The Mother of Us All – Black Gate (original) (raw)

By Ryan Harvey

Copyright 2007 by New Epoch Press. All rights reserved.

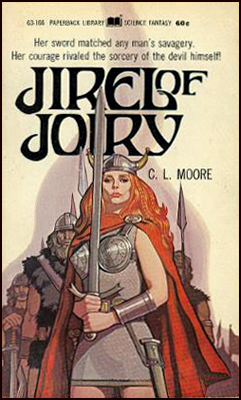

In the influential anthology Sword and Sorceress (DAW 1984), editor Marion Zimmer Bradley dedicated the collection of fantasy with female heroes to C. L. Moore, “who gave us Jirel of Joiry, the first woman to take up her sword against sorcery. And to all of us who grew up wanting to be Jirel.”

In the influential anthology Sword and Sorceress (DAW 1984), editor Marion Zimmer Bradley dedicated the collection of fantasy with female heroes to C. L. Moore, “who gave us Jirel of Joiry, the first woman to take up her sword against sorcery. And to all of us who grew up wanting to be Jirel.”

The red-haired, yellow-eyed, and lioness-fierce sword-wielding Jirel has an unassailable place in contemporary popular culture, along with her genre cousins, the laser-gun wielding heroine and the wooden-stake-armed heroine. Fantasy, science fiction, and horror no longer have “Males Only” signs over their doors, either for their warriors or writers. So many female authors and protagonists thrive in speculative fiction today that it seems hard to imagine a time when the opposite was the case. It feels impossible to visualize fantasy before Catherine Lucille Moore broke down the gender barriers (even if she did partially disguise her sex behind her first initials, C. L.) and brought with her Jirel. Beautiful, fierce, loyal, defiant, passionate Jirel did more than raise her sword against sorcery. She slashed through the confining walls around speculative fiction and let it reach toward the horizons in a way it never could have before her advent. That achievement alone assures Jirel and her creator a place in the firmament of the stars of fantasy literature.

However, the red-haired warrior woman of Joiry means more to the literature of the fantastic than as a progenitor and originator. Alexander Graham Bell patented the telephone, but he wasn’t close to developing cellular phone technology. Thomas Edison invented the light bulb, but he couldn’t illuminate Las Vegas with it. Horror film director Herschell Gordon Lewis, in reference to one of his own movies, said it “was like Walt Whitman poetry — no damn good, but it was the first of its kind.”

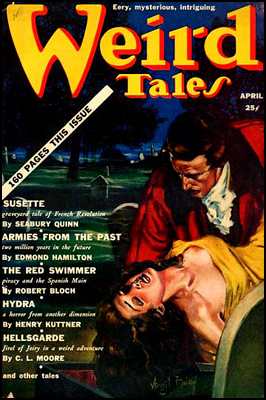

Yet Jirel was the first of her kind, and from the moment she appeared she was already cell phone technology, the lights of the Vegas Strip, and damn good. More than sixty years after she first debuted in the pages of Weird Tales, she stills makes most contemporary fantasy heroines look like pale carbon copies.

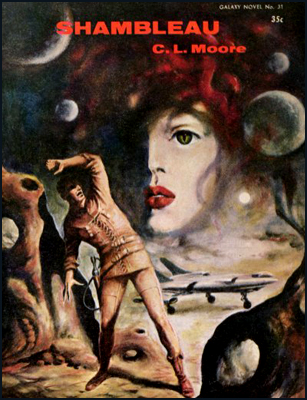

Part of Jirel’s continuing effectiveness stems from the immense writing talent of C. L. Moore. Moore made her publishing debut in Weird Tales in November 1933 with the oddly titled story “Shambleau.” At the time, Catherine Moore was twenty-two years old and working as a secretary at a bank in Indianapolis; she had worked at writing for fifteen years, starting during her sickly childhood, but she never submitted anything until “Shambleau.” The story hurled itself out of Weird Tales editor Farnsworth Wright’s slush pile and literally demanded publication. Superficially a space opera about a rouge of the star ways named Northwest Smith who has a run-in with a deadly alien that may have inspired the myth of Medusa, “Shambleau” contains a dark mood and emotional atmosphere that was rare in science fiction of the day. Moore knew how to write an exciting story, but she delivered her tales with something more than just thrills: she served up a baroque portrait of human nature, illuminated in prose that could make readers almost drop the magazine in astonishment.

Part of Jirel’s continuing effectiveness stems from the immense writing talent of C. L. Moore. Moore made her publishing debut in Weird Tales in November 1933 with the oddly titled story “Shambleau.” At the time, Catherine Moore was twenty-two years old and working as a secretary at a bank in Indianapolis; she had worked at writing for fifteen years, starting during her sickly childhood, but she never submitted anything until “Shambleau.” The story hurled itself out of Weird Tales editor Farnsworth Wright’s slush pile and literally demanded publication. Superficially a space opera about a rouge of the star ways named Northwest Smith who has a run-in with a deadly alien that may have inspired the myth of Medusa, “Shambleau” contains a dark mood and emotional atmosphere that was rare in science fiction of the day. Moore knew how to write an exciting story, but she delivered her tales with something more than just thrills: she served up a baroque portrait of human nature, illuminated in prose that could make readers almost drop the magazine in astonishment.

Less than a year after “Shambleau,” Jirel appeared in Weird Tales. Although Moore wrote more stories about space outlaw Northwest Smith, a character in whom we can see the origins of heroes like Han Solo, Jirel stands as her most significant achievement. The stories about her contain the best synthesis of Moore’s talents during her solo-career years of the 1930s. (Her 1940 marriage to fellow writer Henry Kuttner, also a member of the Weird Tales bullpen, fused the two of them into a conglomerate author, usually known as “Lewis Padgett,” who melded the talents of both.) Writing about a sword-and-sorcery heroine-the very first-allowed Moore to exercise her emotionally charged writing style to its fullest extent. The mixture of the developing genre of sword-and-sorcery with her poetic and humanistic approach created a unique series of fantasy masterpieces. When we read intelligent, cerebral, and emotional sword-and-sorcery today (the kind its harshest critics claim cannot possibly exist) we are witnessing the legacy of Jirel of Joiry.

Jirel belongs to sword-and-sorcery, but she is not a female Conan, as some people have tried pigeonhole her (people who, I can only assume, never read a word of C. L. Moore in their lives and may have gleaned the name ‘Jirel of Joiry’ from a list of fantasy heroines.) Jirel’s stories do not emphasize deliriously paced sword-swinging action or bloody to-the-death contests with horrific beasts. Even though Moore adored such writers as Robert E. Howard and Edgar Rice Burroughs, she did not write in their style of the swashbuckler or the violent battle epic. The focus in the six stories of Jirel is on the heroine’s emotional willpower instead of her sword skill or muscle-power. The reader does see Jirel in action as a warrior and a fierce leader, but her ultimate success usually depends not on her fighting prowess, but on a combination of her fortitude and emotional receptivity.

Jirel belongs to sword-and-sorcery, but she is not a female Conan, as some people have tried pigeonhole her (people who, I can only assume, never read a word of C. L. Moore in their lives and may have gleaned the name ‘Jirel of Joiry’ from a list of fantasy heroines.) Jirel’s stories do not emphasize deliriously paced sword-swinging action or bloody to-the-death contests with horrific beasts. Even though Moore adored such writers as Robert E. Howard and Edgar Rice Burroughs, she did not write in their style of the swashbuckler or the violent battle epic. The focus in the six stories of Jirel is on the heroine’s emotional willpower instead of her sword skill or muscle-power. The reader does see Jirel in action as a warrior and a fierce leader, but her ultimate success usually depends not on her fighting prowess, but on a combination of her fortitude and emotional receptivity.

This emotional receptivity makes Jirel more distinctly feminine than most heroines. This does not imply a sacrifice of power or strength; it implies a different kind of power than we see in male heroes, and (sadly) the majority of female heroes written today. Too frequently the modern heroine falls into the trap of acting like a male bruiser who just happens to have a sex change-often the fault of lazy male writers who have trouble seeing deeper into the “Amazon warrior” cliché.

C. L. Moore made Jirel a fully developed female character, not a generic woman warrior. Even though an extraordinary woman in any day and age, Jirel contains contradictions that make her a flesh-and-blood person, a type of character we still see too rarely in heroic fantasy. Jirel loves passionately and hates feverishly, and she finds herself sometimes torn between her duty as the feudal lord of Joiry and her deepest and darkest passions. She will let no man force himself on her, but she admits that she knows the ways of casual romance, and-within the bounds of 1930s publishing standards-enjoys sex: “She remembered laughter and singing and gayety…she remembered kisses in the dark, and the hard grip of men’s arms about her body.”

Author and editor Lester Del Rey, in his introduction to The Best of C. L. Moore, describes Jirel as “intensely feminine…a woman equal in battle to any swashbuckling male hero who ever ruled over the knights of ancient valor….[She] was no imperturbable battler, however. She loved and hated, feared desperately to the core of her superstitious heart — and yet dared to take risks that no man has ever faced.” Jirel braves hellish worlds, yet finds herself shedding tears for the denizens of these vile places. She travels willingly into nightmares to aid someone who insulted her in the deepest way imaginable. She practices torture in her role as the mistress of a castle (she even considers herself a ‘connoisseur’ of torture), yet she cannot tolerate to see a man she believes betrayed her suffer from magical torment. Jirel’s heart pulls her two directions at once:

“Can’t you see? Oh, God knows I’m not innocent of the ways of light loving — but to be any man’s fancy, for a night or two, before he snaps my neck or sells me into slavery — and above all, if that man were Guillaume! Can’t you understand?”

Jirel’s world and her adventures are as unique as she. As the Lady of Joiry, a fictional demesne in a France that wavers in time from the Dark Ages to the early Renaissance, Jirel has an aggressive duty to and protectiveness of her vassals and people. She sometimes proudly considers herself ‘Joiry,’ an identification she makes a number of times. She rides in full armor to lead her warriors, and they give her the same ironclad respect they would to a man. But Jirel spends scant time among the affairs of the everyday medieval world. In all but one of the stories, Jirel travels to otherworldly realms and dimensions to face body- and soul-searing horror. Moore’s potent word sorcery spins her heroine into places beyond imagining.

Jirel’s world and her adventures are as unique as she. As the Lady of Joiry, a fictional demesne in a France that wavers in time from the Dark Ages to the early Renaissance, Jirel has an aggressive duty to and protectiveness of her vassals and people. She sometimes proudly considers herself ‘Joiry,’ an identification she makes a number of times. She rides in full armor to lead her warriors, and they give her the same ironclad respect they would to a man. But Jirel spends scant time among the affairs of the everyday medieval world. In all but one of the stories, Jirel travels to otherworldly realms and dimensions to face body- and soul-searing horror. Moore’s potent word sorcery spins her heroine into places beyond imagining.

Moore’s predilection for bizarre realms and simplistic plots does however limit the series. Jirel’s adventures, if read one after the other, show an obvious recycling of a similar story: the warrior woman gets transported to a magical reality and fights her way through it, facing an adversary who plies her emotional frailties. Only the last story, “Hellsgarde,” alters this plot construction. The formula works well in the inventive “Black God’s Kiss” and “Jirel Meets Magic,” but feels worn in “Black God’s Shadow” and “The Dark Land.”

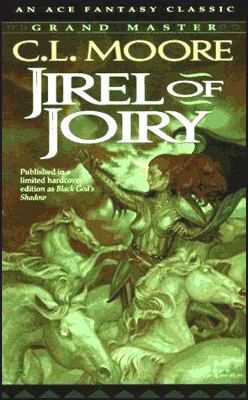

Moore wrote six stories about Jirel between 1934 and 1939. All except for “Quest of the Starstone” have made numerous appearances in anthologies. Together they compose the book Jirel of Joiry (Del Rey) and half of the Fantasy Masterworks volume Black Gods and Scarlet Dreams (Gollancz). After 1939, Moore (in collaboration with her husband Henry Kuttner) turned increasingly toward science fiction. With Kuttner’s death in 1958, her fiction work practically ceased aside from some television writing. She died from Alzheimer’s disease in 1987 after a long period in a coma. She left behind only these six stories of Jirel of Joiry, the mother of female sword-and-sorcery. Somehow, they are enough.

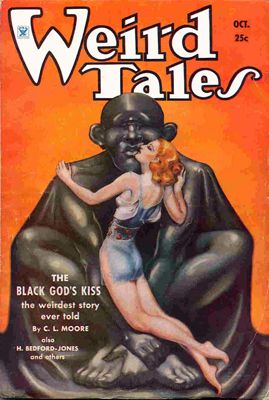

“Black God’s Kiss”

“Black God’s Kiss”

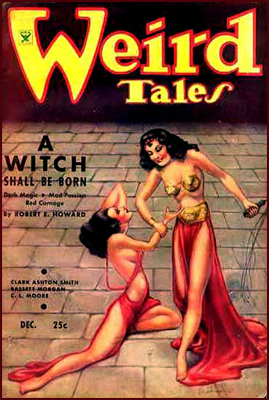

First published in Weird Tales, October 1934.

Jirel made a stunning first appearance on the printed page. Dragged in armor before Guillaume, the darkly handsome conqueror of her fiefdom of Joiry, her helmet is ripped off. Guillaume cannot help but stare…

…as most men stared when they first set eyes upon Jirel of Joiry. She was tall as most men and as savage as the wildest of them, and the fall of Joiry was bitter enough to break her heart as she stood snarling curses up at her tall conqueror. The face above her mail might not have been fair in a woman’s head-dress, but in the steel setting of her armor it had a biting, sword-edge beauty as keen as the flash of blades. The red hair was short upon her high defiant head, and the yellow blaze of her eyes held fury as a crucible holds fire.

Guillaume forces a kiss on Jirel, and sets the stage for the most famous and arguably best story of the series. The thought of the conquest of her beloved fiefdom, combined with the outrage of Guillaume’s lips on hers, sends Jirel on a quest to wreck hideous vengeance on the invader. She escapes from her prison, and with the help of Father Gervase, she descends into the depths of the castle and through a hidden passageway that takes her into a hellish otherworld. Here she hopes to find a weapon to use against Guillaume.

“Black God’s Kiss” establishes the most common motif of the Jirel stories: the heroine enters a deadly and fantastic realm where magic and non-comprehensible science twist reality. Although Jirel and Father Gervase cast the strange realm in religious terms as a kind of hell, it seems merely “different,” and its hostility to humanity nothing more than the result of colliding realities. Jirel’s long slide down a stone tube to reach the under-realm hints that the laws of physical space have shifted. (Subtle hints of logical fantasy and science fiction appear throughout the series). Moore decorates this otherworld with astonishing descriptions that make the supposedly indescribable extremely vivid. Jirel encounters many terrors on her sojourn through this plane: stampedes of cursed blind horses, gibbering rat-like fiends, and a taunting mirror image of herself. Jirel reacts with revulsion to most of it, but another instinct also causes her to shed tears for the land, which feels as if it writhes in pain.

Ultimately, the story has more to do with Jirel’s emotional tangle than with the bizarre land in which she seeks vengeance. The conclusion of Jirel’s quest comes as a startling surprise; but once the shock of the ending passes, it seems apparent that it was the inevitable outcome all along. Moore’s story isn’t only about a heroine’s journey through surrealism; it also tells of a woman untangling the confusion of her emotions while discovering that the consequences of “making a deal with the devil” can mean more than the paltry loss of one’s soul or body. The ending has angered some readers, who have seen Moore’s conclusion as a concession to masculine demands that a woman can only find happiness in surrender to a man. However, the emotional impact of the conclusion goes against this interpretation. Jirel does not surrender: she only discovers, as most people eventually will, that love and hate sometimes walk arm in arm, and wisdom lies in knowing the difference. The most astonishing achievement of “Black God’s Kiss” is that C. L. Moore shows that fantastic and bizarre sword-and-sorcery can exist within the boundaries of all-too-human emotional frailty.

“Black God’s Shadow”

“Black God’s Shadow”

First published in Weird Tales, December 1934.

The success of “Black God’s Kiss” made a sequel inevitable; the follow-up, however, does not achieve the heights of the first since it repeats the same situation with different motives. Jirel descends into the hellish underworld in her castle once more, this time on a quest to rescue, not to destroy. She seeks not only to save the cursed Guillaume, but also to redeem herself from the torment of her actions in “Black God’s Kiss.” She follows the twisted shadow that had once been Guillaume while eluding the crushing force of the black god that gave her the power to destroy her foe in the first place.

“Black God’s Shadow” works best when it deepens the reader’s understanding of Jirel’s emotional fortitude. She pursues a mad, suicidal quest born out of love and guilt. When she repeatedly encounters the black god in its realm, instead of using the sword in her hand to battle it, Jirel overcomes the malign entity through the depth of her feelings of love and kindness. The story also has a fine suspenseful sequence when Jirel tries to slash free from a demonic tree that has captured Guillaume’s spirit and then turns its wrath on her. The conclusion provides a catharsis many readers of “Black God’s Kiss” will welcome, but for all of the story’s many strengths, it remains a ‘shadow’ of its predecessor.

“Jirel Meets Magic”

“Jirel Meets Magic”

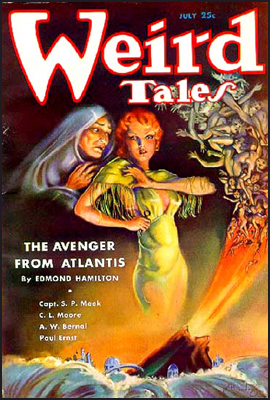

First published in Weird Tales, July 1935.

Jirel again plunges into a magical realm, this time pursuing an escaping warlock, Giraud. The opening shows Jirel in her full-battle glory as she leads her soldiers against Giraud’s fortress of Guichard:

Straight into the massed defenders at the gate she plunged, careering through them by the very impetuosity of her charge, the weight of her mighty warhorse opening up a gap for the men at her heels to widen….Jirel of Joiry was a shouting battle-machine from which Guischard’s men reeled in a bloody confusion as she whirled and slashed and slew in the narrow confines of the gateway, her great stallion’s iron hoofs weapons as potent as her own whistling blade.

No male warrior could receive such fitting praise for ferocity in combat. But Jirel’s real adventure lies not in pitched medieval warfare, but in the magical world of the inhuman sorceress Jarisme.

Moore provides her customary brilliant portraits of weird wonders in a blackly magical world, such as Jarisme’s castle with its myriad doors that open onto strange dimensions and the grotesque alien inhabitants that ooze from them. But the strength of the story — the best after “Black God’s Kiss — derives from Jirel’s confrontation with a female adversary. Jarisme makes a maddening and fascinating opponent; she has Jirel’s power and ambition, but otherwise the two women have nothing in common. If Jirel represents human femininity, than Jarisme represents frozen, empty femininity: beauty, poise, guile, and nothing else. Jarisme’s underestimating of Jirel’s internal female fortitude, something the sorceress cannot comprehend, leads to her downfall. Jarisme declares war on Jirel, promising her torment such that no human could tolerate; but Jirel uses memories of past romantic scars to combat the wizardries. As if to counterbalance this struggle between Jarisme and Jirel, Moore lets her heroine use pure, unbridled hatred to shut down another magical attack. The story begins and ends with the power of hatred and fury, but in the center it praises the might of love against sterility of sensation.

The Fantasy Masterworks edition, Black Gods and Scarlet Dreams, places this story first, preceding “Black God’s Kiss.” This unfortunately dilutes some of its power, since Moore hints that memories of Guillaume aid Jirel in her combat with Jarisme.

“The Dark Land”

“The Dark Land”

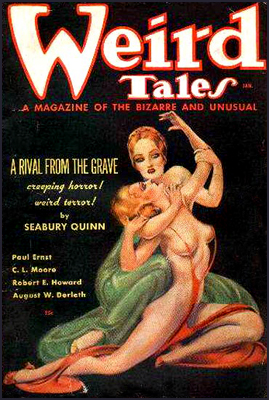

First published in Weird Tales, January 1936.

“You have traveled too often in forbidden lands, Jirel of Joiry, to be ignored by us who live in them,” says Pav of Romne at the beginning of “The Dark Land.” Perhaps Moore had written one too many of these tales about Jirel falling into other dimensions, because “The Dark Land” feels a bit tired and too reminiscent of “Black God’s Kiss.” Pav acts and looks much like Guillaume (according to Moore’s own memories, she devised Pav before she wrote the first Jirel story and he inspired the creation of Guillaume), and again Jirel seeks vengeance for a romantic violation, only to come to regret it.

Pav, the powerful entity who rules the weird world of Romne, snatches Jirel from the edge of death and claims her for his bride. Jirel of course will not have him, and she negotiates a deal: he will allow her to search for a weapon that can slay him, but if she fails she must surrender herself to him. A disgusting creature known as the corpse-witch seems to offer Jirel the weapon she seeks…but the nature of the land of Romne means that Jirel’s revenge could kill her as well.

The land of Romne has the most interesting pseudo-scientific basis of any of Moore’s weird realms. It feels disturbingly limited and enclosed: “…[Jirel] felt the sense of imprisonment in the horizon’s dark, close bounds. It was a curiously narrow land, this Romne. She felt it intuitively, though there was no visible barrier closing her in.” Jirel later discovers that distances in Romne exist mentally, allowing her to move around through line-of-sight. The ultimate explanation of the nature of Romne contains the story’s largest surprise.

Aside from the excellent ending, “The Dark Land” works best during the confrontations between Jirel and Pav. The moment when Jirel threatens to kill herself rather than submit to Pav — and Pav knows she will carry through her threat — is one of the most memorable in the series and captures its heroine’s spirit perfectly. Unfortunately, the story isn’t significantly different from “Black God’s Kiss” or “Jirel Meets Magic” to make it otherwise stand out.

“Quest of the Starstone”

“Quest of the Starstone”

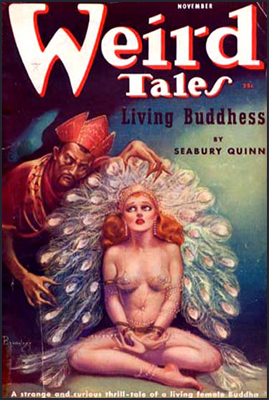

First published in Weird Tales, November 1937.

Moore co-wrote this novelette with her future husband Henry Kuttner. It originated from fan requests to see her two Weird Tales heroes, Jirel and Northwest Smith, encounter each other. It has turned into the ‘lost tale’ of the series, since Moore never felt satisfied with it and it doesn’t appear in any of the Jirel anthologies. It exists apart from the other stories because Jirel isn’t the primary focus and Kuttner’s writing influence appears strongly. Northwest Smith takes the main role, which at least provides the reader a chance to get an outside view of Jirel. But the premise goes only halfway, and Moore’s emotional word magic feels reduced in favor of Kuttner’s more plot-oriented and dialogue-driven writing style.

Bringing together a space opera adventurer and a medieval fantasy warrior requires a serious stretch of the imagination, but Moore and Kuttner smoothly combine the two eras. The warlock Franga, after losing his precious gem the Starstone to Jirel’s attack, traverses time and space to find a man who can defeat her. Naturally he picks Northwest Smith, who sits brooding in a tavern on Mars. Smith and his Venusian sidekick Yarol travel to medieval France and lure Jirel into Franga’s magical realm (yes, Jirel ends up in another eldritch world), but Smith joins Jirel to prevent Franga from taking the Starstone when he sees the repulsiveness of Franga’s world and the strength of Jirel’s defiance.

The story has a more pulpy adventure snap to it than the other Jirel stories (and most of the Northwest Smith stories as well), and the appearance of a comic character like Yarol shows Kuttner’s hand in the writing. Because most of the story comes from Smith’s point-of-view, Jirel’s emotional tumult only appears on the surface, and the conflict between the two of them never gets as heated as it should. However, “Quest of the Starstone” does offer a good deal of classic Weird Tales fun, and in a few places Moore’s dark romanticism peers through: Smith’s morose longing for the Earth when he sits in the tavern and sings the ballad “The Green Hills of Earth”; the description of Franga’s realm, similar to Moore’s other bizarre worlds; and the hint in the stirring final paragraphs of a romance that might have flowered between the two protagonists.

“Quest of the Starstone” has the only specific date reference for Jirel’s time period: 1500, the cusp of the Renaissance. This contradicts the Dark Ages feel of “Black God’s Kiss” and the High Middle Ages weapons like the crossbow mentioned in “Jirel Meets Magic.” There’s no reason to believe that Moore intended the date as canonical.

“Hellsgarde”

“Hellsgarde”

First published in Weird Tales, April 1939.

The last Jirel story is the only one that keeps its heroine entirely in medieval France. Moore mixes Jirel into the classic “old dark house” setting. The lady of Joiry, seeking to ransom her soldiers from her enemy Guy of Garlot, enters the cursed castle of Hellsgarde to find the treasure of its last lord, Andred. Two hundred years past, men attacked the castle to take his fabled but enigmatic treasure; they dismembered Andred, but never found his treasure. Since then, Andred’s dismembered spirit has stalked the castle to protect the treasure, and seekers of it in the abandoned keep do not return alive. However, Jirel finds the castle inhabited; the people there claim they are Andred’s returned descendants, but the warrior woman senses a horrible evil at work.

“Hellsgarde” contains more traditional horror than the other stories, and it also shows Moore’s writing style evolving from her earlier oblique work toward the mainstream nature of her later writing with Kuttner. The story swaps around the ghost and vampire clichés that it seemingly embraces at first, and the ending comes as a genuine surprise. Some of the fright sequences, like Jirel fighting a ghost made of dismembered limbs in pitch-blackness, are brilliantly frightening and show how Moore maintained her visceral power even as she moved toward more familiar genre plots. The story does suffer from the flaw that Jirel doesn’t have much opportunity to advance the story; despite her efforts in the vile castle of Hellsgarde, she ends up more of an observer.

However, the worst flaw of “Hellsgarde” is that C. L. Moore would write no more stories of Jirel of Joiry after it.

Postludium

Postludium

They found me under a cabbage plant in Indianapolis on the 24th of January, 1911, and I was reared on a diet of Greek mythology, Oz books and Edgar Rice Burroughs, so you can see I never had a chance….Nothing used to daunt my infant ambitions. I wrote about cowboys and kings, Robin Hoods and Lancelots and Tarzans thinly disguised under other names. This went on for years and years, until one rainy afternoon in 1931 when I succumbed to a lifelong temptation and bought a magazine called Amazing Stories whose cover portrayed six-armed men in a battle to the death. From that moment on I was a convert. A whole new field of literature opened out before my admiring gaze, and the urge to imitate it was irresistible.

Despite Catherine Lucille Moore’s own account of her education in writing, she never did give into the urge to imitate. Instead, she created. Out of the dreams of childhood and the influence of the other authors whose work she had devoured as a youth, she gave birth to one of the most original of all fantasy characters: the first sword-and-sorcery heroine. And with her, C. L. Moore turned everyone else into imitators.

Jirel of Joiry — the Mother of us all.