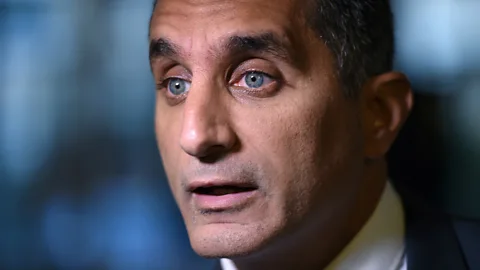

Bassem Youssef: The wild story of ‘Egypt’s Jon Stewart’ (original) (raw)

Getty

Getty

He hosted a Daily Show knock-off during the Arab Spring – and had to flee. Now Bassem Youssef is trying to make it on the US comedy scene, writes Sharif Paget.

Bassem Youssef, a comedian known as the “Egyptian Jon Stewart”, had only enough time to throw a few clothes in a couple of bags. On his way to Cairo airport, he kept refreshing his Twitter feed. As long as his name wasn’t on a no-fly list, he might still have time to escape.

His story mirrors that of the Arab Spring in Egypt itself

Egyptian authorities forced Youssef to flee in 2014 because of jokes he told about the government on his satirical weekly TV show. Now he lives in Los Angeles, where he hopes his comedy career will get a second act, thanks to a new documentary about him, stand-up appearances and a network sitcom pilot.

Youssef’s own story mirrors that of the Arab Spring in Egypt. His meteoric rise began on the internet, gripped a nation and provided hope for democracy, only to be sidelined by the military government. Now, as he reinvents himself for Western audiences, some Egyptians wonder what has become of their revolutionary satirist.

Getty

Getty

Bassem Youssef started his YouTube programme, The B+ Show, named after his blood type, in the early days of the Arab Spring (Credit: Getty)

In 2011, when the Arab Spring swept through Egypt, millions of people took to the streets and demanded the overthrow of Hosni Mubarak, who had ruled for almost 30 years.

Youssef, until then a respected but little-known heart surgeon, went to Tahrir Square, where he helped treat wounded protestors. Despite state propaganda, which blamed the protests on foreign operatives, the demonstrators prevailed, the popular sentiment supported change and Mubarak resigned as president 18 days after the peaceful revolution began.

If you didn’t want protestors don’t tell them they’d get money and Kentucky Fried Chicken – Youssef

Frustrated with the state media portrayal of protestors during the uprising, Youssef began recording short satirical YouTube videos from his laundry room to ridicule government propaganda. He showed snippets of state news broadcasts to which he added satirical commentary. In one snippet, a government talking head said protestors were being offered money and Kentucky Fried Chicken to protest. Then Youssef came onscreen and said: “If you didn’t want people to go to the square, don’t tell them they would’ve gotten money and Kentucky Fried Chicken!”

The revolution was televised

Youssef hoped he’d get thousands of views, but within several months, he had over five million views. A small liberal Egyptian TV network gave Youssef his own programme, Al-Bernameg (The Show), which continued to parody news reporters as well as Egyptian celebrities and politicians.

Getty

Getty

In three months, Youssef’s episodes of The B+ Show had five million views, which led to him hosting Al-Bernameg (Credit: Getty)

After a single season, the show was picked up by a larger network with deeper pockets, and Youssef’s ratings soared. At the height of its popularity, his comedy was being seen by 30 million viewers a week, roughly a third of the Egyptian population.

Youssef’s brand of comedy was groundbreaking. Egypt has a rich history when it comes to social satire – this comedic tradition is essentially that people just make fun of themselves. His comedy marked the first time that satire had been publically directed at government authority.

“The red line during the Mubarak era, whether in print or broadcast media, was criticism or satire of the standing head of state. After January 2011, that line evaporated,” suggests Joel Gordon, University of Arkansas history professor who has been travelling to and writing about Egypt since the early 1980s. “Suddenly, there was this opportunity to poke fun at standing leaders and that’s the real change.”

Getty

Getty

Al-Bernameg was a sensation, watched by 30 million people in Egypt, a third of the population – by contrast The Daily Show averages 1.4 million viewers (Credit: Getty)

With so many viewers watching, Youssef managed to upset both governments that succeeded Mubarak: first the Islamist leader Mohammed Morsi, and then the military government led by General Abdul Fattah al-Sisi. Under the Islamists, Youssef was arrested for insulting the president and Islam, but he thought he might stay in Egypt and fight the charges – that is, until Morsi’s Islamist government was deposed in a military coup in 2013. Egypt moved toward more militaristic, hardline rule under General al-Sisi. The signal for his show was jammed twice and his life was threatened.

You need to leave now – Youssef’s lawyers

“The military has 60 years of experience,” Youssef told me in a recent interview in the US. “The difference between the military and the Muslim Brotherhood is that one tried to stop my show and eliminate me, and couldn’t; and one tried and succeeded because of experience.”

Youssef’s lawyers told him: “You need to leave now.” That’s when he raced to the airport and made his way first to Dubai and then the US. Today, Youssef lives with his wife and two young children in Los Angeles, where he’s starting a new American comedy career.

Getty

Getty

Youssef ultimately fled Egypt, but not before he’d made a major impact – even included on Time magazine’s list of the 100 most influential people in the world (Credit: Getty)

“If you want to be in the field, you need to go where business is, which is either Los Angeles or New York, and Los Angeles is a much better city for kids,” he says.

In 2017, Youssef published a book, took his one-man show on tour, and struck a deal with ABC to develop a sitcom about a Middle Eastern US family with superpowers. “Larry Wilmore and I just signed a deal with ABC to write a pilot for a comedy for next season,” he says.

Lost in translation?

The documentary Tickling Giants, which shows Youssef’s meteoric rise and sudden fall, was recently released. The film garnered support from prominent comedians such as John Oliver and Ed Helms, who moderated Q&As at special screenings in Los Angeles. Sara Taksler, who directed the film, said it’s natural for comedians everywhere to support Youssef. “They understand how important it is to be allowed to tell jokes and not have your life threatened,” she said. “There is a lot of respect for Bassem and what he’s been through.”

Getty

Getty

Jon Stewart appeared on Al-Bernameg before the show ended – and since then Youssef has appeared several times on The Daily Show, including with Trevor Noah (Credit: Getty)

“What he wound up doing was something that I take for granted every day,” Helms, a comedian known for his work in The Office and The Hangover trilogy, said in a telephone interview. “Bassem walked out in the streets into roiling protests and threats to his life and threats to family and friends, and I do this thing that I do so cavalierly, which for him is such an act of courage.”

Youssef’s career has benefitted from the presidency of Donald Trump because of his praise for dictators. People want to hear what Youssef has to say, since he can speak to what it’s really like to do comedy under a strongman. On her popular programme Full Frontal with Samantha Bee, comedian Samantha Bee asked Youssef if he feels better positioned to endure the Trump presidency because of his experiences. Youssef answered, “If Trump was running for president in the Middle East, he would be classified as a tree-hugging liberal.”

Getty

Getty

Youssef has been slowly building his comedy career in the US – speaking at events like the Women in the World conference and hosting the International Emmys (Credit: Getty)

Youssef is also trying his hand at a quintessentially American art form: stand-up comedy. The foray can prove to be especially challenging, since so much of comedy relies on a common cultural understanding between comedian and audience. Youssef had those touchstones in Egypt, especially in joking about the government. In the US, his evolving act focuses on immigration, refugees, terrorism and what it’s like to be an Arab in America.

“I’m not going to speak about specifics about politics because half of the crowd was white Americans and I need to relate to them – I cannot just relate to my own people,” Youssef said backstage after a recent stand-up performance in Boston. Youssef’s comedy has also taken a lighter tone. Instead of Egyptian politics, he’s making jokes about subjects such as first lady Melania Trump. “Last year New York paid $180m to protect an immigrant woman from the president, now she moved to the White House and she’s fine,” Youssef told the audience in Boston.

Some Egyptians in the audience for his US performances are disappointed in Youssef’s new material. They feel as if he’s turned his back on them and the spirit of the revolution in an attempt to become an American celebrity. Amr Alfiky, 28, is a medical student-turned-photojournalist in New York City, who left Egypt after joining the revolution at the same time Youssef became a comedian. Alfiky says Youssef’s comedy used to be “original, genuine and constructive... He was more of an activist”. Now, however, “he doesn’t speak to the revolution. He speaks for Bassem Youssef and his Western audience. He ignored his audience that made him in the first place”.

If Youssef is nostalgic about his career in Egypt, he does not hint at it at all. “I don’t look back,” Youssef said. “I focus on becoming successful here instead of reminiscing about what happened.”

Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Capital and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.