Abandoned in Guantánamo: Abdul Latif Nasser, Cleared for Release Three Years Ago, But Still Held - Articles (original) (raw)

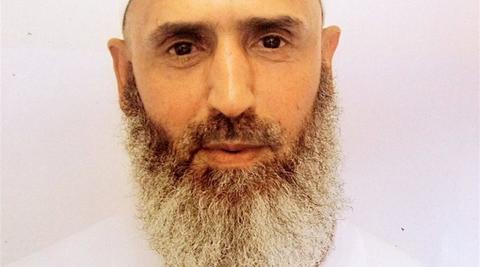

Guantánamo prisoner Abdul Latif Nasser, in a photo taken by representatives of the International Committee of the Red Cross.

If you can, please make a donation to support our work throughout the rest of 2019. If you can become a monthly sustainer, that will be particularly appreciated. Tick the box marked, "Make this a monthly donation," and insert the amount you wish to donate.

By Andy Worthington, August 25, 2019

Over 17 and a half years since the prison at Guantánamo Bay opened, it is, sadly, rare for the mainstream U.S. media — with the bold exception of Carol Rosenberg at the New York Times — to spend any time covering it, even though its continued existence remains a source of profound shame for anyone who cares about U.S. claims that it is a nation founded on the rule of law.

Given the general lack of interest, it was encouraging that, a few weeks ago, ABC News reported on the unforgivable plight of Abdul Latif Nasser, a 54-year old Moroccan prisoner, to mark the third anniversary of his approval for release from the prison. Nasser is one of five of the remaining 40 prisoners who were approved for release by high-level U.S. government review processes under President Obama, but who are still held.

In Nasser’s case, as I reported for Al-Jazeera in June 2017, this was because, although he was approved for release in June 2016 by a Periodic Review Board, a parole-type process that approved 38 prisoners for release from 2013 to 2016, the necessary paperwork from the Moroccan government didn’t reach the Obama administration until 22 days before Obama left office, and legislation passed by Republicans stipulated that Congress had to be informed 30 days before a prisoner was to be released, meaning that, for Nasser, as I described it, "the difference between freedom and continued incarceration was just eight days."

A year ago, Jessica Schulberg revisited his story for the Huffington Post, "telling it in much greater detail than I had been able to, and, I hope, getting it out to a wide audience," as I explained when I cross-posted her article.

As I also explained, Schulberg secured commentary from Nasser’s family, who, to the best of my knowledge, had not been heard from before. As I described it, "His wonderfully supportive family reveal a man who would not pose any threat to the U.S. if released, but then the U.S. authorities already know that, having approved him for release in his PRB for exactly that reason."

For ABC News, Guy Davies also spoke to Nasser’s family, with his brother, Mustafa, explaining how, when he heard the news that the U.S. authorities had cleared his brother for release, "he could barely contain his excitement."

"Within 24 hours," Davies added, "preparations were underway for his return." By Skype, Mustafa told him, "The entire family was relieved and was helping with the preparations. Everyone was doing something. One person prepared the house he would live in, another his room." Davies noted that the family "had even found a potential bride for him to marry upon his return."

Three years later, however, "A series of bureaucratic missteps and political reversals mean that each day Abdul Latif … wakes up in Guantánamo, no closer to freedom." As his brother put it, "the promise was broken."

Guy Davies then rather pointlessly ran through the U.S.’s allegations against Nasser, ignoring the outcome of his PRB, when, as I described it at the time, the board members noted that they had "considered [his] candid responses to the Board’s questions regarding his reasons for going to Afghanistan and activities while there," and "also noted that [he] has multiple avenues for support upon transfer, to include a well-established family with a willingness and ability to provide him with housing, realistic employment opportunities, and economic support."

The board members also noted that they "considered [his] renunciation of violence, that [he] has committed a low number of disciplinary infractions while in detention, [his] efforts to educate himself while at Guantánamo through classes and self-study, and that [he] has had no contact with individuals involved in terrorism-related activities outside of Guantánamo."

Nasser was captured in December 2001 with dozens of other men, crossing from Afghanistan to Pakistan, but as his lawyers at Reprieve explained to Davies, none of the alleged evidence against their client "has ever been presented to a court of law."

Both Reprieve, and Shelby Sullivan-Bennis, who used to work with Reprieve, but is now in private practice, also told Davies that the Northern Alliance sold Nasser for a bounty to the U.S. and that "the testimony of several key witnesses in his case has been discredited," because it was obtained by torture — to which might also be added the fact that one allegedly key witness, who described Nasser as "one of the most important military advisors to UBL [Osama bin Laden]," is a Yemeni who was notorious for telling lies about over 120 of his fellow prisoners.

Abdul Latif Nasser in Guantánamo

Speaking to Guy Davies, Mustafa Nasser explained that, when he "first heard that his brother had been taken to Guantánamo, the news came as 'a shock, beyond shocking.'"

As Davies put it, his relatives were unable to speak to him until 2004, by which time "he had spent two years in solitary confinement," according to Reprieve and his family.

Sullivan-Bennis told Davies that Abdul Latif Nasser’s years in Guantánamo had been "particularly grim," explaining that "he was held in isolation between 2009 and 2011 for 'having influence over other detainees.'"

In conversations at the prison, he told her that, between 2006 and 2007, "he was kept in Oscar Block, where generators 'ran what seemed like 24 hours a day, without cessation, for no discernible purpose other than to make noise.'" As Sullivan-Bennis explained, the generators "caused permanent hearing damage" and "prevented both thought and sleep from reaching the men to any meaningful degree."

In addition, the lights stayed on 24 hours a day. Sullivan-Bennis said that Nasser told her, "Shelby, you cannot imagine," when he spoke of "spending days without sleeping, unable to blot out the light with the thin blankets they were provided [with]."

Nevertheless, as Davies further explained, "Despite these hardships, Abdul Latif has taken the opportunity to immerse himself in Western culture — compiling a list of inspirational quotations from prominent writers among other things," according to his family. A handwritten note obtained by ABC News features a quote from Robert Louis Stevenson: "Keep busy at something. A busy person never has time to be unhappy."

Davies added that, "despite his captivity, it is a philosophy Abdul Latif appears to have lived by," noting that Reprieve explained to him that he "spoke no English when he arrived at Guantánamo in 2002," and yet "he never stopped trying to learn, compiling a 2,000-word Arabic-to-English dictionary," as a result of building up a commanding knowledge of the English language.

Sullivan-Bennis also explained that that Nasser "is specifically one of the most outspoken men in Guantánamo with regard to women getting an education and people being able to express their freedom about religion."

Furthermore, as Davies explained, "she maintains that Abdul Latif was 'never a member of al-Qaida,' and that the state’s version of events is based on evidence that would be inadmissible in a regular, federal court of law." As she put it, "If he had the same rights that I did, he would probably be free."

The malignant role of Donald Trump in Abdul Latif Nasser’s ongoing imprisonment

As Nasser’s lawyers — Shelby Sullivan-Bennis, and Mark Maher, her co-counsel, who is with Reprieve — explained, his continued imprisonment is not just because of what Davies called "a bureaucratic mishap," with the lawyers explaining that "the Moroccan government did not accept the security terms set out by the PRB" until it was too late, but also because of the "pivotal policy reversal" that took place even before Donald Trump became president, when, on January 3, 2017, he tweeted that there "should be no further releases from Gitmo."

As Davies proceeded to explain, "According to an opinion on an emergency motion filed by his lawyers in Washington, D.C. 10 days later, the outgoing secretary of defense, Ash Carter, had left the task of notifying Congress to his successor, Jim Mattis," who had no intention of releasing Nasser.

Six days later, on January 19, District Judge Colleen Kollar-Kotelly rejected the motion, ruling that "[t]he decision to transfer Petitioner pursuant to a recommendation of the PRB rests exclusively within the discretion of the Secretary of Defense," and adding, "Petitioner has no 'right' to such a transfer."

As Davies explained, "The notification to Congress was never issued. Just days from release, Nasir’s freedom had been snatched from him once again."

And under Donald Trump, Guantánamo has become what Shelby Sullivan-Bennis described as "a ghost town." The majority of the remaining prisoners are over the age of 50, and, as she also explained, "A lot of the blocks are actually empty. There are only 24 low value detainees who are kept in any kind of communal living situation."

What hope remains for Nasser is tied to a habeas corpus petition that he submitted with ten other prisoners in January 2018, which I wrote about here, and in which, as Davies noted, lawyers described Trump’s tweet as constituting an illegal U-turn in the government’s approach to Guantánamo, stating, "Given President Donald Trump’s proclamation against releasing any petitioners – driven by executive hubris and raw animus rather than by reason or deliberative national security concerns – these petitioners may never leave Guantánamo alive, absent judicial intervention."

As Davies also noted, "It’s not clear when a judge will rule on the habeas petition, but the last time arguments were heard between the petitioners and the [government’s] lawyers" — in July 2018, as I reported here — "a chilling legal possibility was brought to the fore. The government’s lawyers argued that, under the laws of war, which apply while conflict with the Taliban and al Qaeda are ongoing, the detainees could remain in Guantánamo for the next 100 years."

Nasser — and the four other men approved for release under President Obama — "live in a judicial limbo," as Davies put it, "first promised freedom and then forgotten by an administration determined to keep them detained, without releasing evidence as to why."

Eric Freedman, a professor of constitutional rights at Hofstra University, told ABC News that although the rulings of the Periodic Review Boards "are not legally binding," it is troubling that they have essentially been "frozen" under Trump, and that "administration policy is that no one is to be released, regardless of the evidence." He further explained that federal judges ultimately have oversight over Guantánamo rulings, and that, due to "a torrent of professional criticism," the courts in Washington, D.C. "are beginning to 'assert their proper role' with regards to detainees – which offers some hope for the habeas corpus petitioners awaiting their verdict," and also for Khalid Qassim, a Yemeni who recently won an important case in the court of appeals in Washington, D.C., which I wrote about here.

Mark Maher, Nasser’s co-counsel, told ABC News that Reprieve remained appalled that Trump was waging "an undeclared — and unconstitutional — policy of indefinite detention without trial," noting that "[a]ny one of six U.S. agencies [in the PRB] could have vetoed his transfer, but they agreed unanimously he should be released from Guantánamo."

For Shelby Sullivan-Bennis, the hope is that, "even if Abdul Latif will not be released, more of the evidence used against him will be declassified in order for the defense to attempt to build a stronger case."

Abdul Latif Nasser, meanwhile, wakes up every day in Guantánamo, constantly asking, as he did in a June 2018 meeting with Reprieve lawyers, "Why do I have to stay here?"

The answer, sadly, is that the U.S. has lost all respect for the law since the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, and all decent Americans must wait — like Nasser — to see if judges in the capital will finally take back control of this poisonous narrative, and reassert the important of fairness and the law over innuendo and endless imprisonment without charge or trial.