The languages and linguistics of the New Guinea area: A comprehensive guide ed. by Bill Palmer (original) (raw)

1 Language families of the New Guinea Area

Bill Palmer

1.1. Introduction 1{ }^{1}

The New Guinea Area is arguably the region with the highest level of language diversity on earth, in terms of both total number of languages, and number of apparently unrelated language families. On the basis of present knowledge, it is home to more than 1,300 languages, almost one fifth of the world’s total number, belonging to upward of 40 distinct language families with no generally accepted wider phylogenetic links, as well as several dozen isolates 2{ }^{2}. It is also the world’s least documented linguistic region. Of Hammarström’s (2010) list of the 27 least documented families (including isolates) in the world, 20 are located in this area. In some cases, an entire family is known only from a few short wordlists of its members. The region is also the locus of considerable language endangerment. Many of its languages are spoken by a few hundred or very few thousand people, and extensive pressure from larger languages is common, including from larger indigenous languages supplanting smaller languages, and from lingua francas such as Tok Pisin in the east and Papuan Malay in the west. For the exceptionally complex Sepik-Ramu basin, for example, Foley (this volume chapter 3) states that “virtually all languages within the Sepik-Ramu basin are endangered, some critically so” (Foley’s emphasis). The sheer number of languages that are largely unknown to research, together with the rapid pace of language loss, means the complete phylogenetic and typological picture of the area may never be fully known. This volume sets out to give an overview of the languages, families and typology of this area on the basis of current knowledge.

1.2. The New Guinea Area

The island of New Guinea, the second largest in the world after Greenland, consists broadly of two ecological zones: highlands and lowlands. The highlands are

- 1 I am grateful to Harald Hammarström, Andrew Pawley, Nick Evans and Sebastian Fedden for comments on this chapter. All errors remain my own. I am grateful to Kay Dancey of ANU Cartographic for preparing most of the maps in this volume.

2 The New Guinea Area as defined in this chapter contains 862 identified languages of the various Papuan families, as well as upward of 450 Austronesian languages from southern and central Maluku, the Timor area, Aru, coastal mainland New Guinea, the islands of West Papua and Papua New Guinea, and the Solomon Islands. ↩︎

dominated by rugged mountains and fertile temperate valleys that support dense traditional farming populations. The more sparsely populated lowlands have a tropical climate, with large areas of swamp and some regions of savannah or hill country. Outside the mainland, the New Guinea Area includes a third ecological zone: the islands. Mainland New Guinea lies at the centre of a myriad of lesser islands. A few are small islands off the north or south coasts. Most, however, extend east through the Bismarck Archipelago and Solomon Islands out into the Pacific, and west into the Indonesian archipelago. How far into these eastern and western chains of islands can the New Guinea Area be construed as extending?

The Pacific islands to the east of New Guinea are often viewed as consisting of Near Oceania and Remote Oceania, following a distinction proposed by Pawley & Green (1973). Near Oceania refers to the network of intervisible islands including and extending from mainland New Guinea through the Bismarck Archipelago as far as the eastern limits of the main Solomon Islands chain. At the extreme of the last ice age, the Last Glacial Maximum around 21,000 years ago, sea levels were around 120-130 meters lower than at present. Even at that time, many of the island groups in Near Oceania remained separated by water. Indeed, while the region between the present south coast of New Guinea and northern Australia was a continuous continental landmass, the north coast of New Guinea and the coastlines of New Britain and New Ireland were largely identical to those existing today. However, at that time and continuing to the present day with its higher sea levels, aside from a number of tiny outlier islands and atolls, it was possible to see from one island to the next from mainland New Guinea as far east as the island of Makira at the eastern extremity of the Solomon Islands chain, or at the very least, to see the island ahead of you on the ocean while still within sight of the island you had left behind. Beyond the limits of Near Oceania lies Remote Oceania islands and island groups separated by expanses of open ocean requiring advanced maritime technology and navigational skills to cross. This notion of intervisibility defines the distinction between Near and Remote Oceania. Near Oceania extends as far east as Makira. Beyond that is Remote Oceania. The range of much of the fauna of New Guinea extends to the edge of Near Oceania as far as the eastern Solomons, although faunal diversity drops significantly towards the periphery of the region (Flannery 1995: 44-46). The same is true of the dispersal of human populations through the region. The earliest currently claimed archaeological site in New Guinea dates from 48,000 years bp (before present) (Hope & Haberle 2005: 542; see Allen & O’Connell 2014: 91). Parts of the eastern highlands were settled by 46,000 years bp (Allen & O’Connell 2014: 96; Summerhayes et al. 2010), and human settlement of the region had extended into the Bismarcks by 43,000 bp (Allen & O’Connell 2014: 91-92), and Greater Bougainville, a large island exposed by lower sea levels encompassing most of the Solomons chain, by 29,000 bp (Specht 2005, Spriggs 1997). The earliest confirmed archaeological date for the easternmost extent of Near Oceania, the relatively underinvestigated eastern

Solomons, is 6,000 bp for Guadalcanal (Duggan et al. 2014: 722), still well before the arrival of maritime Austronesian speaking peoples around 3,500 years ago. However, as Greater Bougainville in the late Pleistocene extended from today’s Buka almost to Guadalcanal, it seems likely that first settlement of Guadalcanal would have been much earlier. Beyond the limits of Near Oceania the time depth for human settlement is considerably shallower, beginning around 3,200bp3,200 \mathrm{bp}, and is associated with Austronesian dispersal into Remote Oceania into regions never previously inhabited by humans (Green 1991; Kayser 2014: R197; Spriggs 2011: 523). The open ocean beyond Near Oceania defines a natural geographic boundary that also represents a linguistic boundary, as well as a biogeographic boundary, including for pre-Austronesian human settlement of the Pacific.

To the west of mainland New Guinea a different natural boundary exists. At the Last Glacial Maximum many of the islands of the Indonesian archipelago were joined within two large landmasses exposed by the low sea levels. To the west, the Malay Peninsula, Sumatra, Java, Bali and Borneo were joined to mainland Southeast Asia in a landmass known as Sunda. In the east, New Guinea and a number of current islands, principally the Aru Islands, formed a single landmass with Australia and Tasmania, known as Sahul. Even at the lowest extent of sea levels, Sunda and Sahul were separated by deep ocean trenches. This boundary is reflected in very distinct suites of flora and fauna. Western Indonesia is home to Asian fauna types such as tigers, rhinoceros, monkeys and apes. New Guinea shares with Australia marsupials such as possums, kangaroos, echidna and bandicoots, as well as ratite birds such as the cassowary and other Australian bird species. The region between Sunda and Sahul, known as Wallacea, always contained separate islands, the largest being Sulawesi, which are home to a mix of Asian and Australia fauna types (Flannery 1995: 41-44). The Weber line running through Wallacea represents the westernmost extent of the region in which Australian-type fauna predominates. In terms of human populations, eastern Indonesia, broadly east of the Weber line but including East Nusa Tenggara containing the Timor area including the state of Timor Leste, displays a mix of genetic signals revealing unique population mixing of westward immigrants from Melanesia with eastward immigrants from East Asia, along with several genetic signals apparently indigenous to that region, some shared with Australia (Mona et al. 2009). In short, the region shows a unique mix of settlement from both New Guinea and Asia, overlaid on a pre-existing human population.

On the basis of this geographic, biogeographic and human settlement profile, the New Guinea Area can be defined as the region of the Sahul landmass north of continental Australia, along with its immediately adjacent islands, comprising the island of New Guinea and its offshore islands, extending in the west to the Wallacea fringe islands of Halmahera, Seram and Timor and their accompanying smaller islands including Alor and Pantar, and in the east to the Bismarck Archipelago and the Solomons group: a region bounded in the west by the Weber line and the Timor area and in the east by the extent of Near Oceania.

1.3. The Papuasphere

Numerous language families are represented within the New Guinea Area defined above. Two of these families, Austronesian and Pama-Nyungan 3{ }^{3}, are primarily located outside the New Guinea Area. The Pama-Nyungan family is represented in the New Guinea Area by a single language, Western Torres Strait, with its best known dialect Kala Lagaw Ya (Alpher et al. 2008; N. Evans et al. this volume). Otherwise, this family is found only on mainland Australia.

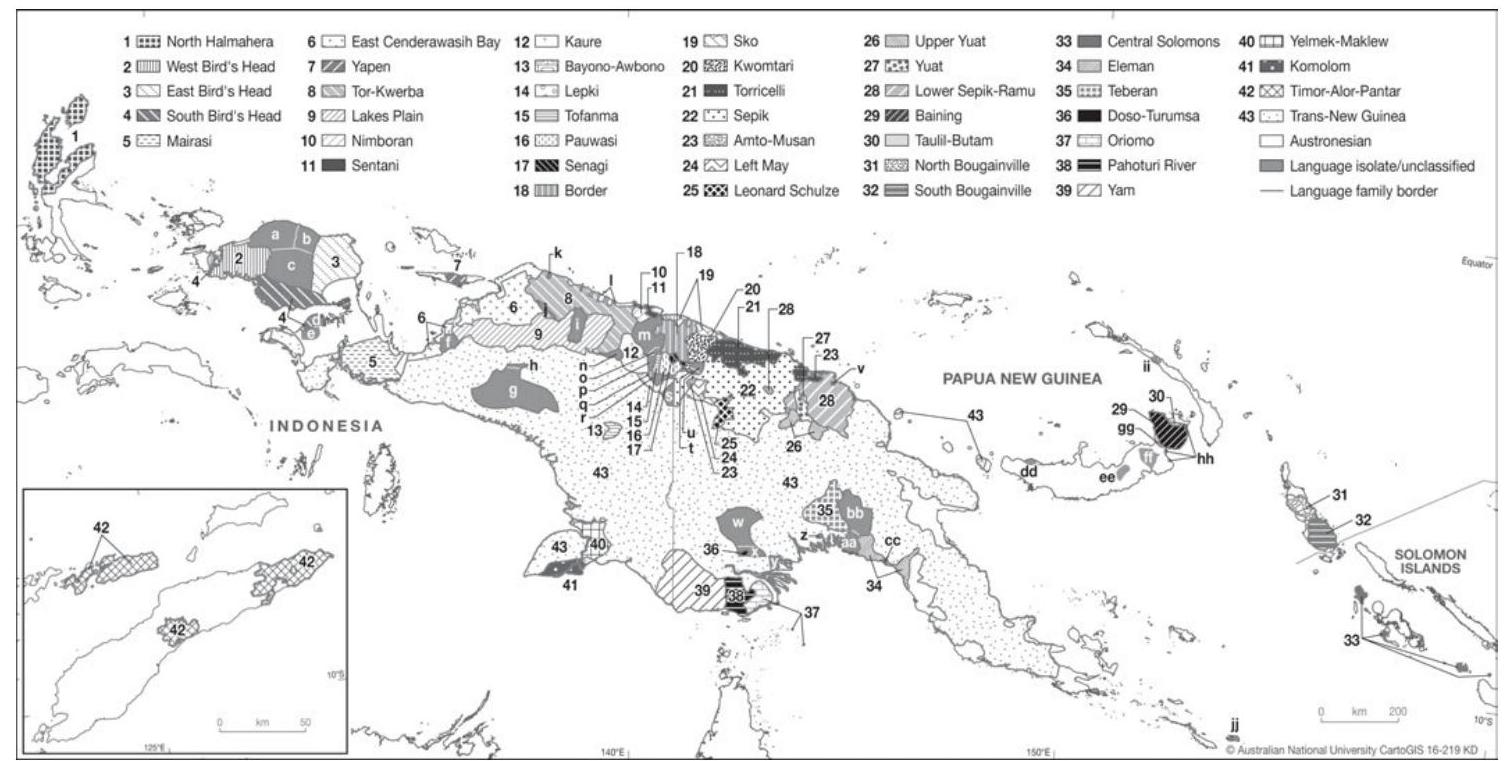

The Austronesian family, on the other hand, is represented in the New Guinea Area by numerous languages. While mainland New Guinea is overwhelmingly occupied by non-Austronesian languages, Austronesian languages are present in the Bird’s Neck 4{ }^{4}, sporadic pockets along the north coast, the region of the Markham Valley in the east, the southeasternmost tip, and eastern coastal areas of the Gulf of Papua (see Map 1.1). On the islands the situation is reversed. Austronesian languages dominate, with non-Austronesian languages confined to parts of the Timor area, northern Halmahera, east New Britain, Bougainville and the Solomon Islands. Nonetheless, despite the large number of Austronesian languages in the New Guinea Area, it remains a family the majority of whose members lie outside the region, in island and peninsula Southeast Asia and in the central and south Pacific. It is found across a very substantial portion of the globe, from Formosa in the north to New Zealand in the south, and from Madagascar in the west to Easter Island in the east. The Proto-Austronesian homeland is outside the New Guinea Area in Formosa, and of the family’s many major subgroups, few are found in the New Guinea Area.

These two families, Australian and Austronesian, differ from all other language families of the New Guinea Area in that they are primarily located outside the area. (As such, they are the focus of other volumes in the present series, on Australia, Southeast Asia and the Pacific.) The remaining 43 distinct language families identified in this volume are endemic to the New Guinea Area - all are found only within this complex region. It is these endemic families that are the focus of the present volume. 5{ }^{5}

- 3 The Pama-Nyungan family is viewed by many as belonging within a larger Australian language family, although this larger grouping is not universally accepted.

4 The island of New Guinea is often viewed as resembling a bird in shape, with the head facing west (see Map 1.1). The large peninsular in the northwest of the island is traditionally referred to as the Bird’s Head (dating back to the Dutch colonial period with the term Vogelkop). The narrower section of the island joining the Bird’s Head to the rest of the mainland is sometimes referred to as the Bird’s Neck. The southeastern extremity of the island in Papua New Guinea is sometimes referred to as the Bird’s Tail.

5 Papuan languages have been claimed to exist in two locations outside the New Guinea Area defined here. In the east, the Reefs-Santa Cruz languages are spoken on several small islands which, while politically part of the Solomon Islands, are midway between ↩︎

These endemic language families have traditionally been referred to as Papuan. However, aside from a few attempts at macrogrouping, such as Greenberg’s (1971) Indo-Pacific hypothesis, which was never widely accepted and has since been disproved (Pawley 2009), it is widely accepted that the non-Austronesian languages of the New Guinea Area cannot be shown to form a single family. Far from it. At the current state of knowledge the region contains 43 distinct Papuan families and 37 isolates identified in this volume (see Tables 1 and 2). Even if it were the case that all Papuan language families do ultimately reflect settlement of the region by a single linguistic population, and this is a highly unlikely scenario, the time depth involved would make it impossible to detect this ultimate phylogenetic unity using comparative linguistic methods. The island of New Guinea has been settled by humans for approaching 50,000 years. Over the intervening millennia, any linguistic signals reflecting shared ancestry would have been diluted to the point of being undetectable. In any case, it seems implausible to hypothesise that the region was only ever settled by a single linguistic population. If one human population was able to cross Wallacea and reach New Guinea bringing their language with them, it is implausible to imagine that this settlement event was never repeated. Combining that assumption with the current phylogenetic diversity of the region, it is reasonable to hypothesise that there was never a single ancestral Proto Papuan, and that at least some of the current language families reflect the arrival of separate linguistic populations into the region in deep time. The term Papuan therefore cannot be assumed to refer at any level, even in deep time, to a single phylogenetic group. For a time this view, or at least a recognition of the need to remain agnostic on phylogenetic links, prompted the use of “Non-Austronesian” (NAn) in place of “Papuan”, a term that gained some currency in the 1960s and 1970s (see

the Solomons chain and Vanuatu, and are the first group in Remote Oceania beyond the limits of Near Oceania. These were argued to be Austronesianized Papuan languages by Wurm (1978). However, in recent years they have been conclusively demonstrated to be members of a divergent high-order subgroup of the Austronesian Oceanic branch (Næss 2006; Næss and Boerger 2008; Ross and Næss 2007), so are not Papuan, vindicating Lincoln (1978). At the other end of the region, in Indonesia, an area around the volcano Tambora in central Sumbawa was home to a language that became extinct when almost its entire speaker population was wiped out in a cataclysmic eruption in 1815. This language was located within Wallacea, more than 500 kilometers to the west of the boundary of the New Guinea Area defined above. On the basis of an extremely small amount of data, a wordlist of fewer than 50 items collected at the beginning of the 19th Century by a colonial officer, Donohue (2007) makes a case that the language was Papuan, which he intends here to simply mean non-Austronesian. The data includes a handful of possible Austronesian etyma, potentially loans, but overall the lexicon does not look Austronesian. It is possible that more data would have shown it to be an aberrant Austronesian language, as with Reefs-Santa Cruz, or it may have been a pre-Austronesian relic. Tambora remains unclassified.

e. g. Capell 1969), but which, while phylogenetically sound, was unsatisfactory by defining a category of languages in negative terms. However, the term Papuan has no phylogenetic status.

In the early post-WWII decades of research into languages of New Guinea, the term “Papuan” developed something of a typological flavour (e. g. Capell 1969: 65−11665-116, especially the list of structural features on pp65-66), a sense that persists to some extent into the present. Papuan languages were regarded as a regional and to some extent typological grouping. It transpires that this was largely an artefact of how little was known at that time about languages of the region. There are a handful of linguistic characteristics that are widespread in the region: head-final structures, including OV ordering giving rise to SOV clause structure; a clear distinction between nouns and verbs; complex verb morphology; and head-marking for argument structure seen in verb agreement. However, while these are common, it transpires they are far from universal, and as more Papuan languages are described, and more is known about their structural characteristics, the more typological diversity is revealed, even in core aspects of putative Papuan typology such as clause structure and verb morphology. While it is possible to provide a meaningful typological overview of languages of the region (see Foley this volume chapter 8), as it is for any region, Papuan can no longer be considered in any way a typological grouping. Moreover, some of the structural similarities that do exist between some Papuan languages appear to have arisen through long periods of multilingualism, the region forming a large complex contact zone.

While the term ‘Papuan’ has no phylogenetic or typological status, it does refer to a group of families and isolates that share one crucial characteristic: all are endemic to the New Guinea Area. They are found wholly within the region, and have been in situ for a considerable period of time, significantly predating the arrival of Austronesian speakers around 3,500 bp. The term ‘Papuan’ can therefore be defined as referring to those languages and families that are endemic to the New Guinea Area and which represent a continuation of the region’s deep time linguistic history. The term ‘Papuasphere’ may be used to refer to the linguistic world which these families and isolates are located.

1.4. Language families of the Papuasphere

The Papuasphere, encompassing mainland New Guinea, the Bismarck Archipelago, Bougainville, the Solomon Islands, Halmahera, and the islands of Timor, Alor and Pantar, contains, by the current count, 862 languages comprising 43 distinct families (Table 1) and 37 isolates (Table 2). 6{ }^{6} A proper survey of the area must give

- 6 Any precise number of languages must be tentative and somewhat arbitrary, due to the difficulties distinguishing dialects from separate languages. In some cases, limited ↩︎

due weight to the phylogenetic and typological diversity of Papuan languages. It would be difficult to fully do justice to so many families and languages in a single volume, and the limited knowledge we have of many entire families or regions within the overall area compounds this difficulty. However, in recent years Papuan languages, families and regions have been the focus of an increasing amount of research. This volume provides the most thorough survey of the area possible at the time of writing.

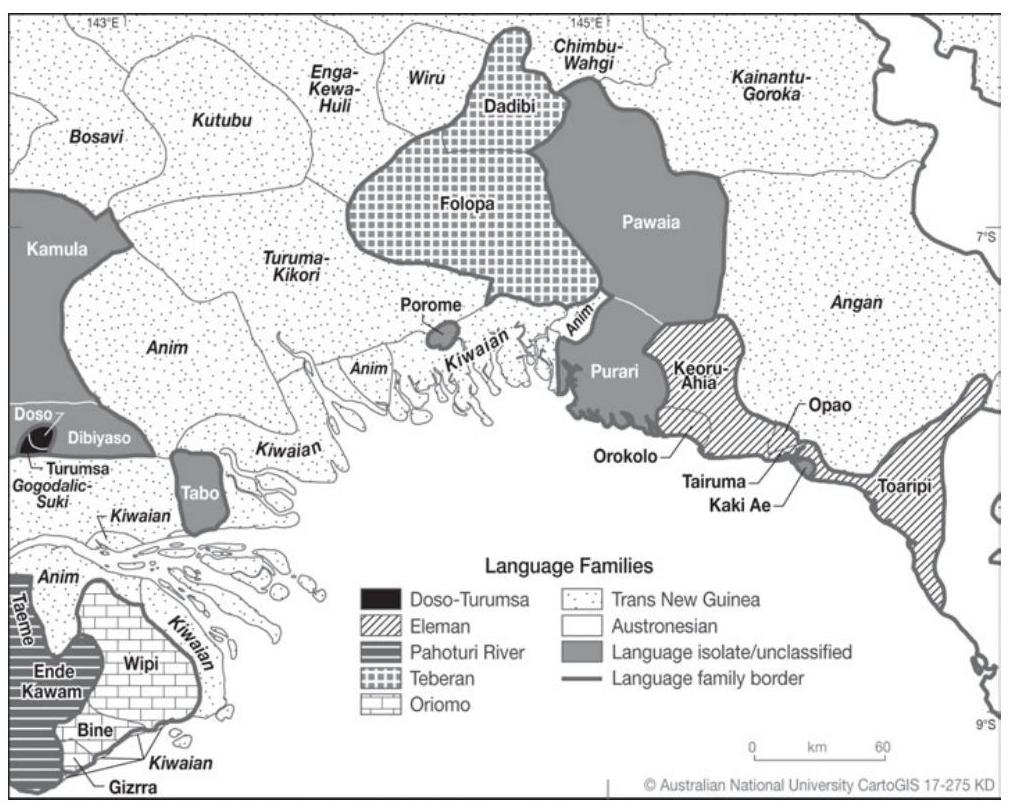

The overall New Guinea Area (Map 1.1) can be viewed as comprising a number of smaller geographic regions in which one or more groups of families are found. Each of these regions is surveyed in a chapter or section of a chapter in this volume. In the west, the islands of Timor, Alor and Pantar form a distinct linguistic region, as does the northern half of the island of Halmahera. Similarly, in the east, the Bismarck Archipelago (New Britain and New Ireland) forms a linguistic region, as does Bougainville, and the western and central Solomon Islands. On mainland New Guinea, the largest region comprises the Highlands, spreading west into the lowlands of south western New Guinea, and east to the coast of Madang in the north, the Gulf of Papua in the south and into the Bird’s Tail. This enormous region is dominated by languages belonging to the large Trans New Guinea (TNG) family, interspersed with occasional isolates and small families, typically of contested TNG membership. At the western end of the mainland the Bird’s Head forms a region that is home to several families and isolates. Along the mainland’s south coast, straddling the border between Indonesia and Papua New Guinea, lies a lowland region of considerable linguistic complexity, stretching from Kolopom Island in the west to the Fly River in the east. The Gulf of Papua is also home to a number of small families and isolates of disputed TNG membership (Map 1.2). Surpassing the southern region in language and family density, and significantly larger in size and numbers of families, the entire north coast and its interior from the base of the Bird’s Neck to east of the town of Bogia in Papua New Guinea forms a patchwork of numerous families, including the exceptionally complex Sepik-Ramu basin, almost certainly the phylogenetically most complex linguistic region in the world. Each of these regions is covered in a chapter of this volume, arranged anticlockwise from the centre of the area. Pawley and Hammarström’s chapter 2 covers the region dominated by Trans New Guinea, including the Gulf of Papua. The large north coast and Sepik-Ramu basin is surveyed in two chapters, broadly corresponding to the Papua New Guinea and Indonesian halves of the region. Foley’s chapter 3 covers the Papua New Guinea region from

data and data of varying quality and age means that the degree of mutual intelligibility between related communalects can only be estimated. In other cases, larger languages, such as Engan, represent highly complex dialect networks. The figure of 862 languages represents the best assessment on the basis of current knowledge, as presented in the regional survey chapters of this volume.

Table 1: Papuan language families, arranged by size 7{ }^{7}

| Family | no. langs | region | Family | no. langs | region |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trans New Guinea | 431 | Highlands/ southwestern/ eastern New Guinea | Pauwasi | 5 | North coast/hinterland |

| Torricelli | 50 | Sepik-Ramu basin | Yuat | 5 | Sepik-Ramu basin |

| Sepik | 45 | Sepik-Ramu basin | Central Solomons 8{ }^{8} | 4 | Solomon Islands |

| Lower Sepik-Ramu | 35 | Sepik-Ramu basin | North Bougainville | 4 | Bougainville |

| Yam | 27 | Southern New Guinea | Oriomo | 4 | Southern New Guinea |

| Timor-Alor-Pantar | 26 | Timor area | Sentani | 4 | North coast/hinterland |

| Tor-Kwerba | 23 | North coast/ hinterland | South Bougainville | 4 | Bougainville |

| Lakes Plain | 20 | North coast/ hinterland | Mairasi | 3 | North coast/hinterland |

| Border | 14 | North coast/ hinterland | Amto-Musan | 2 | Sepik-Ramu basin |

| Sko | 13 | North coast/ hinterland | Bayono-Awbono | 2 | Central West Papua |

| East Cenderawasih Bay | 10 | North coast/ hinterland | Butam-Taulil | 2 | Bismarck Archipelago |

| North Halmahera | 10 | Halmahera | Doso-Turumsa | 2 | Southern New Guinea |

| South Bird’s Head | 10 | Bird’s Head | Kaure | 2 | North coast/hinterland |

- 7 Numbers of languages in each family, particularly the larger families, should be taken as conservative and in many cases tentative. In some instances, isolates or small families may transpire to belong within existing larger phylogenetic groupings. In others, hitherto unrecognized languages may exist that belong to these families. In still other cases putative families may combine branches that turn out to be unrelated on closer investigation.

8 B. Evans (this volume) do not treat Central Solomons as a genetic grouping, citing a lack of cognate vocabulary greater than chance similarity, once loans are eliminated. However, Ross (2001:316-317) presents evidence leading him to conclude that many pronominal forms across the four languages are cognate (2001:311), evidence B. Evans et al (this volume) regard as promising. At this stage Central Solomons as a family must be regarded as tentative. ↩︎

| Family | no. langs | region L | Family | no. Langs | region L |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kwomtari | 6 | Sepik-Ramu basin | Lepki | 2 | North coast/hinterland |

| Leonard Schultze | 6 | Sepik-Ramu basin | Senagi | 2 | North coast/hinterland |

| Upper Yuat | 6 | Sepik-Ramu basin | Teberan | 2 | Gulf of Papua/ hinterland |

| West Bird’s Head | 6 | Bird’s Head | Tofanma | 2 | North coast/hinterland |

| Baining | 5 | Bismarck Archipelago | Komolom | 2 | Southern New Guinea |

| East Bird’s Head | 5 | Bird’s Head | Yapen | 2 | North coast/hinterland |

| Eleman | 5 | Southern New Guinea | Yelmek-Maklew | 2 | Southern New Guinea |

| Left May | 5 | Sepik-Ramu basin | Isolates total | 37 | all regions |

| Nimboran | 5 | North coast/ hinterland | TOTAL | 862 | |

| Pahoturi River | 5 | Southern New Guinea |

Table 2: Isolates and unclassified languages, grouped by region (with location on Map 1.1)

| Languages | no. langs | region |

|---|---|---|

| Abun (a), Mpur (b), Maibrat ©, Mor (e), Tanah Merah (d) | 5 | Bird’s Head/Bomberai Peninsular |

| Abinomn (i), Burmeso (j), Elseng (m), Kapauri (n), Kembra (q), Keuw (f), Kimki (s), Massep (k), Mawes (l), Molof (o), Usku (p), Yetfa ® | 12 | North coast/hinterland |

| Dem (h), Uhunduni (g) | 2 | Central West Papua |

| Busa (t), Taiap (v), Yadë (u) | 3 | Sepik-Ramu basin |

| Dibiyaso (x), Kaki Ae (cc), Kamula (w), Karami (extinct), Pawaia (bb), | 8 | Gulf of Papua/hinterland |

| Porome (z), Purari (aa), Tabo (y) | ||

| Anêm (dd), Ata (ee), Kol (ff), Kuot (ii), Makolkol (gg), Sulka (hh) | 6 | Bismarck Archipelago |

| Yélî Dnye (jj) | 1 | Rossel Island (Louisiade Archipelago) |

| Total | 37 |

Map. 1.1: Language families of the New Guinea Area. Families and isolates that are disputed possible members of TNG are treated separately in this map. (Isolates and unclassified languages are represented by letters and identified in Table 2).

Map. 1.2: Papuan families and isolates of the Gulf of Papua.

the Sepik-Ramu basin west to the international border, and into Indonesia with families that straddle the border. Foley’s chapter 4 continues the survey westward to east Cenderawasih Bay. The regions of the Bird’s Head, North Halmahera, and Timor, Alor and Pantar are discussed together in Holton and Klamer’s chapter on east Nusantara. The southern lowlands are surveyed by N. Evans and his collaborators in chapter 6. Finally, the three regions of island Melanesia - the Bismarck Archipelago, Bougainville and the Solomon Islands, are covered together by B. Evans et al. in chapter 7. The final two chapters of the volume give an overview of the area, from typological and language contact perspectives respectively.

1.5. Complexity of the research context

The situation presented in this volume, in terms of the numbers of languages and their phylogenetic affiliations, must be taken as to varying extents provisional, due to a lack of comparative research, and the extreme paucity of material on many

of the region’s languages. Hammarström (2010) lists what he identifies as the world’s least documented language families (including single member families, i. e. isolates). To qualify, a family has to not be extinct, and for all its members between them to have “less documentation than a rudimentary sketch grammar” (2010: 178) - i. e. no member of the family has any significant documentation. It is a testament to the unique language diversity and under-documented status of the New Guinea Area that of Hammarström’s 27 families, four are in South America, one each in Africa, India and Great Nicobar Island, and the remaining 20 are in New Guinea, primarily in West Papua. 9{ }^{9} In Hammarström and Nordhoff’s (2012) thorough survey of available materials on the languages of Melanesia, 13.8%13.8 \% of Papuan languages are documented in a full grammatical description ( 150 pages or more), and a further 17.9%17.9 \% are the subject of a grammar sketch, while 61.7%61.7 \% are represented by a wordlist or less (2012: 24). This makes the Papuasphere the world’s least documented region, both in terms of absolute numbers of languages, and in proportion of languages documented. By comparison, the next least documented region, Eurasia, is represented by proportionately almost three times as many full-length grammars ( 35.3%35.3 \% ), with significantly fewer languages ( 41.8%41.8 \% ) represented by a wordlist or less (Hammarström and Nordhoff 2012: 26). 10{ }^{10}

As a result of this under-documentation, no region of the world is less well understood in terms of the phylogenetic status of its languages. As Pawley and Hammarström (this volume) note in relation to several regions and to the periphery of Trans New Guinea, “the available information and/or existing comparative research has not been sufficient to allow firm conclusions on phylogenetic groupings”. In a few cases, sufficient work has been done on an isolate or small family to allow confidence that it is not demonstrably related to any other grouping in the area. In many more cases, small families and isolates must be treated as separate because the available data is insufficient to demonstrate any wider phylogenetic relationships, or because no significant comparative work has been done on them, or often both. In other words they are unclassified, rather than confirmed isolates or small families.

- 9 The island of New Guinea is divided between the state of Papua New Guinea in the east, and in the west the Indonesian provinces of Provinsi Papua (the main part of the island, excluding the Bird’s Head), and Provinsi Papua Barat (centred on the Bird’s Head). Together these are traditionally referred to as West Papua in English (superseding the earlier term Irian Jaya). The term Papua Barat itself translates as ‘West Papua’, and the term ‘Papua’ is also traditionally used for the southern half of the state of Papua New Guinea. To avoid confusion, in this chapter the term ‘Provinsi Papua’ is used to refer to that Indonesian province, while ‘West Papua’ is used to refer to the Indonesian provinces of Papua and Papua Barat together.

10 Hammarstrom and Nordhoff (2012: 25-26) compare the level of documentation of Papuan and Austronesian languages as a region with levels for Africa, Australia, Eurasia, North America, and South America. The figures above compare just the Papuan figures with those for Eurasia. ↩︎

It is likely that with more data and further research, some of these isolates or small groupings will turn out to belong within larger families. Until recently, for example, a putative Lower Mamberamo family of two languages, Warembori and Yoke spoken on the north coast of West Papua, were regarded as Papuan languages showing heavy influence from Austronesian (Donohue 1999). Recent work has shown that they are Papuanized Austronesian languages (Dunn & Reesink this volume; Foley this volume chapter 4.16; Kamholz 2014: 32) 11{ }^{11}. Similarly, Yetfa, classified here as an isolate, may well turn out to be a member of the Sepik family (Foley this volume chapter 3.6.7). There are numerous other such examples. It is probably significant that it is the least documented region, the north coast and highlands of Provinsi Papua, that contains the most isolates - at 14, more than a third of the total number of isolates identified in this volume. With more documentation and comparative work, some of these may be shown to have wider links.

However, the reverse is also true. As more is known about some languages and small groups currently linked to larger families it will transpire that they are in fact unrelated. For example, Laycock and Z’Graggen (1975: 752-753) group together six languages spoken along a tributary of the Sepik River in a Leonard Schultze “family”, named for the tributary on which they are found, claiming that this group forms a branch of the large Sepik family. This is the position taken by Ethnologue (Simons and Fennig 2017). However, Laycock and Z’Graggen’s assessment is based on a very limited data consisting of short wordlists used to group four of the languages (Walio, Pei, Yawiyo and Tuwari) on the one hand, and Baiyamo (a.k.a. Paupe) and Asaba (a.k.a. Duranmin) on the other. Laycock and Z’Graggen join these groups on the basis of possible shared typological features of their classifier systems (Laycock 1973). The linking of these two groups, and their association with the Sepik family, is therefore based on slender evidence. An appraisal of the original data as well as some more recent documentation, particularly on Asaba, leads Foley (this volume chapter 3.8) to conclude that these languages do not belong to the Sepik family at all. Leonard Schultze is accordingly treated as a separate family in this volume. However, linking the two groups into a single family is itself suspect, based as it is on a typological assessment of one area of the grammar. Foley (this volume chapter 3.8) takes the view that the Leonard Schultze languages may turn out to belong to more than one family. Given that the level of cognacy claimed by Conrad and Dye (1975: 13) between Yabio and Baiyamo was 7%7 \%, it is likely that Leonard Schultze itself represents two unrelated families, one containing Asaba and Baiyamo, the other containing the remaining four languages.

In general where a grouping is discussed in more than one chapter of this

- 11{ }^{11} Kamholz (2014: 18,32,141-142) treats the two languages of the putative Lower Mamberamo family, Warembori and Yoke, as each forming a first order subgroup of the Austronesian subgroup South Halmahera-West New Guinea. ↩︎

volume, there is broad agreement. However, there are exceptions, for example the family containing Kaure, where uncertainty again arises from the very limited nature of the available documentation. Two reported lects, Kaure and Narau, certainly belong together (Pawley and Hammarström this volume). Two other languages have also been discussed in relation to the group: Kosare and Kaupari. Documentation of Kapauri in particular is especially limited. Pawley and Hammarström (this volume) are inclined to view proposed links as unsupported in the case of both Kosare and Kapauri. Foley (this volume chapter 4), on the other hand, includes Kosare, and links Kapauri, but regards the link with Kapauri as questionable. The comparative evidence presented by Foley is plausible for Kosare, but much less so for Kapauri, so in this chapter and in Tables 1 and 2 the family is treated as including Kosare, but not Kapauri. To add to the complexity of the situation, Kaure and Narau themselves may well represent a single language. They are reported to be mutually intelligible (Dommel and Dommel 1991: 1-3), and the sole primary source for Narau, a short wordlist (Giel 1959), is regarded by Hammarström (p.c.) as not appreciably different to Kaure. ‘Narau’ is the name of a river now frequented by Kosare and Kapauri speakers (Wambaliau 2006: 1), and the Kaure speakers present there when Giel collected his wordlist appear to have subsequently relocted northwards to villages where ‘Kaure’ data was later collected (see Dommel and Dommel 1993). It is possible that Kaure and Narau are not merely dialects of a single language, but doculects of a single variety. They are treated as belonging to a single language in Table 1, where the Kaure family is taken to consist of Kaure (including Narau) and Kosare. To make the picture still more complex, it is possible that the Kaure family itself is a subgroup of TNG. The paucity of data and complexity of the phylogenetic situation across the New Guinea Area mean that uncertainties of this type are common.

This situation is compounded by the highly endangered status of many languages of the area. For example, Kembra, spoken in northeastern Provinsi Papua, is highly endangered (see Foley this volume chapter 4.9). It was reported as having only 30 speakers in 1991, and described as being very different to the neighbouring languages (Doriot 1991). The only documentation known to exist on this language is a short handwritten wordlist. Not surprisingly, its affiliation is unclear (Foley this volume chapter 4), and is likely to remain so.

In part the high level of endangerment of languages of the area is due to vulnerability arising from very low speaker numbers. The overwhelming majority of the 862 Papuan languages identified here have fewer than 10,000 speakers. Only seven appear to have 100,000 speakers or more. With one exception from Timor-Alor-Pantar, all are probable Trans New Guinea languages, principally from the highlands. 12{ }^{12} Only a further seven languages appear to have more than 50,000 speakers. Four of these are probable Trans New Guinea, along with two

- 12 They are Enga and Huli (both TNG Enga-Kewa-Huli), Melpa and Kuman (both TNG ↩︎

from Timor-Alor-Pantar and one from North Halmahera. 13{ }^{13} Only one Papuan language, Enga (Trans New Guinea, Enga-Kewa-Huli) has more than 200,000 (Foley 2000: 359), with Ethnologue (Simons and Fennig 2017) giving a figure of 230,000 for the year 2000 .

The lack of information on many of the languages of the region means that newly identified languages regularly emerge. For example, Tupper (2007) reports briefly on previously unrecognised Turumsa, a language with 5 elderly speakers in 2002 and now almost certainly extinct. Its speakers were resident in Makapa village in Papua New Guinea’s Western Province, whose inhabitants otherwise speak Dibiyaso, a language that probably belongs to the Trans New Guinea family but whose own phylogenetic position is not fully understood (Pawley and Hammarström this volume 2.3.1.5). However, Turumsa does not appear to be related to Dibiyaso. Tupper (2007) reports 61%61 \% lexical similarities with Doso, but the position of Doso itself is uncertain (see Pawley and Hammarström this volume 2.3.1.5). On the basis of Tupper’s figure for lexical similarity, Hammarström et al. (2016) treat Doso and Turumsa as members of a two language family, and that view is adopted here. However, no materials on Turumsa have been published so it is not possible to test Tupper’s figure, and nothing more is known at this stage.

Another recently identified language, Magi (Daniels 2016), spoken in central Madang province, Papua New Guinea, presents a different picture of the discovery to science of a previously unknown language. While the existence of Turumsa was previously wholly unknown to the outside world, Magi was previously thought to be a dialect of Aisi. Daniels (2016) presents lexical and grammatical evidence that the two varieties are separate languages. Here there is no mystery about the language’s phylogenetic status - it belongs to the Sogeram subgroup of the Madang branch of Trans New Guinea. However, it adds a previously unrecognised subgroup (Aisian) to Sogeram, and adds to the total number of languages spoken in the region. More importantly, it adds an additional witness to the typological and historical situation in New Guinea.

Membership of Trans New Guinea is an area of particular uncertainty. Several versions of the Trans New Guinea hypothesis have been advanced at various times (this history is summarised by Pawley and Hammarström (this volume), see also Pawley (2005)). Pawley and Hammarström discuss a number of subgroups for which evidence of Trans New Guinea membership is relatively strong, and which

- Chimbu-Wahgi), Western Dani (TNG Dani), Ekari (TNG Paniai Lakes), and Western Pantar (Timor-Alor-Pantar).

13 They are Golin and Sinasina (both TNG Chimbu-Wahgi), Mid Grand Valley Dani (TNG Dani), Kamano (TNG Kainantu-Goroka), Bunaq and Makasae (both Timor-Alor-Pantar), and Galela (North Halmahera). Pawley and Hammarström (this volume) cite the Ethnologue figure for Makasae of 102,000. However, Holton and Klamer (this volume) give a probably more accurate figure of 70,000 . ↩︎

therefore are usually treated as belonging within TNG. However, they also discuss a number of phylogenetic groupings and isolates that are of disputed TNG membership or for whom the evidence supporting possible TNG membership is weak (this volume 2.3.2), as well as groups and isolates that have at varying times been assigned to TNG but which on closer inspection lack any evidence currently supporting a link (this volume 2.3.3). All the disputed groups and isolates are treated separately here (see Map 1.1) - only the TNG subgroups for whom evidence is relatively strong (see Table 3) are counted within TNG in Table 1. Each other disputed TNG family and isolate is treated separately. However, several of these may ultimately turn out to be TNG on the basis of further research.

Table 3: Subgroups with strong evidence for TNG membership, with numbers of languages

| Madang | 107 | Dagan | 9 | Kayagaric | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Finisterre-Huon | 62 | Mailuan | 8 | Kolopom | 3 |

| Kainantu-Goroka | 29 | Bosavi | 7 | Kutubu | 3 |

| Ok-Oksapmin | 20 | Koiarian | 7 | Kwalean | 3 |

| Anim | 17 | Mek | 7 | West Bomberai | 3 |

| Chimbu-Wahgi | 17 | East Strickland | 6 | Awin-Pa | 2 |

| Greater Awyu | 17 | Kiwaian | 6 | Duna-Bogaya | 2 |

| Enga-Kewa-Huli | 14 | Goilalan | 5 | Manubaran | 2 |

| Angan | 13 | Paniai Lakes | 5 | Somahai | 2 |

| Dani | 13 | Yareban | 5 | Marori | 1 |

| Greater Binanderean | 13 | Gogodala-Suki | 4 | Wiru | 1 |

| Asmat-Kamoro | 11 | Turama-Kikori | 4 | Total | 431 |

1.6. Conclusion

This volume sets out to present current knowledge of this highly complex linguistic region. Given the paucity of data for many areas of New Guinea we can be sure more languages will emerge as research reveals small languages previously unknown to scholars, and languages previously not recognised as having separate identities. Increased documentation will provide the data needed to support further comparative research requiring revision of the phylogenetic classification of many languages and families. It is likely that some isolates will be demonstrated to belong to a known family, and that some families will transpire to be branches of larger phylogenetic groupings. The reverse is also likely - some languages and families will turn out not to fit where they are currently understood to sit in the region’s phylogenetic landscape, turning out to be isolates or members of newly recognized small families. What is certain is that much more research is needed in this most complex linguistic region.

References

Allen, Jim and James F. O’Connell

2014 Both half right: Updating evidence for dating first human arrivals in Sahul. Australian Archaeology 79: 86-108.

Alpher, Barry, Geoffrey O’Grady and Claire Bowern

2008 Western Torres Strait language classification and development. In: Claire Bowern, Bethwyn Evans and Luisa Miceli (eds.), Morphology and Language History, in Honour of Harold Koch, 15-30. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Capell, Arthur

1969 A survey of New Guinea languages. Sydney: University of Sydney Press.

Conrad, Robert J. and T. Wayne Dye

1975 Some language relationships in the Upper Sepik region of Papua New Guinea. Papers in New Guinea Linguistics 18: 1-35.

Daniels, Don

2016 Magi: an undocumented language of Papua New Guinea. Oceanic Linguistics 55(1): 199-224.

Dommel, Peter R. and Gudrun Dommel

1993 Orang Kaure. In: Etnografi Irian Jaya: panduan sosial budaya, buku satu. 21-75. [Jayapura]: Kelompok Peneliti Etnografi Irian Jaya.

Dommel, Peter R. and Gudrun E. Dommel

1991 Kaure phonology. Workpapers in Indonesian Languages and Cultures 9: 1-68.

Donohue, Mark

2007 The Papuan language of Tambora. Oceanic Linguistics 46(2): 520-537.

Donohue, Mark

1999 Warembori. München: Lincom Europa.

Doriot, Roger E.

1991 6-2-3-4 Trek, April-May, 1991. MS.

Duggan, Ana T., Bethwyn Evans, Françoise R. Friedlaender, Jonathan S. Friedlaender, George Koki, D. Andrew Merriwether, Manfred Kayser and Mark Stoneking

2014 Maternal history of Oceania from complete mtDNA genomes: Contrasting ancient diversity with recent homogenization due to the Austronesian expansion. The American Journal of Human Genetics 94: 721-733.

Flannery, Tim

1995 Mammals of the South-west Pacific and Moluccan islands. Sydney: Reed Books.

Foley, William A.

2000 The languages of New Guinea. Annual Review of Anthropology. 29: 357-395.

Giël, R.

1959 Exploratie Oost-Meervlakte [Exploration of the Eastern Lakes Plain Area]. Nationaal Archief, Den Haag, Ministerie van Koloniën: Kantoor Bevolkingszaken Nieuw-Guinea te Hollandia: Rapportenarchief, 1950-1962, nummer toegang 2.10 .25 , inventarisnummer 13.

Green, Roger C.

1991 Near and Remote Oceania - disestablishing “Melanesia” in culture history. In:

Andrew K. Pawley (ed.), Man and a half: Essays in Pacific anthropology and ethnobiology in Honour of Ralph Bulmer. Auckland: The Polynesian Society. 491−502491-502.

Greenberg, Joseph H.

1971 The Indo-Pacific hypothesis. In: Thomas A. Sebeok (ed.), Current Trends in Linguistics, Vol. 8: Linguistics in Oceania. 808-71. The Hague: Mouton

Hammarström, Harald

2010 Status of least documented language families. Language Documentation & Conservation 4: 177-212.

Hammarström, Harald, Robert Forkel, Martin Haspelmath and Sebastian Bank (eds.)

2016 Doso-Turumsa. Glottolog 2.7. Jena: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

Hammarström, Harald and Sebastian Nordhoff

2012 The languages of Melanesia: Quantifying the level of coverage. In: Nicholas Evans and Marian Klamer (eds.), Melanesian languages on the edge of Asia: Challenges for the 21st Century. 13-33. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.

Hope, Geoffrey S. and Simon G. Haberle

2005 The history of the human landscapes of New Guinea. In: Pawley et al. (eds.), 541−554541-554.

Kamholz, David C.

2014 Austronesians in Papua: Diversification and change in South Halmahera-West New Guinea. PhD thesis: University of California, Berkeley.

Kayser, Manfred

2010 The human genetic history of Oceania: Near and Remote views of dispersal. Current Biology 20(4) DOI 10.1016/j.cub.2009.12.004

Laycock, Donald C.

1973 Sepik languages - checklist and preliminary classification. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics.

Laycock, Donald C. and John A. Z’Graggen

1975 The Sepik-Ramu phylum. In: Stephen A. Wurm (ed.) New Guinea area languages and language study, Volume one: Papuan languages, 731-766. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics.

Lincoln, Peter C.

1978 Reef-Santa Cruz as Austronesian. In: Wurm and Carrington (eds.), 929-967.

Mona, Stefano, Katharina E. Grunz, Silke Brauer, Brigitte Pakendorf, Loredana Castri, Herawati Sudoyo, Sangkot Marzuki, Robert H. Barnes, Jörg Schmidtke, Mark Stoneking and Manfred Kayser

2009 Genetic admixture history of Eastern Indonesia as revealed by Y-chromosome and mitochondrial DNA analysis. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 26(8): 1865-1877. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msp097

Næss, Åshild

2006 Bound nominal elements in Āiwoo (Reefs): A reappraisal of the ‘multiple noun class systems’. Oceanic Linguistics 45: 269-296.

Næss, Åshild and Brenda H. Boerger

2008 Reefs-Santa Cruz as Oceanic: Evidence from the verb complex. Oceanic Linguistics 47: 185-212.

Pawley, Andrew K.

2009 Greenberg’s Indo-Pacific hypothesis: an assessment. In: Bethwyn Evans (ed.), Discovering history through language: papers in honour of Malcolm Ross. 153-180. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics.

Pawley, Andrew

2005 The chequered career of the Trans New Guinea hypothesis: Recent research and its implications. In: Pawley et al. (eds.), 67-108.

Pawley, Andrew K. and Roger C. Green

1973 Dating the dispersal of the Oceanic languages. Oceanic Linguistics 12: 1-67.

Pawley, Andrew, Robert Attenborough, Jack Golson and Robin Hide (eds.)

2005 Papuan pasts. Cultural, linguistic and biological histories of Papuan-speaking peoples. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics.

Ross, Malcolm

2001 Is there an East Papuan phylum? Evidence from pronouns. In: Andrew Pawley, Malcolm Ross, and Darrell Tryon (eds.), The boy from Bundaberg: Studies in Melanesian linguistics in honour of Tom Dutton, 301-321. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics.

Ross, Malcolm and Åshild Næss

2007 An Oceanic origin for Aiwoo, the language of the Reef Islands? Oceanic Linguistics 46: 456-498.

Simons, Gary F. and Charles D. Fennig (eds.)

2017 Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Twentieth edition. Dallas, Texas: SIL International. Online version: http://www.ethnologue.com.

Specht, Jim

2005 Revisiting the Bismarcks: some alternative views. In: Pawley et al. (eds.), 235−288235-288.

Spriggs, Matthew

2011 Archaeology and the Austronesian expansion: where are we now? Antiquity 85(328): 510-528.

Spriggs, Matthew

1997 The Island Melanesians. Oxford: Blackwell.

Summerhayes, Glenn R., Matthew Leavesley, Andrew Fairbairn, Herman Mandui, Judith Field, Anne Ford and Richard Fullagar

2010 Human adaptation and plant use in highland New Guinea 49,000 to 44,000 years ago. Science 330: 78-81.

Tupper, Ian

2007 Endangered languages listing: TURUMSA [tqm]. www.pnglanguages.org/ pacific/png/show_lang_entry.asp?id=tqm

Wambaliau, Theresia

2006 Draft laporan survei pada Bahasa Kosare di Papua, Indonesia [Draft Survey Report on the Kosare Language in Papua, Indonesia]. MS. SIL.

Wurm, Stephen A.

1978 Reef-Santa Cruz: Austronesian, but …! In: Wurm and Carrington (eds.), 9691010 .

Wurm, Stephen A. and Lois Carrington (eds.)

1978 Second International Conference on Austronesian Linguistics: proceedings. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics.

Brought to you by | Purdue University Libraries

Authenticated

Download Date | 12/17/17 2:40 AM