Round, Ground, and Stone: An Analysis of Groundstone Discoidals from Middle and Early Late Fort Ancient Sites (original) (raw)

2020, Archaeology of Eastern North America

Abstract

The research presents a new typology and new regional characteristics of Fort Ancient period groundstone discoidals. Groundstone discoidals are a common artifact type in Middle and early Late Fort Ancient archaeological assemblages; however, little work has been done to analyze and compare this artifact type. Current typologies of Mississippian chunkey stones developed by Perino (1971) and Kelly et al. (1987) do not adequately describe the forms of groundstone discoidals found on Fort Ancient sites. This study presents a morphologically-driven typology for Fort Ancient groundstone discoidals based on observed examples from across the state of Kentucky. The definitions of the typology and the results of a geographical comparison of Fort Ancient groundstone discoidals from three regions in Kentucky are presented.

Figures (25)

Table 1. Sites, number of discs reported, and inclusion in sample. ered from sites in northern Kentucky compared to those recovered from sites in eastern Kentucky. Inorder to present these findings, this article will begin with a brief discussion of previous research conducted on groundstone discoidals in the Fort Ancient area. I will then present descriptions for the typologies followed by a comparison of the groundstone discoidals included in this study.

Table 2. Site name and disc count included in study.

Table 3. Discoidal type distribution by site tics, a short letter code follows each type number. The code features C for concave, F for flat, V for convex, NP for not perforated, PP for partially perforated, and P for perforated. Function was not taken into account when defining these types. In addition to being assigned to a type number based on the typology, groundstone discoidals were also graded on surface smoothness of margins and horizontal surfaces, material type, decoration type, completeness, discoidal diameter, perforation diameter (if applicable), thickness, and weight. Diameter-to-thickness ratios and discoidal diameter-to-perforation ratios were also calculated. Measurements were made in millimeters with digital calipers.

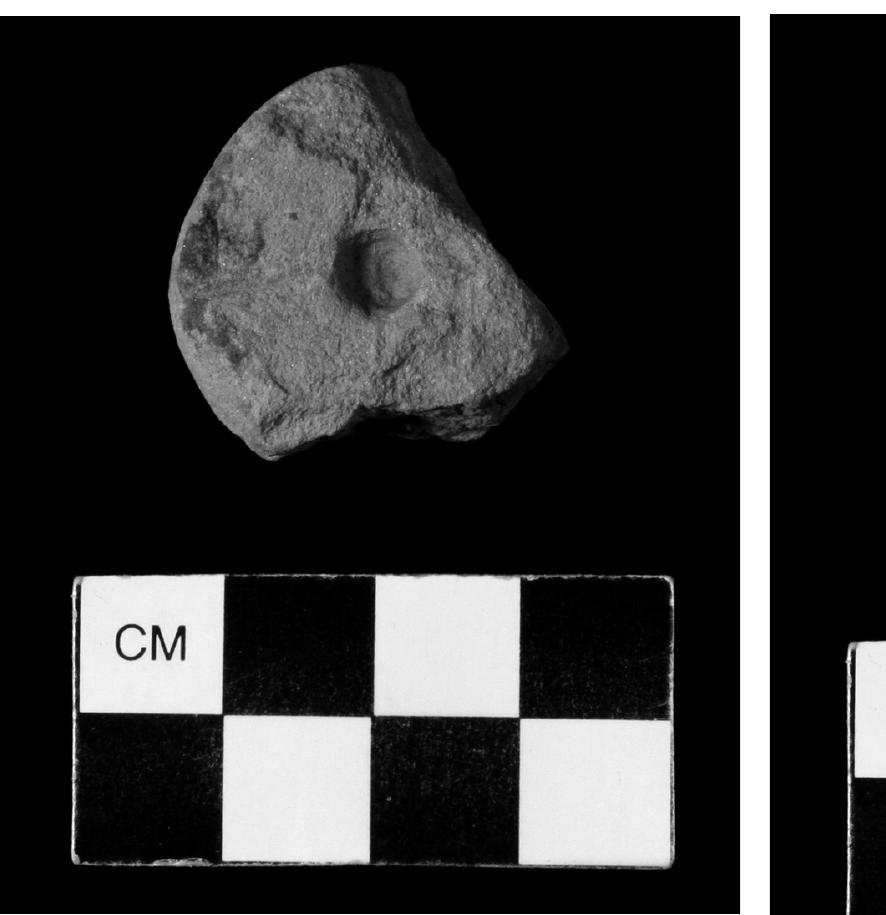

Figure 2. Type 2 (CP) discoidal example. Figure 1. Type 1 (CNP) discoidal example.

TYPE DESCRIPTIONS AND FINDINGS

Figure 3. Type 3 (CPP) discoidal example. Round, Ground, and Stone: An Analysis of Groundstone Discoidals Figure 4. Type 4 (FNP) discoidal example. als have flat sides and no central perforation (Figure 4). There was a total of 161 Type 4 (FNP) discoidals analyzed. They were recovered from the sites of Buckner (n=1), Bedinger (n=3), Kenney (n=6), Fox Farm (n=23), Slone (n=126), Site 15Pi7 (n=1), and northern Kentucky (n=1). These discoidals appear as either whole (n=108) or fragmentary (n=53) specimens. Type 4 (FNP) discoidals range in size from 19.05 to 56.22 mm with an average diameter of 33.67 mm. The diameter of Type 4 (FNP) discoidals ranges from 5.93 mm to 23.77 mm with an average of 13.27 mm. Discoidals in this ype included decorated (n=18) and non-decorated (n=143) pieces. Decoration patterns included circum-incised with drilled holes n=1), lateral incised (n=8), lateral incised and circum-incised n=4), lateral incised with notched edges (n=1), lateral-incised with drilled holes (n=1), only drilled holes (n=2), and unique n=1) specimens. Every type of material type represented in the sample was seen in Type 4 (FNP), including sandstone (n=135), quartzite (n=1), limestone (n=19), hematite (n=2), glacial cobbles n=2), and cannel coal (n=1).

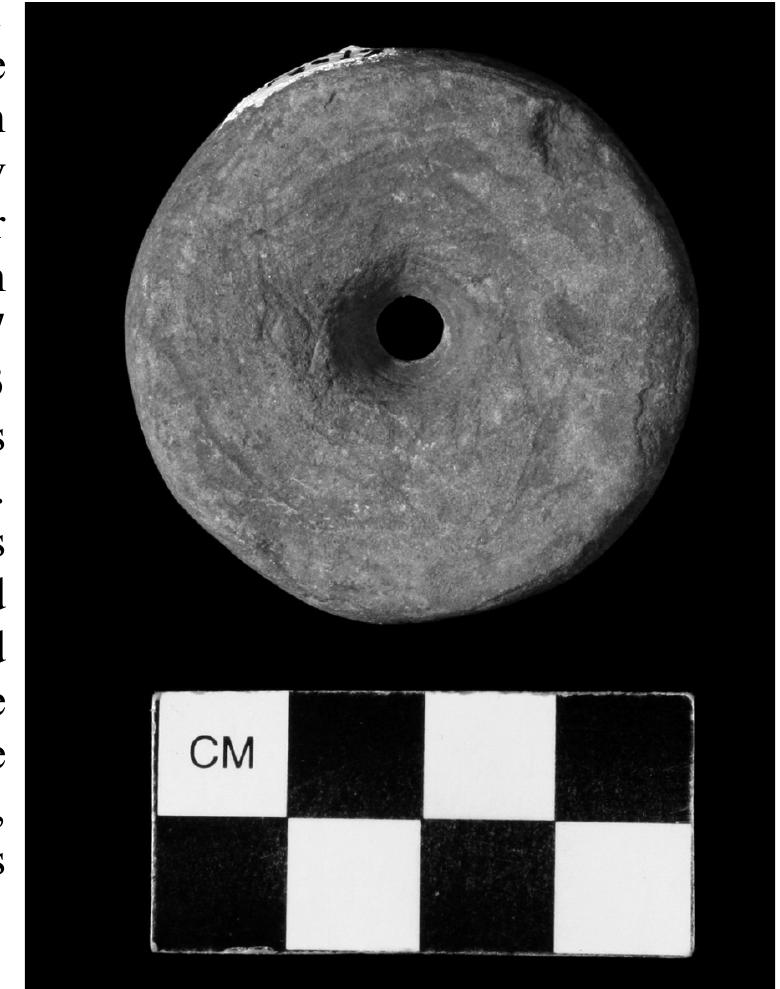

ee wee a I I a ad These discoidals are characterized as being flat on their interior and exterior surfaces and perforated (Figure 5). The type was represented by 15 discoidals from the sites of Kenney (n=3) and Fox Farm (n=12). The specimens are all either whole (n=14) or fragmentary (n=1) pieces of discoidals. Diameters range from 15.99 to 68.96 mm and have an average diameter of 44.51 mm. The thicknesses of this type ranged from 5.66 to 24.33 mm and had an average of 15.09 mm. None were decorated. Discoidals in this type were made from either sandstone (n=13) or limestone (n=2). PISUIeE o. Lype 5 UL) discoldal example.

Figure 7. Type 7 (VNP) discoidal Figure 6. Type 6 (FPP) discoidal example.

Type 8 (VPP) discoidals are convex and partially perforated (Figure 8). Five discoidals in the sample were assigned to this type, and they occurred at the Fox Farm (n=4) and Slone sites (n=1). They appear in the assemblage as whole (n=4) and fragmentary (n=1) pieces. Diameters range from 30.93 mm to 46.99 mm, with an average diameter of 39.24 mm. The range of thicknesses is 12.76 to 20.34 mm, with an average thickness of 15.49 mm. Decoration in Type 8 (VPP) was represented by a single laterally incised piece, whereas the majority was non-decorated (n=4). Material types in the Type 8 (VPP) assemblage consist of only sandstone (n=2) and limestone (n=3) discoidals. example.

Figure 9. Decorated discoidal with circum- incising.

Figure 11. Discoidal with notches and incising.

Round, Ground, and Stone: An Analysis of Groundstone Discoidals SN, After narrowing my sample to these sites due to their geographic location and relative abundance of discoidals, the sample size became 293, with 29 from northern Kentucky, 116 from northeastern Kentucky, and 148 from eastern Kentucky. The variables identified in the regional comparison will follow the same pattern as the variable descriptions. A comparison of types across the study area will first be presented,

Table 5. Number and type of perforation arranged by site ion as a groundstone discoidal that is convex and not perforated. Using the combined frequencies of like-character groundstone discoidals (such as all having perforations or all being concave) can also indicate potential use because the discoidals are following a similar design. Some of these patterns were observed in this type regional comparison. Because he majority of the discoidals in eastern Kentucky are of the same type, they were likely used for the same function. Meanwhile, the lesser representation of Type 2 (CP)’s in northern Kentucky (6.8%, or 2 discoidals) versus the representation in northeastern Kentucky (37% of the assemblage) might indicate a change in physical characteristics due to different functions from the Type 4 (FNP) and Type 1 (CNP) discoidals. These are both evidence of potential use with regard to type.

Table 6. Type of material arranged by region. I OE EEE discoidals were found. In eastern Kentucky, over 90% of the discoidals were made of sandstone, with the next most common material type being limestone, at only 5.4%. The only hematite discoidals analyzed in the entire assemblage were found in eastern Kentucky.

Table 7. Decoration type arranged by region. a, > a” The overwhelming majority of sandstone and limestone as the preferred material types when making these discoidals indicates that these discoidals were likely used for similar purposes, as the same material type could be utilized for most discoidals. This also could be related, however, to the availability of materials, which might explain why glacial cobbles only appear in the northern two regions. Likewise, the presence of hematite discoidals only in eastern Kentucky sites might be related to the availability of resources in the region.

Table 8. Discoidal diameters arranged by region (mm). Round, Ground, and Stone: An Analysis of Groundstone Discoidals

Table 11. Diameter-to-thickness ratios arranged by region.

Table 9. Perforation diameter by region. Table 10. Discoidal thickness by region (mm).

Thickness shows a trending of larger thicknesses as one moves northwest (Table 10). Northern Kentucky had the thickest discoidal of the sample. Its average thickness is almost 1 mm larger than that of Fox Farm and almost 4 mm larger than that of Slone. Slone has the smallest thickness of the sample and the smallest maximum thickness of the three regions. This pattern correlates with the patterns seen between these regions regarding diameter.

Table 12. Weight by region. removed, a clear pattern emerges. In this instance, the lightest discoidal from eastern Kentucky is nearly three times lighter than the lightest discoidal from northeastern Kentucky, which is over three times lighter than the lightest discoidal from northern Kentucky. Although this is the most dramatic difference within the discoidal weights, it does help to reinforce the patterns seen in other data.

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

References (36)

- Bradbury, Andrew P., and Michael D. Richmond 2004 A Preliminary Examination of Quantitative Methods for Classifying Small Triangular Points from Late Prehistoric Sites: A Case Study from the Ohio River Valley. Midcontinental Journal of Archaeology 29(1):43- 61. Breitburg, Emanuel 1992 Vertebrate Faunal Remains. In Fort Ancient Cultural Dynamics in the Middle Ohio Valley, edited by A. Gwynn Henderson, pp. 209-241. Prehistory Press, Madison, Wisconsin.

- Brose, David S. 1978 The Archaeological Investigations of a Fort Ancient Community Near Ohio Brush Creek, Adams County, Ohio. Kirtlandia 34: 1-69.

- Davidson, Michelle M. 2003 Preliminary Mineralogical and Chemical Study of Pre-Madisonville Horizon and Madisonville Horizon Ceramics. Norse Scientist 1:91-102.

- De Boer, Warren R. 1993 Like a Rolling Stone: The Chunkey Game and Political Organization in Eastern North America. Southeastern Archaeology 12(2):83-92.

- Dunnell, Robert C. 1966 Archaeological reconnaissance in the Fishtrap Reservoir, Kentucky, 1966. Ms. On file, Department of Anthropology, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut.

- 1972 The Prehistory of Fishtrap, Kentucky. Publications in Anthropology No. 75. Department of Anthropology, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut.

- Ellis, Laura Elizabeth 2015 Investigating the Orchard Site: A Protohistoric Fort Ancient Site in West Virginia. Published thesis, Indiana University of Pennsylvania, Indiana, Pennsylvania.

- Gehlbach, D.R. 2010 Antiquarian Research at the Feurt Site: A Major Fort Ancient Community in Scioto County Ohio. Ohio Archaeologist 60(1): 15-17.

- 2011 Some Highly Engraved Fort Ancient Discoidals. Ohio Archaeologist 61(1):48-49.

- George, Richard L. 2001 Of Discoidals and Monongahela: A League of their Own? Archaeology of Eastern North America 29:1-18.

- Griffin, James B. 1943 The Fort Ancient Aspect: Its Cultural and Chronological Position in Mississippi Valley Archaeology. University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor.

- Griffin, James B. (editor) 1966 Archaeology of the Eastern United States. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, Illinois. Hanson, Lee H. Jr. 1966 The Hardin Village Site. Studies in Anthropology, No. 4. University of Kentucky Press, Lexington. Hanson, Lee H., Jr. 1975 The Buffalo Site: A Late 17th Century Indian Village Site (46Pu31), in Putnam County, West Virginia. Report of Archaeological Investigations, no. 5. West Virginia Geological Survey, Morgantown.

- Hanson, Lee H., Jr., Robert C. Dunnell, and Donald L. Hardesty 1964 The Slone Site, Pike County, Kentucky. Ms. On file at the National Park Service, Southeastern Region, Richmond Virginia.

- Henderson, A. Gwynn (editor) 1992 Fort Ancient Cultural Dynamics. Prehistory Press, Madison, Wisconsin.

- Henderson, A. Gwynn 2008 Fort Ancient Period. In The Archaeology of Kentucky: An Update, volume 2, edited by David Pollack, pp. 739- 902. Kentucky Heritage Council, Frankfort.

- Henderson, A. Gwynn, Cynthia E. Jobe, and Christopher A. Turnbow 1986 Indian Occupation and Use in Northern and Eastern Kentucky During the Contact Period. Report on file, Kentucky Heritage Council, Frankfort.

- Hockensmith, Charles D. 1984 The Johnson Site: A Fort Ancient Village in Scott County, Kentucky. In Late Prehistoric Research in Kentucky, edited by David Pollack, Charles Hockensmith, and Thomas Sanders, pp. 85-104. Kentucky Heritage Council, Frankfort.

- Hodge, F.W. 1960 Handbook of American Indians North of Mexico. 2 vols. Pageant Books, New York.

- Hooten, Ernest A., and Charles C. Willoughby 1974 [1920] Indian Village Site and Cemetery near Madisonville, Ohio. Peabody Museum of America Archaeology and Ethnology, Papers 8(1). Harvard University, Cambridge.

- Kelly, John E., Steven J. Ozuk, and Joyce A. Williams 1990 The Range Site 2: The Emergent Mississippian Dohack and Range Phase Occupations. American Bottom Archaeology, FAI-270 Site Reports No. 20. University of Illinois Press, Urbana. Link, Adolph W. 1980 Discoidals and Problematic Stones from Mississippian Sites in Minnesota. Plains Anthropologist 25(90):343- 352.

- Marwitt, John, Brenda Davis, Stephen Batug, Virginia Albaneso, Thomas Yocum, and Richard Stallings 1984 Test Excavations at the Island Creek Village Site (33AD25). Ms. On file, U.S. Army Corp of Engineers, Huntington District, Huntington, West Virginia.

- Mayer-Oakes, William J. 1955 Prehistory of the Upper Ohio Valley. Annals of the Carnegie Museum 34. Pittsburgh, PA. Mills, William C. 1917 Fuert Mounds and Village Site. Ohio History 26(3):305-449. Moody, Robert 1959 The Buckner Site, Site BB12, Bourbon County, Kentucky. Ms. on file, Office of State Archaeology, University of Kentucky, Lexington.

- Oehler, Charles 1973 Turpin Indians. Popular Publication Series No. 1. Cincinnati Museum of Natural History, Cincinnati, Ohio. Perino, Gregory H. 1971 The Mississippian Component at the Schild Site (No. 4), Greene County, Illinois. In Mississippian Site Archaeology in Illinois I. Site Reports from the St. Louis and Chicago Areas. Illinois Archaeological Survey, Inc. Bulletin No. 8. University of Illinois Press, Urbana.

- Pollack, David, and A. Gwynn Henderson 2000 Insights into Fort Ancient Culture Change: A View from South of the Ohio River. In Cultures Before Contact: The Late Prehistory of Ohio and Surrounding Regions, edited by Robert A. Genheimer, pp. 194-227. Ohio Archaeological Council, Columbus.

- Pollack, David, and Kary L. Stackelbeck 1999 Bedinger Site (15Be486) National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form. On file, Kentucky Heritage Council, Frankfort.

- Prufer, Olaf H., and Orrin C. Shane 1970 Blain Village and Fort Ancient Tradition in Ohio. Kent State University Press, Kent, Ohio. Rafferty, Janet Elizabeth 1974 The Development of the Fort Ancient Tradition in Northern Kentucky. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, Department of Anthropology, University of Washington, Seattle.

- Railey, Jimmy A. 1990 Chipped Stone Artifacts. In Continuity and Change: Fort Ancient Cultural Dynamics in Northeastern Kentucky, edited by A. Gwynn Henderson, pp. 173-215. Kentucky Heritage Council, Frankfort.

- Railey, Jimmy A. 1992 Chipped Stone Artifacts. In Fort Ancient Cultural Dynamics in the Middle Ohio Valley, edited by A. Gwynn Henderson, pp. 137-169. Monographs in World Archaeology No. 8. Prehistory Press, Madison, Wisconsin. Rossen, Jack 1992 Botanical Remains. In Fort Ancient Cultural Dynamics in the Middle Ohio Valley, edited by A. Gwynn Henderson, pp. 189-208. Prehistory Press, Madison, Wisconsin.

- Schneider, Roger Lee 1966 A Preliminary Study of a Fort Ancient Site. Unpublished Masters Thesis, Department of Education, Wittenberg University, Springfield, Ohio.

- Schock, Jack M. 1975 Archaeological Survey of the Various Alternates for the Relocation of the Louisa-Fort Gray Bridge. Western Kentucky University, Bowling Green.

- Sharp, William E., and David Pollack 1992 The Florence Site Complex: Two Fourteenth-Century Fort Ancient Communities in Harrison County, Kentucky. In Current Archaeological Research in Kentucky, Volume Two, edited by David Pollack and A. Gwynn Henderson, pp. 183-218. Kentucky Heritage Council, Frankfort.

- Smith, Harlan I. 1910 The Prehistoric Ethnology of a Kentucky Site. Anthropological Papers 6(2):173-234.

- Turnbow, Christopher A., and William E. Sharp 1988 Muir: An Early Fort Ancient Site in the Inner Bluegrass. Archaeological Report No. 165. Program for Cultural Resource Assessment, University of Kentucky, Lexington, Kentucky.

- Turnbow, Christopher A. 1984 The Dunn Village Site (15CP40) Survey Form. Ms. On file, Office of State Archaeology, Lexington, Kentucky. Turnbow, Christopher A. 1992

- Ground, Pecked, and Battered Stone Artifacts. In Fort Ancient Cultural Dynamics, edited by A. Gwynn Henderson, pp. 171-179. Prehistory Press, Madison, Wisconsin.

- Winchell, N.H. (editor) 1911 The Aborigines of Minnesota, A Report based on the collections of Jacob V. Brower, and on the Field Surveys and Notes of Alfred J. Hill and Theodore H. Lewis. Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul. Wohlgemuth, Richard 1981 An Archaeological Study for the Proposed Bracken Creek Apartment Complex Near Augusta, Bracken County, Kentucky. Granger Associates, Louisville, Kentucky.