The key moments that shaped the British press (original) (raw)

The newspaper industry is bracing itself for Lord Justice Leveson's report into press ethics at the end of the month, but the battle to control the press is centuries old. Here Steve Hewlett recalls the key moments in the struggle for press freedom.

The pillorying of John Lilburne

In 1637, protestant radical and small-time printer John Lilburne was thrown into Fleet Prison in London. The following year he was sentenced to be tied to the back of a cart and whipped all the way to Westminster where he was to be pilloried.

His appearance at the Star Chamber in February 1638 so infuriated the court that the charge of "insufferable disobedience and contempt" was added to his sheet.

His crime? Illegal printing.

Image caption,

John Lilburne - or Freeborn John- was a hero to many non-conformists

All presses required licensing and Lilburne's pamphlets satirising state religion were effectively unpublishable in England. So he printed them in Holland, with inevitable consequences when he distributed them back home.

"The people of London lined the route and as he processed along Fleet St and down the Strand being thrashed he called out and continued to express the things for which he was being punished," says historian Ben Wilson.

"At Westminster he was placed in the pillory and he read from his publication, so was gagged till his mouth bled. Then he stamped his feet to carry on his defiance. No one could stop John Lilburne."

Press licensing was abandoned in 1695, but punishments for seditious libel continued.

Novelist Daniel Defoe was one such recipient. His satirical pamphlet The Shortest Way with Dissenters brought him a hefty fine, prison sentence and three sessions in the pillory at Charing Cross.

The stamp tax

Ever fearful of the consequences of a free press, in 1712 the state introduced a stamp tax on newspapers and further duties on paper and advertising.

The purpose was to make newspapers sufficiently expensive to restrict their circulation to only the well off and avoid the perils of mass circulation.

The authorities made no attempt to hide their motives, according to media historian Professor James Curran.

"The people who introduced [these taxes] said 'we want the people owning the press to be people of property, capital and respectability and we want to prevent the 'outdoors', as they were called, from being able to buy newspapers.'"

The press continued to grow nonetheless, but only among the middle class, not the poor.

William Hone and blasphemous libel

A century on and the state's armoury of legislation to control what was published remained pretty fearsome.

It was a criminal offence, for example, to publish blasphemous or seditious libel. And there was a twist - if what you said was true, that just made the libel worse.

In 1817, William Hone, a small-time London publisher and radical, regularly exposed corruption in government and the justice system. But a parody of the Lord's Prayer satirising lickspittle MPs saw Hone arrested and his weekly newssheet shut.

Penniless, and facing charges of blasphemous libel at London's Guildhall, he defended himself.

But he turned the trial in December 1817 into a triumph, according to Wilson.

"You get one of those brilliant situations that satirists love, where the people [Hone] was mocking have to read out the satires aimed against them."

The Guildhall crowd started laughing. Attorney General Lord Ellenborough demanded they stop - but without success.

Eventually Hone was acquitted of all charges.

This was a watershed, believes Wilson.

"It shows that these laws, that had once been so effective, no longer worked."

WT Stead and 'the m a iden tribute of modern babylon'

As the press grew through the 19th Century, one way for papers to escape the influence of political parties and their bribes was to seek mass circulation and commercial sustainability.

The editor of the Pall Mall Gazette in the 1880s, WT Stead, was a high-minded social reformer - but with a very sharp tabloid eye.

He took on one of Victorian London's dirtier little secrets - child prostitution.

Not content with moralistic comment pieces, in 1885, Stead actually bought a 13-year-old girl, and then wrote a series of articles about it, under the banner "the maiden tribute of modern babylon".

It was a hugely controversial stunt which outraged polite society - and Stead was sent to prison for abduction - but ultimately it was a brilliantly effective piece of raucous popular journalism.

"The Conservative government of the day were having their postbags stuffed with letters from indignant people saying 'how can the age of consent only be 13?'" says Stead's biographer, Will Sydney Robinson.

Legislation was hurried through Parliament, raising the age of consent to 16.

'The liberty to deal in filth'

In 1857, divorce was legalised and the burgeoning press had a field day reporting the adulterous shenanigans of high society couples.

After WWI, the divorce rate quadrupled and young society ladies were increasingly willing to discuss their private lives in public courts.

In one celebrated case in 1922, George Hugo Russell, a senior politician, sought divorce from his wife Christabel. He alleged that she had become pregnant even though she had refused to consummate their marriage.

In challenging his petition, Christabel alleged that her husband had sleep-walked into her bedroom and slept with her without either of them being aware of it.

Eventually legions of embarrassed aristocrats forced the government to act and in 1926 reporting the salacious details of divorce cases was outlawed.

The MP introducing the new law to Parliament dismissed the argument for press freedom saying "the only liberty at question is the liberty to deal in filth".

Controlling the press barons

Newspapers grew in scale and influence into the 20th Century and so did the people who owned them.

The press barons - larger than life characters determined to have their say in politics - were born.

Image caption,

The influential Lord Beaverbrook held government ministerial positions during both world wars

At the post-war general election in 1945, Lord Beaverbrook's Daily Express and Lord Rothermere's Daily Mail lined up decisively against Labour - who duly went on to win a landslide victory.

Incensed, however, by the way they felt treated, a group of backbench Labour MPs persuaded prime minister Clement Atlee to set up a Royal Commission on the Press to look at bias and concentration of ownership.

In the end, the Royal Commission found that there were sufficient press owners and refused to recommend action against the barons. What they did do was suggest a General Council on the Press to oversee press standards.

The Profumo affair

Image caption,

At the heart of the scandal, Christine Keeler (r) and friend Mandy Rice-Davies

In 1963, the War Minister John Profumo's affair with call girl Christine Keeler was exposed.

Mr Profumo was forced to resign from the Cabinet for lying to the House of Commons over his affair with Keeler, who was also seeing a Russian KGB officer. The resulting scandal became a cause celebre for an increasingly assertive press.

Press historian Roy Greenslade sees the Profumo affair as a watershed.

"The view of the press is that the Establishment has lots of secrets and gradually you're seeing journalists doing things their proprietors wouldn't necessarily be pleased with.

"You're getting much more aggressive Sunday newspapers, in terms of the News of the World and the Sunday Pictorial, really hunting down stories, but to get their stories they misbehave in an amazing fashion."

Then in 1969, the News of the World bought and serialised Keeler's account of the Profumo affair.

The Press Council condemned the paper but its new owner responded by attacking the council's decision as unjust, dismissing them as an arm of the Establishment. His name? Rupert Murdoch.

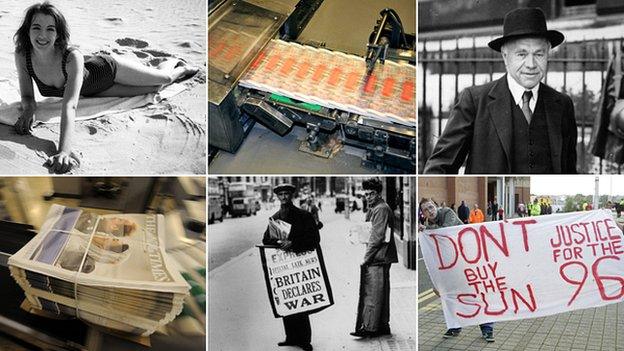

The 1980s: The Wild West

In the 1980s, changing technology and increased competition for readers and stories created what might be called the roaring 1980s.

At Murdoch's Sun, a buccaneering new editor, Kelvin Mackenzie, pioneered a risk-taking, aggressive approach to tabloid journalism.

This brought big sales but provoked increased public concern over widespread invasions of privacy.

Image caption,

The Sun is still subject to a boycott in parts of Liverpool

Newspapers were accused of insensitivity after the air crash in Lockerbie for hounding the entertainer Russell Harty in his last days and much more besides. They published photographs of a rape victim, and offered money to the family of the Yorkshire Ripper for stories.

Though the tabloids also scored many genuine successes, in April 1989 a line was crossed.

Just a few days after the Hillsborough disaster - in which 96 Liverpool fans were killed - the Sun blamed Liverpool fans for what went wrong.

The paper then reported the false story that fans had attacked and urinated on the police, headlined "The Truth". The same week, amid ongoing calls for legislation, the Home Office initiated another inquiry into the behaviour of the press under David Calcutt QC.

The last chance saloon

By this time, the press had tumbled through the doors of what one minister, David Mellor, dubbed the "last chance saloon". David Calcutt QC's inquiry reported in June 1990, expressing grave concerns about invasions of privacy and the lack of effective remedies.

He recommended scrapping the now discredited Press Council and replacing it with a new Press Complaints Commission.

It was to be the last chance for self-regulation and subject to a review of its effectiveness after 18 months. If found wanting, statutory regulation would follow. That would mean a fully independent tribunal chaired by a judge with powers to fine papers and compensate victims.

Under pressure, the newspaper owners finally agreed to a code of conduct - 41 years after it was first recommended by the first Royal Commission on the Press - and this formed the basis for the PCC's work.

In 1993, Calcutt did his 18-month review, judging the Press Complaints Commission to have failed, and recommending the setting up of a statutory tribunal. By this time, though, there was no political appetite for action against the press and the Press Complaints Commission was allowed to carry on.