Exchange rates and casualties during the first world war (original) (raw)

2004, Journal of Monetary Economics

https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JMONECO.2004.02.001

Sign up for access to the world's latest research

checkGet notified about relevant papers

checkSave papers to use in your research

checkJoin the discussion with peers

checkTrack your impact

Abstract

for helpful conversations. I thank Richard Burdekin, Marc Weidenmier, and seminar participants at Yale and Rutgers for constructive comments. The views expressed herein are those of the author and not necessarily those of the National Bureau of Economic Research.

Figures (15)

Figure 1: Monthly exchange rates normalized to have a mean of zero and a standard deviation of one.

Figure 2: Daily exchange rates normalized to have a mean of zero and a standard deviation of one.

and Nf; is a5 X 1 vector of martingale differences sequences whose elements satisfy assume each country-specific factor is serially correlated: and lags, with mean zero and variance one. Let {v,} denote the 5 x 1 vector of country-specific factors. I

Next, let E[Y|X] denote the linear least squares projection of Y onto X, and let K, and , denote the

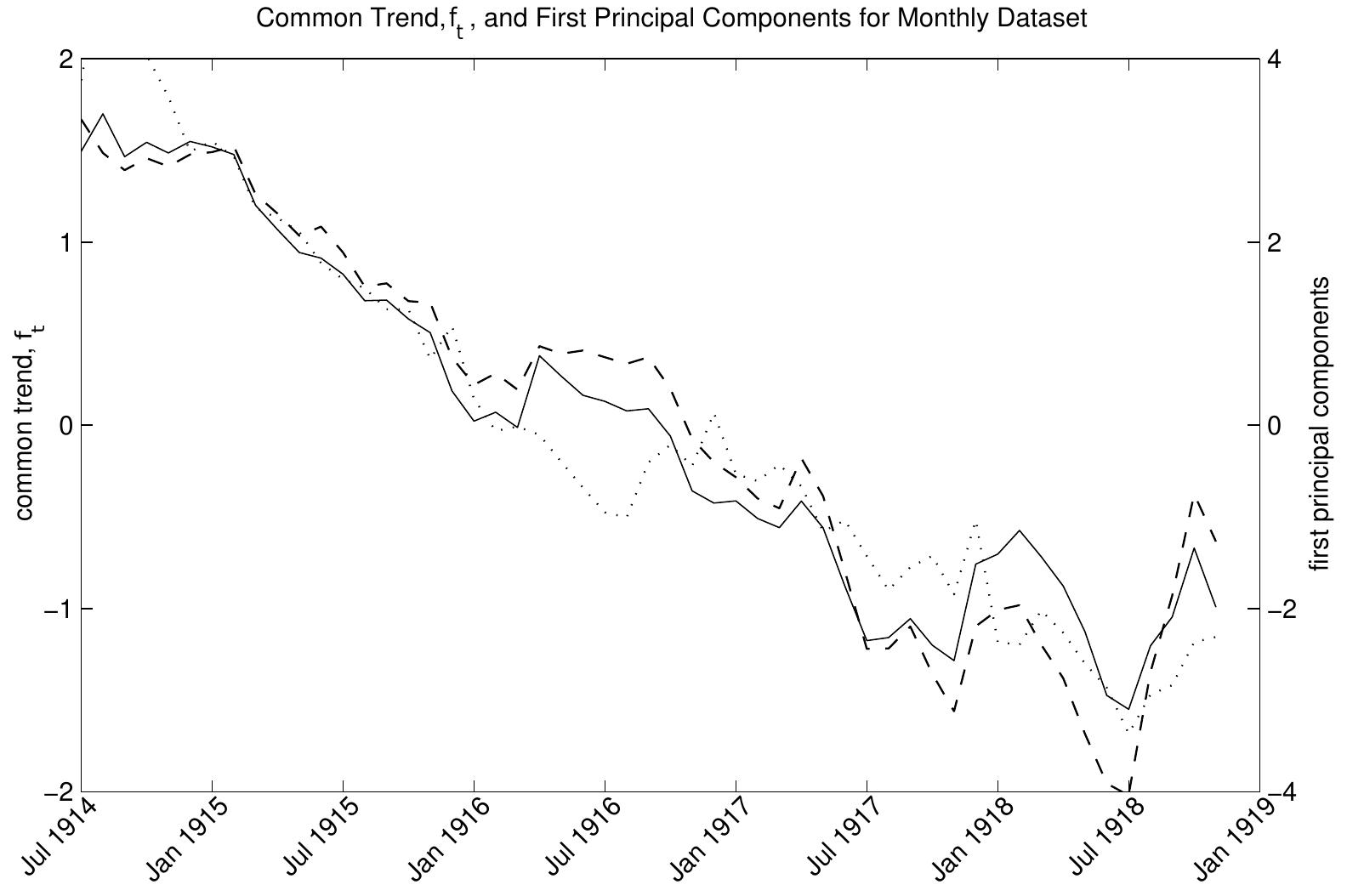

Figure 3: The one-step-ahead forecast of the common trend, f,, (solid line, left axis) for the five-country model, first principal component of the monthly exchange rates (dashed line, right axis), and first principal component of the notes in circulation (dotted line, right axis).

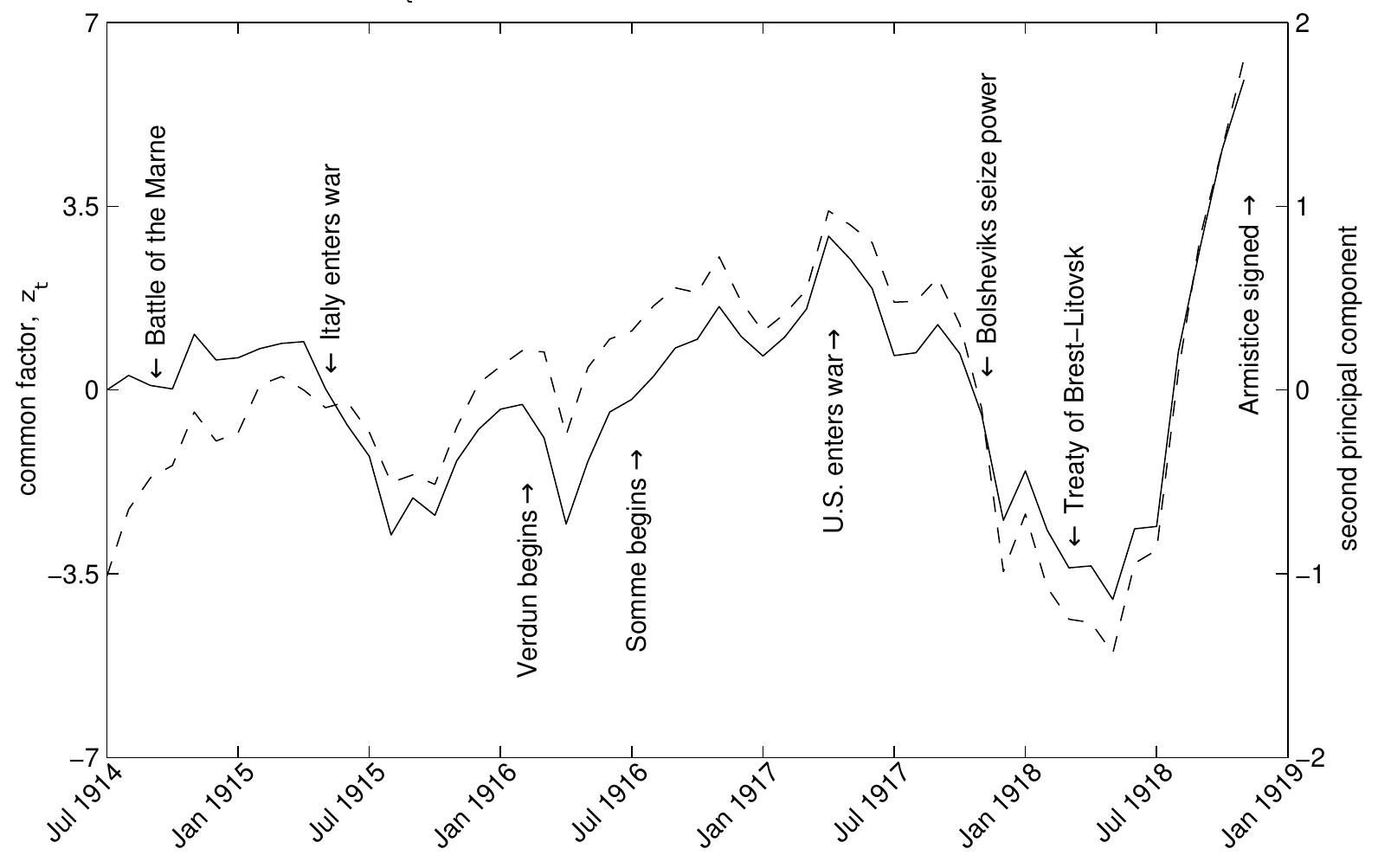

Common Factor, z, , and Second Principal Component for the Monthly Exchange Rates t? Figure 4: The one-step-ahead forecast of the common factor, 2,, (solid line, left axis) and the second principal component (dashed line, right axis) for the five-country monthly model.

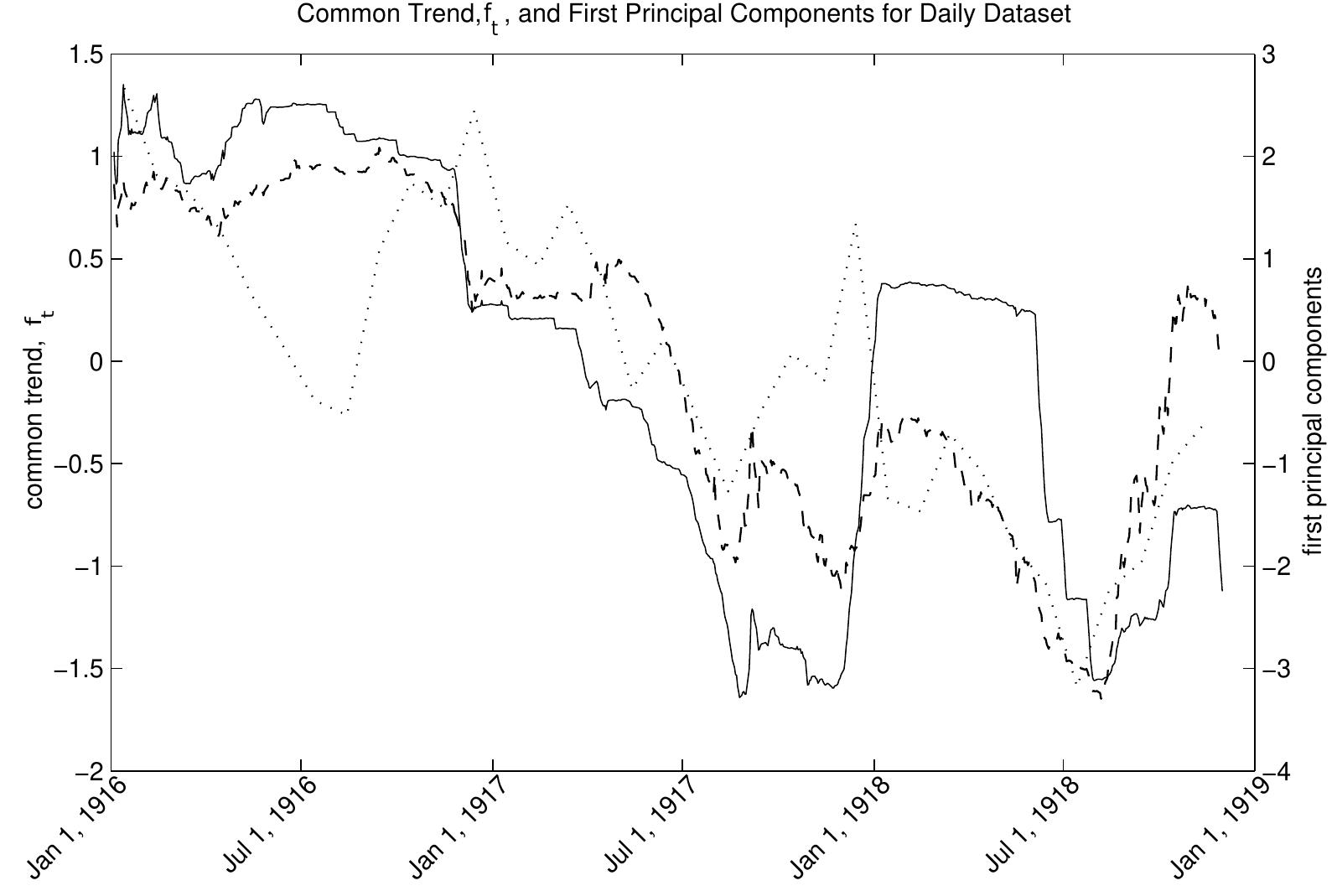

Figure 5: The one-step-ahead forecast of the common trend, f,, (solid line, left axis) for the three-country model, first principal component of the monthly exchange rates (dashed line, right axis), and first principal component of the notes in circulation (dotted line, right axis).

Figure 6: The one-step-ahead forecast of the common factor, 2,, (solid line, left axis) and the second principal component (dashed line, right axis) for the three-country daily model.

Figure 7: British and German soldiers killed and wounded and French total casualties by month.

Figure 8: British and German soldiers missing and taken prisoner by month.

Related papers

The economics of World War I: A comparative quantitative analysis

Journal of Economic History, 2006

We draw on the experience of the major combatant countries in World War I to analyse the role of economic factors in determining the outcome of the war and the effects of the war on subsequent economic performance. We demonstrate that the degree of mobilisation for war can be explained largely by differences in the level of development of each country, leaving little room for other factors that feature prominently in narrative accounts, such as national differences in war preparations, war leadership, military organisation and morale. We ...

2005

This unique volume offers a definitive new history of European economies at war from 1914 to 1918. It studies how European economies mobilized for war, existing economic institutions stood up under the strain, economic development influenced outcomes, and wartime experience influenced postwar economic growth.

The Economics of World War I: an Overview

2004

During the twentieth century the world experienced two deadly global wars followed by a “cold war” of unparalleled expense and danger. World War I opened this brutal epoch. To many who took part the experience was little less than apocalyptic; it seemed like an end, not a beginning. They saw it as putting a stop to history, progress, and civilisation. They called it the “Great War”. They did not know that it would be followed twenty years later by World War II and that the second war would be greater and more dreadful than the first.

From the Eighty Years War to the Second World War. New Perspectives on the Economic Efffects of War

Tijdschrift voor sociale en economische geschiedenis, 2014

Most historians used to regard war as economically destructive. They focused on short-term damage to the economy, guided by archives that were dominated by documents related to reparation demands and offi cial statistics that did not take into account the black market and the rerouting of trade. Gradually, scholars began to acknowledge the positive role played by wartime stimuli with regard to state fi nances, innovative management and new industries. Wartime expenditure proved to have been an impetus for domestic production and demand. Wartime economic downturns often turned out to have been infl uenced by prewar economic trends. Over the last hundred years, the Eighty Years War, the Napoleonic Wars and the Second World War have all received new interpretations, as historians have gathered new data and shifted their focus to the effi ciency of governments and redistributive economic eff ects.

War Finance | International Encyclopedia of the First World War (WW1)

2018

The Great War required war-making states to mobilize and sustain the financial resources for a global war on an unprecedented scale. What made war finance during the conflict so special is that this challenge had never been confronted in a world economy as large, deeply interconnected, and sophisticated as that which existed in 1914. This article outlines the monetary politics of the global “system” of war finance. It will incorporate perspectives on national economies, but integrates these to sketch the international and transnational aspects of financing the war. The article sets out the basic elements of the pre-war financial system and its global dynamics; examines the different modes of war finance adopted by the belligerents; considers the Central Powers and the Entente as financial alliances operating in the global monetary system; describes the interaction of public and private entities; and surveys the long-term consequences of war finance on the world economy.

Exchange rates, money, and relative prices: The dollar-pound in the 1920s

Journal of International Economics, 1980

This paper applies the analytical framework of the monetary approach to exchange rate determination to the analysis of the Dollar/Pound exchange rate during the first part of the 1920's. The analysis uses monthly data up to the return of Britain to gold in 1925. The equilibrium exchange rate is shown to be influenced by both real and monetary factors which operate through their influence on the relative demands and supplies of monies. Special attention is given to examination of the relationship between exchange rates and the relative price of traded to non-traded goods. In the empirical work the prices of traded goods are proxied by the wholesale price indices and the prices of non-traded are proxied by wages. One of the key findings of the paper is the estimate of the elasticity of the exchange rate with respect to the relative price of traded to non-traded goods. This elasticity is estimated with high precision and is shown to be .415 which provides an independent measure of the relative share of spending on non-traded goods. This estimate is consistent with other estimates obtained in studies of expenditure shares. The paper concluded with a dynamic simulation which indicates the satisfactory quality of the predective ability of the model. This paper applies the monetary approach to exchange rate determination to the analysis of the monthly Dollar/Pound exchange rate duingthe period preceeding the return of Britain to Gold in 1925. The analytical framework emphasizes that the exchange rate is influenced by real and ntrnetary factors.

In this article, we introduce and utilize a new dataset that provides battle- and war- level Loss Exchange Ratios (LERs) for combatant states involved in multilateral wars between 1816 and 1990.The battle-level data provide an alternative to the widely used, but problematic, HERO/CDB-90 data set on battle outcomes. To demonstrate the utility of the new data, we weigh in on the debate over democratic military effective- ness arguments by replicating models by Reiter and Stam (2002, 2009) and Downes (2009), finding that, when effective- ness is measured using LERs, democracies do not have an edge over their non-democratic counterparts.

Globalizing the History of the First World War: Economic Approaches

The Historical Journal, 2021

This historiographical review offers an overview of new approaches to the global history of the First World War. It first considers how, over the last decade, there has been a move to emphasize the war's imperial dimensions: in reconsiderations of the war in Africa, the experience of soldiers and workers from across Europe's colonial empires, and the German ‘global strategy’ of fomenting unrest within the Allied empires. It then suggests that new global histories of the First World War give further attention to its economic aspects, particularly in two ways: first, by recovering understudied global financial aspects of the war, including the effects of the 1914 financial crisis and wartime inflation on economies and societies far outside of Europe; and second, by investigating wartime histories of primary production, both in colonial territories and sovereign states in Latin America, Africa, and Southeast Asia. It argues that these approaches can offer an important correctiv...

Related topics

Cited by

The economic effects of violent conflict: Evidence from asset market reactions

Journal of Peace Research, 2010

This article studies the effects of conflict onset on asset markets applying the event study methodology. The authors consider a sample of 101 internal and inter-state conflicts during the period 1974—2004 and find that a sizeable fraction of them has had a significant impact on stock market indices, exchange rates, oil and commodity prices. This fraction is inconsistent with pure chance, that is, with the selected probability of type-I errors in our tests of statistical significance. The results suggest that, on average, national stock markets are more likely to display positive than negative reactions to conflict onset. When the authors distinguish between internal and inter-state conflicts, they find that the fraction of significant results is higher for international conflicts. When the authors classify events according to the region where they occur, they find that Asia and the Middle East are the regions where conflicts tend to have the strongest effects. Finally, the article ...

Market anticipations of conflict onsets

Journal of Peace Research, 2017

Does the recurrence of wars suggest that we fail to recognize dangerous situations for what they are, and are doomed to repeat the errors of the past? Or rather that policymakers correctly anticipate the consequences of their actions but knowingly choose conflict? Unfortunately, little is known about how well wars are anticipated. Do conflicts tend to come as a surprise? I estimated the risk of war as perceived by contemporaries of all interstate and intrastate conflicts between 1816 and 2007. Using historical financial data of government bond yields, I find that market participants tend to underestimate the risk of war prior to its onset, and to react with surprise immediately thereafter. This result illustrates how conflict forecasts can be self-fulfilling or self-defeating. Present predictions may affect future behavior, such that wars may be less likely to occur when they are predicted, but more likely when they are not. I also show that the forecasting record has not improved o...

Scandinavian Economic History Review, 2018

The participation of the Ottoman Empire in the First World War caused economic disruptions, huge budget deficits, surmounted inflation rates and excessive depreciation of Lira, the Ottoman currency. Based on the value of Lira against the currencies of Switzerland, Netherlands, Sweden that were not in the war, we focus on the effects of news about the war on the foreign exchange rates at the İstanbul bourse from 1918 to 1919. Our results signify some dates, which match the announcements of the armistices and peace meetings, heralding continuous depreciation of Lira. Thus, the findings support the presence of an expectation on the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire with the peace, marked by the escalation of the loss in trust for the Lira and the power of the state in foreign exchange interventions.

Related papers

War and exchange rate valuation

The Economics of Peace and Security Journal, 2009

This article investigates the extent to which the dominance of the United States dollar as an international currency has been contingent on American diplomacy rather than the prosecution of expensive wars. Four wars are examined, the Korean war (1950-1953), the Vietnam war (1964-1975), the Persian Gulf war (1990-1991), and the Iraq war (2003-present). The historical performance of the dollar is examined in times of war and peace, and the Box-Jenkins forecasting algorithm is employed to make a short-term projection of the dollar coinciding with the Iraq war. The price of gold is used as a measure of the value of the U.S. dollar and investor confidence in the dollar during times of war and peace. The empirical evidence shows a short-term depreciation of the U.S. dollar coinciding with the Iraq war, which is not atypical of the value of the U.S. dollar in a time of war. Problems with the value of the U.S. dollar in times of war lead to the exploration of alternative forms of money, whi...

508 EHA Abstracts The Long-Term Impact of the Thirty Years War : What Grain Price Data Reveal

2011

s of Papers Presented at the Annual Meeting SESSION 1A: BOOMS AND BUSTS IN THE LONG RUN The Collapse of the Continental Dollar: The Turning Point and Its Causes, An Alternative History of Financing the American Revolution, 1775 1781 An alternative history of the continental dollar is constructed from the original laws passed by Congress. The continental dollar was a zero-interest bearer bond, not a fiat currency. The public could redeem it at face value in specie from the National Treasury at fixed future dates. How, when, and where the public was informed of this is traced through available broadsides and newspapers. Being a zero-interest bearer bond, a continental dollar’s current value was the reduction off its face value discounted back from its future redemption date. Discounting must be separated from depreciation to determine when the continental dollar collapsed. There was no depreciation before 1779, only discounting. Congress’ ex post facto law of 14 January 1779 that alte...

Until it's over, over there: the US economy in World War I

The Economics of World War I, 2005

The process by which the US economy was mobilized during World War I was the subject of considerable criticism both at the time and since. Nevertheless, when viewed in the aggregate the degree of mobilization achieved during the short period of active US involvement was remarkable. The United States entered the war in 1917 having made only limited preparations. In 1918 the armed forces were expanded to include 2.9 million sailors, soldiers, and marines; 6 percent of the labor force in the 15 to 44 age bracket. Overall in 1918, one fifth or more of the nation's resources was devoted to the war effort. By the time the Armistice was signed in 1919 a profusion of new weapons was flowing from American factories. This essay describes how mobilization was achieved so quickly, including how it was financed, and some of the long-term consequences.

Exchange Rates, Prices and Money: Lessons from the 1920s

1980

The experience with flexible exchange rates during the 1920's has proven to be extremely important in shaping out current thinking about the operation of floating rates regime. This paper summarizes the results of a comparative empirical study of the~0peration of flexible exchange rates during the 1920's under both the hyperinflationary conditions (based on the experience of Germany) and under "normal".. conditions (based on the experience of Britain, the U.S., and France). The three issues that are discussed are (i) the efficiency of the foreign exchange market which is analyzed by examining the relationship between spot and forward exchange rates; (ii) the relationship between exchange rates and prices which is analyzed by examining aspects of the purchasing power parity doctrine; and (iii) the determinants of exchange rates which is analyz:ed by examining the relationship between exchange rates, money and expectations.

Reducing Risks in Wartime Through Capital-Labor Substitution: Evidence from World War II

2014

Reducing Risks in Wartime Through Capital-Labor Substitution: Evidence from World War II * Our research uses data from multiple archival sources to examine substitution among armored (tank-intensive), infantry (troop-intensive), and airborne (also troop-intensive) military units, as well as mid-war reorganizations of each type, to estimate the marginal cost of reducing U.S. fatalities in World War II, holding constant mission effectiveness, usage intensity, and task difficulty. If the government acted as though it equated marginal benefits and costs, the marginal cost figure measures the implicit value placed on soldiers' lives. Our preferred estimates indicate that infantrymen's lives were valued in 2009 dollars between $0

Exchange Rates and Economic Recovery in the 1930s

The Journal of Economic History, 1985

Currency depreciation in the 1930s is almost universally dismissed or condemned. This paper advances a different interpretation of these policies. It documents first that depreciation benefited the initiating countries. It shows next that there can be no presumption that depreciation was beggar-thy-neighbor. While empirical analysis indicates that the foreign repercussions of individual devaluations were in fact negative, it does not imply that competitive devaluations taken by a group of countries were without mutual benefit. To the contrary, similar policies, had they been even more widely adopted and coordinated internationally, would have hastened recovery from the Great Depression.

The socio-economic relations of warfare and the military mortality crises of the Thirty Years' War

Medical history, 2001

who acted as my guide to and translator of the UK. German language sources used in this study. All responsibility for the statements made here I wish to record my thanks to John Chartres for remains with the author. his encouragement and to Sue Bowden for her unfailing critical support and practical help, to the editors and referees of this journal for 'M W Flinn, The European demographic stimulating comment and advice, to the Nuffield system 1500-1820, Brighton, Harvester Press, Foundation for financial support (reference SOC/ 1981, p. 53.

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

References (33)

- Anderson, Theodore (1984) An Introduction to Multivariate Statistical Analysis New York: John Wiley and Sons.

- Anderson, Evan, Lars Hansen, Ellen McGrattan, and Thomas Sargent (1996) "Mechanics of Forming and Estimating Dynamic Linear Economies," in H. Amman et al., eds. Handbook of Computational Economics, Vol 1, Amsterdam: Elsevier.

- Barro, Robert (1979) "On the Determination of the Public Debt," Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 87, (October), pp. 940-971.

- Beveridge, William (1928) British Food Control, London: Oxford University Press.

- Bogart, Ernest (1921) War Costs and Their Financing, New York: D. Appleton and Company.

- Bordo, Michael, and Eugene White (1991) "British and French Finance During the Napoleonic Wars," in Bordo and Capie, eds. Monetary Regimes in Transition, Cambridge, Cambridge Univer- sity Press.

- Bordo, Michael, and Finn Kydland (1995) "The Gold Standard As a Rule: An Essay in Exploration," Journal of Economic History, Vol. 32, pages 423-464.

- Brown, William (1940) The International Gold Standard Reinterpreted, 1914-1934 New York: Na- tional Bureau of Economic Research.

- Brown, William, and Richard Burdekin (2000) "Turning Points in the U.S. Civil War: A British Perspective," Journal of Economic History, Vol. 60. pages 216-231.

- Bulletin de la Statistique General de la France, various issues 1914-1919.

- Burnett, Phillip (1965) Reparations at the Paris Peace Conference from the Standpoint of the Ameri- can Delegation New York: Columbia University Press.

- Dupuy, Trevor, and Gay Hammerman (1967) Stalemate in the Trenches: November, 1914 -March, 1918, New York: Franklin Watts, Inc.

- Dupuy, Trevor (1977) A Genius for War: The German Army and General Staff, 1807-1945, Engle- wood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall Inc.

- Fayle, C. Ernest (1927) The War and the Shipping Industry, London: Oxford University Press.

- Federal Reserve Bulletin, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System: Washington DC, May 1, 1918.

- Federal Reserve Bulletin, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System: Washington DC, Jan- uary, 1920.

- Ferguson, Niall (1998) The Pity of War, London: Penguin Press.

- Frey, Bruno, and Marcel Kucher (1997) "Bond Values and World War II Events," manuscript, Insti- tute of Empirical Economic Research at the University of Zurich.

- Gilbert, Martin (1994) The First World War: A Complete History, New York: Henry Holt and Co.

- Kuczynski, R. R. (1923) "German Taxation Policy in the World War," Journal of Political Economy, Vol 31, pages 763-789.

- Larcher, Lieutenant-Colonel (1934) "Donnees Statistiques Sur Les Forces Francaises 1914-1918" Revue Militaire Francaise, No 156, (June), pp. 351-363.

- McCandless, George (1996) "Money, Expectations, and the Civil War," American Economic Review, Vol. 86, (June), pp. 661-671.

- Mitchell, Wesley (1903) A History of the Greenbacks Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

- Offer, Avner (1989) The First World War: An Agrarian Interpretation New York: Oxford University Press.

- Roll, Richard (1972) "Interest Rates and Price Expectations During the Civil War," Journal of Eco- nomic History, Vol. 32, pages 476-498.

- Swiss Bank Corporation (1918) Revue Economique et Financiere Suisse, 1914-1917.

- Swiss Bank Corporation (1919) Revue Commerciale et Industrielle Suisse, 1914-1918.

- Swiss Bank Corporation (1920) La Situation Economique et Financiere de la Suisse, 1919.

- Taylor, A.J.P. (1980) The First World War: An Illustrated History, New York: Perigee Books.

- War Office (1922) Statistics of the Military Effort of the British Empire During the Great War, Lon- don: H.M. Stationery Office.

- Weidenmier, Marc (1999) Financial Aspects of the American Civil War: War News, Price Risk, and the Processing of Information, unpublished Ph.D. dissertation. University of Illinois.

- Willard, Kristen, Timothy Guinnane, and Harvey Rosen (1996) "Turning Points in the Civil War: Views from the Greenback Market," American Economic Review, Vol. 86, pp. 1001-1018.

- Young, John (1925) European Currency and Finance, prepared for the United States Senate Com- mission on Gold and Silver Inquiry, Government Printing Office, Washington DC.

![Next, let E[Y|X] denote the linear least squares projection of Y onto X, and let K, and , denote the](https://figures.academia-assets.com/99330886/figure_004.jpg) ](

](