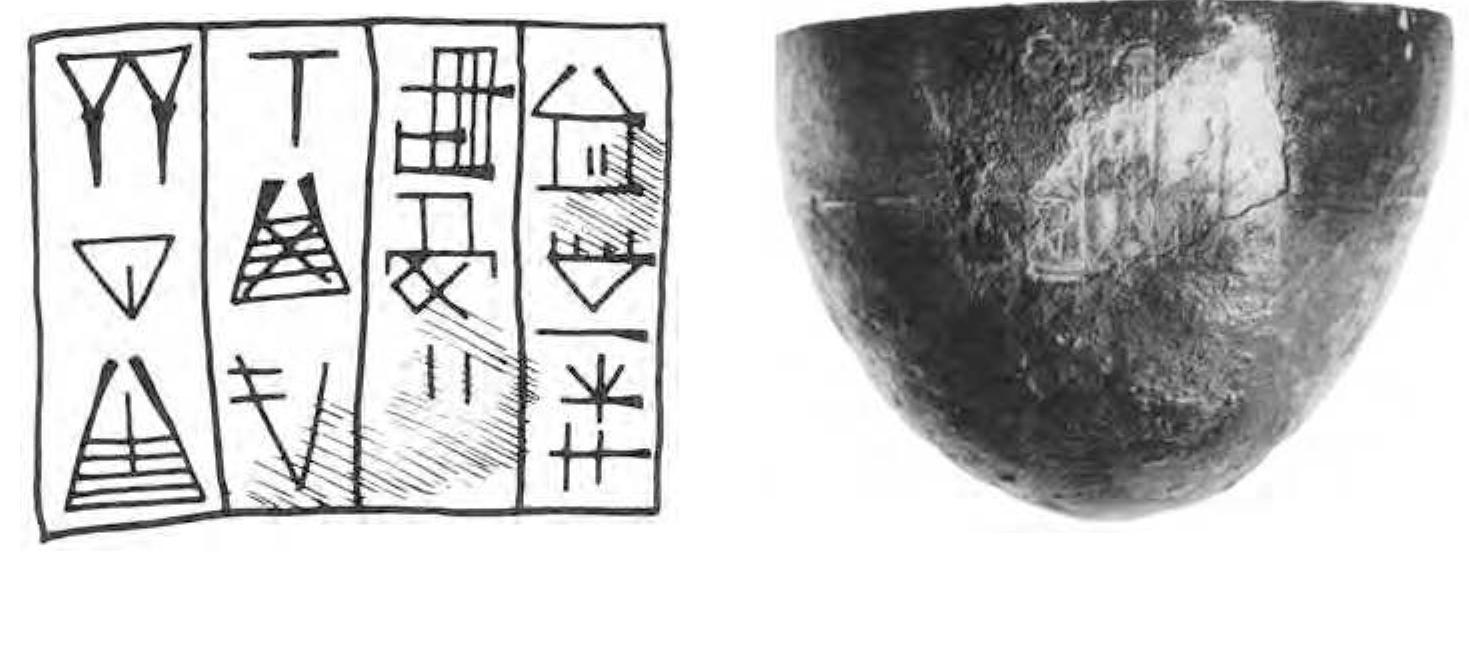

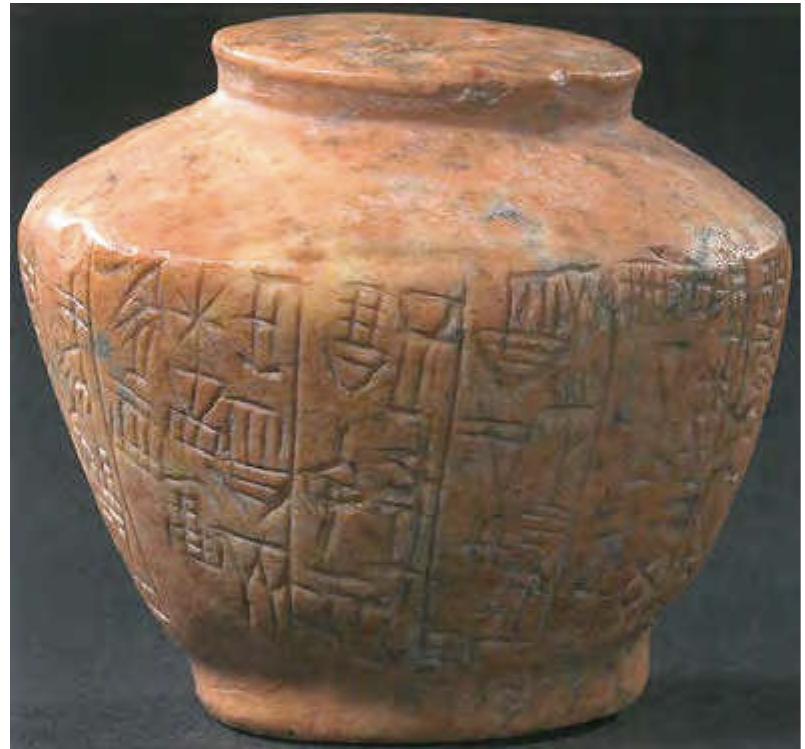

- Relationship between votee and object Objects sometimes clearly related to the office of the person commissioning the object. Metal weapons, offered by military service people, e.g. bronze adzes by a lieutenant in the Ur III army and by a captain in Assur during the same period. NS_MWx21, Assur, fc 6III;

- Wartke, Das Vorderasiatische Museum, Berlin (1992), 147 no 88

- NS_MW14, Unknown provenience CDLI P135175