Moby on Everything Was Beautiful And Nothing Hurt (original) (raw)

The gospel according to Moby

By Oliver Hurley | October 29, 2022

In 2018, Moby released Everything Was Beautiful, And Nothing Hurt, a return to the soulful electronica of the seminal LP Play. That year, he told us what inspired the record, as well as how he manages to write 300 songs a year…

“Hi Moby. So how’s it going?” “Ah… that’s a really complicated question to answer.”

It’s not the response you’d expect from a multi-million-selling pop star promoting their new album. But then if there’s one thread that runs through Moby’s life and career, it’s that whatever your expectations of him are, he’s likely to confound them.

“Things are great but they’re also terrible, you know what I mean?” he continues and goes on to cite a certain “dim-witted sociopath pushing us towards nuclear apocalypse” as the cause of his malaise. “Apart from that, things are fine.”

The new album in question is the excellent Everything Was Beautiful, And Nothing Hurt (the title is taken from Kurt Vonnegut’s anti-war novel Slaughterhouse-Five).

Inspired by early hip-hop, R&B, and old blues and gospel records, in many ways it harks back to Moby’s monstrously successful album Play.

Lead single Like A Motherless Child is even a reworking of a gospel song dating from the 1870s, mirroring Moby’s use of musicologist Alan Lomax’s crackly field recordings of old spirituals on Play.

Eclectic avenues

The new album also has a woozy trip-hop sensibility, although he demurs from directly citing the genre as an influence.

“Of course, I love a lot of what we think of as the Bristol sound, music starting with Smith & Mighty, Massive Attack and Portishead,” he says.

“But I think more likely Massive Attack and I were influenced by the same late-60s and early-70s R&B. I’m definitely inspired by Bristol trip-hop, but I’m also more specifically being inspired by the same records that they were inspired by.

“I made an album inspiration playlist for Spotify and it has really disparate musicians on it, everybody from Marianne Faithful to Grace Jones, Brook Benton, Liquid Liquid – it really is very eclectic.

“If I had to point to one record that was the biggest inspiration, it’s that one album that Baby Huey made [1971’s _The Baby Huey Story: The Living Legend_].”

While the album feels, thematically, like a continuation of the music that Moby was exploring on Play and its follow-up 18, he says that he’s not intentionally revisiting those records.

“I think it’s just a product of the music that I’ve been listening to. Play was released almost 20 years ago and I think it’s a nice record but I don’t listen to it and don’t give it much thought.”

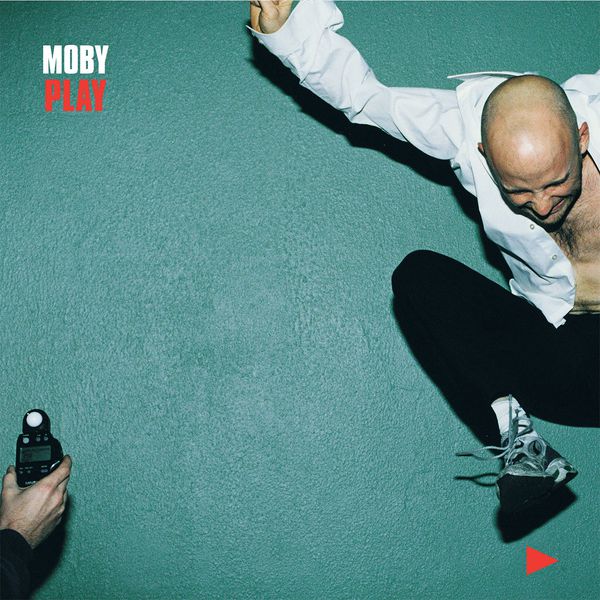

Unsurprisingly, there’s still interest in his landmark LP (if not necessarily from Moby himself), perhaps the most important record ever in terms of bringing electronic music to the masses, and it’s recently been remastered and reissued as a special edition by boutique label Vinyl Me, Please.

“My management company will come to me with ideas about what they want to do, and I just say ‘yes’ because if they think it’s a good idea, I’m happy to go along with it,” says Moby of the reissue. “As long as they leave me alone to work on music in my recording studio, I’m pretty happy.”

Bohemian rhapsody

Moby was born Richard Melville Hall on 11 September 1965 – his nickname stems from the fact that the author of Moby Dick is a distant relative.

His father, Jim, a chemistry professor, died in a drink-driving accident when he was two.

Moby and his mother, Betsy, moved to suburban Connecticut, where she rejected her wealthy background (Moby’s grandfather ran a successful company on Wall Street) and lived a life of intellectual bohemianism that involved, Moby once said, “smoking pot and talking about [German philosopher] Schopenhauer”.

They were, Moby has stated, “very, very poor” and survived on welfare and food stamps. But he was encouraged to write, draw and make music from a young age. Moby joined his first band, hardcore noise purveyors The Vatican Commandos, when he was 17.

- Read more: Making Moby’s Play

In 1989, he moved to New York, where he made a name for himself as a DJ at clubs such as Mars and NASA, while enthusiastically throwing himself into Manhattan’s nightlife.

His own tinkerings with electronic music led to the surprise success of the single Go in 1991 (it reached No.10 in the UK charts).

Following a pair of early compilation albums on the label Instinct that he didn’t want released, his first album proper, Everything is Wrong, came out on Mute in 1995. It embraced techno, gospel, industrial, house and – improbably – speed metal.

Despite lurching between so many styles, it was well received and, as a result, Moby was booked to play that summer’s much-vaunted Lollapalooza tour across the US.

Its follow-up, 1996’s Animal Rights, was a disaster. At the very moment electronic dance music really crossed over (both The Prodigy and The Chemical Brothers were enjoying huge mainstream success during this period), Moby set aside his synths and sequencers in favour of making an album of furious thrash punk.

Confused audiences responded by resolutely not buying the record (it peaked at No.38 in the UK).

When his next album, Play, was released in May 1999, expectations were understandably modest: Mute shifted just 10,000 copies in six months. A year later, it had gone platinum in 17 countries.

Since then, Moby’s output has veered from middle-of-the-road indie rock (Hotel) to rave and hi-NRG (Last Night), with notable detours that take in post-punk (These Systems Are Failing, credited to Moby & The Void Pacific Choir), morose chill-out (Destroyed) and ambient dreamscapes (the four-hour Long Ambients 1: Calm. Sleep).

For anyone wishing to navigate his extensive – not to mention diverse – back catalogue, Moby himself recommends starting with the albums Everything is Wrong, Play and Innocents.

“Of course, there’s a lot that’s not included in that but I feel like someone listening to those three would get a rough sense of the sort of music that I make.”

With his keen sense of melody and ear for a memorable hook, there’s long been a pop sensibility to Moby’s music, whatever the style of any given record. “I think the word ‘pop’ means so many different things to so many different people,” he says, thoughtfully.

- Read more: Moby Reprise interview

“So I understand that you’re speaking in the broadest sense and, yes, to that extent I very much agree. Because I also really appreciate that sensibility in other people’s music, whether it’s Bowie or The Rolling Stones or whomever.

“I like experimental and unconventional music, but there’s something about a strong chorus and a compelling, conventional song structure. It’s what I grew up with and it’s still largely what resonates with me.

“Maybe today people think of pop as Cardi B or whomever but, ultimately, it’s something that’s emotionally engaging and relatively easy to understand without paying too much attention to it.”

Free for all

Moby is less interested today in ‘shifting units’ (if he was ever that concerned about it in the first place) than he is in being given the space to work on music and giving people the chance to hear it.

To that end, he’s released some recent albums for free online, including Long Ambients 1 and a second collection of Void Pacific Choir songs, about which he wrote on his website: “If you want to pay for it, just give money to your favourite charity.”

Then there’s the website mobygratis.com, which features more than 150 tracks available to license for free for independent and non-profit film-makers.

“The nice thing is now people can consume music in so many different ways,” he says. “My record company will get upset with me for saying this, but I don’t really care how people listen to my music. I’m just flattered that they do. So if someone pays for it, that’s nice; if they don’t, I don’t really care.

“Once the music goes out there, I love the weird democratic chaos of how recorded music lives in the world. It’s paradoxically free and not free at the same time and it’s really up to the individual to decide whether they want to own something or not own it.”

Everything Was Beautiful, And Nothing Hurt is Moby’s fourth album in three years. But what he releases is only the tiniest fraction of what he writes. “Because I’m middle-aged and single and sober, I have a lot of free time, so I spend a lot of time working on music.

“On average, every year I write around 300 songs.”

You write 300 songs a year?

“To be clear, that doesn’t say anything about the quality of those songs. So it’s not 300 good songs, it’s just 300 distinct pieces of music. And then over time, I start to figure out which ones are good and which ones are not that good.

“An album, for me, is just a very convenient and hopefully concise way of releasing a body of work. In the past I’ve made records that are very, very eclectic and I think the records I make now are less so. I like that idea of a degree of coherence and a sort of thematic concision, in so far as that’s possible.”

Also aiding in Moby’s quest to carve out the time to compose an average of 25 songs a month is that, for all intents and purposes, he’s given up touring.

In 2017, his lone live performance was at Circle V, a Los Angeles festival promoting animal rights (Moby has been vegan since 1987).

His ‘tour’ for the new album comprises three shows at The Echo in LA and two at Rough Trade in New York. “The reason I don’t tour is simply that I hate it,” he says. “I just don’t like hotel rooms and airports.”

Switching to software

Moby has been making electronic music for three decades. During that time, he considers the way in which it’s created and distributed to be the biggest shift in its development.

“To make electronic music in the 70s, 80s and 90s, and even into the 2000s, involved a studio filled with odd, idiosyncratic pieces of equipment. And at some point in the early 2000s, everything switched over to software,” he says.

“I see it as being really democratic and egalitarian because now, instead of having to go out and buy tons of equipment, any person with a laptop or even a phone can make good-sounding electronic music.

“So there’s no barrier to entry. You can make the music for free, you can distribute it for free and entire massive careers are started this way. It bypasses all the gatekeepers and, as a result, there’s so much music out there.”

Everything Was Beautiful And Nothing Hurt cover

Moby chronicled some of the stories behind his own music with the release in 2016 of his rollicking memoir Porcelain, which covered his time in New York between 1989 and 1999, just before Play came out.

He’s already written the sequel, which addresses both his childhood and the period from the release of Play up until the point at which he gave up drinking – which, in part, inspired his move from New York to Los Angeles.

“I moved to LA seven years ago to be warm in the winter. And also, New York is still a wonderful place but, as is true with a lot of big cities, it’s become almost a victim of its own success.

“It’s become so gentrified, unfortunately creative oddballs can’t really afford to live there any more, and I just found it increasingly a lonely place unless you’re interested in getting drunk every night and involved in the world of finance.”

In writing his latest memoir, Moby says that he tried to learn from other people’s books, “both what they do well and what they do poorly.

“And I feel like when I read other biographies, what I respond to in a positive way is honesty and generosity of narrative – a story that actually engages the reader and is not just weird solipsism on the part of the writer.”

Instead, expect unvarnished and at times unflattering tales of bacchanalian excess (he eventually ended up in therapy for substance abuse).

“It’s so much darker and more debauched than Porcelain, it’s really intense. When I was working on it, my editor kept saying, ‘Are you sure you want to include this? Most people wouldn’t put this in a book.’ Some of that might be taken out but, at present, it’s very, very dark.”

The book may not be released until next year, though. “The world of book publishing, it’s a long process. I’ve finished my part, so now the publishers and I have to have our back-and-forth of legal editing, copy editing and all that.”

- Read more: My Life In Vinyl – Stephen Street

In the meantime, of course, there’s the new album. Like much of Moby’s finest work, there’s a warmth and humanity to it that is at once uplifting and melancholic. It’s his best record in years.

“Making music is just this wonderful practice I get to engage in,” he says. “And then I release it and hopefully it lives in a way that someone can enjoy it or take it into their lives and have a meaningful experience with it.

“I guess the idea with any sort of creative process is you just keep doing it in the hope that maybe you get better and some day you make something great.

“If I don’t make music, that’s a guarantee that I’ll never make anything great. But if I keep working on it, maybe some day, whether it’s tomorrow or in 50 years, I might make something really sublime.”

- Want more from Classic Pop magazine? Get a free digital issue when you sign up to our newsletter!