How Binondo Became the World’s Oldest Chinatown (original) (raw)

Today, Binondo is famous as the answer to the question: what is the oldest Chinatown in the world? It's a slice of China outside the mainland. The Binondo area, from the streets of Escolta and Divisoria to the bustle of Plaza San Lorenzo Ruiz all the way to Ongpin—and the many who lived there and contributed to its rich history—has had a huge influence on the rest of Manila, as well as the nation.

From Humble Beginnings

To fully understand Binondo, we must look to the people who built it: the Chinese-Filipinos. Even before the arrival of the Spanish, the islands of the Philippines were already brimming with Chinese traders, their goods, and their influence. Mindoro was a known trade port to the Chinese, who noted the island on their maps as the Kingdom of Ma-i.

Other states, such as the Rajanate of Butuan and the Kingdom of Tondo, had frequent trade with Chinese merchants. Chinese goods flowed from the port of Tondo and from there, across the archipelago. Wares reached as far as the Aeta tribes of the Cordillera in return for gold.

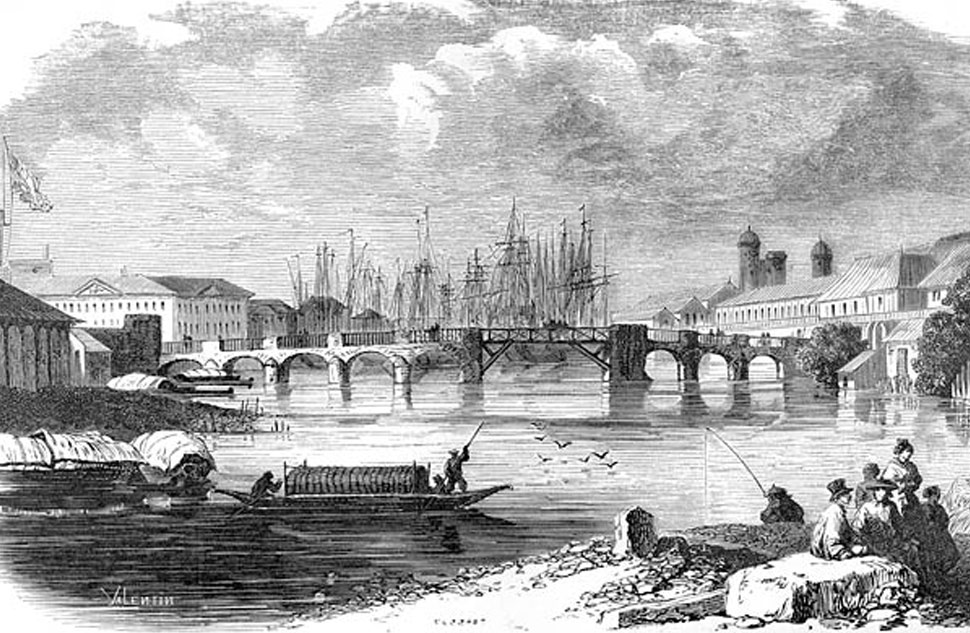

IMAGE: Wikimedia Commons - Henri Valentin

A reason why Legazpi moved his capital from Cebu to Manila was because of Chinese economic activity. Tondo was the beating heart of Luzon and the Pasig was its major artery. Chinese merchants, either looking for a profit or a new life, settled along the banks of the Pasig.

Most of the Chinese who settled in the Philippines came from Fujian or Guangdong, braving harsh waters and defying the will of the Ming Emperor himself, who forbade people from leaving China. This legacy of Hokkien-speaking migrants can still be felt today, from food to culture, and even the language we speak: Instik comes from the Hokkien in-chek, meaning “uncle.”

When the Spanish settled in Intramuros, they had to contend with multiple problems, chief of which was the sheer number of native Filipinos and Chinese compared to them.

Politically Untrustworthy, Economically Necessary

To deal with this, the Spaniards sought the alliance of local chiefs and pitted them against each other, essentially playing partisan politics against local politics.

The Chinese were a different matter. They were foreigners, yet also economically important to the Philippines and to Spain’s hopes of cornering the lucrative Chinese market. The colonial government was continually afraid of Chinese invasion, yet understood the importance of the Chinese. The pirate Limahong’s attack on Manila certainly didn’t help Spanish attitudes toward the Chinese.

Perhaps as a small measure of revenge, or perhaps due to racism, the Chinese were not allowed to live within Intramuros. Instead, they were forced to settle in a ghetto just outside of it, but within range of its cannons, known as the Parian. The area now stands as Plaza Lawton and the Arroceros Forest Park (Arroceros comes from its old name, Parian de Arroceros).

IMAGE: Wikimedia Commons - Alden March

Life within the Parian was harsh for a sangley (from Philippine Hokkien siong lai or "frequent visitor"), with extortionary taxes and rampant abuse by the Spaniards. Being a sangley meant you were the lowest of the low in colonial society.

In 1594, Governor-General Luis Perez Dasmariñas attempted to encourage cultural assimilation of the sangley community. He moved sangleys who had converted to Christianity from the Parian across the Pasig River to the area now known as Binondo. A more sinister reason might be to put some distance between the Spaniards in Intramuros and the Chinese in Binondo; Perez Dasmariñas’ father, Gomez, had been killed just the year before by 250 sangleys in a mutiny at sea.

Nevertheless, the Christian sangley community thrived in Binondo. The Dominicans established the Binondo Church and set about converting many residents to Christianity. The sangleys in Binondo gradually assimilated to colonial culture and received a small sense of security in their colonial status. Meanwhile, those who didn’t want to leave their heritage behind were left in the ghetto of the Parian.

The Massacre of 1603

By the 17th century, the Chinese minority was a staple of colonial dynamics. Though still untrusted, they had a small measure of autonomy, with their own governor. Events in 1603, however, rocked the community.

Three Chinese magistrates arrived in the Philippines and wished to investigate a “mountain of gold” somewhere in Cavite. The Spaniards, already wary of the colonial Chinese community, grew ever worried at the arrival and actions of these magistrates and feared a Chinese invasion.

IMAGE: Wikimedia Commons - Liane777

Though no invasion had been sanctioned by the Chinese emperor, the Spaniards didn’t want to take any chances and decided to take action against the Chinese community in the colony. Governor-General Pedro de Acuña decided to reinforce Intramuros and bought all weapons and armor from the sangleys in Parian. Tensions flared higher than ever.

On October 3, things came to a bloody end. Juan Bautista de Vera, the governor of the Chinese quarters, was arrested on suspicion of plotting a rebellion. Fearing they had been found out, Chinese rebels decided to attack early, moving from Tondo to attack the church in Binondo.

The rebels fortified themselves in the Parian and other areas of Manila before a combined force of Spanish, Filipino, and Japanese forces counter-attacked, crushing, scattering, and then massacring the rebels.

A Changing Culture

IMAGE: National Historical Commission of the Philippines

Relations between the Chinese sangleys and the rest of the colony remained low for centuries, though they became more accepted as they assimilated to the native indio class.

Over the generations, the Chinese elevated themselves in status through intermarriage and business ventures. Eventually, a mixed-race mestizo de sangley class emerged. These mestizos were far from the workers and tradesmen that were their ancestors; they were bourgeois, educated, leaders of the economy. Their sons went on to study at prestigious colleges, and even Europe to learn liberalism. They called themselves enlightened, ilustrado.

Binondo itself changed. Though its residents went on to embrace colonial culture, they never dared forget their roots. Incense burned in front of the Virgin Mary in Binondo Church. Artisans plied their craft and wove lions and chrysanthemums in their stonework and embroidery. Food became a staple of the Chinese-Filipino, with lumpia, tikoy, pancit, mami, and so many other dishes still enjoyed today. At its center was Ongpin Street, an enduring reminder of Chinese heritage in Binondo.

IMAGE: Wikimedia Commons - Ramon FVelasquez

Economics shaped the face of Binondo. From merchants and tradesmen setting up shop and business, it grew to larger capitalist enterprise. Escolta became the center of commercial activity before the Second World War and was deemed the “Broadway of Manila” by the Americans. Quiapo and Divisoria was, and still is, the place to go for anything from petty baubles to wholesale reselling. Major banks established themselves in Binondo before branching out nationwide. Though racism and war ravaged Binondo, and the Tsinoys who lived there with it, they persevered and grew stronger.

The story of Binondo is the story of the Chinese-Filipino. Seizing opportunity at a time of political uncertainty, Binondo went from just another enclave of Chinese in Manila: It became a part of the Filipino psyche itself. Today there are no more sangleys or mestizos or intsiks. There are only Filipinos in Binondo.

Sources:

Bahay Tsinoy Museum of Chinese in Philippine Life, Intramuros, Manila

Cabreza, V. (2014, January 31). Is ‘Intsik’ a racial slur? Chinese-Filipino prof in US says it’s not. Inquirer.net.

Borao, J. E. (1998). The massacre of 1603: Chinese perception of the Spaniards in the Philippines. Itinerario, 23(1), 22-39.

Soriano, E. (2017, February 11). Binondo: the Oldest Chinatown. Inquirer.net.

Lazatin, H. (2018, January 13). The Glory Days of Escolta, Manila’s ‘Queen of the Streets’. Town & Country.