The Japanese magazine shaking up the cosy media club (original) (raw)

Image source, Shukan Bunshun

Image source, Shukan Bunshun

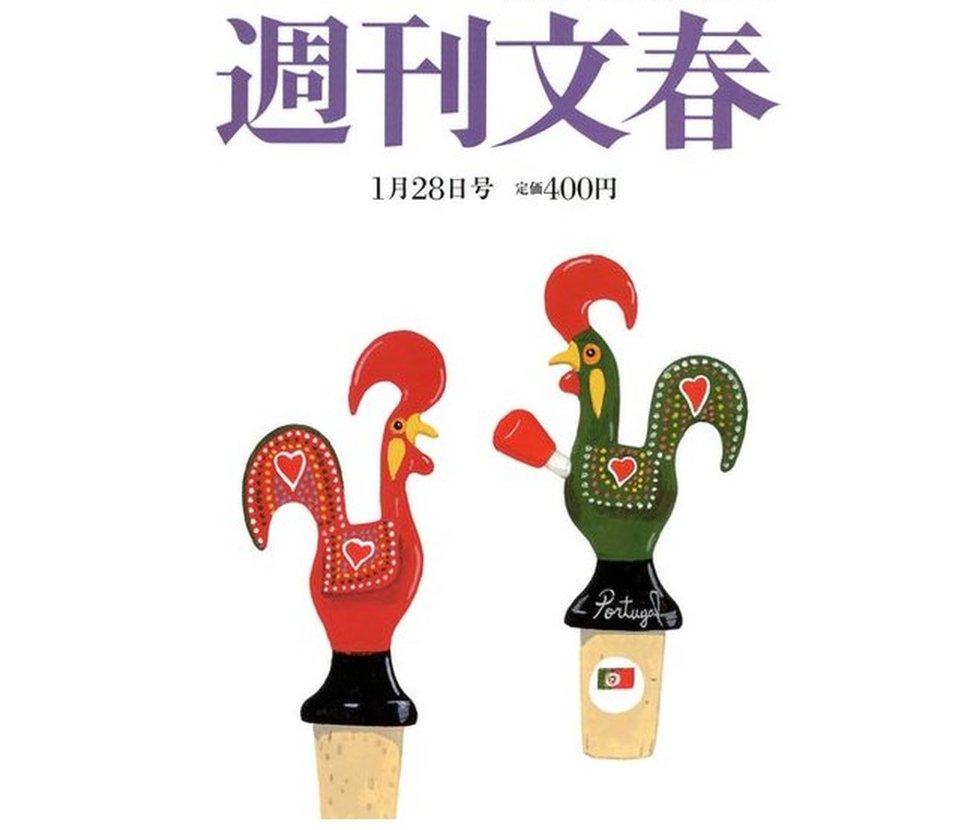

Image caption,

The weekly Shukan Bunshun magazine is known for its big news scoops

As a media organisation getting one scoop can be luck, getting two can be a coincidence, but Japan's weekly magazine Shukan Bunshun had six in the first three months of 2016.

It brought down a minister and a politician, practically destroyed the careers of a popular celebrity and a news commentator and nearly broke up one of Japan's biggest boy bands.

Founded in 1959, it is a tabloid and boasts Japan's largest annual circulation of nearly 700,000. It has held this top spot for more than a decade.

"To get the scoop, you need to want to get the scoop," said its editor Manabu Shintani, "but Japanese media - newspapers, TV or radio - they are no longer actively looking for it because it's too risky".

'Culture of fear'

It is a worrying trend in a country which has fallen from 11th to 72nd ranking in the World Press Freedom Index, external in the last six years.

On Tuesday UN rights expert David Kaye wrapped up a visit to Japan by warning of "serious threats" to the independence of the press and a culture of fear among Japanese journalists.

Although Japan has always said freedom of the press is protected, his comments come amid wider concerns about the government's growing influence on mainstream media.

Image source, Getty Images

Image caption,

Weekly magazines are popular in Japan but few go as far as Shukan Bunshun

Three of Japan's news presenters, NHK's Hiroko Kuniya, TV Asahi's Ichiro Furutachi and TBS's Shigetada Kishii, were replaced at the start of the financial year in April. Their contracts were not renewed.

Some claim they were replaced because they asked tough questions and were critical of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe's administration. There is no evidence to back this, but Mr Kaye's visit to Japan came in the wake of these controversies.

In a recently published essay, external, Ms Kuniya said "I feel that there is growing pressure to conform," adding that mass media is also complicit.

The relationship between the chiefs of major TV stations and newspapers are closely scrutinised by the public, mostly online, with some observers asking if they are censoring themselves to please the authorities. Some accuse the media of "colluding" with the government, or being "under its thumb".

Image source, Getty Images

Image caption,

"When the government says 'right,' we can't say 'left,'" said NHK Director-General Katsuo Momii, a government appointee

Communications minister Sanae Takaichi recently said that the government could revoke a broadcaster's license if it repeatedly fails to show political impartiality in its coverage.

The ministry denies this was a veiled attempt at censorship, but the fear is that journalists stick to what Shukan Bunshun's Mr Shintani calls "safe news", such as the government's official announcements.

There is also a financial reality that many media organisations face.

"Getting a scoop takes time and costs money but not all of them become an actual article," Mr Shintani explained.

For example, it took his magazine nearly a year to publish an article about the bribery allegations against the then Economy Minister Akira Amari who later resigned from his position. Mr Amari said he had received money which he wanted declared as a political donation - however, he said some of it had been mishandled by his staff.

There is also a risk of being sued for defamation. The magazine has been taken to court numerous times and it was once ordered to pay 4.4 million yen ($38,760; £27,350).

Image source, AP

Image caption,

The magazine exposed the extramarital affair of well-known MP Kensuke Miyazaki

But that has not stopped its 40 journalists from breaking stories. The weekly's investigative skills have long been reputable despite the populist nature of some of its reports.

Others have struck very much at the heart of Japan's political culture.

Back in 1974, it was the monthly magazine Bungei Shunju which reported the bribery allegation of the then prime minister Kakuei Tanaka. It eventually led to his arrest in 1976 and Mr Tanaka was later found guilty for violations of foreign exchange control laws.

Biggest scalps

Image source, Courtesy of Fuji TV

Image caption,

The magazine's piece on SMAP nearly broke up the beloved pop group

- Celebrity Becky: her alleged affair with a married singer has resulted in cancellations of all of her regular TV programmes

- Boy band SMAP: the magazine's exclusive interview with Mary Kitagawa, vice president of the powerful talent management agency Johnny & Associates nearly broke up the group

- AKB48 star Minami Minegishi: Shukan Bunshun reported about her spending a night with her boyfriend which broke her management firm's rule, resulting in her infamous apology in shaven head

- Popular musician Aska: he was exposed of his drug use which led to his arrest and a suspended three-year prison term for possession and use of stimulants

- Baseball star Kazuhiro Kiyohara: he was exposed of his drug use which he admitted upon arrest before being released on bail

- "Paternity leave" MP Kensuke Miyazaki: his extramarital affair a week before his wife gave birth resulted in his resignation

- News commentator "Sean K" Sean McArdle Kawakami: the magazine exposed his fake academic background, including a claimed MBA from Harvard Business School, which he said was a past mistake and cancelled all his regular programmes

Their repeated scoops have raised speculation that the magazine hires a private detective which Mr Shintani flatly denies.

"We may pay 5,000 to 10,000 yen ($46-92; £32-64) depending on tips but not much more," he said.

Shukan Bunshun has been winning the scoop battle this year but its rival Shukan Shincho also recently exposed an extramarital affair of Hirotada Ototake, known for publishing a popular book about being born without arms or legs, who had been rumoured to run for parliament.

Image source, AFP

Image caption,

Mr Ototake's book "No One's Perfect" was an instant bestseller in Japan and propelled him to national fame

The story shocked readers, not only because he is a symbol for the disabled in Japan, but also because he has admitted to five affairs.

Some of the so-called scoops have been dismissed as little more than tasteless gossip, but the fact remains the majority of recent exclusives have been broken by such magazines, not newspapers or broadcasters.

So what explains the tabloids getting there first? The finger is often pointed at the journalist clubs which reporters for mainstream media must belong to.

They give them access to government officials and press conferences but foreign media - including the BBC - and freelance journalists are not granted entry, leading to accusations that the authorities are trying to control the information that is reported.

Weekly magazine journalists don't have access either so while they are handicapped in terms of access, they are also freer to write what they like.

"There are lots of debates about how the government is trying to influence media," said editor of Shukan Bunshun, Manabu Shintani.

"But instead of expressing our opinions about it, it is our job to stick to facts and reveal what politicians are up to."

So by mixing big scoops with lots of gossip and pictures of topless girls - similar to that of The Sun's Page 3 girls - the Japanese public gets a different viewpoint and sometimes the real story from a tabloid.