Stone me, what a legacy: Hancock's Half Hour (original) (raw)

It is hard to officially declare anything as a first, especially in the arts and particularly in the field of British comedy, a place where naturally every great comic is heavily influenced by their predecessors, who in turn were influenced by their predecessors, who had taken to the stage in smoky music halls, long before the advent of television or even radio.

One of the first hit comedies to ever grace the radio waves was Arthur Askey and Richard "Stinker" Murdoch's Band Waggon - a knockabout comedy produced from 1938 until the outbreak of World War II. It was, in its way, the start of sitcom; although, as with all radio comedies of the time, the series broke for musical interludes, emulating the music hall variety shows that audiences of the day were familiar with.

Band Waggon hypothesised that Askey, Murdoch and the rest of the Band Waggon crew were literally broadcasting from atop Broadcasting House, where they had set up a kind of pirate radio station and were even responsible for the pips. The world's first televised sitcom, meanwhile, was a 1946 department store-set series starring James Hayter by the name of Pinwright's Progress (it was broadcast live from the BBC's studios at Alexandra Palace, and as such no recordings were made).

However, if you had to pinpoint the first well-known British sitcom, the one that broke the mould, the one that still holds relevance to this day, it would surely be Hancock's Half Hour. The series burst onto BBC Radio in 1954, introducing the country to 'the lad himself', Anthony Aloysius St John Hancock, who famously lived at 23 Railway Cuttings, East Cheam.

Hancock's situation and career invariably changed depending on the episode, but typically he was portrayed as an out-of-work actor, who had deluded himself that he was more famous than he actually was. He was cantankerous, pompous and comically out of step with the world around him, but most importantly he was endearing and audiences took to him immediately.

Hancock's Half Hour changed comedy forever. Building on what The Goon Show had achieved in revolutionising radio, Hancock's Half Hour was arguably the first series to give a radio comedy series true structure and to let the narrative and characters guide the story.

The writers and creators of the series, Ray Galton and Alan Simpson, alongside Tony Hancock have been described by many (including broadcasting legend and their former agent, Beryl Vertue) as the pioneers of the genre. They strove to tell a story that would, crucially, be uninterrupted by any breaks for music hall variety, popular crooners or sketches - it was quite literally Hancock's half hour. And he, alongside Sid James, Bill Kerr and on occasion Kenneth Williams, Moira Lister, Andrée Melly and Hattie Jacques, took audiences on a journey of fantastical sitcom lunacy.

It was a new world hitherto unknown to audiences, resulting in deserted streets as families would huddle around their radios hooked on Hancock's surreal adventures.

This was the 1950s, where radio was king and television was still just finding its feet - a world almost unimaginable today. They say the past is a different country, and an obvious question that many people who are unfamiliar with Hancock's work may ask, knowing the age of the series: can a sitcom that's over sixty years-old really have relevance to a modern audience? Is the comedy truly timeless? And the answer is 'yes'. Yes, it definitely can.

Tony Hancock was a comic genius. Born in 1924, a young Tony strived to follow in the footsteps of his late father, John (sometimes known as Jack) who himself was a comedian, entertainer and publican who regularly performed to audiences at his establishment, The Railway Hotel.

John's death when Tony was aged just eleven was an event that had a profound effect on him. In 1942, at the age of eighteen, he enlisted in the RAF. He attempted to join ENSA (Entertainments National Service Association), but unfortunately he didn't get past 'Ladies and Gentleman' before becoming paralysed with fear; he just froze to the spot. He tried again a few months later but ended up doing exactly the same thing. It was around this time that his elder brother, Colin, died in action. He was a pilot in the RAF when his plane went missing over the Atlantic.

Tony eventually got a role in an RAF Gang Show, a kind of variety talent review. A member of his troupe, Bill Sutton, remembered him being extremely nervous, but they kept him on because he was fun to be with; everybody liked him.

Although he battled stage fright all his career (and was known to hide his shoes to avoid going on stage), most of the time Hancock found a way through it (largely because his first agent often brought an extra pair of shoes). Entertaining people was his enduring passion, and as soon as the war ended, he became a permanent fixture at the infamous Windmill Theatre in London. Eventually, he worked his way onto Variety Bandbox, a radio series packed with sketches and music, which also launched the careers of Frankie Howerd and Peter Sellers.

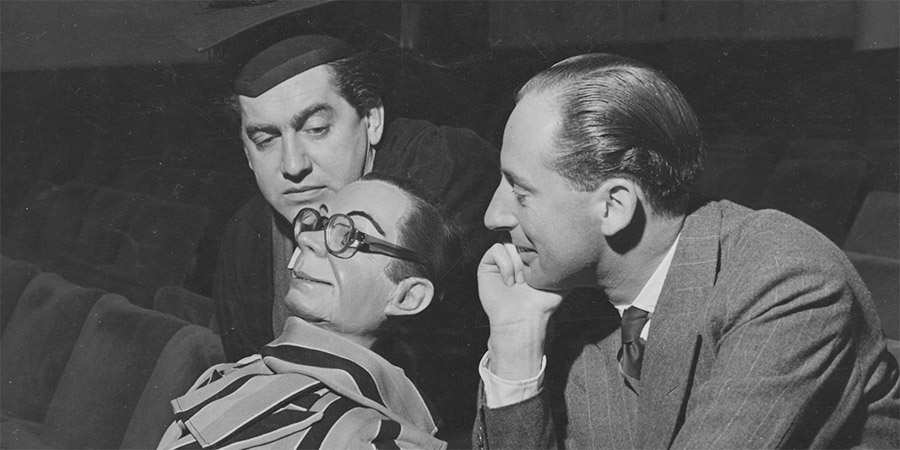

Hancock's first real success was in the popular 1950s radio comedy Educating Archie, which starred ventriloquist Peter Brough and his doll Archie Andrews. It was ventriloquism on the radio (yes, really): Tony played Archie's grumpy tutor, who had grown tired of the puppet's antics, and became a popular feature on the show with his catchphrase "flipping kids!".

Tony was starting to get noticed, but he was yet to pick out the writers who would propel him to stardom. It was while he was working as a minor performer on a TV variety series called Happy Go Lucky that he got chatting to a pair, Ray Galton and Alan Simpson, who had penned a sketch he happened to be performing in. 'Did you write that?' he had asked the two men, at the time only in their early twenties. 'Very funny,' he told them - it was to be the start of everything.

Of the many hours of comedy that the legendary writers Galton & Simpson scripted for him, there were three distinct phases: the initial radio series, Hancock's Half Hour on television, and finally Hancock, which saw Tony go solo with his TV series.

The first, that iconic radio series, running from 1954 to 59 for a phenomenal 103 episodes, always began with those famous low tuba rumblings, while Hancock stepped up to the mic to stutter 'Hhhhhhancock's Half Hour', perhaps in a nod to his nervousness.

He was so gripped by fear that before these recordings he could be found locked in his dressing room dry-heaving. At the start of the second series the pressure saw him disappear altogether. The production team set about searching central London to find him for the night's recording, but Tony Hancock, one of the most famous people in Britain at the time, had inexplicitly vanished.

Police officers, who happened to turn up to be amongst the studio audience felt that he had left the country. So, with no clue as to where Tony was, or when, if ever, he would be back, Hancock's Half Hour went ahead without Hancock. For three weeks Harry Secombe stepped in for his friend, until Tony finally returned. He had fled to Italy; a fact that Galton & Simpson would not learn until many decades later, had actually been known by the BBC all along.

Sadly, none of the episodes featuring Harry Secombe survive, but they were re-recorded in 2017 for The Missing Hancocks with Andy Secombe taking on his father's role. (Kevin McNally otherwise starred as Tony Hancock for these remakes, truly channelling the lad himself in his performance.)

Shortly after his return, the episode, The Chef That Died Of Shame was recorded - an intriguing script that saw a complete departure from the usual format of the series. Billed as a parody of the 1954 film The Country Girl, Tony played a man of great cooking genius who lost everything due to drink.

Despite all of the drama that went on behind the scenes, Tony Hancock never showed any signs of it in his performance, he had the remarkable gift of impeccable comic timing. Sid James remembered: "I think he was absolutely split second perfect. I've never known anyone have timing like he did."

The radio series was, on the whole, much more fantastical than the series that would follow on television, with a much larger ensemble cast. In the beginning it was anarchic and daft (Cinderella Hancock, The Rail Strike); towards the end, more subtle and understated (Hancock In Hospital, Sunday Afternoon At Home); but whatever genre the radio series attempted, it was always tightly scripted, and it always came off.

Listening today, the sheer joy from both cast and audience echoes down the years. According to Hancock's dependable Australian side-kick, Bill Kerr, recordings had to be regularly halted because the cast were laughing so much as Sid James's, Sidney Balmoral James (the middle name a nod to the star's break-out role in The Lavender Hill Mob) twisted Hancock for all he was worth.

Arguably some of the greatest moments of the earlier radio series came when Kenneth Williams arrived in the narrative - he would always play a different role - be it a school governor, car mechanic, or prison inmate - but the essence of the character remained the same: to be as daft and as over the top as possible. He would enter the story at just the right moment, sometimes only brought in during an episode's final act; he was the cherry on the cake, and by the third series, audiences were practically rolling in the aisles when Williams's absurd creation uttered even a single syllable. But although it was radio gold, it was said that playing the straight man to Williams irked Tony somewhat. But was that true?

Tony Hancock had felt that the problem with Williams's character (nicknamed Snide) was that he simply didn't feel real, and after appearing in well over thirty episodes had ended up repetitive; a catchphrase-riddled cliché. This resulted in Williams playing his other characters in some of the later radio episodes (such as Edwardian Fred and the Vicar).

Although Williams left the series much later than the retiring of Snide (after the first recording of the final radio series), the initial disappearance of this most popular of characters poured early fuel on rumours that Hancock insisted on dispatching with cast members.

Famously this culminated in a rather glib joke from Spike Milligan after Hancock's death (which went along the lines of listing various Hancock's Half Hour cast members and stating that he "got rid of them, and then he got rid of himself"). But Alan Simpson (who criticised Spike for his remarks) stated that this simply wasn't true. It seemed merely that Hancock did not like to get stuck in a rut, he wanted to try new things and build new dynamics. He may well have been conscious of the popularity of Williams's ridiculous character, but if so, it did not stop Hancock and his writers bringing Snide over to the television series to great reception from the studio audience.

The character featured in most of the early TV episodes (many of which are unfortunately lost, although one, featuring Williams survives: 1957's The Alpine Holiday).

In a 2016 remake of the lost episode The New Neighbour (starring Kevin McNally and Robin Sebastian) we saw that some of the early editions of the TV series erred towards a Williams/Hancock partnership; yet despite his catchphrases becoming famous ('Stop messing about!', 'Don't be like that!' and 'Oh he don't care, do he?') Williams was ultimately only a relatively small part of the iconic Hancock collective; at its heart, a new and exciting double act was emerging between Tony Hancock and Sid James.

Although the pair always had a camaraderie on radio, the latter series of the TV show paired the two icons in a more intimate house-share setting. At one time they even shared a bedroom and although they didn't quite reach the level of intimacy of Morecambe & Wise's future bed-sharing arrangements, their relationship developed the same inherent sweetness.

For many, this was where the TV series really found its lane. Thinning down the cast from the radio series (which continued to run alongside Hancock's Half Hour on television) had worked. Tony and Sid were the original Odd Couple - a perfect recipe for a double act. The pompousness of Tony delightfully offset Sid's cockney geezer persona and they both shone, bringing out the greatness in each other, both as characters and performers.

There was a beauty to their relationship. This wasn't simply a double act that came on and fired jokes at you. The episode Sid In Love perfectly encapsulates what they had together. Not a lot happens: the pair go to the chippy, Hancock is happy, but Sid is in a mood, so Tony takes it upon himself to sort him out. In one scene the pair sit on a bus together in their iconic garb, whilst Tony points out the billboards he likes along the journey in an effort to cheer Sid up. It's utterly charming. It was always more than just jokes with Hancock: it was all about the characterisation, and finding the humour through these characters. There was always a slightly naïve quality to Galton & Simpson's scripts, and this, in part, is the reason why the shine has never faded from the series.

Hancock's Half Hour pioneered every comedic genre you could imagine, almost effortlessly hitting every mark, but its true deft was introducing intelligent, subtle and surreal humour to the comedy landscape, as we see in the 1959 episode The Set That Failed.

In this episode Sid and Tony become increasingly desperate to watch television, so much so that they casually wander into a peculiar family's house, all of whom are too transfixed by their own set to notice the two interlopers. An extended sequence sees Tony making tea for the family whilst unable to take his eyes off the television, spilling milk and throwing tea leaves around. They perform a surreal dance around each other, never looking directly where they're going or at what they're doing, eyes always fixed on their TV... The whole thing is completely bizarre, but utterly compelling. These were heights of strangeness Monty Python would rarely scale.

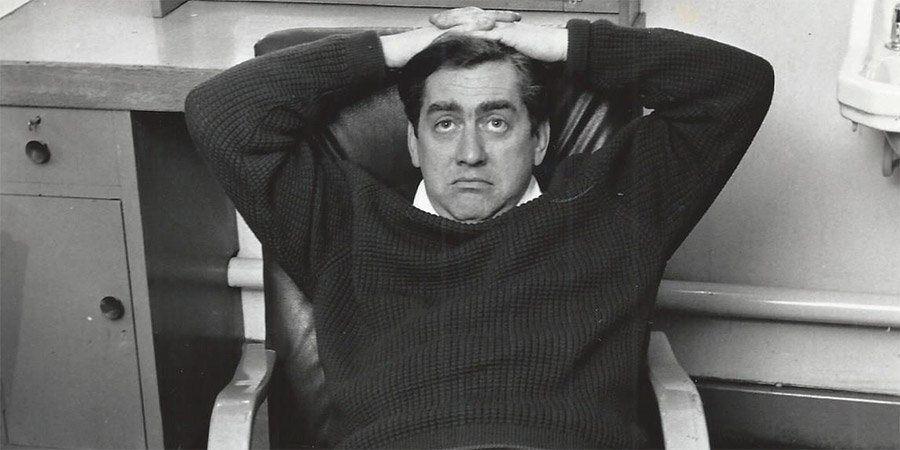

The character of Hancock was unique: whimsical one moment, then sardonic the next. Most of us are familiar with that famous image of Tony Hancock looking morose in front of a cup of tea. It is an iconic photograph but it doesn't really convey the lasting appeal of Hancock's character, which essentially lies within a certain childlike vulnerability that he always managed to convey, even in the character's most arrogant moments.

Hancock is arguably the first in a very long line of self-assured but sympathetic sitcom protagonists, and it seemed that both Tony and Sid were very much the epitome of their on-screen personas.

With Tony in particular, it became increasingly hard to see where the on-screen Tony Hancock ended and the real-life Tony Hancock began, as even he himself once admitted:

"It isn't a character that I play, that I put on and off like a coat. It is greatly a part of me, and a part of everybody else that I see. For instance, I often find that in a script, things that I've said in all seriousness, they later write up in detail and they later turn out to be funny. If I'd been angry or something like that, I look at this and think, yes, that's very funny, unfortunately."

At this time Hancock would rehearse everything obsessively, determined to perfect every nuance of his performance. However, he had never intended to find himself in a double act, it was not how Hancock's Half Hour had begun. Off-screen Sid and Tony were great friends, but Tony found fans increasingly asked him on the street 'Where's Sid?'. He approached the writers regarding going solo, and Galton & Simpson agreed that it was the right call. As with the Kenneth Williams situation, it was a decision that could be viewed in two ways: either Hancock didn't want to share the limelight with James anymore, or once again, felt a desire to try new things and reinvent himself - or perhaps a little of both.

Sid later reflected: "I think he wanted to go it alone, because he was becoming a double act... which makes a lot of sense, there's no question about it, he did do the right thing. I would have liked to have gone on for another series, but only one."

The end of their partnership was something that, to an extent, alienated Hancock from audiences. Sid James was very fond of Tony and they had a real connection, but the die was cast - Galton and Simpson would develop a new sitcom for Sid, Citizen James. (Although not officially a spin-off from Hancock's Half Hour, his character in it is all but identical.)

"I think he really was the greatest friend I ever had," Sid remembered in a 1971 interview. "Very often Tony sort of... seemed to see me like a sort of father figure you know... I mean I'm not that old! But he used to lean on me quite a bit, which suited me because... I felt that I put him at ease a lot. He used to worry about his performance, he'd come and say 'how do you think that was?' I'd say 'marvellous! You can't do any better'."

Sid James's childhood home was on Hancock Street, in Hillbrow, Johannesburg. A daft little coincidence of course, but one that wouldn't have gone unnoticed by Sid. "Hancock's Half Hour was the highlight of his life," Sid James's first wife, Valerie, once revealed. "He loved working with Tony and was never happier. He was devastated when it all came to an end."

Tony insisted that it was purely an artistic decision on his part to let Sid go and that there was no fall out. "There was never any question of the needle between us. Never," he once said.

Alan Simpson also defended Tony's decision: "Sid had a career outside of Hancock's Half Hour. He was one of the leading character actors in the British film industry. One year he made 10 films and he was known in the business as 'One-take James'. He used to get everything right first time and he was the highest paid actor in the British cinema. On one or two occasions he couldn't do the show because he was away filming but, for Tony, Hancock's Half Hour was his career. It wasn't a double act but it was beginning to seem like it. People used to say afterwards it was never the same without Sid but Ray and I would say, 'Hang on a minute, what are the shows you remember most? The Blood Donor? The Radio Ham? Both of them were done without Sid.'"

Tony's final series with his iconic writers the seventh television outing, titled simply Hancock, saw a slight departure from his previous persona. The hat, coat and famous address that defined the old Hancock were gone. The new character was maybe just a tad more daft and less cynical, yet despite these bold changes it is, as Alan Simpson had pointed out, this finale series that perhaps defined Tony Hancock the most.

One of the first episodes Galton & Simpson wrote for it, The Bedsitter, saw Tony entirely on his own. The writers admitted on a few occasions that this may have been a more than slightly pointed decision, but this subtext was lost on Tony, according to Simpson. Hancock was very earnest in his preparation for a unique innovation in comedy - The Bedsitter was the first example of a classic sitcom bottle episode. It was a remarkable feat, and it truly pushed the boundaries of what a sitcom could be.

Striking a tone far more in step with the sitcoms of today. In it we see Tony preparing for a date with childish eagerness, wondering excitedly what he was going to wear that might go with his new girlfriend's leopard skin tights. But, after spending most of the episode getting ready, he was then let down via a simple telephone call. "Leopard skin tights at 'er age! How revolting! I've had a lucky escape," he tries to convince himself with watering eyes. It was perhaps the first time a tinge of genuine sadness had crept into the character.

However, the episode that is remembered best of that final series is of course the penultimate edition, The Blood Donor.

Featuring Tony bumbling into a doctor's surgery making a massive song and dance over the noble sacrifice in which he had chosen to partake, The Blood Donor has become icon in British comedy lore. It is only when he is informed of how much blood is required of him that we hear Hancock's most famous line: "A pint? That's very nearly an armful!"

Galton & Simpson explained how this famous line was developed. First it was:

"A pint? That's an armful!"

Then:

"A pint? That's nearly an armful!"

And finally:

"A pint? That's very nearly an armful."

Making the line more precise had made it funnier; it had made it classic. But why does the addition of two simple words propel it so? It is something that is almost impossible to define - how a slight nuance of performance can change everything. These details were things that Hancock, Galton and Simpson had a very keen eye for; they are the ingredients that make up truly timeless moments in comedy. The little pauses, the minute changes of expression, the modulations of the voice... and Tony had it all.

It may surprise many that when recording this career-defining episode, Tony Hancock was not a well man. He had been involved in a serious car accident earlier in the week, which left him dazed and concussed during rehearsals. With no ability to learn his lines, the recording of the show was almost cancelled. Eventually someone suggested writing his lines on large cue cards - so-called 'idiot boards' - positioned behind the cameras, and make-up was applied liberally to cover his scars and bruises.

It was said that after this event he was never able to learn lines in the same way again, and it is widely accepted that although at the very peak of his career, this marked the start of a sadly quick and terminal decline for the legendary entertainer.

After this final solo series, Hancock wanted to get away from the pressures of weekly television altogether and make films - something that would make him a star in Hollywood - having just completed Galton & Simpson-scripted The Rebel, a surreal masterpiece about a struggling artist. It had been a success in the UK and saw Hancock nominated for a BAFTA, but the film was still considered niche. With his next outing, he hoped to crack America; but he passed up the next script Galton & Simpson wrote for him, The Day Off, as well as multiple other ideas, and penned a feature of his own. It was now ever more apparent that his career was beginning to stall. He had drifted away from the writers that had made him.

In a 2013 BBC documentary where Ben Miller explored the life of Hancock, his own comedy hero, Galton and Simpson informed him that neither party saw their parting as permanent, although the precise nature of their split was not on the most diplomatic of terms. Tony soon moved to ATV with new writers, while Galton and Simpson's renown at the BBC saw them awarded Comedy Playhouse, a format of weekly one-off comedy plays that almost immediately sparked the phenomenal success of Steptoe And Son.

However, whilst the split from Ray and Alan has become legendary, it was not the first time he had broken with the duo, having embarked on a sketch show for ATV, The Tony Hancock Show, which debuted just months before Hancock's Half Hour made the leap to the small screen and ran for two series in 1956/57. Eric Sykes was the primary writer for the series, which also starred June Whitfield, Clive Dunn, Dick Emery and Hattie Jacques. The second series is now wiped, but the first exists and has just been released on DVD for the first time.

Tony's first sitcom for ITV, also titled Hancock, undoubtedly still had some hints of the old magic. The first episode, The Assistant, contains some fantastic scenes, including one where a prudish Hancock, horrified to catch a shop assistant undressing a mannequin in a shop window, attempts to protect its modesty with his coat. However, in doing so, he falls directly through the window, the glass having been removed moments prior - a sight that will instantly remind modern viewers of Del Boy falling through the bar. Yet the series lacked that iconic feel of his BBC work and ultimately the opening titles, which see Tony standing on a traffic island looking lost and directionless, seemed to sum up the entire mood of the sitcom.

People often blame the scripts. However, a lot of the problems that plagued the series stemmed from the fact that the episodes were pre-recorded and then shown to an audience on monitors. No small problem when so much of Hancock's comic genius came from feeding off the live audience. A famous scene from the classic Hancock's Half Hour episode Twelve Angry Men is a perfect example of this.

When Tony takes his role as foreman of the jury and stands up to 'submit' for the first time, we get a speech that on paper wouldn't actually have been that funny. Yet, with every declaration of 'Nay!' it gets more hilarious. 'Surely we must first judge ourselves!' Hancock jabbers, as he hurriedly downs a glass of water, in a bizarre but genius delivery that no one else would have considered. Then he brings the house down with an apparent mistake, saying 'in our own personal wives' instead of 'lives'; he almost breaks into laughter himself before continuing his shouts of 'Nay!', each more charged with the audience's hilarity than the last. No one would ever doubt Galton & Simpson's skills as writers, but when Hancock was on form in front of an audience, he could have performed the phone book and had them rolling in the aisles.

With time Hancock could have elevated this much-derided sitcom, but the truly tragic thing about his ATV effort was that by this time he had lost much of his talent by other means.

Although a genius performer Tony Hancock was also a chronic alcoholic, and declining mental health saw him constantly in and out of rehabilitation clinics. Damaris Hayman, a close friend of Tony's, reflected: "He was the Everest among the peaks of the comedians - very intelligent, but a very sad man. I think now he would be described as bipolar."

Tony battled on with his desire to make the aforementioned second film. Co-written with Philip Oakes, The Punch And Judy Man (1962) saw him put a remarkable amount of his real life on screen. Sylvia Syms, who played his character's wife, explained how she saw the film:

"This was a film which was about his history, the beach... and the Punch and Judy man... it was much more about his life. It's about a man trying to tell you about the awfulness of comedy and how it goes wrong, and how your life goes wrong, and how your marriage goes wrong. It was quite serious themes."

It was also a film that saw Tony put his best friend, John Le Mesurier, front and centre alongside him. Most memorable is a scene in which Tony finds a young boy, who he usually despises for disrupting his Punch and Judy performances, standing bedraggled, having been caught in a terrible downpour on the seafront. Chaperoning him to shelter in an ice cream parlour, Hancock has something of a silent Chaplin-esque stand-off with the ice cream man as he is served a 'Piltdown Glory'. It's a great sequence, but for audiences expecting more of what they saw in The Blood Donor, the downbeat tone of The Punch And Judy Man left them confused.

In 1965 Hancock had been reunited with his former comedy partner when he and James recorded some of their adventures for release on LP in front of a full audience; The Missing Page and, significantly, The Reunion Party.

Hancock's performance was a little shaky, and prior talk of getting back together to make a film had evaporated. A feature length caper starring the duo would have been a dream come true for Hancock fans, but it never came to pass. Sid was said to have vowed never to work with Hancock again and Tony's mental health was continuing to deteriorate rapidly. He was drinking ever more heavily; once meticulously rehearsed, he was now going on stage under-prepared and increasingly confused. A particularly harrowing TV interview from around this time saw Tony Hancock looking vulnerable and devastated as he recalled a moment where he realised things had gone wrong.

"The worst criticism I ever had in my life was from a paper seller. I used to go and pick the papers up from him in the morning and he was always marvellous... He was a great fan you see... and umm, we did one show, and we thought it was a little, well... not bad."

"But not good?" the interviewer interrupts.

"Hmm, fair. You know, and er I went round to him, he was always so enthusiastic about everything all of the time, and he just gave me the papers, and he didn't say anything, he just took the money. Then he looked at me and said 'What happened last night then?'. This is the worst sort of criticism, because I knew then... nobody could have been more for me than him, and if he didn't like it... then things have collapsed."

1967 marked his last television appearance, in Hancock's, an ITV sitcom/variety show hybrid, in which he played the owner of a nightclub. The idea was that extra acts would take the pressure off Tony, but it barely worked. Writer Eric Geen later revealed: "He couldn't learn anything, he couldn't rehearse. He was totally befuddled. There was a doctor there all the time, because when he arrived you didn't know what kind of mood he was going to be in. The doctors were there to give him a pill if he was depressed to buck him up, or another pill if he was bucked up too far to bring him down."

As with other stars that possessed truly timeless talent, such as Judy Garland, or more recently Amy Winehouse, audiences were witnessing a beloved icon fall apart before their very eyes. Comparisons to the rise and fall of Garland are particularly apt. He was a great fan, and on Desert Island Discs recalled seeing her perform his favourite track live, The Man That Got Away from A Star Is Born. To think of these two troubled icons in a room together is quite something, and few could argue that the plot of that film, which saw the male lead lose his professional standing as he battled an addiction to alcohol that culminated in his suicide, could have been any more sadly prophetic for Tony.

It was on the set of that final UK TV series that Hancock met Damaris Hayman, who was often sent to look after him and would frequently read him bedtime stories. She read him many of the classics, but one of the books he especially liked was The House At Pooh Corner.

It was shortly after his last appearance on British television that an ill-fated trip to Australia to film a new television series left Hancock isolated on the other side of the world - and it was there, in 1968 that he took his own life. He was 44.

Frankie Howerd reflected on his passing: "I do not think he died simply because his career had slipped. He was a spiritual man, a good man who was lost in an emotional jungle. He couldn't get out. He was a performer of genius. He lost his judgement of what was the best thing for him to do simply and solely because of the emotional turmoil going on inside him."

Alan Simpson once said of Hancock: "I know it's a cliché but he was Mr Everyman. He was a collection of failings, each of which you would recognise in all your relatives and friends. He was arrogant in a defensive way. He was big-headed, also in a defensive way. He had an inferiority complex. He had all the failings of mankind rolled up in one, and people recognised that.

"We had the best of him. Tony was lovely to work with and a wonderful audience. If something tickled him in the script he just fell about laughing."

While an emotional Sid James once candidly opened up about the last time he saw Tony:

"I'll never forget... I was driving down Piccadilly one day, and I saw Tony standing on a traffic island... and he looked quite dreadful, quite dreadful. I went down Piccadilly and I tried to pull up and get over and see him. He really looked so... miserable and so, oh God I don't know. I keep applying the word 'desperate' to Tony because it was like that. I got the car parked and I pulled up, but by then he had disappeared. I didn't see him again. That's the last time I saw him... He didn't see me. I wish to God I had been able to catch him that day, all sorts of little things can change people's lives."

In his final years, Hancock had a chaotic love affair with Le Mesurier's third wife, Joan, which was dramatized in 2008 as part of BBC Four's Curse Of Comedy season. Hancock's turbulent life has been analysed, perhaps to an excessive degree, in many books and plays: this, Hancock And Joan, starred Ken Stott and Maxine Peake in the lead roles and garnered three BAFTA nominations: best actor for Stott, best actress for Peake, and best single drama.

Becoming a figure of legendary status, Hancock has been portrayed by stars such as Alfred Molina and Richard Briers (Hancock's Last Half Hour) but it was the tragic 2008 film that pulled into sharp focus how a simple miscommunication may have contributed to Tony's untimely death, and was based in part on the book Joan wrote in the 1980s, Lady Don't Fall Backwards, dedicated to both Tony and her husband. Throughout her life, Joan Le Mesurier attended Hancock fan events and always spoke highly of him. She referred to Tony, alongside John, as the great love of her life, and remained committed to keeping both their memories alive until her death in July 2021, aged 90.

Lady Don't Fall Backwards is the name of the mystery crime thriller Tony is reading in the iconic Hancock's Half Hour television episode The Missing Page ... or rather, he had been enjoying it up until he found the last page torn away; that page that revealed the murderer. Naturally, the plot sees him endeavour to get to the bottom of the mystery, with Sid closely in tow. A great scene sees the duo pacing their bedroom and trying to work out whodunnit. Eventually satisfied with their hypothesis, Hancock comes to a sudden realisation when he turns out the light, in a perfect comedic crescendo.

It is episodes like these that really encapsulate how Tony Hancock should be remembered, in his famous black Astrakhan coat and homburg hat, chivvied along by Sid James and his signature cackle.

It's hard to contemplate, or indeed articulate, just how extraordinary it is that these episodes still remain funny and charming, well more than half a century later. When Hancock's Half Hour began in 1954 there were no real iconic British cultural landmarks that we commonly use to define our media heritage today - The Beatles were yet to have their first hit record, there was no Coronation Street, nor Doctor Who on television. Morecambe & Wise had only just embarked on a TV series, but were not yet superstars. There was no Flying Circus, no Two Ronnies.

This was, essentially, the beginning, and ever since, thousands of TV shows, sitcoms and radio series have been the flavour of the moment before dying away, being forgotten and becoming confined to the annals of history. Some simply vanished as they went out live; others were erased, as was the practice of the day (sadly we've lost many Hancock episodes in this way). And lately, many comedies from the past have been subject to scrutiny, series from only fifteen or twenty years ago have been deemed irrevocably dated, and, if we're honest, some are. For a lot of movies or TV series that we attempt to revisit later on in our lives, there's an element of 'You really had to be there' - yet somehow, Hancock's adventures spanning the mid-fifties to very early sixties retain a kind of ageless beauty, standing in the comedy landscape like a great old castle - they seem to exist on a higher plane.

Ray Galton and Alan Simpson once wrote a short piece introducing a Hancock LP that was released shortly after Sid James's untimely death in 1976. They said:

"Tony and Sid are no longer with us, having both gone to meet, as Tony would have put it, the great casting director in the sky. And even though they'll have a lot more competition up there than they ever did down here, if there is any organised entertainment, you can bet your bottom dollar they'll both be topping the bill. In fact, long as these records and tapes exist and are listened to, it's just as if they were still with us. Perhaps that's the truth. They haven't gone, they're just 'resting between engagements' as we so delicately put it in show business. To one age group may [the record] bring on a warm glow of nostalgia and to the younger listeners we hope they will discover a new joy... that of laughing at two of the finest exponents of their art who ever lived."

With an almost Shakespearean level of timelessness to his comedy and tragedy to his personal life, Tony Hancock should be recognised and revered as one of the primary founders of modern British comedy. His legacy lives on, not just in his work, but in every single sitcom you watch on television today. There's something of Hancock that you can feel and recognise in almost every comedian you see, and every comedy you watch. As far as British sitcom goes, it really did all begin here with the legend that is Tony Hancock.

Where to start?

Radio Series 3, Episode 19 - The Conjurer; TV Series 5, Episode 4 - Twelve Angry Men; TV Series 6, Episode 2 - The Missing Page; TV Series 7, Episode 3 - The Radio Ham; and TV Series 7, Episode 5 - The Blood Donor

It is impossible not to immediately recommend The Blood Donor, but that is only the tip of the iceberg as far as brilliant episodes of Hancock's Half Hour (or Hancock) go. The Conjurer offers a great introduction to Hancock's legendary radio series, while The Radio Ham is a TV episode that truly showcases Hancock's ability to carry a farce almost single-handedly.

Twelve Angry Men sees Hancock as the foreman of a jury. It is a stone-cold classic; an early example of parody that is full of extraordinary moments. This is Tony Hancock at the top of his game, he gives us a comedy performance masterclass, as he pleads to his fellow jurors, "Does Magna Carta mean nothing to you? Did she die in vain?"

Finally, The Missing Page has become a classic, now steeped in poignancy; a fan has written a real novel starring the fictional lead, Johnny Oxford, of the book referred to in the episode's title, based on the details that Tony and Sid shared with us of Lady Don't Fall Backwards. And, both Jools Holland and Peter Doherty (a lifelong Hancock fan) independently turned the title into touching ballads in tribute to the comedy star.

Help us publish more great content by becoming a BCG Supporter. You'll be backing our mission to champion, celebrate and promote British comedy in all its forms: past, present and future.

We understand times are tough, but if you believe in the power of laughter we'd be honoured to have you join us. Advertising doesn't cover our costs, so every single donation matters and is put to good use. Thank you.

The Tony Hancock Collection

This collection contains all 37 surviving episodes, from 1956 to 1961, of the classic TV sitcom written by Galton and Simpson, featuring East Cheam's most famous resident, Tony Hancock, alongside supporting stars including Sid James and Kenneth Williams.

Sadly, 17 episodes from the series are missing believed wiped, but their scripts are included in PDF form amongst the set's extras.

First released: Monday 22nd October 2007

Hancock's Half Hour - Complete Series One & Two

Tony Hancock stars with Sid James and Kenneth Williams in the legendary BBC radio comedy series.

Created by Ray Galton and Alan Simpson in 1954, Hancock's Half Hour was the radio vehicle that made Tony Hancock a household name. Each week listeners would be admitted to the sometimes fantastical, sometimes mundane life of "the lad 'imself".

Aided and abetted by Sid James, Andrée Melly, Bill Kerr and Kenneth Williams, Hancock would enter into the spirit of each episode with characteristic dolefulness.

This collection of 15 episodes represents the surviving archive from the first two radio series.

The episodes included are:

Series 1 Episode 1 - The First-Night Party

Series 1 Episode 3 - The Idol

Series 1 Episode 4 - The Boxing Champion

Series 1 Episode 6 - The New Car

Series 1 Episode 10 - Cinderella Hancock

Series 1 Episode 11 - A Trip To France

Series 1 Episode 12 - The Monte Carlo Rally

Series 1 Episode 13 - A House On The Cliff

Series 1 Episode 14 - The Sheikh

Series 1 Episode 16 - The End Of The Series

Series 2 Episode 5 - The Holiday Camp

Series 2 Episode 6 - The Chef That Died Of Shame

Series 2 Episode 8 - The Rail Strike

Series 2 Episode 9 - The Television Set

Series 2 Episode 11 - The Marrow Contest

First released: Thursday 18th September 2014

Hancock's Half Hour - Series Four

Tony Hancock stars with Sid James and Kenneth Williams in the legendary BBC Radio comedy series. Created by Ray Galton and Alan Simpson in 1954, Hancock's Half Hour was the radio vehicle that made Tony Hancock a household name.

Each week listeners would be admitted to the sometimes fantastical, sometimes mundane life of "the lad 'imself". Aided and abetted by Sid James, Andree Melly, Bill Kerr and Kenneth Williams, Hancock would enter into the spirit of each episode with characteristic dolefulness.

This collection of 20 episodes represents the surviving archive from the fourth radio series, along with PDF booklets featuring episode guides, series notes, cast biographies and specially written introductions by Galton and Simpson.

The episodes included are: Back From Holiday, The Bolshoi Ballet, Sid James' Dad, The Income Tax Demand[/i], The New Secretary, Michelangelo 'Ancock, Anna And The King Of Siam, Cyrano De Hancock, The Stolen Petrol, The Expresso Bar, Hancock's Happy Christmas, The Diary, The 13th Of The Series, Almost A Gentleman, The Old School Reunion, The Wild Man Of The Woods, Agricultural 'Ancock, Hancock In The Police, The Emigrant, and The Last Of The McHancocks.

First released: Thursday 3rd September 2015

Hancock's Half Hour - Series Five

The complete fifth series of the legendary BBC Radio comedy series starring Tony Hancock.

This volume contains all 20 episodes from the fifth radio series, collected together for the first time. In these hilarious Half Hours, Hancock has a makeover; turns his home into a private school; stands in the East Cheam by-election; presents three short plays from the East Cheam Repertory Company; takes in a wrestling match with Miss Pugh and gets more than he bargains for when he wins a TV quiz show.

The episodes are: The New Radio Series; The Scandal Magazine; The Male Suffragettes; The Insurance Policy; The Publicity Photograph; The Unexploded Bomb; Hancock's School; Around The World In Eighty Days; The Americans Hit Town; The Election Candidate; Hancock's Car; The East Cheam Drama Festival; The Foreign Legion; Sunday Afternoon At Home; The Grappling Game; The Junk Man; Hancock's War; The Prize Money; The Threatening Letters and The Sleepless Night.

This new set includes improved audio quality and extended edits for five episodes, plus a previously unreleased 'mini-episode' recorded to coincide with the 1958 Commonwealth Games.

First released: Thursday 3rd March 2016

Hancock's Half Hour - Series Six

The complete final series of the ground-breaking BBC Radio comedy starring Tony Hancock - plus five bonus episodes.

This volume contains all 14 shows from the sixth radio series, collected together for the first time, including previously unpublished restored versions of The Waxwork, The Fête and The Poetry Society. Also included is the 1958 Christmas Special episode and four re-recordings made for the BBC Transcription Service.

Among these hilarious _Half Hour_s, Hancock enters an eating competition; sets out to save a local landmark; becomes the director of Sid's guided tours company and enjoys an evening of abstract verse with his avant-garde friends.

The episodes are: Bill And Father Christmas (1958 Christmas Special); The 13th Of The Month (Transcription Services Episode One); The New Secretary (Transcription Services Episode Two); The Ballet Visit (Transcription Services Episode Three); The Election Candidate (Transcription Services Episode Four); The Smugglers; The Childhood Sweetheart; The Last Bus Home; The Picnic; The Gourmet; The Elopement; Fred's Pie Stall; The Waxwork; Sid's Mystery Tours; The Fête; The Poetry Society; Hancock In Hospital; The Christmas Club and The Impersonator.

First released: Thursday 4th August 2016

The Missing Hancocks - The Complete BBC Radio Series

Kevin McNally and Andy Secombe star in new recordings of original Hancock's Half Hour scripts by Ray Galton and Alan Simpson.

Between 1954 and 1959, BBC Radio recorded 102 episodes of the hugely popular comedy classic, Hancock's Half Hour. The first modern sitcom, Hancock's Half Hour made stars of Tony Hancock, Sid James and Kenneth Williams, and launched Ray Galton and Alan Simpson as one of the most successful comedy-writing partnerships in history.

Sadly, 22 episodes of the show were wiped and still do not exist in the BBC archives, so have not been heard since their original transmission nearly 60 years ago - until Radio 4 lovingly recreated them over four highly-acclaimed series between 2014 and 2020. In a special treat for Hancock's Half Hour fans, Series 4 also premiered one episode - The Counterfeiter - that was never recorded by the original team.

Complete with the classic score performed by the BBC Concert Orchestra, these hilarious episodes were recorded at the BBC Radio Theatre in front of a live audience. Kevin McNally stars as The Lad Himself, with Andy Secombe playing the role of his father Harry and a stellar cast including Simon Greenall, Kevin Eldon, Robin Sebastian, Margaret Cabourn-Smith and Susy Kane.

Also featured is a bonus director's commentary for The Matador, in which Andy Hamilton chats to Kevin McNally and co-producer Neil Pearson about the joys, and challenges, of recreating a 1950s sitcom.

First released: Thursday 4th March 2021