About "Alice's Adventures in Wonderland", the book - Alice-in-Wonderland.net (original) (raw)

Quick facts

- Full title: Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

- Author: Lewis Carroll (pen name of Charles Lutwidge Dodgson)

- Illustrator: Sir John Tenniel

- Original title: Alice’s Adventures Under Ground

- Printing date of the recalled first edition: 4 July 1865

- Publishing date of the approved first edition: 18 November 1865 (but dated 1866)

- Publisher: Macmillan

- Place of publication: Oxford

- Translated: in more than 174 languages

How the story began

Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (the real name of Lewis Carroll, the author) often told stories to his child-friends, amongst which Alice and her sisters. Sometimes these stories, which he made up on the spot, were told when they were visiting him in his rooms, sometimes on other occasions, like river picknicks.

The first version of the story of “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland” arose at 4 July 1862. Charles Dodgson, his friend reverend Canon Duckworth, and the sisters Alice, Lorina and Edith Liddell were on one of their boat trips on the river Isis (the local name for the stretch of the Thames that flows through Oxford) from Oxford to Godstow. Alice grew restless and begged Dodgson for a story “with lots of nonsense in it”. Dodgson began, and, as usual, invented the story while he was telling it. Much of the story was based on a picnic a couple of weeks earlier when they had been caught in the rain.

Several times Dodgson tried to break off the story (‘all until next time’), but the children were not to be put off. They didn’t return at the Deanery until late in the evening.

This is how Duckworth described the trip afterwards:

“I rowed stroke and he rowed bow (the three little girls sat in the stern) … and the story was actually composed over my shoulder for the benefit of Alice Liddell, who was acting as ‘cox’ of our gig … I remember turning round and saying, ‘Dodgson, is this an extempore romance of yours?’ And he replied, ‘Yes, I’m inventing it as we go along.’ “

On two other boat trips, Dodgson continued the series of ‘Alice stories’. At that point, they were more a collection of individual tales than one integral story.

Read how Dodgson described the trip and the invention of the story, in his article ‘Alice on the Stage‘.

It is not known how long exactly Dodgson took to finish his tale. More than a month later, on 6 August 1862, he records in his diary that he took the girls on another boat trip and “had to go on with my interminable fairy-tale of ‘Alice’s Adventures.'”.

In an article in the New York Times of April 4th 1928, Alice Liddell recalled:

“The begining of Alice was told to me one summer afternoon ,when the sun was so hot we landed in the meadows down the river, deserting the boat to take refuge in the only bit of shade to be found, which was under a newly made hayrick. Here from all three of us, my sisters and myself, came the old petition, ‘Tell us a story’ and Mr. Dodgson began it. Sometimes to tease us, Mr. Dodgson would stop and say suddenly, ‘That’s all till next time.’ ‘Oh,’ we would cry, ‘it’s not bedtime already!’ and he would go on. Another time the story would begin in the boat and Mr. Dodgson would pretend to fall asleep in the middle, to our great dismay.”

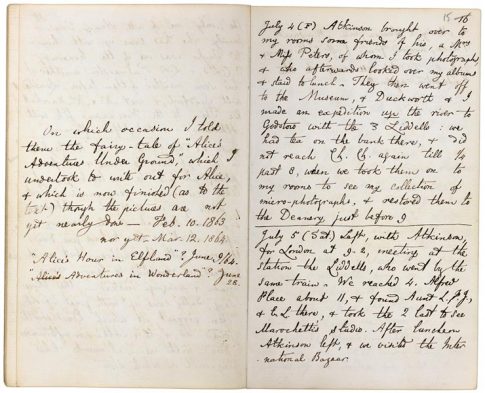

Reproduction of the manuscript “Alice’s Adventures Under Ground”

Normally, after a story had been told, it vanished in air as quickly as Dodgson had invented them. However, Alice must have liked these particular stories very much, because she asked Dodgson to write the story down for her. Initially, he was hesitant, but eventually he gave in to Alice’s pleads. Dodgson stayed up late that night to jot down the main events, and sketched an initial outline of the story the day after, during a train journey.

He started the writing of the full text on 13 November 1862, and completed it on 10 February 1863 (Goodacre, “The works of”). Dodgson expanded the story somewhat when writing out his oral tales. In the article ‘Alice on the Stage‘ he tells us: “In writing it out, I added many fresh ideas, which seemed to grow of themselves upon the original stock”.

As an adult (in 1932), Alice commented about this process (Cohen 84):

“[…] I think many of my earlier adventures must be irretrievably lost to posterity, because Mr Dodgson told us many, many stories before the famous trip up the river to Godstow. No doubt he added some of the earlier adventures to make up the difference between Alice in Wonderland and Alice’s Adventures Underground, which latter was nearly all told on one afternoon. Much of Through the Looking-Glass [TTLG] is made up of them too, particularly the ones to do with chessmen, which are dated by the period when we were excitedly learning chess. But even then, I am afraid that many must have perished for ever in his waste-paper basket, for he used to illustrate the meaning of his stories on any piece of paper that he had handy.”

When the story was finished, he copied it out again, more carefully and in a hand that Alice would find legible, and left spaces for pictures of his own drawings. He called this manuscript “Alice’s Adventures Under Ground“.

Before he added the drawings, he practiced first by creating several sketches. It took Dodgson a while to complete the pictures: he finally finished them on 13 September 1864, and thereby completed the manuscript.

Dodgson retained the manuscript version for reference as he expanded the book into “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland” (see below) (Goodacre, “The works of”). He finally presented the finished manuscript, a leather booklet, to Alice as a Christmas gift, on 26 November 1864.

Publishing the story

Dodgson’s friend and novelist Henry Kingsley saw the text, even before Dodgson had presented the completed manuscript to Alice, and encouraged him to publish the book. Dodgson asked advice from his other friend, George MacDonald, an author of children’s books. MacDonald took the manuscript home to read it to his children, and his six-year-old son Greville declared that he “wished there were 60,000 copies of it”, so Dodgson decided to publish it, and finance the whole project himself. Sometime early in 1863 the decision was made, but it was May 1864 before the first sections were completed.

Dodgson revised the story by cutting out the references to the previous picnic and expanded the original tale considerably; he added some chapters, altered some poems and added jokes that had occurred to him later. The first version had not included “The Caucus Race”, “Pig and Pepper” and “A Mad Tea-Party”. The Cheshire Cat had not been invented, the Ugly Duchess was called “the Marchioness of Mock Turtles”, the part of the Mock Turtle’s schooldays lacked and the greater part of the Trial scenes was written later. The Mouse Tale was different.

The story also got a new title. In a letter to a friend Dodgson explained that he feared that “Alice’s Adventures Under Ground” might appear to be a book containing ‘instruction about mines’ and therefore suggested:

“Alice among the elves / goblins” or

“Alice’s hour / doings / adventures in elf-land / wonderland”

He personally preferred “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland”, so this became the final title.

Dodgson liked to draw himself, and originally wanted to use his own illustrations for the published edition. After several of his artistic connections discouraged him from doing that, he eventually admitted that his talents lay in directions other than those of a draughtsman. Around 25th January 1864 he approached Sir John Tenniel, a cartoonist for the magazine ‘Punch’, to draw the illustrations. Dodgson provided Tenniel with detailed instructions how to draw them. Read more about the illustration process.

Dodgson was very concerned about how his book would look, and discussed the options extensively with his publisher. On 21 June 1864 he visited Macmillan, who advised him to alter the size of the page, and to choose a size similar to that of the ‘Water Babies’ by Charles Kingsley. Carroll discussed it with Tenniel, who agreed, and Carroll then agreed as well (Hancher 130).

He chose the color bright red for the cover of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. On 11 November 1864, Dodgson wrote to Macmillan:

“I have been considering the question of the colour of Alice’s Adventures, and have come to the conclusion that bright red will be the best – not the best, perhaps, artistically, but the most attractive to childish eyes. Can this colour be managed with the same smooth, bright cloth that you have in green?”

The very first edition did not have gilt edges. Dodgson wrote to Macmillan on May 24th, 1865:

“As I want it to be a _table_-book, I fancy it would look better with the edges evenly cut smooth, and no gilding”

The original first edition of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

Christ Church Library holds several interesting items, like drafts, proofs, and galleys, that show how the book developed from a manuscript to a printed book.

The book was ready on 4 July 1865, exactly 3 years after the famous boat trip. It was printed by the Clarendon Press at Oxford University Press, and bound by James Burn & Co. from London.

This first edition consisted of 2,000 prints, but because of Tenniel’s dissatisfaction with the printing quality of the pictures, ink bleed on the pages, widowed lines, and the use of mixed fonts, all 50 (presentation) copies that had been bound by that time, were recalled within a month. All but about 23 copies were successfully fetched back and donated to children’s hospitals and the like. Only 22 copies are known to have survived until now. (For a detailed description of all known presentation copies, see Selwyn Goodacre’s “Census of copies of the suppressed 1865 Alice“.)

In a second attempt, again 2,000 copies were produced, using a new printer (Richard Clay of Bungay, in stead of Oxford University Press) and paper of better quality (Goodacre, “Census of copies”). This new ‘first edition’ was published on 18 November 1865 (but dated 1866) – although often the date of 26 November is mentioned (Lovett 35). Copies mainly have light blue end papers, or sometimes dark green end papers (Goodacre, “The works of”). Its paper quality, as well as its typesetting, are obviously better than the original first edition. This new first edition did have gilded edges, as Macmillan advised Dodgson to adopt this. It sold for 7s 6d (Jaques and Gidders). 125 Copies were given away (Imholtz).

Initial sales of the book were good: by 30 November, 500 copies had been sold. Dodgson however was disappointed in the numbers, and expressed this is a letter to Macmillan in March 1866. Macmillan assured him that sales would pick up without the need of advertising – and they were quite right, as we know now! As of 30 June 1866, 1362 copies had been sold (Imholtz).

The whole publication was financed by Dodgson himself: he paid for the paper, the illustrations, the engraving of the illustrations, the binding, and more. Macmillan published it under commission and received 10% for advertising and distribution (O’Connor 5).

Dodgson kept scrutinizing all editions of his tale, complaining often to Macmillan about the quality of the printing, pictures, and typesetting. It was very obvious that he was more concerned about the look of his book than of the profit he was making. In his letters to Macmillan he wrote:

“I have now made up my mind that, whatever be the commercial consequences, we must have no more artistic ‘fiascos’.”

and

“So long as it is really handsome, its paying or not is a matter of minor importance.”

Dodgson was not only very particular about the printing of his book, but also kept a tight reign on how Macmillan was promoting the volume, and wanted to be kept informed about how it was selling. He also tried to influence its pricing several times, and thought about making it available in different formats, like a cheap edition for middle class children.

Additional editions

As the book was an immediate success, a second edition was printed soon, consisting of two print runs of 2,000 each in September 1866. It was published in November 1866. By the end of 1866, 5,000 copies had already been sold. The third edition (2,000 copies) therefore appeared in 1867, as did the fourth (2,500 copies). The fifth appeared in 1868 (Jaques and Gidders).

Since the second edition, issues of the Macmillan books have the date and number of the ‘thousand’ on the title page, as was a binding convention, up to the 98th thousand in 1932. This number indicates the number of issued books in thousands. However, there appear to be some anomalies in this numbering, perhaps by fault of the printer, and we cannot always be sure that the thousand indicator on the title page corresponds with the real print number of the copy. With the help of Selwyn Goodacre, an article of Clare Imholtz (Imholtz) and the checklist by Jon Lindseth (Lindseth and Hirshon), I was able to compile the following overview of all editions and ‘thousands’ until Lewis Carroll’s death:

1st edition (the recalled edition):

- not numbered, but would count as the 1st and 2nd thousand

2nd edition (the ‘official’ 1st edition):

- not numbered, but as the first 2000 copies had been recalled, these would count as the 3rd and 4th thousand (printed 1865, dated 1866) (1 print run, although some have slate-blue endpapers and others have black ones, and the zero in the page number on page 30 is missing in some copies)

3rd edition:

- 5th, 6th, and 7th thousand (printed August-November 1866, dated 1867)

4th edition:

- 8th, 9th, and 10th thousand (the 10th being a batch of only 500 copies instead of 1000 copies) (November 1867)

5th edition:

- 10th (second batch of 500 copies), 11th, 12th, and 13th thousand (February 1868)

6th edition: (first electrotype version):

- 12th and 13th thousand (October 1868, dated 1869) (5th edition re-done in electrotype – but probably accidentally the 4th edition was mainly used instead, because the text differs from that of the 5th edition)

- 14th, 15th (probably – no copies of these have been found), and 16th thousand (printed October 1868, dated 1869)

- 17th thousand, 18th thousand, 19th thousand (no known copies of these exist) (1869)

- 20th-25th thousand (1870)

- 26-28th thousand (1871)

- 29th and 30th thousand (October 1871, dated 1872)

- 31st thousand (1872)

- 32nd, 33rd, and 34th thousand (March 1872):

- 35th thousand (dated both March 1872 and October 1872): some versions have a dual imprint (London / New York) and were intended for the US market

- 36th-41th thousand (1872)

- 42nd-46th thousand (1874)

- 47th thousand (1875)

- 48th thousand – no known copies of these exist (1875 or 1876)

- 49th -52nd thousand (1876)

- 53rd-55th thousand (1877)

- 56th-58th thousand (1878)

- 59th-63th thousand (1879)

- 64th thousand (1880)

- 65th and 66th thousand: no known copies

- 67th thousand (1881)

- [68th-75th thousand (1882-1885)]

- 76th thousand: no known copies of these exist

- 77th and 78th thousand (1886)

- 79th thousand (1886, but probably issued in early 1887)

- 80th thousand, 81 thousand, 82 thousand, 83 thousand (1886, but probably issued in 1887) (1 print run)

- 84th thousand (1891)

- 85th thousand (1892)

9th edition:

- 86th thousand (1897)

- […]

- 97th thousand: no known copies

- 98th thousand (1932)

- no thousand stated (1942)

The ‘People’s edition’ has the following editions and print runs:

- 1st to 10th thousand (December 1887) (1 print run)

- 11th thousand (1888)

- […]

- 23rd thousand (1891)

- […]

- 29th thousand (1892)

- […]

- 67th thousand (1897)

- […]

- 70th thousand (1898)

Imholtz mentions that about 87,000 copies of “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland” were sold in the UK in Dodgson’s lifetime, while Malcolm (30) gives an estimate of 150,000 copies. Macmillan’s last reprint was in 1942 (Goodacre, “The works of”).

Textual revisions

Even after publishing the story, Dodgson kept improving it. Every new edition showed some small changes compared to the previous one, which Dodgson called ‘errata’.

Up to 1868, the text was printed in letter press, so Dodgson was able to make corrections easily. After 1868, the pages were set in electrotype, which meant only minor corrections were possible (Goodacre, “The works of”).

Besides many minor changes in among others punctuation, typesetting, grammar and spelling, there sometimes were some more noticeable changes. For example, in the seventy-ninth thousand 6s edition, issued in December 1886, the poem “‘Tis the Voice of the Lobster” was expanded. Also the shape of the mouse’s tail poem was altered. Dodgson made about 400 changes to the 1886 edition, which is an enormous amount and must have been a lot of work.

Interestingly, when he made the final changes to his book in 1897 (Dodgson died in 1898, preventing him from making even more), many of these earlier corrections were omitted in the final version. This was probably by accident: Dodgson thought it a waste to spoil the printer’s file copies of the most recent version by marking and correcting them, and therefore worked from old copies he had received from a child-friend. These copies consisted of the 1882 edition of “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland” and the 1880 edition of “Through the Looking-Glass”, bound in a single volume, which therefore did not contain all his most recent corrections. Apparently he had forgotten about them (Jaques and Gidders 101).

His final changes were also extensive, and included changing all instances of “won’t”, “can’t” and “shan’t” to include an additional apostrophe (“wo’n’t”, “ca’n’t”, “sha’n’t”). The Dormouse was now referred to as ‘he’ in stead of ‘it’ (although not everywhere in the book).

For this 1897 edition he even asked Tenniel to revise some of the illustrations. Initially Tenniel agreed, but lated changed his mind because he was too busy with other work, and so the illustrations remained the same through all editions (Demakos 46).

As the 9th edition from 1897 (the ’86th thousand’) was Dodgson’s last revised edition, it is being seen as the definitive edition of the book. This one is commonly used by translators. Although one could argue that the ‘real’ definitive edition should be the 1886 edition combined with the changes made for the 1897 edition. Also, even after 1897 there are textual changes, made by editors. For example, in the 87th thousand (1898) the word “nevar” was ‘corrected’ to “never”.

Selwyn Goodacre has meticulously listed all changes between the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th, and 5th editions of “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland”, and also changes in “Though the Looking-Glass”. See:

- Goodacre, S. “The Textual Alterations to Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland 1865-1866″. Jabberwocky, Winter 1973 (Comparison of ‘true’ and ‘official’ 1st editions)

- Goodacre, S. “The Textual Alterations to Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland 1866-1867″. Jabberwocky, Winter/Spring 1988 (Comparison of the 5th thousand -wich is the same als the 6th and 7th thousands- to the ‘official’ first edition)

- Goodacre, S. “The Textual Alterations for the 4th Edition of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, 1867/1868″. The Carrollian, issue 22, Autumn 2008-published September 2011 (Comparison of the 8th thousand – which is the same as the 9th and 10th thousands- edition to the 3rd edition)

- Goodacre, S. “The Textual Alterations for the 5th Edition of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, 1868″. The Carrollian, issue 22, Autumn 2008-published September 2011 (Comparison of the 10th thousand edition – which is the same as that of the 11th to 13th thousands- with the 4th edition, and a comparison of the 12th and 13th thousands of the 6th edition to the 4th edition in appendix 1)

- Goodacre, S. “Lewis Carroll’s 1887 Corrections to Alice”. The Library, 28.2, 1975, p. 135 (Comparison of the 1887 1-10th thousand ‘People’s Edition’ with the 6th edition)

- Goodacre, S. “Lewis Carroll’s Alterations for the 1897 6s. Edition of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland”. (Comparison of the 1897 86th thousand edition with the 6th edition)

- Goodacre, S. “The Textual Alterations for the 1897 6s Edition of _Through the Looking-Glass_“. The Carrollian, issue 22, Autumn 2008-published September 2011

If you want to study the exact changes, you can order these issues from the Lewis Carroll Society.

Although Carroll scrutinized and revised his story over and over again until his death, he still overlooked several errors.

In most editions, Carroll made sure that the text and the illustrations complemented eachother, by carefully choosing and clearly specifying the locations of the illustrations within the text. Usually, textual references stand next to the related illustration and narrative moments in text and illustration are also visually synchronized. However, in cheaper editions Carroll was less careful about image placement and allowed the text and illustrations to drift apart. In the 9th edition from 1897 (and the 4th edition from Through the Looking-Glass, printed in the same year), the lay out was reset. This edition is a page-by-page and line-by-line replica of the original editions, including the original image placement (Hancher 174).

Other publications

Although Dodgson was very picky about the looks of his book in the UK, he was much less concerned about the quality of the books that were sold in America. Apparently he did not have a high opinion of the US book market. To limit his loss on the recalled first edition, he allowed the remaining printed but unbound copies of the recalled 1865 edition to be sold to the American firm D. Appleton & Co. in April 1866. The sheets were bound in England, the edges were gilded, and the book was published in May 1866 under the Appleton imprint with a cancel title page. These copies are generally known as ‘the Appleton Alice’ (Goodacre, “The works of”).

In 1887, Macmillan issued cheaper versions of “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland”, styled as ‘People’s Edition’ in green pictorial cloth.

In March 1885 Dodgson asked Alice’s permission to publish a facsimile of the original manuscript “Alice’s Adventures under Ground”. He wanted any profits that might arise from the book to be given to Children’s Hospitals and Convalescent Homes for Sick Children. The publication did not go very smoothly, because there were problems with the creation and delivery of the zinc-blocks, which eventually led to a lawsuit (Collingwood). The facsimile finally appeared on 22 December 1886 in an edition of 5,000 copies, published by Macmillan & Co, and bound in red cloth. Eldridge Johnson, a later owner of the manuscript, published a facsimile of the volume in 1936. A number of other facsimiles have been printed since.

Dodgson later completely rewrote the tale and called it “**The Nursery Alice**“. It was a shortened and simplified version for very small children ‘from nought to five’, without the puns and irony in the original tale. According to his diary, Dodgson first conceived the idea of a nursery version of Alice in the beginning of 1881, perhaps inspired by the Dutch translation of “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland” that had colored illustrations, as he wrote in a letter dated 12 April 1881 to Helen Feilden (Ruizenaar 41):

“Shall I send you a Dutch version of Alice with about eight of the pictures done large in colours! It would do well to show to little children. I think of trying a coloured Alice myself – a Nursery Edition. What do you think of it?”

“The Nursery ‘Alice'”was eventually published in 1889. It contained 20 of Tenniel’s illustrations enlarged and colored, and had a new cover illustration by E. Gertrude Thomson.

The original intention was to publish the book for Easter 1889. Carroll had finished the text on 20 February of that year, but the book only ‘passed for press’ on 18 April – probably because the cover illustration was delayed. In June Carroll received a copy of the printed sheets. Again, Carroll was dissatisfied with the printing quality of the illustrations, so after a prolonged negotiation with MacMillan, 4.000 copies were sold to America. That is why the actual first edition from 1889 was issued in America, and the first UK edition appeared on March 1890. (Goodacre, “Nursery Alice” 102)

Of the remaining 6.000 sheets, a portion were issued in 1891 as a “People’s Edition” and the remainder were issued in 1897 as a cheap issue. The new edition was published on March 25 1890, also in an edition of 10.000 copies (Lovett and Lovett).

The Nursery Alice was dedicated by Carroll to Marie van de Gucht, who was 15 during the time of publication. The prefatory poem is an acrostic verse; the second letters of each line spell out Marie’s name. (Jacques & Gidders 73)

Sale of the manuscript

The original manuscript of “Alice’s Adventures Under Ground” was sold for the 1st time at Sotheby’s (Lot # 319) in 1928. Alice Hargreaves (Alice Liddell), then an almost seventy-year-old widow, probably needed the money to be able to maintain her country house after her income decreased after WWI, so she approached Sotheby’s about selling the original manuscript. The tension and excitement surrounding this auction was incredible.

Inside of the manuscript “Alice’s Adventures Under Ground”, in the British Library

Dring of Quaritch’s bidding on behalf of the British Museum went up to £12,500. B.D. Maggs, representing the American dealer Gabriel Wells, dropped out at £15,200. Dr. A.S.W. Rosenbach, bidding in anticipation of finding a buyer, became the new owner for £15,400 (then equivalent to $77,000). After the sale, Rosenbach offered the manuscript at cost to the British Museum. The funds to keep this work in England could not be raised, so Rosenbach took the manuscript back to America. (Wolf and Fleming 287). It was then almost immediately sold to Eldridge Johnson for ‘cost plus ten’ (Wolf and Fleming 297), or for £30,000 according to Douglas-Fairhurst (396). Johnson kept the manuscript for 20 years, displaying it once at Columbia University’s Carroll Centernary Exhibition. He also published a facsimilie of it.

In 1946, Alice’s Adventures Under Ground was sold by Johnson’s heirs at a Parke-Bernet auction. Again, it was knocked down to Rosenbach, but this time for $50,000. A campaign was initiated by several American business men to raise the money to purchase the book. In 1848, they donated it to the British Museum as an expression of international good will (Wolf and Fleming and Bookleaves).

The manuscript currently is on permanent display in the British Museum.

Copyrights and translations

The British copyright on “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland” expired in 1907.

In Dodgson’s time, there were no international copyright laws as we know them now. This meant that foreign publishers were legally allowed to produce their own copies, without requiring permission or paying Dodgson or Macmillan for it. Although the first US edition (by Appleton) was published with permission and with payment for the original printed sheets, soon other unauthorized copies started to appear on the American market.

The very first translations, in German and French, were supervised by Dodgson and published by Macmillan. Dodgson selected the translators himself. By circulating copies among friends, colleagues, and advisors before having them printed, he tried to ascertain whether the verses, puns, and other elements were properly translated. The German translation appeared in February 1869. In the summer of that same year, the first French translation was published. A Swedish one appeared in 1870, and in 1872 an Italian one followed. There was also an abbridged Dutch version in 1875 in which the name ‘Alice’ was changed to ‘Marie’. In that same year the Danish translation was published. The Russion translation appeared in 1879. Unfortunately, the translations did not sell very well (Jaques and Gidders 109-113).

By now, the story has been translated into more than 174 different languages, including Korean, Japanese, Egyptian and Arabic. In 2015, 7,609 published editions have been identified all over the world, and the number keeps increasing (Lindseth and Tannenbaum).

After the Bible, Koran and Shakespeare, “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland” is the most frequently quoted and best known in the world.

Further reading

If you want to know more details about the transformation of the story from oral tales into a manuscript and into a printed version, or about printing and publishing details, I recommend reading the following excellent sources:

- Demakos, Matt. “From Under Ground to Wonderland“_. Knight Letter_, Spring 2012, Volume II Issue 18, nr. 88 and Demakos, Matt. “From Under Ground to Wonderland Part II“. Knight Letter, Winter 2012, Volume II Issue 19, nr. 89.These articles analyse in detail which additions were made and what was changed to the original manuscript “Alice’s Adventures Under Ground”, to become the published version “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland”.

- Jaques, Zoe and Eugene Giddens. Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass: A Publishing History. Routledge, 2016.

An in-depth overview of the publication process of both “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland” and “Through the Looking-Glass”, the creation of the illustrations, printing problems, pricing, publications abroad, and Carroll’s additional publications like ‘The Nursery Alice’. - Milevski, Robert J.. “A Note on Macmillan’s Lewis Carroll Bindings“. Knight Letter, Spring 2014, volume II issue 22, nr. 92.

About the different tickets (‘Bound by Burn’ stickers) that can be found in Carroll’s and MacMillan’s publications bound by James Burn & Co, which may help with identifying an edition. - Weaver, Warren. Alice in Many Tongues: The Translation of Alice in Wonderland, Martino Publishing, 1964.

A history of translations of Alice In Wonderland, and a (by now outdated) bibliography of foreign editions. For a more recent and complete bibliography, see “Alice in a World of Wonderlands“.

Works cited

Bookleaves. “Today in literary history”. January, page 3, www.geocities.com/RainForest/Andes/4354/janlithistp3.html.

Cohen, Morton N. Lewis Carroll. Interviews and Recollections. University of Iowa Press, 1989.

Collingwood, Stuart Dodgson. The life and letters of Lewis Carroll. Project Gutenberg, 6 March 2004, www.gutenberg.org/files/11483/11483-h/11483-h.htm.

Demakos, Matt. Cut-Proof-Print. From Tenniel’s Hands to Carroll’s Eyes. Stuffing the Teapot Press, 2021.

Douglas-Fairhurst, Robert. The Story of Alice. Lewis Carroll and the Secret History of Wonderland. Vintage, 2016.

Goodacre, S. et al. “The Works of Charles Dodgson: Alice”. The Lewis Carroll Society, 10 July 2017, lewiscarrollsociety.org.uk/pages/aboutcharlesdodgson/works/alice.html.

Goodacre, Selwyn. “Census of copies of the suppressed 1865 Alice”. “‘Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland’, an 1865 printing re-described and newly identified as the Publisher’s ‘File copy'” by Justin Schiller, The Jabberwocky, 1990.

Goodacre, Selwyn H.. “The Nursery “Alice” – A bibliographical Essay”. Jabberwocky, volume 4, no. 4, issue no. 24, Autumn 1975.

Hancher, Michael. The Tenniel illustrations to the ‘Alice’ books. The Ohio State Press, second edition, 2019.

Imholtz, Clare. “Notes on the early printing history of Lewis Carroll’s ‘Alice’ books”. The Book Collector. Volume 62, no. 2, summer 2013.

Jaques, Zoe and Eugene Gidders. Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass. A Publishing History. Ashgate Studies in Publishing History, Ashgate Publishing, 2016.

Lindseth, J.A. and A. Tannenbaum. Alice in a World of Wonderlands. Oak Knoll Press, 2015

Lindseth, J.A. and A. Hirshon (editors). Alice in a World of Wonderlands: The English Language Editions of the Four Alice Books Published Worldwide – Volume 2: Checklists and appendices. Atbosch Media, 2023

Lovett, Charlie. Letter in “Leaves from the Deanery Garden”. Knight Letter, Lewis Carroll Society of North America, fall 2015, Volume II, issue 25, no. 95.

Lovett, Charles C. and Stephanie B. Lovett. Lewis Carroll’s Alice ~ An Annotated Checklist of The Lovett Collection. Meckler, 1990.

Malcolm, Andy. “Alice’s Adventures in Xylography. The Brothers Dalziel and the Art of Engraving on Wood.” Knight Letter, volume III issue 8 no.108, Spring 2022.

O’Connor, Michael. “‘All in the golden afternoon.’ The origins of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland”. White Stone Publishing, The Lewis Carroll Society, 2012.

Ruizenaar, Henri. “The first Dutch Alice.” In: Lize’s Avonturen in het Wonderland, 1875 reissue by the Lewis Carroll Genootschap, Phlizz series No 2, 2021.

Wolf, Edwin and John Francis Fleming. Rosenbach: a biography. World Publishing Company, 1960.