The semiconductor shortage and its implication for euro area trade, production and prices (original) (raw)

Prepared by Maria Grazia Attinasi, Roberta De Stefani, Erik Frohm, Vanessa Gunnella, Gerrit Koester, Alexandros Melemenidis and Máté Tóth

Published as part of the ECB Economic Bulletin, Issue 4/2021.

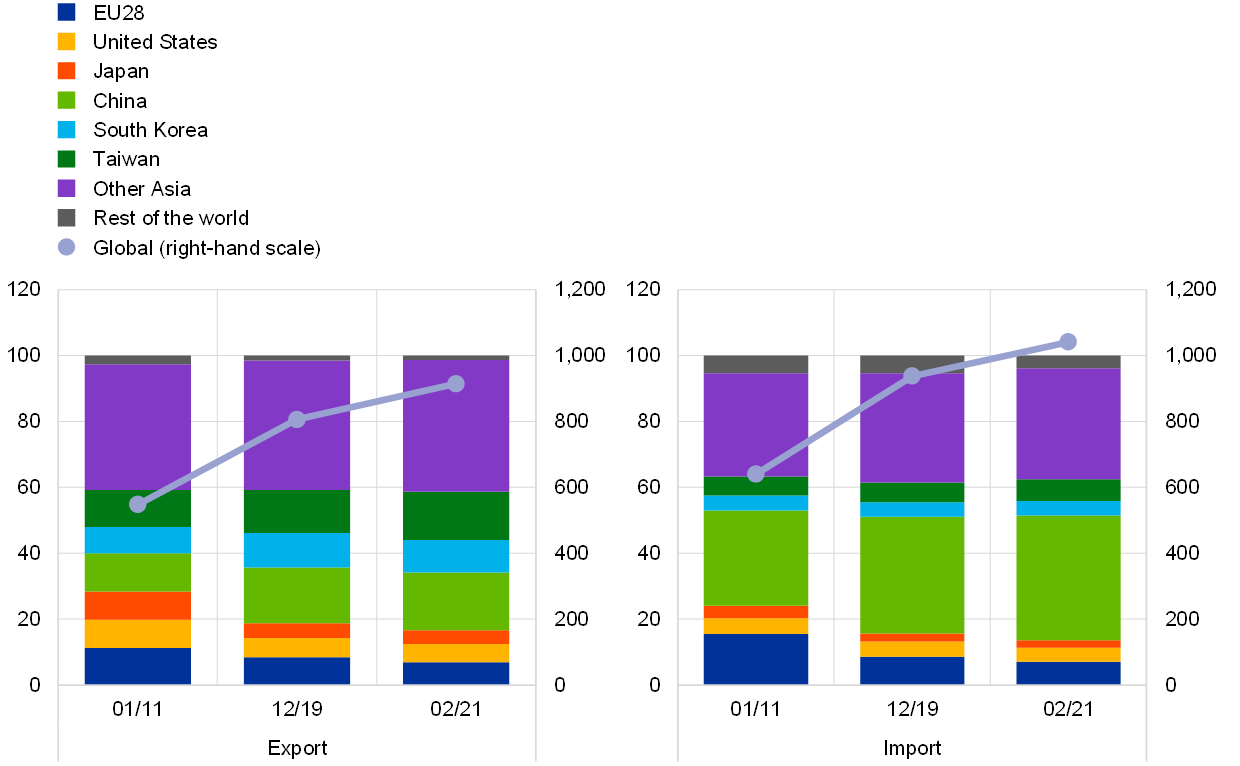

The semiconductor industry has recently seen a strong surge in demand. Revenues from global sales of semiconductors have almost doubled over the past decade and the Asian economies have consolidated their market dominance in this regard (Chart A). Looking at imports, the share of Chinese imports of semiconductors appears to be growing compared to that of the EU and the United States. At the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, while sales of semiconductors to the motor vehicle industry collapsed globally during the second quarter of 2020, this shortfall was more than offset by a strong demand for computer and electronic equipment owing to the shift to remote working and distance learning. Once the global recovery took hold, the production of semiconductors was not sufficient to meet the surge in demand from the motor vehicle industry. In addition, various adverse events, such as fires and droughts affecting large manufacturing plants aggravated the global supply shortage of semiconductors.

Chart A

Global semiconductor trade by region

(left-hand side: percentage share; right-hand side: USD billions)

Sources: Trade Data Monitor and ECB calculations.

Notes: Semiconductor parts under Harmonized System (HS) code 8541 and HS code 8542. Latest observations are for February 2021.

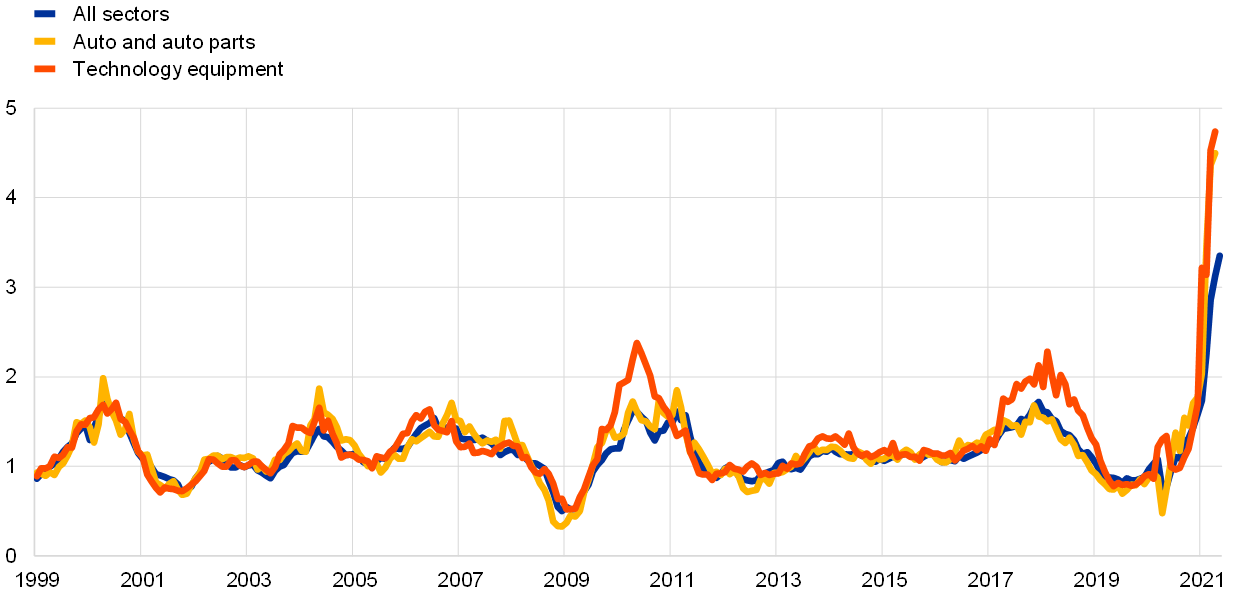

While experiencing a recovery in demand, euro area producers of manufacturing goods struggled to source semiconductors. Since the supply had meanwhile been directed elsewhere, euro area imports of semiconductors decreased substantially following the start of the pandemic despite being more resilient than total imports. However, their growth rates lagged behind that of total imports during the recovery phase (Chart B). Although the share in production of inputs from the IT and electronic sector is not that substantial, this sector is a crucial upstream supplier and any disruptions are therefore likely to extend to many other sectors in the economy. Combined with shortages of other inputs (e.g. chemicals, plastic, metals and wood), and shipping disruptions, the semiconductor chip shortage severely affected suppliers’ delivery times. This resulted in an unprecedented increase in the ratio of PMI new orders to suppliers’ delivery time[1] for manufacturers in the euro area, particularly in industries that use semiconductors for production, such as the auto and auto parts as well as the technology equipment industries (Chart C).

Chart B

Euro area semiconductor imports

(annual percentage changes of three-month moving averages of values)

Sources: Trade Data Monitor and ECB calculations.

Note: Latest observations are for February 2021.

Chart C

Euro area suppliers’ delivery times

(ratio of PMI new orders to suppliers’ delivery times)

Sources: Markit and ECB calculations.

Note: Latest observations are for April 2021 for sectoral PMI and May 2021 for the aggregate PMI.

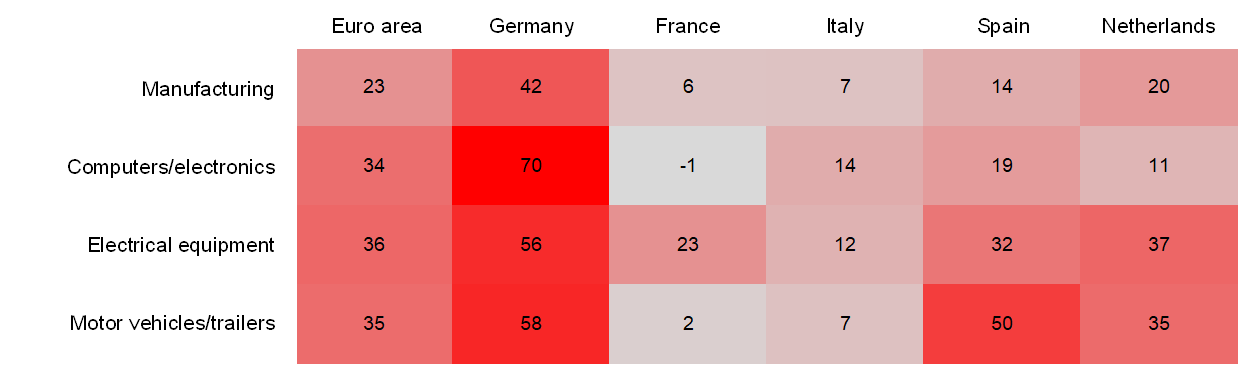

Recent survey evidence points to severe bottlenecks in some of the key manufacturing industries, particularly in Germany. According to the latest quarterly European Commission Business survey, 23% of manufacturing firms in the euro area reported a lack of material and/or equipment as a key factor limiting production (Chart D), which currently stands well above the historical average (around 6%). Chart D shows that the effects of these semiconductor bottlenecks are most visible in industries with a higher input share of electronic equipment, such as in the computer and electronic, electrical equipment and automotive industries. Across countries, this shortage is clearly apparent for German firms.

Chart D

Shortage of material and/or equipment as a factor limiting production

(percentage of survey respondents by industry)

Source: European Commission Business survey, April 2021.

Note: The time series for the survey responses are seasonally adjusted which may explain negative values in some industries.

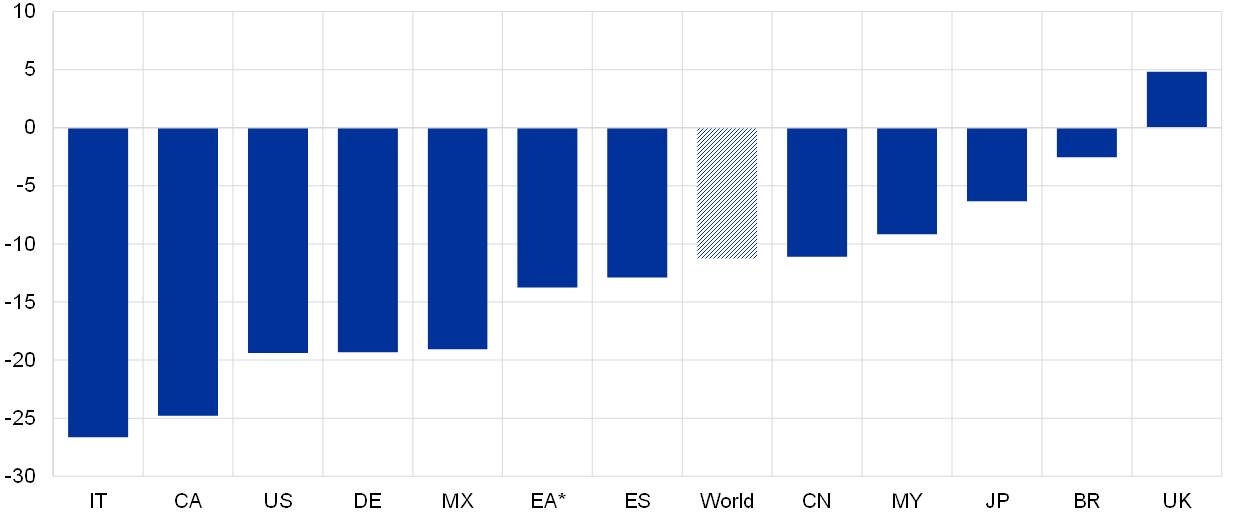

This misalignment between production and orders in some of the key manufacturing industries also points to supply bottlenecks. Thus far, the motor vehicle industry appears to be mostly affected by the chip shortage. In the first quarter of 2021, global production of passenger vehicles fell by almost 1.3 million vehicles, corresponding to a 11.3% decline against the last quarter of 2020 and to around a 2.8% decrease compared to the 2019 level of production (Chart E). Motor vehicle production in the euro area declined for four consecutive months up to March 2021, standing at 18.2% below its November 2020 level. In Germany, the monthly increase in manufacturing order backlogs consistently outstripped production growth between January and March 2021, particularly in the automotive and computer/electronic industries. This is confirmed by the ECB’s recent contacts with non-financial companies.[2] These contacts expected supply constraints to deteriorate in the second quarter of 2021 before gradually easing in the second half of the year.

Chart E

Global motor vehicle production

(passenger vehicles production, change between Q1 2021 and Q4 2020)

Sources: Haver, Eurostat and ECB calculations.

Notes: Countries are chosen on the basis of data availability and their global aggregate covers 70% of global motor vehicle production. Seasonally adjusted series. *EA data refer to euro area industrial production data, NACE2 code 29.1.

So far there is very limited evidence concerning the effects of semiconductor shortages on price developments along the pricing chain. Upward price effects could result, for example, from a scarcity of supply of goods, increasing pricing power at the different levels of the supply chain or from companies trying to pass on costs resulting from forced underutilisation in production. Euro area producer price inflation for both electronic components and boards, for which semiconductors play an important role, continues to remain negative (Chart F). At the later stages of the pricing chain, consumer price inflation for computers and motor vehicles (the two largest components in electronic consumer goods) reveals some increase for motor vehicles,[3] while prices for computers actually began to decrease again. However, it should be noted that upward price effects from semiconductor shortages might materialise but only with a substantial time lag along the pricing chain.

Chart F

Producer and consumer prices for products that rely on semiconductors

(annual percentage changes)

Sources: Eurostat and ECB staff calculations.

Notes: Dashed lines reflect series at constant taxes (assuming full pass-through of changes in indirect taxes, which include the temporary VAT cut in Germany). Latest observations are for April 2021.

The shortage of semiconductors is expected to persist in the near term. While the major global chip manufacturing firms plan to expand capacity and boost their capital expenditure by almost 74%, which is largely planned to be implemented by end-2021, both the complexity and the time required to build new plants is such that the industry’s headwinds are likely to remain throughout this year.