As You Read This, Guantánamo Prisoner Ahmed Rabbani Has Been On A Hunger Strike for 2,846 Days | Andy Worthington (original) (raw)

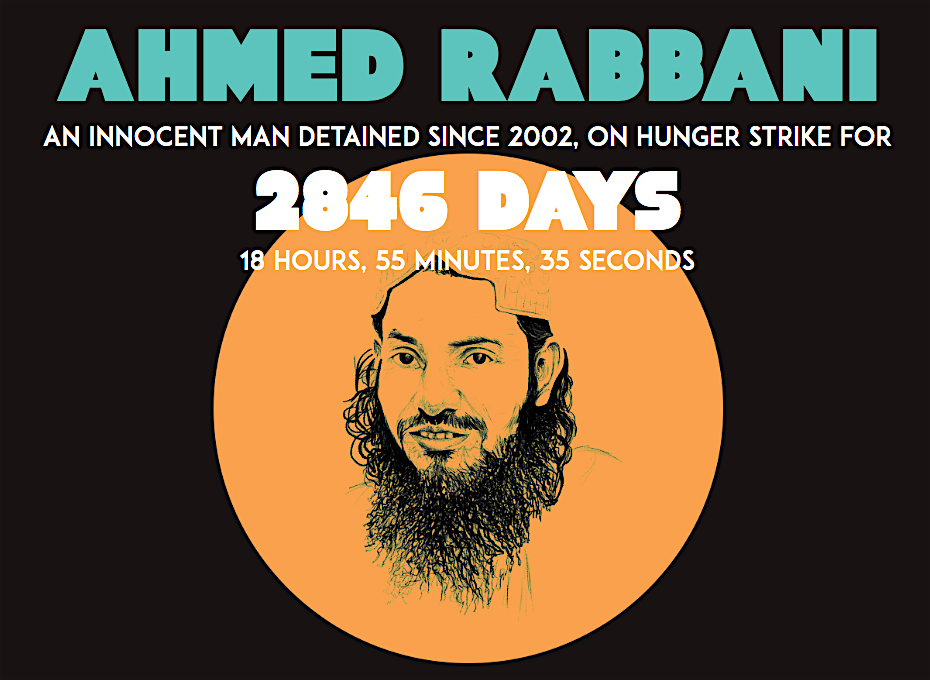

An image from the website, “Gitmo Hunger Strikes,” set up by Reprieve to highlight the plight of their client, Ahmed Rabbani.

Please support my work as a reader-funded journalist! I’m currently trying to raise $2500 (£2000) to support my writing and campaigning on Guantánamo and related issues over the next three months. If you can help, please click on the button below to donate via PayPal.

With the media spotlight hopefully being shone anew on the prison at Guantánamo Bay, now that Joe Biden has been elected as the US president, it is to be hoped that, as I explained in my recent article, President Elect Biden, It’s Time to Close Guantánamo, arrangements will be made to release the five men still held who were unanimously approved for release by high-level government review processes under President Obama, and that there will be an acceptance within the Biden administration that holding 26 other men indefinitely without charge or trial is unacceptable.

These 26 men — accurately described as “forever prisoners” by the media — were recommended either or for prosecution, or for ongoing imprisonment without charge or trial, on the basis that they were “too dangerous to release,” even though it was acknowledged that insufficient evidence — or insufficient untainted evidence — existed for them to be charged, by the first of Obama’s two review processes, the Guantánamo Review Task Force, in 2009.

Four years later, the 26 — along with 38 others — were deemed eligible for a second review process, the Periodic Review Boards. Unlike the first process, which involved officials assessing whether prisoners should be freed, charged or held on an ongoing basis without charge or trial, the PRBs were a parole-type process, in which the men were encouraged to express contrition for the activities in which they were alleged to have been involved (whether those allegations were accurate or not), and to present credible proposals for a peaceful and constructive life if released.

In 38 cases, conducted between November 2013 and the end of Obama’s presidency, the PRBs led to recommendations that the prisoners in question be released, and all but two of them were freed before Obama left office. The 26 others, however, remain in a disturbing limbo. Under Trump, when the PRBs continued, but failed to deliver a single recommendation for release, they concluded that the process had become a sham, and, understandably, boycotted it.

Now, however, Joe Biden has the opportunity to look at their cases again, and in the months to come (both here and on the Close Guantánamo website), I will be making the case that, seven years after the PRBs started, and nearly 19 years since Guantánamo opened, it is unacceptable that these men continue to be consigned to indefinite imprisonment without charge or trial — with the PRBs concluding, in their still-ongoing reviews, that “continued law of war detention … remains necessary to protect against a continuing significant threat to the security of the United States” — when the basis for those decisions is often either faulty, or demonstrably over-cautious.

The case of Ahmed Rabbani

In President Elect Biden, It’s Time to Close Guantánamo, I looked at a few of these cases, and I’ll be following up on them, and also looking at others, in the months to come, but for now I’d like to focus on the case of Ahmed Rabbani, a Pakistani of Rohingya origin, seized with his elder brother, Abdul Rahim, in Karachi in September 2002, and held and tortured in CIA “black sites” for two years until their transfer to Guantánamo in September 2004.

Ahmed is a long-term hunger striker, and his lawyers, at the NGO Reprieve, recently launched a website, Gitmo Hunger Strikes, focusing on his case, and showing, in real time (as the image at the top of this article shows), how long he has been on a hunger strike, and force-fed by the authorities, how much he weighs — just 39 kilos (or 6 stone 2 pounds) — and how much of his body weight he has lost. Please do share it if you find it unconscionable that Ahmed Rabbani has been hunger striking for nearly eight years, and that the US government can get away with holding someone who must look like he is in a concentration camp.

Below I’m cross-posting an article by Ahmed Rabbani that was published by the Pakistani newspaper Dawn a few months ago, in which he discusses his hunger strike, and also mentions his son Jawad, who, as he says, is 17, and who he has “never had the chance to touch.”

Jawad Rabbani, Guantánamo prisoner Ahmed Rabbani’s 17-year old son, who has never met his father. The photo is a screenshot from a video on the Independent Urdu website.

Just two weeks ago, the Independent Urdu spoke to Jawad, who told reporter Zafar Syed, in an article translated into English by the UK-based Independent website, “I have never met my father, nor has he ever met me. I found out about my father’s case from Google when I was 12 or 13 years old. I read about his story on Wikipedia.”

He added, ”I was born five or six months after my father went to prison. When I was younger, I would never tell my friends who my father was or where he was. I used to say he was dead. When we first spoke to him [on Skype], he said he was in prison. I asked him, ‘Why are you in prison? Only bad people go to prison’ at which he laughed.”

In a letter to the Independent Urdu, Rabbani wrote that, since “release from this prison is not possible in this life; I wish to be released from this prison through death,” adding, “The Americans are afraid that I shall starve to death, so they force-feed me every day, and this is no less than torture.”

As he also stated, “I am nothing but skin and bones and I move around with the help of a cane. I’m only 51 but I look like a 95 year-old. I saw my shadow through the window and thought I might be in the movie ‘Unbroken,’ which showed American pilots who died of starvation as prisoners of war in World War II.”

On the Gitmo Hunger Strikes page, his lawyers at Reprieve describe how he “was born and grew up in Saudi Arabia, before moving to Karachi, where he ran a small taxi service,” and note that the Pakistan authorities “sold [him] for a $5,000 bounty with the story that he was actually Hassan Ghul, a notorious terrorist, to the American authorities.” It is certainly true that Ahmed Rabbani was mistaken for Hassan Ghul, but it may not be strictly true that he was just a taxi driver.

The brothers are accused by the US of being significant al-Qaeda operatives, but the truth seems to be that, needing a steady income, they worked for Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, the alleged mastermind of the 9/11 attacks, but did not have any organizational or leadership role in al-Qaeda whatsoever. In fact, as I explained in my book The Guantánamo Files, published in 2007, in 2006 a Pakistani intelligence official specifically stated, with reference to the brothers, that, “Although they have served for Khalid Sheikh as his employees, they were not linked with al-Qaeda.”

12 years ago, Salim Hamdan, a Yemeni who had worked as a driver for Osama bin Laden in Afghanistan, was subjected to a military commission trial, which found him guilty of providing material support for terrorism. The judge, however, only gave him a five-month sentence, and he was home before the end of the year. Later, his conviction was overturned, as an appeals court recognized that providing material support for terrorism was not a war crime.

12 years after Salim Hamdan went home, it is deeply shocking to me that two other men who also worked as paid employees for individuals connected to al-Qaeda, but had no decision-making role whatsoever, and were not regarded by Pakistant intelligence as al-Qaeda members, continue to be held, have not been put on trial, and are repeatedly prevented from being released — because the panel members in their parole-type process, which has no legal standing, keeps determining that “continued law of war detention … remains necessary to protect against a continuing significant threat to the security of the United States.”

Below is Ahmed Rabbani’s article for Dawn, which I hope you find useful.

Wasting away

By Ahmed Rabbani, Dawn, September 22, 2020

On 21 August, 2006, records show that I weighed 73 kilos [11 stone 7 pounds]. When I was weighed a week ago, the scale registered just 39 kilos [6 stone 2 pounds]. In the last 14 years at Guantánamo Bay, nearly half of me has disappeared.

In total, it has now been 18 years since I was kidnapped and handed over to US forces, to be tortured in Afghanistan and flown halfway across the world to this island gulag. Of the original 780 prisoners, 740 have been released, but here I am, thousands of miles from my wife and children — including Jawad, who is 17, and who I have never had the chance to touch.

Can you imagine one of your children being almost adult, yet you have never touched him? My hunger strike is a peaceful protest against this indefinite detention without trial. Nobody suggests I have ever committed a crime.

The US military are paranoid about people escaping, though it is hard to think where I might go: there are 100 soldiers for each detainee, along with the second largest landmine field in the world after Korea, plus the shark infested Caribbean sea.

Yet I have an escape plan: I am going to gradually vanish. I like to think that almost half of me has found freedom already, though I am so thin I can now feel my thumb and finger when I pinch where my stomach ought to be.

This is despite them force feeding me with tins of Ensure, deliberately hurting me in the process. Twice a day they take me to the ‘torture chair.’

They say I go voluntarily, but if I do not walk there in my shackles, they send a team of guards to throw me to the floor and violently drag me out of my cell — and then punish me afterwards for refusing to comply. I may as well get there on my own two feet.

They strap me in and a military nurse uses a 110-centimetre tube on me. It is painful and I get a splitting headache each time they do it, but I am used to that. What I can never accept is being used as a sub-human guinea pig for the nurses to learn the job. Soldiers come and go every few months, but I remain. I try to teach them how to do it, as I am an expert by now: after seven years of hunger striking, on and off, I have probably had a tube stuck up my nose more times than anyone else on the planet.

In each new six-month deployment there are one or two who can’t get it round the top of my nose, or send the tube into my lungs instead of my stomach. (They have to blow air in first to show where it went — or else I would drown in protein shake). One soldier I have at the moment is just untrainable, I don’t think she’ll ever get it right, no matter how many times she tries.

Mine is a fairly desperate strategy, particularly for someone like me. Back in another world, before I was kidnapped, when I was not driving a taxi around Karachi I would be cooking for my friends and family. Preparing and eating food is one of life’s great pleasures, and I do not give it up lightly.

To distract myself from my misery, I have been working on a cookbook. My family is originally from the Rohingya minority that has suffered from Burmese genocide, so we are used to being mistreated. One of my dishes is Rohingya ‘Strappado Chicken,’ so named as you must hang the chicken rather like they dangled me in the ‘Dark Prison.’

A ‘Guantánamo Diet Book’ would be rather shorter — you just stop eating. What else am I supposed to do? What would you do if you had lost 18 years of your life, with no end in sight? The freedom to refuse food — to starve myself in protest against this terrible injustice — is the only freedom I have left.They tell me that I am not ‘cooperating’ with them. They told my lawyers if I testified against some of the high-value detainees, I could go home.

But they wanted me to repeat what I said during 540 days in their ‘Dark Prison’ in Kabul, where they hung me from an iron bar in a pitch dark pit. (That is a form of torture that was called ‘Strappado’ 500 years ago in the Middle Ages, yet is sadly something the US used on me in the 21st century — the pain as your shoulders gradually dislocate is excruciating).

But I have lines I will never cross, and I said I could not ‘cooperate’ in repeating lies that I made up to get them to stop torturing me.

I know nothing about terrorism, and it is ironic that unless I swear to these lies, I am labelled a terrorist myself. I’ve done a lot of ‘cooperating’ — following their stupid rules or taking part in their “Periodic Review Board” even though President Donald Trump tweeted he would not let anyone go — but no matter how much I do this, I am still here.

So I will maintain my peaceful protest, aiming to lose another 17 pounds, down to about 70. I suppose in the end, if I keep going, I will not survive. But I was recently 51 years old, and have had the prime of my life taken from me. If they won’t let me return to my wife and children soon, the rest of me may as well go home in a box.

* * * * *

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and see the latest photo campaign here) and the successful We Stand With Shaker campaign of 2014-15, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here, or here for the US, or you can watch it online here, via the production company Spectacle, for £2.55), and for his photo project ‘The State of London’ he publishes a photo a day from eight years of bike rides around the 120 postcodes of the capital.

Andy Worthington is a freelance investigative journalist, activist, author, photographer, film-maker and singer-songwriter (the lead singer and main songwriter for the London-based band The Four Fathers, whose music is available via Bandcamp). He is the co-founder of the Close Guantánamo campaign (and see the latest photo campaign here) and the successful We Stand With Shaker campaign of 2014-15, and the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison and of two other books: Stonehenge: Celebration and Subversion and The Battle of the Beanfield. He is also the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film, “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo” (available on DVD here, or here for the US, or you can watch it online here, via the production company Spectacle, for £2.55), and for his photo project ‘The State of London’ he publishes a photo a day from eight years of bike rides around the 120 postcodes of the capital.

In 2017, Andy became very involved in housing issues. He is the narrator of the documentary film, ‘Concrete Soldiers UK’, about the destruction of council estates, and the inspiring resistance of residents, he wrote a song ‘Grenfell’, in the aftermath of the entirely preventable fire in June 2017 that killed over 70 people, and he also set up ‘No Social Cleansing in Lewisham’ as a focal point for resistance to estate destruction and the loss of community space in his home borough in south east London. For two months, from August to October 2018, he was part of the occupation of the Old Tidemill Wildlife Garden in Deptford, to prevent its destruction — and that of 16 structurally sound council flats next door — by Lewisham Council and Peabody. Although the garden was violently evicted by bailiffs on October 29, 2018, and the trees were cut down on February 27, 2019, the resistance continues.

To receive new articles in your inbox, please subscribe to Andy’s RSS feed — and he can also be found on Facebook (and here), Twitter, Flickr and YouTube. Also see the six-part definitive Guantánamo prisoner list, The Complete Guantánamo Files, the definitive Guantánamo habeas list, the full military commissions list, and the chronological list of all Andy’s articles.

Please also consider joining the Close Guantánamo campaign, and, if you appreciate Andy’s work, feel free to make a donation.

- Posted in Conditions at Guantanamo, Extraordinary rendition and secret prisons, Guantanamo, Guantanamo campaigns, Guantanamo lawyers, Guantanamo tribunals, Hunger strikes in Guantanamo, Joe Biden, Pakistanis in Guantanamo Tagged Abdul Rahim Ghulam Rabbani, Ahmed Rabbani, Black sites, Guantanamo, Hunger strikes, Joe Biden, Periodic Review Boards, Torture

- Permanent Link