Inclusive Christianity: A Framework from Biblical Hospitality Customs (original) (raw)

Abstract

This paper presents a framework drawn from biblical hospitality customs aiming to improve disability practices within the Church. Attention is drawn to Catholic Social Teaching and the prevalence of disability to inform the need for improving pastoral practice. A historical investigation into hospitality customs provides a context for biblical analysis and analogy. The disabled community is argued to be analogous to the hospitality practice given to ‘strangers’ in Ancient Near Eastern customs. Hence, both Old Testament and New Testament accounts of hospitality are to be investigated. Key biblical passages, such as Luke 4:14–30, Luke 14:16–21, Lev 19:33–34, and Isa 25:6– 10, are examined in light of the analogy between ‘disabled-stranger’ paradigm. The findings of the paper conclude that the application, mutatis mutandis, of ancient practices into the modern context is relevant. Its relevancy leads to a call for the Church to be a hospitable host to all who wish to eat at the table of God in the Eucharist. Ultimately, it is hoped that this paper would provide the disabled community with a first step toward better access and inclusion to Church life than they currently have.

FAQs

AI

What did the 2016 report reveal about disability within Australian Catholic communities?add

The report indicated that between 5.8 and 9.15 percent of Catholics reported disabilities in 2016, highlighting a low representation relative to their prevalence in the general population.

How does biblical hospitality inform modern church practices regarding inclusion?add

The study outlines that biblical hospitality emphasizes acceptance and inclusion, particularly for the disabled, using Old Testament and New Testament examples as frameworks for modern practice.

What challenges do disabled individuals face within Australian Church communities?add

In 2014-2015, 8.6% of disabled individuals faced reported discrimination, escalating to 20.5% among youths aged 15-24, indicating significant barriers to inclusion in church settings.

How does the concept of 'the stranger' relate to disabled individuals in biblical teachings?add

The paper illustrates that both disabled individuals and strangers serve as marginalized groups within communities; hospitality extended to them reflects biblical principles of inclusion and acceptance.

What role does social justice play in the teachings about hospitality in scripture?add

Scriptures such as Luke 4:16-21 emphasize social justice as a core element of acceptance, urging the church to continually invite and include marginalized individuals into their communities.

Figures (1)

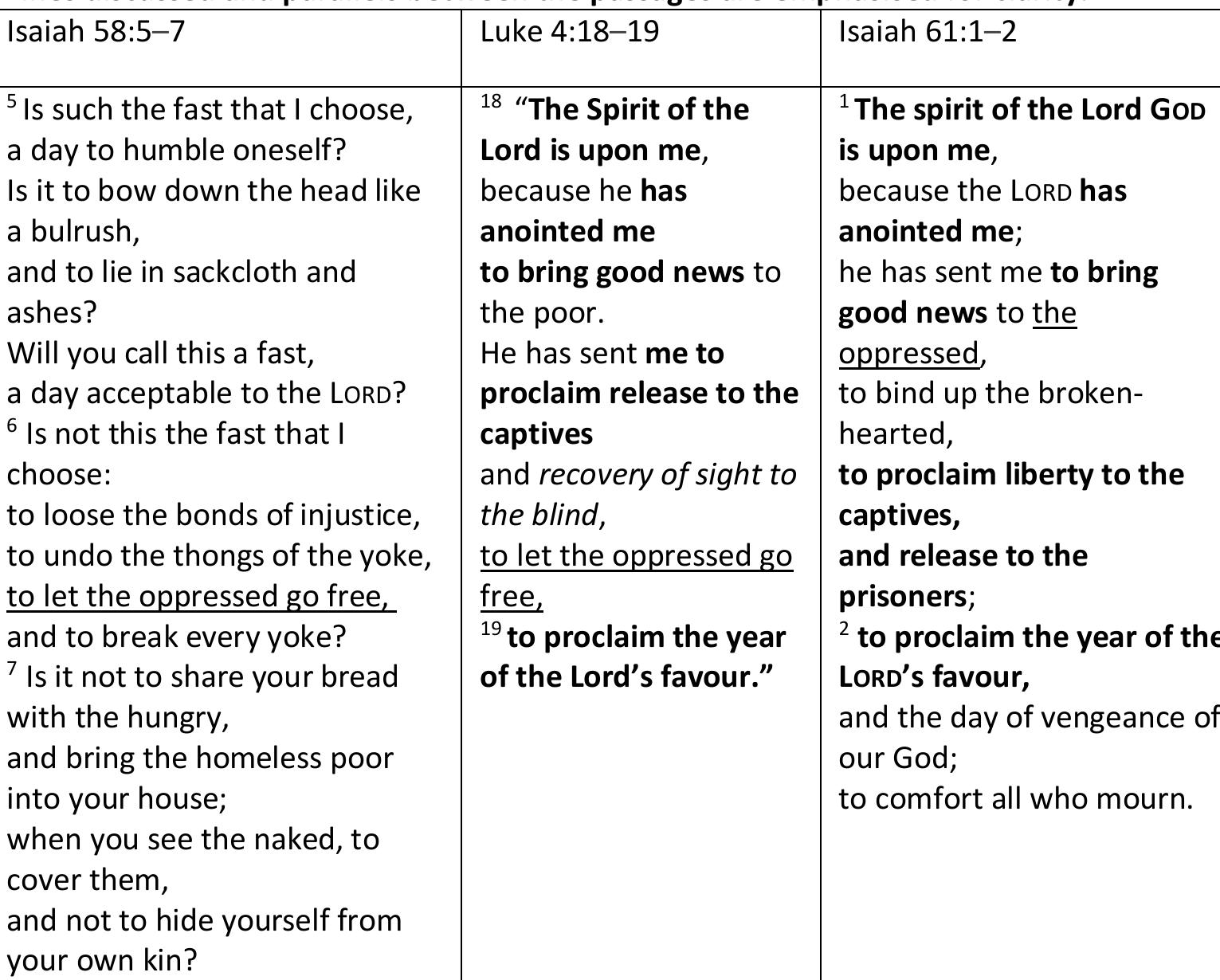

Since the majority of vv.18—19 derive from Isa 61:1—2, the context of Isaiah announcing his message to those returning from exile is significant. It is a message for those coming home to God.*° The fourth clause from Isa 61:1 (binding the broken-hearted) is removed, whereas ‘to let the oppressed go free’ (Isa 58:6) is added further on. By including this section of Isa 58:6, the wider context of the hospitality and the social justice imperative announced in Isa 58:5—7 is applied to the whole quotation.®’” The additional context implies that Jesus’ mission will fulfil the social justice and hospitality requirements expected of Israel in the OT. Moreover, in carefully choosing the starting and finishing lines of each passage, the quote expounds the acceptance (rather than vengeance) of the mission of Jesus, and thus, the Church.® In proclaiming the year of the Lord’s favour, divine acceptance is seen to be ongoing.®? Additionally, acceptance/non-acceptance henceforth becomes a cornerstone of Jesus’ ministry in Luke.°°

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

References (117)

- Louise Gosbell, 'The Parable of the Great Banquet' (Luke 14:15-24), CBM [Christian Blind Mission] and the Church: Churches as Places of Welcome and Belonging for People with Disability, St Mark's Review (2015), pp. 109-119, accessed 1 September 2019, https://search.informit.com.au/documentSummary;dn=423717896827199;res=IELHSS;

- Jackie Hiller-Broughton and Geoff Broughton, 'The Political Narrative of Disability Support Reform: Implications for the Church, Theology and Discipleship,' St Mark's Review (2015), pp. 96-108, accessed 4 August 2019, https://search.informit.com.au/documentSummary;dn=423699263855941;res=IELHSS. reported as disabled. Trudy Dantis, Stephen Reid, Leith Dudfield, Marilyn Chee, and Paul Bowell, 'Social Profile of the Catholic Community of Australia based on the 2016 Australian Census,' NCPR, 'National Catholic Census Project 1991-2016,' Australian Catholic Bishops Conference (ACBC), pp. 4 & 12, accessed 2 September 2019, https://ncpr.catholic.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Social-Profile-of-the-Catholic- Community-in-Australia-2016.pdf; see also Gosbell, 'The Parable of the Great Banquet,' pp. 116-117.

- Second Vatican Ecumenical Council in Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace, Compendium of the Social Doctrine of the Church, [United States Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB) Publishing: Washington, 2004], pp. 58-59; Ron Pagnucco and Mark Ensalaco, 'Human Rights, Catholic Social Teaching, and the Liberal Rights Tradition,' in A Vision of Justice, ed. Susan Crawford Sullivan and Ron Pagnucco (Minnesota: Liturgical Press, 2014), pp. 139-143;

- Zachary R. Calo, 'Catholic Social Thought and Human Rights,' American Journal of Economics and Sociology (2015), pp. 94-100, accessed 10 September 2019, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/ajes.12088.

- Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace. Compendium of the Social Doctrine, pp. 63-65.

- HarperCollins Publishers, 2019), pp. 73, 74 & 76; Charis Anna Hill, 'Ableism Killed My Christianity,' BeingCharis, Archives: June 2019, accessed 30 July 2019, https://beingcharis.com/2019/06/22/ableism-killed-my-christianity/.

- Gosbell, "The Parable of the Great Banquet," p. 117.

- Ibid., p. 117; Claire Swinarski, 'Honoring the Dignity of Our Sisters with Disabilities' The Catholic Feminist Podcast, Episode 52, accessed 1 October 2019, https://www.thecatholicfeministpodcast.com/shownotes/lindsey.

- Gosbell, 'The Parable of the Great Banquet,' p. 117; Hill, 'Ableism Killed My Christianity.'

- Hiller-Broughton and Broughton, 'The Political Narrative of Disability,' pp. 97-99 & 103.

- Hobbs in Lee Roy Martin, 'Old Testament Foundation for Christian Hospitality,' Verbum et Ecclesia (2014), p. 5, accessed 5 September 2019, https://verbumetecclesia.org.za/index.php/ve/article/view/752;

- Ruth B. Edwards, 'Entertaining Angels: Early Christian Hospitality in its Mediterranean Setting by Andrew E. Arterbury,' The Journal of Theological Studies (2007), pp. 678-681, accessed 13 September 2019, https://academic-oup-com.ezproxy2.acu.edu.au/jts/article/58/2/678/1671600/.

- Martin, 'Old Testament foundation for Christian Hospitality,' p. 5.

- Mary J. Marshall, 'Jesus: Glutton and Drunkard?,' Journal for the Study of the Historical Jesus (2005), p. 48, accessed 27 July 2019, https://doi.org/10.1177/1476869005053865;

- Brendan Byrne, The Hospitality of God: A Reading of Luke's Gospel, rev. ed. (St Pauls Publications: Strathfield, 2015);

- Michele Grottola, 'The Spiritual Essence of Hospitality Practice: Seeing the Proverbial Stranger as a Pretext to Reading Ourselves,' Marriage & Family Review (1998), pp. 6-7, accessed 5 October 2019, https://doi- org.ezproxy2.acu.edu.au/10.1300/J002v28n01_01.

- Benita Manning Long, Coming Home: A Historical Assessment of Private Domestic Space as the Primary Locus of Christian Hospitality, (Duke University, 2016), pp. 16, 17 & 34. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, accessed 17 September 2019, https://search.proquest.com/docview/1862009644/8E041C6DC58344E5PQ/1?accountid=81 94.

- Edwards, 'Entertaining Angels,' p. 697.

- Note: this still includes the original travellers to whom hospitality was already being shown. Marshall, 'Jesus: Glutton and Drunkard?,' p. 48. 42 Ibid., p. 50.

- Timothy Wade Shirley, Toward Diverse and Inclusive Communities of Faith: A Study of Hospitality and Congregational Identity and Receptivity, (Mercer University, 2011), pp. 30- 31.

- Christine D. Pohl, 'Hospitality: Ancient Resources and Contemporary Challenges,' in Ancient Faith for the Church's Future, eds. Mark Husbands and Jeffery P. Greenman (Illinois: IVP Academic, 2008), p. 148.

- Ibid., 148; Wendy Mayer, 'Welcoming the Stranger in the Mediterranean East: Syria and Constantinople,' Journal of the Australian Early Medieval Association (2009), p. 89, accessed 4 October 2019, https://go-gale- com.ezproxy2.acu.edu.au/ps/i.do?ty=as&v=2.1&u=acuni&it=DIourl&s=RELEVANCE&p=AONE

- Marshall, 'Jesus: Glutton and Drunkard?,' p. 56.

- Matt 25:40; Pohl, 'Hospitality,' pp. 147-150.

- Martin, 'Old Testament Foundation for Christian Hospitality,' pp. 1-9.

- 49 Kamperidis quoted in Grottola, 'The Spiritual Essence of Hospitality Practice,' pp. 5-6.

- Pohl, 'Hospitality,' p. 155.

- Annang Asumang, 'And the Angels Waited on Him (Mark 1:13): Hospitality and Discipleship in Mark's Gospel,' The Journal of the South African Theological Seminary (2009), p. 21, accessed 29 September 2019, https://journals.co.za/content/conspec/8/09/EJC28240?crawler=true. 52 Benefits and protections for the disabled community are the anti-discrimination statements of the Church as well as many church-run charitable organisations and services that aim to meet various needs of disabled recipients. Whilst these are not always done in a holistic manner (as discussed previously) they do offer varying levels of benefit to the recipient. Gosbell, 'The Parable of the Great Banquet,' p. 116; Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace, Compendium of the Social Doctrine, pp. 64-65.

- Martin, 'Old Testament Foundation for Christian Hospitality,' pp. 5-8.

- Paul Lang-Kul Cho and Janling Fu, 'Death and Feasting in the Isaiah Apocalypse (Isaiah 25:6-

- ' in Formation and Intertextuality in Isaiah 24-27, eds., James Todd Hibbard, and Hyun Chul Paul Kim (Society of Biblical Literature, 2013) 117. American Council of Learned Society (ACLS) Humanities E-Book, accessed 10 October 2019, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/heb.32028.

- Beth Steiner, 'Food of the Gods: Canaanite Myths of Divine Banquets and Gardens in Connection with Isaiah 25:6,' in Formation and Intertextuality in Isaiah 24-27, eds., James Todd Hibbard, and Hyun Chul Paul Kim (Society of Biblical Literature, 2013) 100. American Council of Learned Society (ACLS) Humanities E-Book, accessed 10 October 2019, https://hdl- handle-net.ezproxy2.acu.edu.au/2027/heb.32028.

- Cho and Fu, 'Death and Feasting in the Isaiah Apocalypse,' pp. 135-136;

- Andrew T. Abernethy, 'Feasts and Taboo Eating in Isaiah: Anthropology as a Stimulant for the Exegete's Imagination,' Catholic Biblical Quarterly (2018), p. 400, accessed 1 October 2019, https://muse.jhu.edu/article/718883/pdf.

- J. J. M. Roberts and Peter Machinist, 'The Little Isaiah Apocalypse,' in First Isaiah (Augsburg Fortress Publishers, 2015), p. 322. Project Muse, accessed 1 October 2019, https://muse.jhu.edu/book/45955.

- Roberts and Machinist, 'The Little Isaiah Apocalypse,' pp. 322-323.

- Steiner, 'Food of the Gods,' p. 115.

- Abernethy, 'Feasts and Taboo Eating in Isaiah,' pp. 396-399.

- The splendour, equal distribution and access to food supports this point. Cho and Fu, 'Death and Feasting in the Isaiah Apocalypse,' pp. 134-135.

- Martin, 'Old Testament Foundation for Christian Hospitality,' p. 8; Roberts and Machinist, 'The Little Isaiah Apocalypse,' p. 323.

- Martin, 'Old Testament foundation for Christian hospitality,' p. 8. 65 Ibid., p. 8. 66 Isa 25, pp. 6-9

- Diane C. Kessler, 'Receive One Another…: Honouring the Relationship between Hospitality and Christian Unity,' Journal of Ecumenical Studies (2012): 377-378, accessed 9 September 2019, https://web-b-ebscohost- com.ezproxy2.acu.edu.au/ehost/results?vid=2&sid=1da5c3ab-93b6-402b-ac03- b7912af07bb9%40sessionmgr101&bquery=(SO+(Journal+of+ecumenical+studies.))AND(DT+ 2012)AND(TI+%22%22receive+one+another+%22)&bdata=JmRiPWE5aCZ0eXBlPTEmc2Vhcm

- NoTW9kZT1BbmQmc2l0ZT1laG9zdC1saXZlJnNjb3BlPXNpdGU%3d#ResultIndex_1.

- Bosman, 'Loving the Neighbour and the Resident Alien,' pp. 572, 575 & 581.

- Ibid., pp. 575 & 581. with the idea of oppression. Significantly, these rules are extended in vv.33- 34 so as to include non-Israelites. 70

- However, exactly who is entitled to this widening of community protections is arguable. Jin-Myung Kim understands vv.33-34 to be referring to non- Israelites living in Israel, therefore excluding some groups of people 71 and differentiating this level of acceptance from what Jesus said. 72 On the contrary, others see v.34 providing full inclusion for any stranger or foreigner into the familial ethos of Israelite community. 73 However, given historical precedent and purposeful distinctions between foreigner and stranger within OT hospitality, Kim's thesis seems more likely. 74 Moreover, this difference of opinion is continued in subtle translational differences between the verses. The word ֵ רג (gēr) appears three times in vv.33-34. 75 Bosman provides the common translation as 'resident alien' or 'sojourner' whilst also using 'stranger' interchangeably. 76 Kessler, New Revised Standard Version (NRSV- 1989 -ed) and Geron Fournelle use 'alien,' King James Version [KJV, 1611 - ed] uses 'stranger,' and New International Version [NIV, 1973 -ed] uses 'foreigner.' 77 In view of the specific terminology described earlier, the wider context of the passage and historical precedent, the translation 'stranger' seems most accurate. 78 Significantly, the link between the stranger and ה ֶרָ ז אַ ('aezrāh, 'native-born') is heightened through the remembrance of the status of Israel's ancestors as strangers in Egypt. 79 Since God mercifully delivered and protected them, a powerful ethical ethos is remembered when addressing others of this status. Remembering ancestral strangers prompts the necessity for love, neighbourly hospitality and the rejection of oppression 70 Ibid., p. 579.

- Martin, 'Old Testament Foundation for Christian Hospitality,' pp. 2-3.

- Bosman, 'Loving the Neighbour and the Resident Alien,' pp. 580-582 & 589.

- Ibid., pp. 580-582.

- Ibid., p. 580; Kessler, 'Receive One Another…,' pp. 377-378;

- Geron G. Fournelle, The Book of Leviticus, eds., William G. Heidt, Katherine Sullivan, Carroll Stuhlmueller and Barnabas M Ahern. Old Testament Reading Guide (OTRG), (Minnesota: The Liturgical Press, 1967), pp. 8 & 77.

- Bosman, 'Loving the Neighbour and the Resident Alien,' p. 580; Kessler, 'Receive One Another…,' pp. 377-378; Fournelle The Book of Leviticus, p. 77.

- Bosman, 'Loving the Neighbour and the Resident Alien,' p. 580.

- Kessler, 'Receive One Another…,' pp. 377-378; Bosman, 'Loving the Neighbour and the Resident Alien,' p. 581.

- Ibid., pp. 587-588.

- Byrne, The hospitality of God, p. 63.

- Ibid., p. 55; Pablo T, Gadenz, 'Jesus' Mission as Messiah Luke 4:14-44,' in The Gospel of Luke (Baker Academic, 2018), p. 86. ProQuest E-book Central, accessed 9 October 2019, https://ebookcentral-proquest-com-ezproxy2-acu-edu- au.ezproxy1.acu.edu.au/lib/acu/detail.action?docID=5504705#.

- Byrne, The hospitality of God, p. 56.

- This is not to deny the importance of the healing miracles, but to recognise that negative views of disability contribute to pernicious readings. Not all disabled people desire healing, nor do they need to be healed to be whole and dignified members of God's family.

- Byrne, The Hospitality of God, p. 61.

- Isa 61:2; Luke 4:19; Gadenz, 'Jesus' Mission as Messiah,' p. 94.

- Gosbell, 'The Parable of the Great Banquet,' pp. 111-112 & 115.

- Ibid., pp. 112-115.

- Ibid., 114; Louise A. Gosbell, 'The Poor, the Crippled, the Blind, and the Lame': Physical and Sensory Disability in the Gospels of the New Testament, (Macquarie University, 2015), 183- 205. Macquarie University Research Online, accessed 29 September 2019, http://minerva.mq.edu.au:8080/vital/access/manager/Repository/mq:49601.

- Byrne, The Hospitality of God, p. 61.

- Gosbell, 'The Parable of the Great Banquet,' p. 113.

- Ibid., pp. 112-113.

- 101 Luke 14:13.

- Joachim Schaper, 'Hebrew Culture at the Interface between the Written and the Oral' in Literacy, Orality, and Literary Production in the Southern Levant: Contextualizing Sacred Writing in Ancient Israel and Judah, ed. Brian B Schmidt, (Society of Biblical Literature, 2015), pp. 333-338. ProQuest E-book Central, accessed 16 October 2019, https://ebookcentral- proquest-com-ezproxy2-acu-edu- au.ezproxy1.acu.edu.au/lib/acu/detail.action?docID=3425753; Lyle J. Story quoted in Gosbell, 'The Parable of the Great Banquet,' p. 114. 103 Luke 14, pp. 7-13.

- Hospitality should strive to continually better itself and model itself on the kingdom of God, especially concerning the eucharist;

- Hospitality should be generous and unreserved;

- Barriers that inhibit equal participation should be dismantled, including through adaptation of existing programs; 107

- The stranger should be accepted as they are, as a full and unified member of the church community;

- Areas of acceptance and rejection within the community should be consciously examined. Wider social rejection of disability should be opposed;

- Hospitality should have a socially just undercurrent;

- In remembrance of our inclusivity, hospitality must extend to those who are considered different from the group. It must be extended to all, with no exceptions;

- Hospitality should be proactive and an expected requirement of Christian life. It is not an 'already completed' task;

- The stranger-turned-guest should be held in a place of equal honour with the rest of the community; and 104 Gosbell, 'The Parable of the Great Banquet,' p. 115; Byrne, The Hospitality of God, pp. 139-140.

- Gosbell, 'The Parable of the Great Banquet,' p. 115.

- Note: segregation on the basis of disability is included as a barrier to participation. Bibliography: Abernethy, Andrew T. 'Feasts and Taboo Eating in Isaiah: Anthropology as a Stimulant for the Exegete's Imagination.' Catholic Biblical Quarterly (2018): 393-408. Accessed 1 October 2019, https://muse.jhu.edu/article/718883/pdf.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 'Summary: Key Findings.' Australian Bureau of Statistics. 4430.0.10.001-Disability, Ageing and Carers, Australia: First Results, 2015. Accessed 3 August 2019. https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/0/56C41FE7A67110C8CA257FA 3001D080B?Opendocument.

- Australian Government. 'Fact sheet about the Royal Commission.' Australian Government. Royal Commission into Violence, Abuse, Neglect and Exploitation of People with Disability. Accessed 25 September 2019. https://disability.royalcommission.gov.au/Pages/default.aspx.

- Australian Network on Disability. 'Disability Statistics.' Australian Network on Disability Resources. Accessed 5 August 2019. https://www.and.org.au/pages/disability-statistics.html.

- Bosman, Hendrik L. 'Loving the Neighbour and the Resident Alien in Leviticus 19 as Ethical Redefinition of Holiness.' Old Testament Essays (2018): 571-590. Accessed 14 October 2019. doi: 10.17159/2312- 3621/2018/v31n3a10.

- 108 Gosbell, 'The Parable of the Great Banquet,' p. 117.

- Burcaw, Shane and Hannah Aylward. 'Top 3 WORST Dates of Our Relationship.' Squirmy and Grubs video, 24:22. June 5, 2019. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gyrgof0-7Wg.

- Byrne, Brendan. The Hospitality of God: A Reading of Luke's Gospel. rev ed. St Pauls Publications: Strathfield, 2015.

- Calo, Zachary R. 'Catholic Social Thought and Human Rights,' American Journal of Economics and Sociology (2015): 93-112. Accessed 10 September 2019, https://doi.org/10.1111/ajes.12088.

- Carroll, Matthew. 'A Biblical Approach to Hospitality.' Review and Expositor (2011): 519-526. Accessed 10 September 2019. https://doi.org/10.1177/003463731110800406.

- Cho, Paul Lang-Kul and Janling Fu. 'Death and Feasting in the Isaiah Apocalypse (Isaiah 25:6-8).' In Formation and Intertextuality in Isaiah 24-27. Edited by James Todd Hibbard, and Hyun Chul Paul Kim. Society of Biblical Literature (2013): 117-142. American Council of Learned Societies (ACLS) Humanities E-Book. Accessed 10 October 2019. https://hdl-handle-net.ezproxy2.acu.edu.au/2027/heb.32028.

- Dantis, Trudy, Stephen Reid, Leith Dudfield, Marilyn Chee, and Paul Bowell. 'Social Profile of the Catholic Community of Australia: Based on the 2016 Australian Census.' Australian Catholic Bishops Conference (ACBC) National Centre for Pastoral Research (NCPR). 'National Catholic Census Project 1991-2016.' Accessed 2 September 2019. https://ncpr.catholic.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Social-Profile-of- the-Catholic-Community-in-Australia-2016.pdf.

- Findlay, Carly. Say Hello. Sydney: HarperCollins Publishers, 2019.

- Fournelle, Geron G. The Book of Leviticus. Edited by William G. Heidt, Katherine Sullivan, Carroll Stuhlmueller and Barnabas M Ahern. 30 vols. OTRG. Minnesota: The Liturgical Press, 1967.

- Gosbell, Louise. 'The Parable of the Great Banquet (Luke 14:15-24)': Christian Blinds Mission (CBM) and the Church: Churches as Places of Welcome and Belonging for People with Disability. St Mark's Review (2015): 109-122. Accessed 1 September 2019. https://search.informit.com.au/documentSummary;dn=423717896827199;r es=IELAPA.

- Gosbell, Louise. 'The Poor, the Crippled, the Blind, and the Lame': Physical and Sensory Disability in the Gospels of the New Testament. Macquarie University Research Online, 2015. Accessed 29 September 2019. http://minerva.mq.edu.au:8080/vital/access/manager/Repository/mq:4960

- Hill, Charis Anna. 'Ableism Killed My Christianity.' BeingCharis. Archives: June 2019. Accessed 30 July 30, 2019. https://beingcharis.com/2019/06/22/ableism-killed-my-christianity/.

- Hiller-Broughton, Jackie, and Geoff Broughton. 'The Political Narrative of Disability Support Reform: Implications for the Church, Theology and Discipleship.' St Mark's Review (2015): 96-108. Accessed 4 August 2019. https://search.informit.com.au/documentSummary;res=IELAPA;dn=423699 263855941.

- Holy Bible. King James Version [KJV, 1611 -ed]. Nashville: Thomas Nelson Publishers, 1982.

- Holy Bible. New International Version [NIV, 1973 -ed]. London: Hodder & Stoughton, 2006.

- Holy Bible. New Revised Standard Version [NRSV -ed]. Catholic Edition with Encyclopaedia. Washington: Bible Society Resources Ltd, 2008.

- Kessler, Diane C. 'Receive One Another…: Honouring the Relationship between Hospitality and Christian Unity,' Journal of Ecumenical Studies (2012): 376-384. Accessed 9 September 2019. https://web-b- ebscohost-com.ezproxy2.acu.edu.au/ehost/results?vid=2&sid=1da5c3ab- 93b6-402b-ac03- b7912af07bb9%40sessionmgr101&bquery=(SO+(Journal+of+ecumenical+stu dies.))AND(DT+2012)AND(TI+%22%22receive+one+another+%22)&bdata=J mRiPWE5aCZ0eXBlPTEmc2VhcmNoTW9kZT1BbmQmc2l0ZT1laG9zdC1saXZlJ nNjb3BlPXNpdGU%3d#ResultIndex_1.

- Long, Benita Manning Long. Coming Home: A Historical Assessment of Private Domestic Space as the Primary Locus of Christian Hospitality. Duke University, 2016. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing. Accessed 17 September 2019. https://search.proquest.com/docview/1862009644/8E041C6DC58344E5PQ/ 1?accountid=8194.

- López, Moisés. An Old Testament Theology of Disability. Fuller Theological Seminary, 2016. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing. Accessed 5 October 2019. https://search.proquest.com/docview/1809114934/EB212336D9AB4789PQ /1?accountid=8194.

- Marshall, Mary J. 'Jesus: Glutton and Drunkard?.' Journal for the Study of the Historical Jesus (2005): 47-60. Accessed 27 July 2019. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476869005053865.

- Martin, Lee Roy. 'Old Testament foundation for Christian Hospitality.' Verbum et Ecclesia (2014): 1-9. Accessed September 5, 2019. https://journals.co.za/content/verbum/35/1/EJC149614.

- Mitchell, David, and Sharon Snyder. 'Jesus Thrown Everything Off Balance: Disability and Redemption in Biblical Literature.' In This Abled Body: Rethinking Disabilities in Biblical Studies. Edited by Hector Avalos, Sarah Melcher, and Jeremy Schipper. Society of Biblical Literature, 2007. ProQuest E-book Central. Accessed 4 August, 2019. https://ebookcentral-proquest-com-ezproxy1-acu-edu- au.ezproxy2.acu.edu.au/lib/acu/detail.action?docID=3118184#.

- Pagnucco, Ron, and Mark Ensalaco. 'Human Rights, Catholic Social Teaching, and the Liberal Rights Tradition.' In A Vision of Justice: Engaging Catholic Social Teaching on the College Campus. Edited by Susan Crawford Sullivan and Ron Pagnucco (2014): 139-160. Minnesota: Liturgical Press.

- Pontifical Council For Justice and Peace. 'The Human Person and Human Rights.' In Compendium of the Social Doctrine of the Church (2004): 49-70. Washington: United States Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB) Publishing.

- Reynolds, Thomas E. 'Hospitality-Inspired Openness to the Other. In Vulnerable Communion: A Theology of Disability and Hospitality. Brazos Press, 2008. ProQuest E-book Central. Accessed 5 August 2019. https://ebookcentral-proquest- com.ezproxy2.acu.edu.au/lib/acu/detail.action?docID=583274#.

- Roberts, J. J. M. and Peter Machinist. 'The Little Isaiah Apocalypse.' In First Isaiah. Augsburg Fortress Publishers (2015): 306-341. Project Muse. Accessed 1 October 2019. https://muse.jhu.edu/book/45955.

- Schaper, Joachim. 'Hebrew Culture at the Interface between the Written and the Oral.' In Literacy, Orality, and Literary Production in the Southern Levant: Contextualizing Sacred Writing in Ancient Israel and Judah. Edited by Brian B Schmidt. Society of Biblical Literature, 2015. ProQuest E-book Central. Accessed 16 October 2019. https://ebookcentral-proquest-com-ezproxy2-acu-edu- au.ezproxy1.acu.edu.au/lib/acu/detail.action?docID=3425753.

- SCOPE. 'What is the Social Model of Disability?' Scope Video -Equality for Disabled People, 3:07. 6 August 2019. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0e24rfTZ2CQ.

- Shirely, Timothy Wade. Toward Diverse and Inclusive Communities of Faith: A Study of Hospitality and Congregational Identity and Receptivity. Mercer University, 2011. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing. Accessed 30 August 2019. https://search-proquest- com.ezproxy2.acu.edu.au/docview/864741739/50BE413B4BF9436CPQ/1?ac countid=8194.

- Steiner, Beth. 'Food of the Gods: Canaanite Myths of Divine Banquets and Gardens in Connection with Isaiah 25:6.' In Formation and Intertextuality in Isaiah 24-27. Edited by James Todd Hibbard, and Hyun Chul Paul Kim. Society of Biblical Literature (2013): 99-115. American Council of Learned Societies (ACLS) Humanities E-Book. Accessed 10 October 2019. https://hdl-handle- net.ezproxy2.acu.edu.au/2027/heb.32028.

- Swinarski, Claire. 'Honoring the Dignity of Our Sisters with Disabilities.' The Catholic Feminist Podcast, Episode 52. Accessed 1 October 2019. https://www.thecatholicfeministpodcast.com/shownotes/lindsey.

- United Nations. 'Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD).' Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Accessed 2 August 2019. https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/convention-on-the- rights-of-persons-with-disabilities.html.

- Walton, John H., Victor H. Matthews, and Mark W. Chavalas. The [Inter- Varsity Press -ed] IVP Bible Background Commentary: Old Testament. InterVarsity Press, 2000. Proquest E-book Central. Accessed 9 October 2019. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/acu/detail.action?docID=2029824.