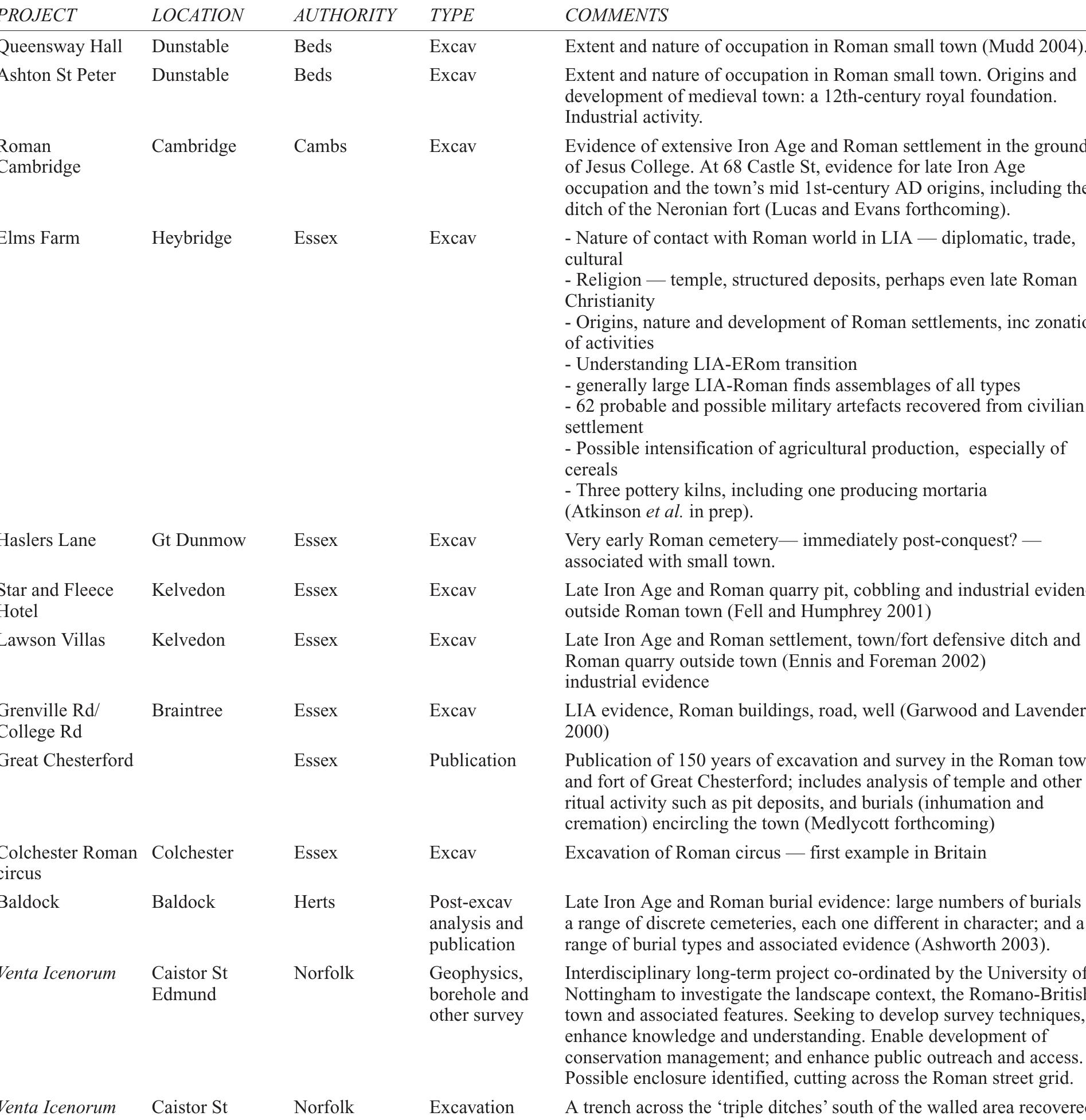

Cropmarks at hopton, norfolk, plotted from aerial (original) (raw)

Figure 10 Cropmarks at Hopton, Norfolk, plotted from aerial photographs. Copyright Norfolk County Council/NMP

Related Figures (80)

Frontispiece: the Norfolk Rapid Coastal Zone Assessment Survey team recording timbers and ballast from the wreck of The Sheraton on Hunstanton beach, with Hunstanton cliffs and lighthouse in the background. Photo: David Robertson, copyright NAU Archaeology

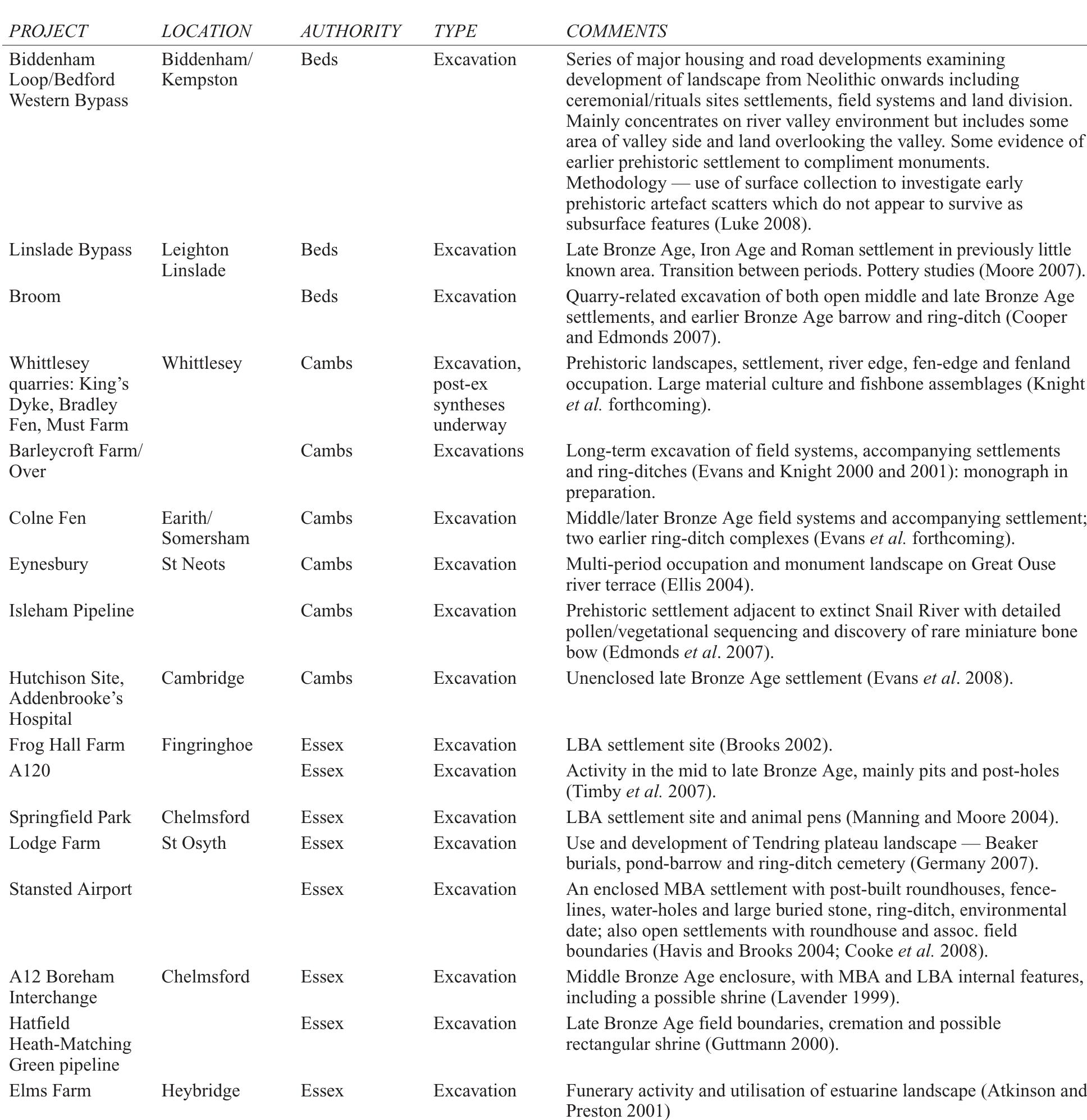

Reconstruction drawing courtesy of the Ancient History of Britain Project / John Sibbick The Wash River project aimed to characterise the known archaeological materials from the gravels of the Washland Rivers of Cambridgeshire, that is the Cam, Nene, Granta and Ouse, in order to update the HER and inform archaeological advice related to mineral extraction Further work has been undertaken on the Palaeolithic resource at Caddington, Gaddesden Row, Barnham, Elveden (Ashton et al. 1999), Santon Downham, High Lodge, Foxhall Road, and Hoxne. Both studies include strategy documents. The Portable Antiquities Scheme has provided an opportunity for the chance recovery of flint artefacts to be recorded. 122 Palaeolithic and 1427 Mesolithic artefacts have been recorded by this means between 1997 and 2007).

The archaeological survey of mineral extraction sites around the Thames Estuary (Essex County Council and Kent County Council 2004) included extant and former mineral sites in the Thurrock/Dartford area. The outputs of this project included a range of GIS layers, incorporating the results of specialist studies (including geology, Palaeolithic archaeology and _ industrial archaeology). The survey considers the importance and potential of the resource in and around the extraction sites.

Se SE Ee Re ee ee gee Photo courtesy of the Ancient History of Britain Project / Natural History Museum

re-evaluation of an important site; argued to contain interstratified assemblages from the Clactonian, Acheulian and Levalloisian industrial succession. At Aveley, to the north of Greenlands, exposed sections were examined. The analysis of the results supported the attribution of the sequence to MIS 7, but also suggested that within this there may be more than one temperate phase, each represented by separate vertebrate assemblages. Excavation on the A13 at Aveley recovered the first evidence for the presence of the jungle cat (Felis chaus) in Britain as well as other Pleistocene fauna. Also in Essex, relatively undisturbed Levallois knapping debris has been recorded at Lion Pit, West Thurrock, from the basal gravel of the Tapling/ A synthesis of the Pleistocene history and early human occupation of the River Thames valley has been published (Bridgland 1998). Excavations of the Middle Pleistocene fluvial deposits of the Corbets Tey Formation at Purfleet, Essex provided evidence for a previously poorly recognized interglacial, thought to correlate with MIS 9. The deposition evidence suggests that this formation was part of the Thames, rather than a minor tributary as previously suggested. Rescue excavations at Greenlands aka Dolphin) Pit, Purfleet, Essex, suggest an intermediate age for the Greenlands shell bed between the MIS 11 and MIS 7 interglacials and an MIS 9 date for this interglacial proposed. The work at Greenlands resulted in the

The long mortuary enclosure at Feering, Essex. Copyright Essex County Council

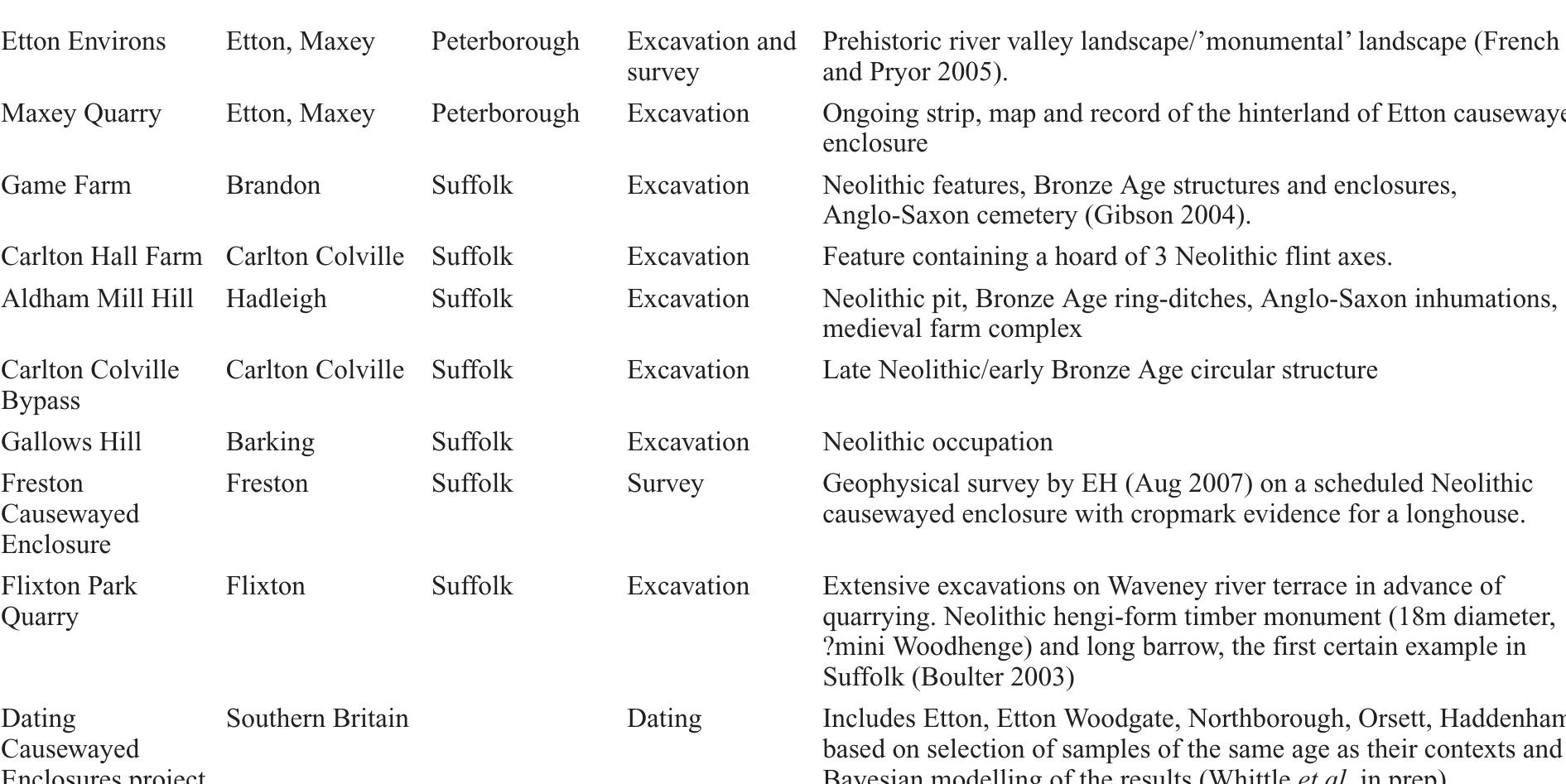

Cropmarks of the barrow cemetery at Langham in the Stour Valley. Copyright Essex County Council As well as a number of Mesolithic and Neolithic occupation sites (see Garrow 2006 for summaries), a full picture of Bronze Age river valley/floodplain land-use in Cambridgeshire is emerging from the Barleycroft Farm and Over Quarry fieldwork, which extended across both banks of the lower reaches of the River Great Ouse. Not only has this included the excavation of field systems, open and enclosed settlements, but also of ring-ditches (one with a cemetery of 35 cremations) and barrows (Evans and Knight 2000 and 2001; see also Bradley 2007, fig. 4.7 and Yates 2007, 95-6, fig. 10.6). Included in the barrow groups are two new pond barrows, previously unknown from the area, in association with unditched, turf-built barrows containing multiple cremations in A synthesis of cropmark data from the Stour valley has provided insights into the nature and development of the remarkable cropmark landscapes of monument complexes and fields which exist there (Brown ef al. 2002). The results of the Essex cropmark enclosures project have also been published (Brown and Germany 2002), establishing the importance of testing the interpretations of cropmark evidence. The excavation of the barrow cemetery at Fen Farm has once more demonstrated the proliferation of this monument type on the Tendring peninsula in Essex.

Seahenge, on the north coast of Norfolk Copyright Norfolk County Council

The Haddenham (Evans and Hodder 2006b), Colne Fen, Earith project has seen the excavation of eight separate middle-later Iron Age enclosures (Evans et al. forthcoming). Aside from further detailing the fen-edge economics of these communities, these investigations have provided crucial insights concerning what seems to be the ‘arrival’ of late Iron Age wheel made pottery-using groups into the area in the late Ist century BC; their organically ‘planned’ enclosure complexes superseding and markedly contrasting with the area’s earlier, middle Iron Age square compound ‘communities’ (with Scored Ware pottery). The obsolescence of the earlier Iron Age storage pit (e.g. at Wandlebury ringwork) in the later phases of this

continued on facing page

At Lodge Farm, St Osyth, Essex, rectilinear enclosures and trackways were laid out across the site in the middle Iron Age, followed by an extensive settlement (Germany 2007). Notable features of the Essex coastline are the Red Hills and salterns along the former boundary between salt-marsh and dry land, a middle Iron Age example has been investigated at Tollesbury Creek, Essex (Germany 2004). This date is unusual when compared with the earlier studies (e.g. Fawn et al. 1990) and raises the question of how many of the other known Red Hills that have been mapped but not investigated in detail are also of this date? thought to represent the remains of either barrows or mortuary enclosures (Albone et al. 2007a; 2007b; 2008). These monuments generally occur as small groups or as isolated monuments. Within Norfolk, similarly sized small square ditched enclosures, possibly containing cremation deposits, have been excavated at Harford Farm and Trowse, both to the south of Norwich. These were interpreted as late Iron Age/Roman funerary monuments associated with a cremation tradition (Ashwin and Bates 2000). A possible example of an Iron Age square barrow or mortuary enclosure was excavated in advance of aggregate extraction at Salter’s Lane, Longham, and was thought to be of probable middle to late Iron Age date (Ashwin and Flitcroft 1999, 253). Small ring-ditches of Iron Age date, also thought to represent funerary monuments or mortuary enclosures, have been excavated at both Shropham and Watlington.

continued overleaf

Lakenheath, Braintree and Great Chesterford, and at Caistor St Edmund where the geophysical anomalies appear to pre-date the Roman street pattern. conversion of late Iron Age ritual sites into the Roman period, at Elms Farm (Atkinson ef a/. in prep.) and Great Chesterford in Essex (Medlycott forthcoming) and Ashwell in Hertfordshire. On the Airport Catering Site, Stansted Airport, the late Iron Age settlement and shrine were abandoned at the beginning of the Roman period, but offerings in the form of brooches were still deposited during the early Roman period. The rich burials in the Colchester Stanway funerary enclosures, which include the ‘druid’ burial, are mostly of Conquest period, but the rite is emphatically native (Crummy et al. 2007).

Slaves and cattle being paraded through an Iron Age village in Essex after a raid by warriors. Reconstruction drawing by Peter Froste, copyright Peter Froste

compounds dating to the mid Ist century AD which respected a major north-west/south-east oriented road- line; a later Ist-century cemetery included three cremations and sixteen inhumations. Also dating to this phase, eleven kilns were excavated, dispersed throughout the margins of the system and proving to be very similar to those at Greenhouse Farm, Fen Ditton. community and various traders), this was clearly a major regional centre. The plans of more than sixty substantia timber structures were recovered, including an ‘official range, warehousing and a large granary building along the eastern side of the road bisecting the site. The settlemen was enclosed by a polygonal-plan ditch and bank system during the 3rd century; this evidently survived as an earthwork and was ‘visited’ during the later centuries of the first millennium, as a series of Anglo-Scandinavian worked bone items were found here. Otherwise, yielding more than 70,000 pottery sherds, some 45,000 anima bones and more than 2,000 coins, this is a site of grea significance for the region’s Roman studies (see also Evans and Regan in Malim 2005 for further summary). p)

Excavation in progress at Camp Ground, Cambridgeshire. Copyright Cambridge Archaeological Unit

Water Newton (Durobrivae) was one of the region’s largest Roman towns and a major industrial centre (Fincham 2004). Its traditional identification as a ‘small town’ is questionable given its total extent and its apparent central role in the sub-region. It is associated with high

the same site also had evidence for possible Roman flint-working, producing flakes for a threshing machine. Metal-detection has recovered metal moulds relating to the production of early Roman brooches at Old Buckenham, Felmingham and Brancaster. A number of sites, also in Norfolk, have produced evidence in the form of ingots or blanks for the manufacture of coins. The roadside settlement at Long Stratton, Norfolk had evidence for both bone- and metal-working. pothole repairs have been investigated at Snettisham (Strickland Avenue) and Buxton with Lammas in Norfolk. Excavations were undertaken across two Romano- British canals and the Fen Causeway in Norfolk, as part of the Fenland Management project. Evidence for the construction of the canals and roads, their maintenance and their final phases of abandonment, was revealed at each site. These routeways provided a crucial link from central Britain, via East Anglia, to the North Sea and beyond, and the associated environmental data greatly increases our understanding of the environment and its effects on these communication routes. Excavation of the junction of the Car Dyke and River Cam at Waterbeach revealed that it had a mid-2nd- -century Antonine/ Hadrianic construction date, with abandonment by the 4th century. Horningsea-style pottery kilns and a riverside warehouse stood on the Car Dyke canal bank at this junction. Both the warehouse and the canal contained very arge pottery assemblages, in addition important environmental data was recovered, suggesting military- sized grain storage facilities. At the small town of Scole on the Suffolk/Norfolk border there is evidence for the full industrial range, including the working of metals, bone, antler, leather and wood (part-finished wooden bowls), carpentry, malting, milling and tanning.

the transition of religious practice on existing sacred sites, as well as providing further evidence for sacrifices and the nature of participation in the rites. A major late Iron Age/ Roman temple has been discovered at Ashwell in Hertfordshire, including a hoard of temple treasure and Bronze Age metalwork that was collected in the Roman period and subsequently re-deposited. The collection of ancient items, most notably of Bronze Age metalwork, as at Harlow Temple and Lexden tumulus, and a group of Palaeolithic hand-axes at Ivy Chimneys, all in Essex, is becoming an increasingly recognised phenomenon in the Roman period. Similarly reuse of earlier sites in the Iron Age and Roman period, at Harlow for instance in the Iron Age a large roundhouse, which seems to have been the focus of coin distribution, was built close to a Bronze Age cemetery and ?pond barrow; the Roman temple was constructed immediately adjacent to these sites. At Ardleigh a Bronze Age barrow was reused as cemetery in the Roman period (see above). Structured deposition is now appreciated to be a widespread phenomenon (there Roman management of the shallow shifting courses of the River Welland through a series of meandering-ditches has been revealed at Maxey Quarry. This was accomp- anied by the creation of a ditch-defined field system on the former floodplain.

Horse burial at Marsh Leys Farmstead, Bedfordshire. Religious practice or natural death? Llanrwaterht+ AlhtgAan AvnahnnnlrAam

A number of Roman rural cemeteries have been excavated; examples include those at Stansted Airport and A small group of inhumations on the top of Blood Hill at Bramford in Suffolk included a woman and two children who had died in violent circumstances but were buried with full grave goods in the 4th century. At RAF Lakenheath, scattered inhumations have been found in ditches and possibly under floors. A review of Roman burials in Norfolk has been published (Gurney 1998), which draws together what little is known (only 245 Roman burials are recorded).

Roman/Anglo-Saxon transition A number of sites have provided evidence for the Roman/ Anglo-Saxon transition period: RAF Lakenheath and Handford Road in Suffolk, the Oakley Road and Ivel Farm settlements in Bedfordshire, Brandon Road in Norfolk and Maltings Lane in Essex; 5th-century activity has also been suggested at the Little Oakley villa in Essex (Barford 2002, 197-8). At Great Holts, Essex there is evidence for Saxon robbing of the ruins of the Roman ‘villa’. The late Roman tile building at Horsey Hill, Cambridgeshire, was re-used in the Saxon period. The site of the Romano-British temple and mausoleum at Gallows Hill, Swaffham Prior in Cambridgeshire, was re-used as a pagan Saxon burial ground in the 5th and 6th centuries. At Kilverstone in Norfolk, the early Saxon settlement on the Norwich Road is possibly deliberately re-occupying the Roman settlement, with sunken-featured buildings located within existing hollows. At Venta Icenorum there is geophysical evidence for an enclosure possibly post-dating the Roman street- grid. However there are also sites where there is no evidence for any continuity of settlement, as at Melford Meadows in Norfolk. Early Roman military

Faith Vardy/Museum of. London Archaeology The emergence of a monetary economy, trading networks and the Christian Church as a major landowner is another major research theme. Earlier research concentrated on the emporia such as Ipswich, but more recently metal-detector (PAS) data and developer-funded

continued overleaf At Stotfold in Bedfordshire an extensive Saxo- Norman settlement has been identified to the south of the A number of other rural Saxon settlements have been excavated in the region. At Brandon Road Thetford, Norfolk and at Maltings Lane, Essex there is evidence for early Saxon occupation following the Roman occupation of the site. At Takeley on the A120 in Essex, a timber Recent large-scale excavations in Norwich have revealed considerable evidence for late Saxon buildings and related activities. At the Greyfriars site, a range o manufacturing activities including antler-working and metallurgical debris was found, as well as possible evidence for minting (Emery 2007). The excavations at Castle Mall have helped shed light on the origins and development of the town, as well as enabling a revision o late Saxon and early medieval pottery dating (Shepherd Popescu 2009). Excavation on the Norwich Cathedra Refectory site has confirmed the long-held supposition that this area of Norwich was populated during the late Saxon period. Timber buildings, rubbish pits and a rutted trackway which developed into a metalled road were recorded (Wallis 2006).

Saxon hall was excavated, this had no finds but was radiocarbon-dated to the 9th century (Timby ef al. 2007). In Bedfordshire, a Saxon settlement has been identified at Marston Moretaine, close to the core of the medieval

Also in Norfolk, excavation at The Old Bell adjacent to the parish church in Marham has revealed a possible late Anglo-Saxon manorial centre, comprising a number of SFB set within a ditched enclosure. This site had its origins in the middle Saxon period and remained in use until the 13/14th-century. The Norfolk ALSF NMP project has recently identified a probable late Anglo-Saxon manorial Welcome publications include the 1983-92 excavations at Sutton Hoo royal cemetery (Carver 2005), the Anglo- Saxon cemetery at Barrington in Cambridgeshire (Malim

A corpus of Anglo-Saxon material from Norfolk has been assembled from excavated material, field-walking metal-detecting finds (West forthcoming) and this and will complement the corpus already published for Suffolk (West 1998). Analysis has been undertaken of midd late Anglo-Saxon dress accessories, assessing the im e to pact of Scandinavian settlers upon the historic environment in East Anglia. Corpuses have also been published on A series of fifty-seven pits associated with mid-late Anglo-Saxon charcoal production has also been recorded Recent survey and excavation in advance of limestone extraction at Wittering near Peterborough has revealed a very rare example of an e arly-middle Anglo-Saxon iron-working landscape comprising slag scatters, furnace bases, tapping pits, charcoal 2003; Abrams and Wilson working on the fringes of Peterborough has long been sites had been assigned an Though not accompanied burners, etc (Abrams 2002; 2003). Evidence of iron- Rockingham Forest near known, but until now these exclusively Roman date. by artefacts, a series of radiocarbon dates has estab investigated examples are in ished that all the recently fact Anglo-Saxon. Further work on the extent and importance of this industry in post- Roman times is now necessary.

Early Saxon village at Brandon Road, Thetford. Reconstruction drawing by Jon Cane, copyright OA East

late Saxon and medieval origins and subsequent development, see for instance Cherry Hinton (Cessford and Dickens 2005b). those at Stansted Airport (Havis and Brooks 2004; Cooke et al. 2008) have identified patterns of settlement and fields. Fieldwork at Papworth Everard, Cambridgeshire, has revealed information about development of the late Saxon and medieval agricultural landscape, including elements such as ridge-and-furrow, enclosures, church land boundaries. Rapid Coastal Surveys in Norfolk, Suffolk and Essex have recorded many medieval and post-medieval features relating to the management and exploitation of the medieval coast, including sea-walls, grazing-marshes and salterns. In Essex a number of desk-top and walkover surveys have been undertaken on tracts of former grazing marsh along the coast. On a smaller scale, a watching- brief at Vange Marsh North recovered medieval pot from relict channels, dating coastal/estuarine activity in the area.

In Suffolk, survey and palaeoenvironmental fieldwork at Framlingham Mere established that the mere had its origins as a prehistoric pool that was subsequently adapted to serve as a water ‘mirror’ for the medieval castle. A geophysical survey was undertaken within Clare Castle. Earthwork and geophysical surveys have been undertaken at Orford Castle, demonstrating that this important 12th- The Broad Street excavations in Ely have made an important contribution to the study of the medieval urban development of Ely, revealing a deeply stratified continuous building sequence dating from the 12th

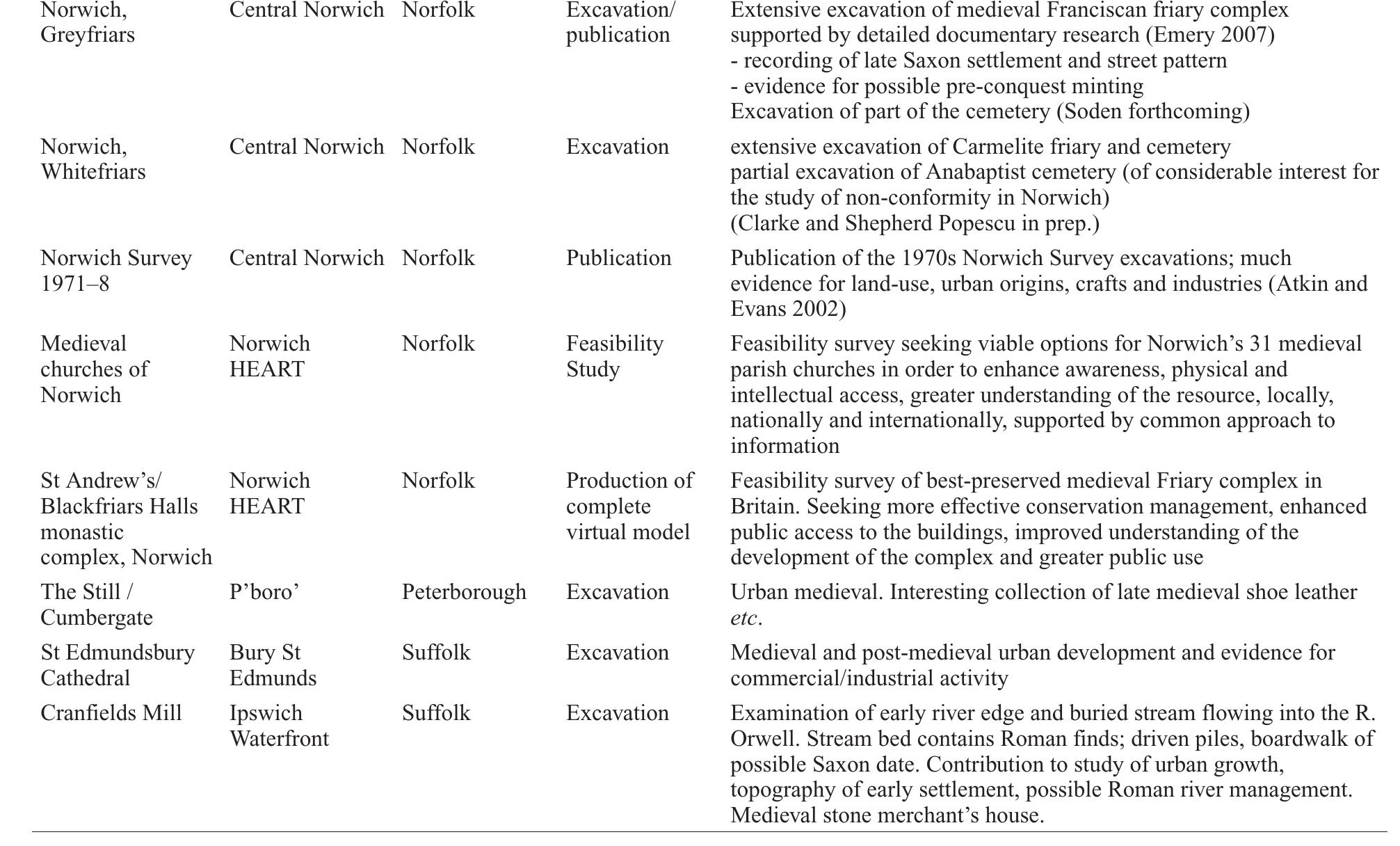

A considerable body of work has been undertaken in Norwich since 2000. Publication of Norwich Survey excavations in the 1970s is particularly welcome (Atkin and Evans 2002). This report uses the evidence of a comprehensive campaign of excavations, building survey and documentary research to explore land use through different sectors of the city, and how this changed during the medieval and early post-medieval periods. Many of the sites produced evidence for crafts and industries, including bell-casting, quarrying, tanning or horn- working, and a medieval dyeworks. The Castle Mall excavations have advanced urban castle studies and shed light on the processes of urban development and urban living, They have also advanced cemetery studies, including the identification of leprosy victims; and produced extensive palaeoenvironmental and artefactual evidence including a probable pottery production centre beneath the castle mound and a huge mid to late 15th- century assemblage from a castle well (Shepherd Popescu 2009). Extensive excavations were undertaken on the Greyfriars Franciscan friary, supported by detailed documentary research (Emery 2007) and further work took place in the friary cemetery (Soden forthcoming). At Excavations at Market Mews/Little Church Street, Wisbech have revealed an impressive sequence of deeply stratified medieval to early post-medieval deposits, comprising at least thirteen building phases with intervening episodic flooding (Hinman and Popescu forthcoming). Whilst the alternate sequence of occupation and flooding is broadly comparable to deposits in other regional port towns, it is almost without parallel in terms of its completeness, depth and state of preservation.

changes to the construction design, however, is a risky strategy for the archaeology. Emerging evidence suggests that organic remains in particular often do not survive as expected post-development. The investigation of medieval reclamation and settlement at Newlands, King’s Lynn also included environmental monitoring of the site pre- and _ post-development (Brown and _ Hardy forthcoming). Norwich Whitefriars there were extensive excavations of the Carmelite friary and cemetery (Clarke and Shepherd Popescu in prep.). A feasibility survey of the best- preserved medieval friary complex in Britain — St Andrews/Blackfriars Hall, Norwich — _ has been undertaken to enhance conservation management and public access, and it includes a complete virtual model. Another feasibility survey was undertaken for Norwich’s 31 medieval parish churches, seeking viable options for enhancing awareness, providing access and understanding the resource. The development of Norwich Cathedral Close has been examined in depth (Gilchrist 2005), comparisons with other cathedral closes enable a broader understanding of the development of the English cathedral landscape over six centuries. King (2006) has compiled an overview of the archaeological evidence for urban households in Norwich, and excavations at Dragon Hall, a medieval merchant’s house, have been published (Shelley 2005).

Thorney community excavations, Cambridgeshire. Copyright OA East, photographer Richard Mortimer A number of rural medieval institutions have been investigated. These include the excavation of a A synthetic assessment h excavated medieval rural sites in as been prepared for Essex. These included a royal moated hunting-lodge, 12th- to 14th-century farms and farmsteads, single-roomed cottages and two windmills (Medlycott 2006). Large-scale excavations have taken place as part of the development of Stansted Airport, recording a moated si e, farmsteads, cottages, hunting-lodge, a windmill and field systems (Havis and Brooks 2004; Cooke et al. 2008). of the Channel Tunnel Rail link things, the manor of Stone H originated in the 11th century. complex at Southchurch Hal Excavations in advance revealed, amongst other all in Thurrock which The moated manorial , Southend, has been published (Brown 2007). Churches, dwellings and agricultural buildings have been recorded, together with more specialised structures suc h as detached kitchens, both as part of the development control process and as part of thematic surveys. The site of the medieval manor and 17th-century mansion house at Tyttenhanger, Hertfordshire, was excavated. This revealed an early medieval field system, two corn-driers, a late medieval courtyard flanked by gatehouses or towers, a second late medieval enclosure with stables and tile kilns, early post-medieval formal garden and avenues and ranges of contemporary outbuildings (Hunn 2004). In Norfolk the fortified manor house of Baconsthorpe Castle has been published, the report comprising the excavations, earthworks and buildings survey and documentary analysis (Dallas and Sherlock 2002). documented late medieval hospital and its graveyard on the Baldock bypass in Hertfordshire. At Chevington Hall, Suffolk, the country residence of the medieval abbots of Bury St Edmunds was partially excavated, and a medieval ringwork was investigated at Court Knoll, by geophysical survey and fieldwalking. The site of the medieval church at Creeting St Olave was examined by geophysical survey and excavation (MacBeth 2003). In Essex, a programme of excavation has been undertaken at Beeleigh Abbey, to the north-west of Maldon, revealing a house and smithy adjacent to the abbey precinct, a monastic kitchen and brick-clamp. Lordship Lane, Cottenham revealed continuity of settlement from the middle Saxon through to the early medieval period, with dynamic interaction between manor and village, including the razing of part of the village and its incorporation into the manor demesne (Mortimer 2000).

continued on facing page

Industry A medieval fishery, comprising two fishing platforms and a substantial assemblage of fish remains, pottery and lead weights, was excavated at Whittlesea Mere, Cambridge (Lucas 1999). There is documentary evidence for the abbeys of Peterborough, Thorney and Ramsey having the right to fish on the Mere. The Castle Mall site in Norwich (Shepherd Popescu 2009) revealed probable Thetford-type pottery production as well as evidence for numerous other crafts/industries, including a huge | 5th-century assemblage from infills ofa castle well which comprised a wide range of waste from artisans working around the Castle Fee. A comparative study of the Anglo-Saxon to 17th-century pottery from Colchester, focussing on local wares, has been published (Cotter 2000). A newly recognised pottery type, Ely Ware, dating to the mid 12th to 15th centuries, has been identified and published (Spoerry 2008). The Norfolk Coast and Broads NMP projects recorded large numbers of saltern mounds within The Wash and, to a lesser extent, around Breydon Water and the former Great Estuary (Albone eft al. 2007a). This has made a significant contribution to the study of this important medieval industry, and represents the first comprehensive identification and analysis of such sites within the county. The recognition of evidence for the possible late Saxon origins of some of the saltern mounds provides further evidence for the early development of this form of salt-making (i.e. sand washing). In Cambridgeshire, the Bourn medieval ironworking project has investigated a unique group of settlements attached to larger manorial units which were apparently focussed on small-scale iron-smelting and smithing. At Frogs Hall, Essex, an example of a rural pottery site has been examined, comprising nine kilns. Late medieval tile kilns were recorded at Tyttenhanger in Hertfordshire Hunn 2004). Excavations at the Grand Arcade in Cambridge have revealed evidence for bone- and horn-working. The mapping of features relating to the medieval and post-medieval peat extraction industry that created the orfolk Broads has added significantly to the large body of existing data concerning this subject. The use of aeria photographs has greatly increased the extent of the known areas of extraction, particularly those of the medieva period. The analysis of the medieval to post-medieva extraction evidence in relation to Historic Landscape Characterisation (HLC) mapping proved particularly fruitful. A number of medieval windmill sites in Essex have been published: a windmill and farmstead complex at Bulls Lodge Quarry, Boreham (Clarke 2003), a windmill and farmstead at Stansted Airport (Cooke et al. 2008), and an isolated windmill on the A120 trunk-road (Timby eg al. 2007). Two further windmills were identified during the cropmark enclosures project (Brown and Germany 2002).

In Hertfordshire a programme of dendrochronology dating is underway, six medieval timber-framed buildings (mostly barns) have been dated, some proving earlier than expected. Progress has been made with reconstructing tree-ring sequences in other areas. Since the 1980s, the Essex Tree-Ring Dating project has encouraged and co-ordinated dendrochronology in the county, including a programme on small aisled halls (Stenning 2003). Essex tree-ring dates are published in Essex Archaeology and History, whilst a list of all dates obtained so far is available on the Essex County Council website. Dendro-dating of buildings is also underway in Suffolk. A settlement- targeted dating programme has been successfully carried out at New Buckenham in Norfolk (Longcroft 2005). At Peterborough Cathedral, dendrochronology dates the The faunal assemblage from the Castle Mall excavations in Norwich is published (Albarella ef al. 2009). An interesting group of butchered and skinned cats from Cambridge has been published (Luff and Garcia 1995).

continued on facing page

There have been a number of important excavations and publications since 2000. In Cambridgeshire a riverside site in Broad Street, Ely, revealed a deeply stratified continuous building sequence dating from the

appreciation of the deposit quality and research potential of the city. important group of burials from an Anabaptist cemetery, which is of considerable interest for the study of non-conformity in the region (Clarke and Shepherd Popescu in prep.). The Stevenage Historic Characterisation project covers the whole borough, it has defined a range of character types for urban and suburban areas which are based on Lancashire models that have been adapted for use in Hertfordshire, acknowledging the pioneering 20th- century housing types from the Garden City movement onwards. In Bury St Edmunds, excavations have included medieval and post-medieval urban development around the vicinity of St Edmundsbury Cathedral and a rare opportunity to excavate within the Regency Theatre Royal, the oldest surviving purpose-built theatre in Britain.

Nitro-glycerine mixing-house at Waltham Abbey gunpowder factory. Copyright Essex County Council Ongoing survey of post-medieval flint mines in north- west Suffolk and south-west Norfolk includes the examination of aerial photographs, which demonstrates three types of mining in the late 18th to 20th centuries. Aspects of the chalk extraction and lime production industry have also been highlighted by excavations in Norwich and Bury St Edmunds. Parks and gardens

1750-1900, local railways, military airfields, industrial housing and watermills. In addition, recording and excavation of industrial sites and historic buildings has become fully integrated into development control practice in Essex. Notable surveys include the extensive recording of the internationally important Waltham Abbey Gunpowder Factory, a Tudor brick clamp at Beeleigh Abbey, a 1 9th-century brick-clamp at Wendens Ambo that was subsequently converted into a cottage, and the excavation of 19th-century brickworks at Sible Hedingham and Chelmsford.

including individual air raid shelters in private gardens, could be identified. A synthesis of the aerial photographic evidence for the coastal defences of Suffolk has been published (Hegarty and Newsome 2007). together with the uniform and comprehensive nature of the survey, has added enormously to our knowledge and understanding of the subject, in particular (due to the date of the photographs) the defences of World War Two. Recorded sites include anti-invasion defences (even those which were temporary), coastal batteries, anti-aircraft defences (batteries, searchlights, barrage balloons, bombing decoys), radar stations, airfields, training sites, camps (including PoW camps) and civil defences. The mapping of World War Two defensive sites within urban areas such as Great Yarmouth, where they were mapped in great detail from low-level photographs, has been extremely productive; many of the civil defences, ~ Excavations have included the discovery of the Civil War ditch at Cambridge Castle (Cessford 2008). Assessment of progress on research topics proposed in 2000 The Research Agenda and Strategy (Gilman ef al. 2000; Brown ef al. 2000) highlighted a number of research

Norwich Castle c.1700, showing the infilling of the Castle ditches. Reconstruction drawing by Nick Arber, copyright Norfolk Museums and Archaeology Service

Although the NMR documents hundreds of wrecks and hulks off the East Anglian coastline, only one, off

Mesolithic handaxes from the North Sea. Photo courtesy of the National Museum of Antiquities (RMO), Leiden (The Netherlands). Photographer Peter-Jan Bomhof

Anglo-Saxon fish-trap visible in the river Stour at Holbrook Copyright Suffolk County Council Archaeological Service

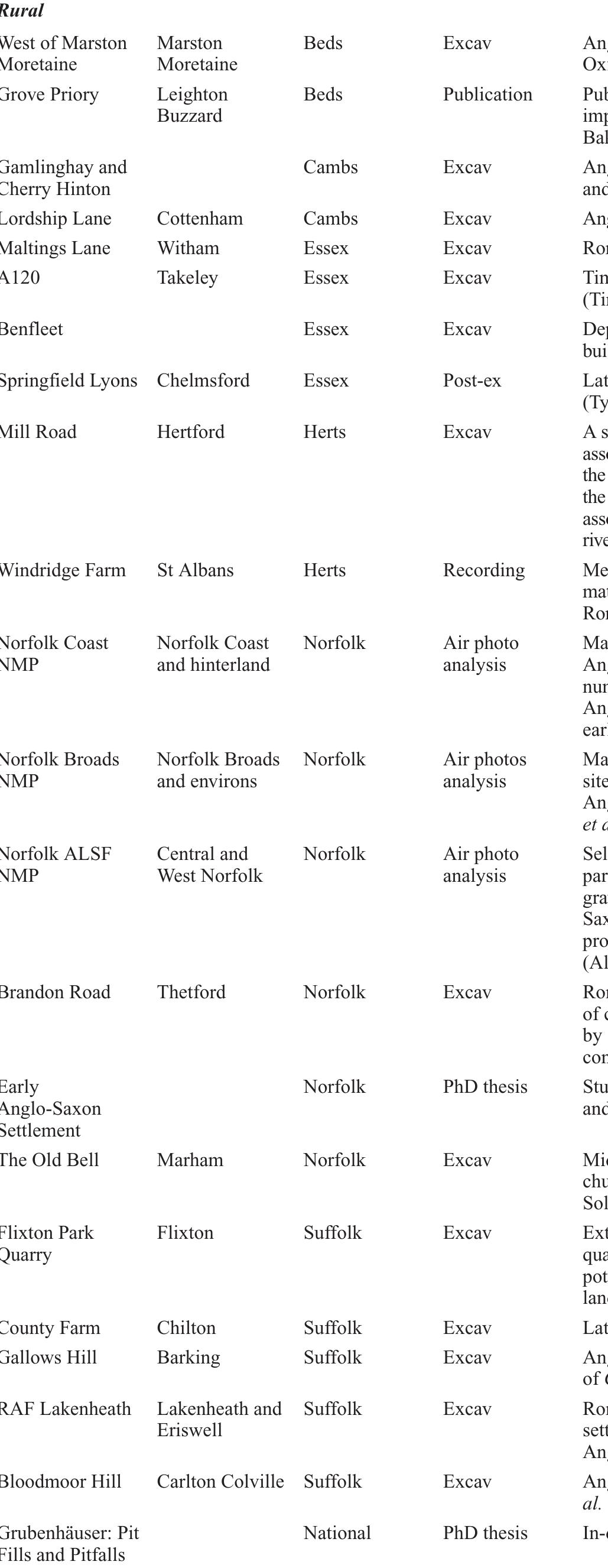

“Bronze Age and medieval sites at Springfield, Chelmsford: excavations near the Al2 Boreham Interchange, 1993’, Essex Archaeol. Hist. 30, 1-43