Sticky splices and hairy palms (original) (raw)

_Venusvill_e (Fred Worden and Chris Langdon, 1973).

DB here:

Just as CDs gave us a taste for sterile sound, the DVD has made us prize the clean image. We like sleek, hard-edged frames that look good on computer monitors and home-theatre screens. So who would put up with a shot like the one surmounting today’s entry?

Mark Toscano, for one. He’s a film preservationist for the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences Film Archive. Among other tasks, he searches out and preserves experimental and avant-garde cinema, particularly work from West Coast filmmakers. And he savors shots like that hairy palm.

Mark Toscano, for one. He’s a film preservationist for the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences Film Archive. Among other tasks, he searches out and preserves experimental and avant-garde cinema, particularly work from West Coast filmmakers. And he savors shots like that hairy palm.

We normally think that someone preserving a film must at the minimum do a cleanup—remove all the specks, hairs, rips, and bad splices—before going on to more serious fixing, like correcting faded color. But what if the filmmaker left in the dirt and glue blobs deliberately? Or what if the filmmaker developed a fondness for the wear and tear that the movie accumulated over years of use? What’s a dutiful archivist to do?

The virtues of degradation

Mark is aware that archivists can have a big impact on film culture. By selecting films to save, they expand the canon and invite researchers to consider work that might otherwise be missed. “A curator’s enthusiasm can fuel new scholarship.” So part of Mark’s mission is to bring the inventiveness of lesser-known avant-garde filmmakers to new prominence.

Surprisingly, sometimes the archivist has to convince a filmmaker that work is worth saving. Robert Nelson had decided that most of his films were of little interest and in 1999 began redoing some and even destroying others. The scrapes you see on The Awful Backlash (above), a film about a tangled fishing reel, are the result of Nelson’s decision to rub out parts of the soundtrack.

Above all, a preservationist can widen the audience by programming collections like the one Mark brought to our Cinematheque last week. His Friday program was a feast of LA experimental film from the 1960s and 1970s. The menu ranged from gorgeous abstractions like Fred Worden’s Throbs (1972) and Pat O’Neill’s 7362 (1967) to exercises in dry wit like Morgan Fisher’s Turning Over (1975), about the momentous instant when a car’s odometer flips from 99,999 miles to 100,000. There was Kathy Rose’s Mirror People (1974), a sinister exercise in fairy-tale animation, headcomix-style, and Diana Wilson’s charming stop-frame still life Rose for Red (1980). One of the program’s implications was that on the Left Coast, avant-garde films were less cerebral than the official classics of the East Coast establishment. Films like David Wilson’s Stasis (1976) and Gary Beydler’s indescribable Pasadena Freeway Stills (1974) show that Structural Film could offer sheer entertainment. Mark’s notes on several of these titles can be found here.

The day before the screening, Mark gave a talk to our departmental colloquium called “Print (de)Generation.” He was paying ironic homage to our colleague J. J. Murphy’s 1974 classic, Print Generation (which Mark is restoring). But his title captures as well the problems of preserving films that don’t aim at pristine imagery.

If you assume that your job is to find the best existing form of the film and conserve that, what do you do with experimental work? Sometimes the films are designed to look messy. Sometimes they acquire a wear and tear that is like the patina on a sculpture or piece of furniture, when the signs of time’s passing become part of the texture of the piece.

Mark gave many examples of the decisions he faces in preserving the deliberate roughness of some work. Ben VanMeter (in spirit and approach, Mark feels, the most classically hippie West Coast filmmaker) corrugated the film strip of Acid Mantra; or, Rebirth of a Nation (1968). The legendary but little-seen Maltese Cross Movement (1967) by Keewatin Dewdney is a dazzling exercise in process structure, and the speckling on the images comes from creative choices. Shots were intercut with black frames—not black film frames, but frames dabbed with opaque paint. Inevitably, flakes of paint migrated across nearby footage.

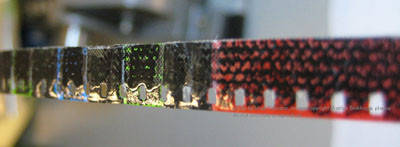

Brakhage’s films call for special delicacy. Mark showed lovely photos of film strips that Brakhage had painted upon, or welded together with thick splices that look like chain mail, as in the fourth reel of 23rd Psalm Branch (1967).

The Garden of Earthly Delights (1981) incorporates bits of grass, ferns, and insect wings.

How do you preserve such a thing? Brakhage endlessly revised some of his work, and came to appreciate the flaws that reprinting shooting and editing introduced into a film. When Mark called him about eradicating a hair that had crept into Flight (1974), Brakhage replied: “That hair is the axis around which the entire film revolves.” [Please see PS at bottom of post.]

Feelthy peectures

Mark’s talk highlighted Chris Langdon, a little-known Cal Arts filmmaker who worked with John Baldessari, Robert Nelson, and Fred Worden. Worden collaborated on Venusville, (1973), a deadpan satire on Structural Film. Shots of a palm tree tremble in front of us, while we hear puzzled comments from offscreen filmmakers. The image gets grubbier as the film proceeds, as if the viewers were looping it in their search for clues.

Langdon’s work vividly displays the West Coast impulse to hold nothing sacred. You would think that the endlessly self-ironizing Warhol was beyond teasing, but Bondage Boy (1973) makes a good try. We see a fellow wrapped in plastic and chains and struggling half-heartedly while assuming some fairly un-erotic postures. The soundtrack is “These Boots Are Made for Walking.” Langdon made fifteen to twenty films per year in a great many styles, and even created trailers for some of them, including Bondage Boy. She also came up with trailers for unmade films, as in Love Hospital Trailer (1975; above).

Mark’s passion and persistence brought Langdon’s films back to notice very recently, at a Redcat retrospective curated by Mark, Steve Anker, and Bérénice Reynaud. “I guess I was just a little incredulous that anyone would remember those films, and a little wary about it, to be honest,” said Langdon, who now prefers to be known as Inga. “But after a while, I thought it was pretty cool.” Scholars will be lining up to write about her work, with its wild humor and ties to Structural and Punk cinema.

You might not expect the Academy to preserve avant-garde cinema, but it’s a great testament to the institution that it cares so much about all kinds of film. Mark generously praised his colleagues Mike Pogorzelski and Joe Lindner (both Wisconsin alums), who support his efforts. In turn, we’re grateful to people like Mark who devote themselves to recovering films in a way that respects filmmakers and their work—especially when that work seems defaced or distressed. He teaches us that imperfections aren’t always faults. Everything in the world spoils eventually. Why shouldn’t artists acknowledge that? No surprise to learn that Mark owns few CDs but hundreds of LPs. He’s a master in bringing the Vinyl Aesthetic to film.

Mark Toscano keeps a blog titled “Preservation Insanity,” with more images of despoiled imagery, here.

Film preservation and restoration have formed a running thread for Kristin and me, from our trips to Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato to our reportage on visits from archivists like Grover Crisp.

Currently there’s a blogathon on preservation sweeping the Internets. You can read about it at the Self-Styled Siren and Ferdy on Film, both of whom are keeping running tally on the entries. Please consider contributing to the National Film Preservation Foundation.

You can read more about the West Coast experimental tradition in David E. James, The Most Typical Avant-Garde: History and Geography of Minor Cinemas in Los Angeles (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005) and Chapter 6 of Paul Arthur’s A Line of Sight: American Avant-Garde Film since 1965 (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2005).

PS 19 February: Marilyn Brakhage posted this correction to the Frameworks listserv (ellipses in the original):

I’m glad to see Mark’s work getting some more, deserved attention. However, after reading the blog (which I can’t seem to respond to directly) just thought I’d mention — for the sake of historical accuracy — that the comment from David Bordwell that “Brakhage endlessly revised some of his work . . . ” is simply not true. When a work was done, it was done, and he moved on. He did not re-make/re-edit old work like some filmmakers do. . . . Perhaps Mr. Bordwell was thinking of the inevitable problems in print variation coming through the labs over the years (that the filmmaker, of necessity, had to adjust to), or the “translations” that resulted from blowing up 8 mm to 16 mm versions for distribution purposes. But I wouldn’t call that “revising” his work. (I’m sure he wanted the “translations” to be as true as possible to the original.) . . . And the hair that had “crept into Flight” was there from the beginning — accepted and used by Stan when he began to edit the film. It wasn’t something that happened over time.

I regret my misunderstanding of Mark’s remarks on the subject, and I’m grateful to Marilyn for setting the record straight.

Robert Nelson’s painted and resin-sealed cans of film. Another approach to preservation? Images courtesy Mark Toscano.

Last Modified: Friday | July 23, 2010 @ 19:04  open printable version

open printable version

This entry was posted on Wednesday | February 17, 2010 at 5:53 pm and is filed under Experimental film, Film archives, Film comments, Film history. Responses are currently closed, but you can trackback from your own site.