the banned torture pictures of a journalist in Guantánamo | Andy Worthington (original) (raw)

Sami al-Haj is a journalist, but one unlike any other. For over six years, since December 15, 2001, when he was seized by Pakistani soldiers on the Afghan border, while on assignment as a cameraman for the Qatar-based broadcaster al-Jazeera, he has been in a disturbing but unique position: a trained journalist held as an “enemy combatant” on the frontline of the Bush administration’s “War on Terror,” first in Afghanistan, and then in Guantánamo.

Sami al-Haj is a journalist, but one unlike any other. For over six years, since December 15, 2001, when he was seized by Pakistani soldiers on the Afghan border, while on assignment as a cameraman for the Qatar-based broadcaster al-Jazeera, he has been in a disturbing but unique position: a trained journalist held as an “enemy combatant” on the frontline of the Bush administration’s “War on Terror,” first in Afghanistan, and then in Guantánamo.

For the first four years of his imprisonment, Sami, like all the prisoners processed through the US-run prisons in Kandahar and Bagram and then transferred to Guantánamo, had no voice. Until October 2004, when the first lawyers arrived at the prison following a momentous Supreme Court decision, three months earlier, that the prisoners had the right to challenge the basis of their detention, the only voices that emerged from Guantánamo were those of the few released prisoners — of the 200 released between 2002 and 2004 — who dared to speak out about their treatment.

Mostly these were the Europeans: the British, French, Danish, Swedish and Spanish prisoners released in 2004. Others — like the handful of Saudis released during this period — were explicitly prevented from speaking out, and others were advised not to do so. When 17 Afghans were released in April 2005, Chief Justice Fazel Shinwari told them at a press conference, “Don’t tell these people the stories of your time in prison because the government is trying to secure the release of others, and it may harm the chances of winning the release of your friends.” Others had been terrified into acquiescence. Yuksel Celik Gogus, a Turk released in November 2003, said after being freed, “They will come and take me away if I say what happened in Guantánamo.”

Sami’s opportunity to speak out came in early 2005, when he met his lawyer, Clive Stafford Smith of Reprieve, the legal action charity that currently represents 31 Guantánamo prisoners. The stories that Sami told him were shocking, as were those of many other prisoners. Echoing each other, despite cultural and linguistic differences, the prisoners reported extraordinary violence in the US-run prisons in Afghanistan. In describing their experiences at Guantánamo, they complained about the psychological torment of indefinite detention without charge or trial, the indiscriminate brutality of the teams of guards unleashed on prisoners for the most minor infringement of the rules, and the regime of torture — influenced by CIA counter interrogation techniques, and including prolonged isolation, the use of extreme heat and cold, the prolonged use of agonizingly painful stress positions, and the exploitation of phobias — that was prevalent in Guantánamo in 2003 and 2004 (as discussed in my book The Guantánamo Files).

Sami’s opportunity to speak out came in early 2005, when he met his lawyer, Clive Stafford Smith of Reprieve, the legal action charity that currently represents 31 Guantánamo prisoners. The stories that Sami told him were shocking, as were those of many other prisoners. Echoing each other, despite cultural and linguistic differences, the prisoners reported extraordinary violence in the US-run prisons in Afghanistan. In describing their experiences at Guantánamo, they complained about the psychological torment of indefinite detention without charge or trial, the indiscriminate brutality of the teams of guards unleashed on prisoners for the most minor infringement of the rules, and the regime of torture — influenced by CIA counter interrogation techniques, and including prolonged isolation, the use of extreme heat and cold, the prolonged use of agonizingly painful stress positions, and the exploitation of phobias — that was prevalent in Guantánamo in 2003 and 2004 (as discussed in my book The Guantánamo Files).

As Stafford Smith listened to Sami’s story, he was appalled to discover — beyond the tales of torture in Kandahar, Bagram and Guantánamo, and disturbingly unsubstantiated claims that he had “arranged for the transport of a Stinger anti-aircraft system from Afghanistan to Chechnya” — that every one of the hundred-plus interrogations to which he had been subjected in Guantánamo had focused solely on the administration’s attempts to turn him into an informant against al-Jazeera, to “prove” a connection between the broadcaster and Osama bin Laden that did not exist. As Stafford Smith noted bluntly and accurately in his book, The Eight O’Clock Ferry to the Windward Side: Seeking Justice in Guantánamo Bay, “Sami was a prisoner in the Bush Administration’s assault on al-Jazeera.”

Later events and disclosures only served to reveal more of the administration’s dark machinations. A reporter was killed in a US bomb attack on al-Jazeera’s headquarters in Baghdad in April 2003, and in 2006 it was reported that President Bush had, as Stafford Smith again described it in his book, “mooted the idea of bombing the al-Jazeera headquarters in Qatar.” As for Sami, it transpired that the US authorities had probably seized him because they had confused him with another man who had interviewed Osama bin Laden (although as Stafford Smith also noted, “name me a journalist who would turn down a bin Laden scoop”), and that, while Sami was on assignment in Afghanistan, his calls to his wife had been monitored by the CIA. “Extrapolating from the experience of a lowly cameraman like Sami,” Stafford Smith added, “it did not seem implausible that the phone of every al-Jazeera journalist was being tapped.”

The prisoners’ testimony was an enormous step forward in the wider understanding of the torture and abuse that was endemic in the administration’s “War on Terror” prisons, when their accounts, which were all subjected to a censorship process instigated by the Pentagon, often, and bewilderingly, emerged at the other end more or less intact.

In Sami’s case, his background in journalism added another dimension to these reports. In his book, Clive Stafford Smith recalled that when he asked Sami for information, he “would assemble important facts on almost any topic in the prison relying on the incredible prisoner bush telegraph.” He added, “Sami wrote reports about his treatment, the conditions at the prison and the pattern of his interminable interrogations. Perhaps two-thirds of these eventually made it through the censors, the others being held up for reasons that seemed little related to US security.”

These first-hand reports from behind the wire included reports on the religious abuse — primarily of the Qu’ran — that led to a series of hunger strikes and suicide attempts, and an assessment of the number of prisoners who were under 18 at the time of their capture (forty-five in total) which, as Stafford Smith wrote, sounded doubtful but was, in the end, probably something of an understatement. When the Pentagon finally released a prisoner list in 2006 — following a successful lawsuit pursued by the Associated Press — an analysis by Reprieve concluded that as many as sixty-four prisoners had been under 18 at the time of their capture (although it was difficult to state this with certainty, as many knew only the year of their birth, and not the day or the month).

As the years wore on, however, the irrepressible spirit recalled by all those who had met Sami before his imprisonment, and which also impressed Stafford Smith, was ground down by a particular despair that is perhaps unknowable to those who are not imprisoned without charge, without trial, with no contact with family or friends, and with no way of knowing when, if ever, this regime of almost total isolation will come to an end.

On January 7, 2007, the fifth anniversary of his detention without trial by the US, Sami embarked on a hunger strike, which continues to this day. In common with the small number of other persistent hunger strikers, he is strapped into a restraint chair twice a day and force-fed against his will. Clive Stafford Smith explained the brutality of the procedure, the reason the authorities are doing it, and also why it is illegal to do so, in an article last October.

“Medical ethics tell us that you cannot force-feed a mentally competent hunger striker, as he has the right to complain about his mistreatment, even unto death,” he wrote in the Los Angeles Times. “But the Pentagon knows that a prisoner starving himself to death would be abysmal PR, so they force-feed Sami. As if that were not enough, when Gen. Bantz J. Craddock headed up the US Southern Command, he announced that soldiers had started making hunger strikes less ‘convenient.’ Rather than leave a feeding tube in place, they insert and remove it twice a day. Have you ever pushed a 43-inch tube up your nostril and down into your throat? Tonight, Sami will suffer that for the 479th time.”

Even as he endured this twice-daily ordeal, Sami found the strength to put together a report on all the other hunger strikers in the prison — another extraordinary piece of frontline reporting that was published last March by the human rights group Cageprisoners. As the months passed, however, Stafford Smith noted a decline in his physical and mental health. Although he made an appeal for the BBC journalist Alan Johnston, who was kidnapped and imprisoned in Gaza for four months, and noted, “While the United States has kidnapped me and held me for years on end, this is not a lesson that Muslims should copy,” Clive Stafford Smith also noted in October, “Sami looked very thin. His memory is disintegrating, and I worry that he won’t survive if he keeps this up. He already wrote a message for his seven-year-old son, Mohammed, in case he dies here.”

Although Alan Johnston wrote a public letter to Sami after his own ordeal came to an end, Sami’s story has failed to permeate the Western media the way that it has in the Muslim world where, with the help of al-Jazeera, he has become Guantánamo’s most celebrated prisoner. Unfortunately, in the world of 24-hour rolling news, Johnston’s appeal on behalf of his fellow journalist was soon forgotten in the West, even though his words were both apt and heartfelt.

“While I was kidnapped recently in the Gaza Strip,” Johnston wrote, “fellow journalists from around the world joined the campaign mounted to try to secure my release, and of course you were among them. I was particularly grateful for your contribution given your own very difficult circumstances. In the light of my own experience of incarceration I am aware of how hard it must be for you and your family to endure your detention, and I very much hope that your case might be resolved soon. I understand that after some five years in Guantánamo you are calling to be allowed to answer any allegations that are being made against you. And of course I would always support any prisoner’s right to a fair trial.”

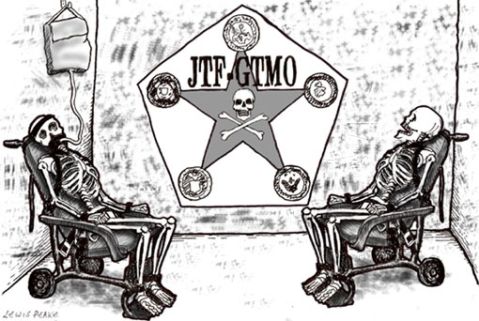

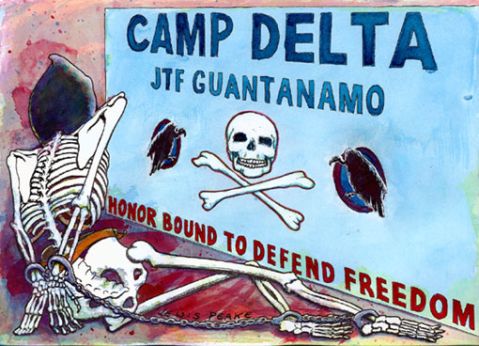

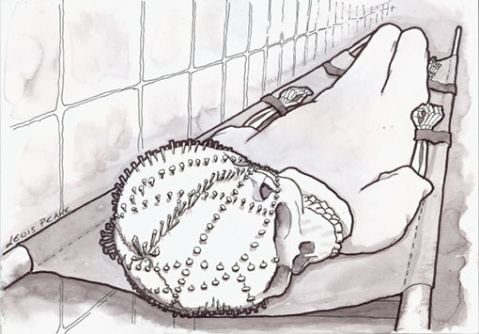

Despite Sami’s suffering, he continues to seek ways to publicize the plight of his fellow prisoners. During the most recent visit from his lawyers in February — with Cori Crider of Reprieve — he produced a number of morbid, and almost hallucinatory sketches illustrating his take on conditions in Guantánamo, which he described as “Sketches of My Nightmare.”

Fearing that they would be banned by the military censors, Crider asked him to describe each sketch in detail and when, as anticipated, the pictures were duly banned but the notes cleared, Reprieve asked political cartoonist Lewis Peake to create original works based on Sami’s descriptions.

“The first sketch is just a skeleton in the torture chair,” Sami explained. “My picture reflects my nightmares of what I must look like, with my head double-strapped down, a tube in my nose, a black mask over my mouth, strapped into the torture chair with no eyes and only giant cheekbones, my teeth jutting out — my ribs showing in every detail, every rib, every joint. The tube goes up to a bag at the top of the drawing. On the right there is another skeleton sitting shackled to another chair. They are sitting like we do in interrogations, with hands shackled, feet shackled to the floor, just waiting. In between I draw the flag of Guantánamo — JTF-GTMO — but instead of the normal insignia, there is a skull and crossbones, the real symbol of what is happening here.”

In recently declassified testimony, Sami described more of his recent experiences of the force-feeding process:

On the Monday before last [February 11] a white male came to do the force-feeding. They gave him only ten minutes training, then he did three of the eight men being fed that day, including me. He screwed the tube into my nose, not slowly, and not using lotion. I had flu at the time and my nostril was closed. It made it much harder. I was in the chair. I could barely talk, and my mouth was covered with the mask they put on. I was waving my hands.

“That’s very painful!” I eventually said. There were tears streaming down my face. “I am meant to do this to you,” the man said, harshly. “If you don’t like it, don’t go on strike.” He would not look me in the eye. He did not look in the least bit ashamed. He never said sorry, or paused when I was in pain. I almost thought he seemed happy that he was doing it.

They used my feeding tube for another man last Monday [February 18]. This, even though they have marked the boxes for each tube. I have been getting a sore larynx, maybe from the infection of another person using my tube. I requested a spray but it was denied.

Sami’s second sketch is his take on the familiar JTF-GTMO sign outside the prison. “This time,” he explained, “the hooded skeleton is in a three-piece suit [the prisoners’ term for being shackled at the wrists, ankles and waist]. The head is totally blacked out. The wrists are shackled at the back, with chains running down the legs. There are very elaborate arm bones, leg bones and the spine. And again the flag, the Jolly Roger of JTF-GTMO with a diabolical smile on the skull.”

For his next sketch, Sami shifted his attention to the prison hospital. “There is a third sketch, which is about the Hospital,” he said. “Again it is a skeleton, but with a face this time. The top of the skull is dotted with tracks, tracks of pain. This is the hospital gurney prisoner. He sits completely still, his hands and feet shackled to the side of the bed.”

In his testimony, recently released, Sami has elaborated on his experiences of the hospital:

I am very concerned about having cancer. I have had blood in my urine for a long time. They refused to believe me until I showed them urine in a container that had red in it. Since then they have had seven positive tests for blood in my urine.

I have a pain all across my chest and stomach, and in both kidneys. To begin with they thought it might be a kidney stone, but I had a scan for that. They did not give me the results for two weeks, and I worried all that time. It was negative.

So then they did a second scan with a tracer in the blood. This time, they did not tell me the results for two months. Again, I was left to worry about what might be wrong with me. Again, eventually a doctor came to see me, a black male, about 40 years old, clean shaven, in a uniform without rank on it. He saw me for only give minutes. He began decently, but then got rather hostile. He told me the test was negative, meaning that there was no kidney stone. “From my experience,” the doctor said to me, “I think it’s cancer.”

They then said that the next time a doctor would be coming with the appropriate expertise would be in May. Nobody would be coming before that, and he might not come even then. “You will leave me worrying about this for months?” I asked. “I don’t have the necessary equipment,” said the doctor. He apparently thought the prisoners were not as important as the soldiers in his care. “I don’t mind if you suffer or not,” he said. “It’s not my problem. I’m not here for you.” He left.

I worried too much after this. For three days I got barely any sleep. I was worrying that maybe I was dying. Then the brothers around me said, perhaps they are just telling you this, just trying to break your strike. I took some heart from this. But I still worry, as Abdul Razzaq died of cancer here, and it was a very painful death [Abdul Razzaq Hekmati, an Afghan who died on Dec.30].

I have all the other medical problems too. Really, I have pain almost everywhere –- all over. I have pain everywhere. It’s hard to identify one thing as it’s all over. My back, kidneys, chest, stomach, knee, I even have hemorrhoids. When I do get released, I am going to need to be taken to hospital right away.

For his final sketches, Sami focused on the doctors’ role in the force-feeding process. “All they care about is the prisoner’s weight,” he explained. “’Are you sick? Are you in pain?’ Who cares? It is all about the number on the scale. At the top of the drawing there is a skeleton again, but this time without hands or feet. The top of the head, the cranium, even the eyes are gone. Our lives depend on the doctors, but we get nothing from them. So we’re going mad. A man who is mad has no mind, but he still has a heart. We’re all going mad here. The skeleton is strapped to a gurney, there’s a tube and a pump, and the gurney is on a scale. It reads 98 lbs. But that’s with the weight of the gurney, and maybe the soldier’s pushing down on the skeleton a bit also.”

He added, “As they prepare the feeding they don’t use gloves. When they take the tube out, things come out of the nose, but the people are strapped to the chair, and cannot do anything to clean the revolting tube. There are psychological teams all around, all keen to work out what the impact of this is on the prisoner.”

In the fifth sketch, Sami explained the meaning of the bloated body, noting that, even if the prisoner’s weight were to rise due to force-feeding, he would still be losing his mind. “In the second half of this drawing the prisoner is inflated,” he said. “The man is strapped to the gurney, and the weight on the scale reads 250 lbs. He has filled out, there are rolls of fat on his belly, but he is still mad. The pumps are all hooked up, forcing food into him. But the top half of his head is still vacant.”

The last of his declassified notes add a disturbing conclusion to the story of the doctors’ involvement in the force-feeding process, and the horrendous isolation and deprivation that still prevail in Guantánamo:

We met recently with a senior female doctor from the hospital. “Only if you break your strike can we give you medical care,” she told those of us on hunger strike. “Otherwise we cannot help you.” Some have now broken their strike. Four men are very sick, and were suffering too badly. But the truth is that they have given no help even to those who stop.

I am having bone problems. The cold is bad. I am on disciplinary for being on strike, so I get a plastic blanket at 10 pm, at least three hours after our last prayer time. Every other day I hardly get to sleep anyway, as rec [recreation time] is in the middle of the night.

For eight days I had the same clothes. I have not been given proper toothpaste for two years and seven months now. I am allowed a fingerbrush for just five minutes each day, and it doesn’t reach the back of my mouth. I am not allowed a prayer rug. I am not allowed a prayer cap. I am not allowed my prayer beads. I am not allowed any holy book except for the Qur’an. I have no books to read. The last book I was allowed was in December 2006, before I began my strike.

All I have are orange clothes, flip flops, an isomat, a Qur’an, and a bottle of water. I suppose I should think myself lucky. Another of the men here has been disciplined by having even his isomat take away –- for a whole year. Another man has lost his right to a water bottle for a whole year. All this made another man so upset that he tried to hang himself.

Andy Worthington is the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press, distributed by Macmillan in the US, and available from Amazon — click on the following for the US and the UK), and was the Communications Officer for Reprieve in 2008. To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to my RSS feed, and see here for my definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, published in March 2009.

A version of this article was published on AlterNet, as The Torture Drawings the Pentagon Doesn’t Want You to See.

See here for further articles about Sami, dealing with his release in May 2008 and his subsequent activities.

For a sequence of articles dealing with the hunger strikes at Guantánamo, see Shaker Aamer, A South London Man in Guantánamo: The Children Speak (July 2007), Guantánamo: al-Jazeera cameraman Sami al-Haj fears that he will die (September 2007), The long suffering of Mohammed al-Amin, a Mauritanian teenager sent home from Guantánamo (October 2007), Guantánamo suicides: so who’s telling the truth? (October 2007), Innocents and Foot Soldiers: The Stories of the 14 Saudis Just Released From Guantánamo (Yousef al-Shehri and Murtadha Makram) (November 2007), A letter from Guantánamo (by Al-Jazeera cameraman Sami al-Haj) (January 2008), A Chinese Muslim’s desperate plea from Guantánamo (March 2008), The forgotten anniversary of a Guantánamo suicide (May 2008), Binyam Mohamed embarks on hunger strike to protest Guantánamo charges (June 2008), Second anniversary of triple suicide at Guantánamo (June 2008), Guantánamo Suicide Report: Truth or Travesty? (August 2008), Seven Years Of Guantánamo, And A Call For Justice At Bagram (January 2009), British torture victim Binyam Mohamed to be released from Guantánamo (January 2009), Don’t Forget Guantánamo (February 2009), Who’s Running Guantánamo? (February 2009), Obama’s “Humane” Guantánamo Is A Bitter Joke (February 2009), Forgotten in Guantánamo: British resident Shaker Aamer (March 2009), Guantánamo’s Long-Term Hunger Striker Should Be Sent Home (March 2009). Also see the following online chapters of The Guantánamo Files: Website Extras 2 (Ahmed Kuman, Mohammed Haidel), Website Extras 3 (Abdullah al-Yafi, Abdul Rahman Shalabi), Website Extras 4 (Bakri al-Samiri, Murtadha Makram), Website Extras 5 (Ali Mohsen Salih, Ali Yahya al-Raimi, Abu Bakr Alahdal, Tarek Baada, Abdul al-Razzaq Salih).

For a sequence of articles dealing with the use of torture by the CIA, on “high-value detainees,” and in the secret prisons, see: Guantánamo’s tangled web: Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, Majid Khan, dubious US convictions, and a dying man (July 2007), Jane Mayer on the CIA’s “black sites,” condemnation by the Red Cross, and Guantánamo’s “high-value” detainees (including Khalid Sheikh Mohammed) (August 2007), Waterboarding: two questions for Michael Hayden about three “high-value” detainees now in Guantánamo (February 2008), Six in Guantánamo Charged with 9/11 Murders: Why Now? And What About the Torture? (February 2008), The Insignificance and Insanity of Abu Zubaydah: Ex-Guantánamo Prisoner Confirms FBI’s Doubts (April 2008), Guantánamo Trials: Another Torture Victim Charged (Abdul Rahim al-Nashiri, July 2008), Secret Prison on Diego Garcia Confirmed: Six “High-Value” Guantánamo Prisoners Held, Plus “Ghost Prisoner” Mustafa Setmariam Nasar (August 2008), Will the Bush administration be held accountable for war crimes? (December 2008), The Ten Lies of Dick Cheney (Part One) and The Ten Lies of Dick Cheney (Part Two) (December 2008), Prosecuting the Bush Administration’s Torturers (March 2009), Abu Zubaydah: The Futility Of Torture and A Trail of Broken Lives (March 2009), Ten Terrible Truths About The CIA Torture Memos (Part One), Ten Terrible Truths About The CIA Torture Memos (Part Two), 9/11 Commission Director Philip Zelikow Condemns Bush Torture Program, Who Authorized The Torture of Abu Zubaydah?, CIA Torture Began In Afghanistan 8 Months before DoJ Approval, Even In Cheney’s Bleak World, The Al-Qaeda-Iraq Torture Story Is A New Low (all April 2009), Ibn al-Shaykh al-Libi Has Died In A Libyan Prison, Dick Cheney And The Death Of Ibn al-Shaykh al-Libi, The “Suicide” Of Ibn al-Shaykh al-Libi: Why The Media Silence?, Two Experts Cast Doubt On Ibn al-Shaykh al-Libi’s “Suicide”, Lawrence Wilkerson Nails Cheney On Use Of Torture To Invade Iraq, In the Guardian: Death in Libya, betrayal by the West (in the Guardian here) (all May 2009), Lawrence Wilkerson Nails Cheney’s Iraq Lies Again (And Rumsfeld And The CIA), and WORLD EXCLUSIVE: New Revelations About The Torture Of Ibn al-Shaykh al-Libi (June 2009). Also see the extensive archive of articles about the Military Commissions.

For other stories discussing the use of torture in secret prisons, see: An unreported story from Guantánamo: the tale of Sanad al-Kazimi (August 2007), Rendered to Egypt for torture, Mohammed Saad Iqbal Madni is released from Guantánamo (September 2008), A History of Music Torture in the “War on Terror” (December 2008), Seven Years of Torture: Binyam Mohamed Tells His Story (March 2009), and also see the extensive Binyam Mohamed archive. And for other stories discussing torture at Guantánamo and/or in “conventional” US prisons in Afghanistan, see: The testimony of Guantánamo detainee Omar Deghayes: includes allegations of previously unreported murders in the US prison at Bagram airbase (August 2007), Guantánamo Transcripts: “Ghost” Prisoners Speak After Five And A Half Years, And “9/11 hijacker” Recants His Tortured Confession (September 2007), The Trials of Omar Khadr, Guantánamo’s “child soldier” (November 2007), Former US interrogator Damien Corsetti recalls the torture of prisoners in Bagram and Abu Ghraib (December 2007), Guantánamo’s shambolic trials (February 2008), Torture allegations dog Guantánamo trials (March 2008), Former Guantánamo Prosecutor Condemns “Chaotic” Trials in Case of Teenage Torture Victim (Lt. Col. Darrel Vandeveld on Mohamed Jawad, January 2009), Judge Orders Release of Guantánamo’s Forgotten Child (Mohammed El-Gharani, January 2009), Bush Era Ends With Guantánamo Trial Chief’s Torture Confession (Susan Crawford on Mohammed al-Qahtani, January 2009), Forgotten in Guantánamo: British Resident Shaker Aamer (March 2009), and the extensive archive of articles about the Military Commissions.