German elections: how the right returned (original) (raw)

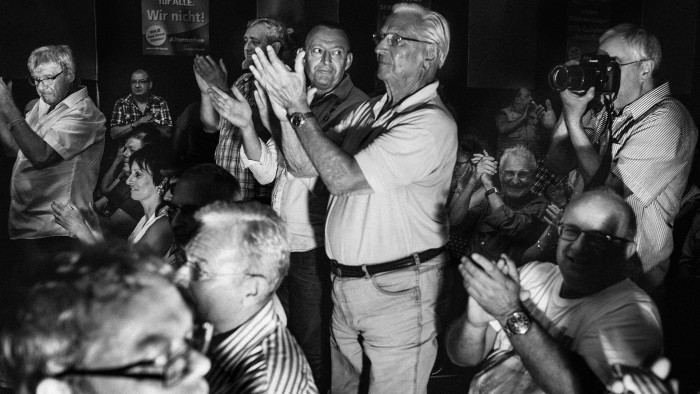

Audience members applauding speakers at an AfD rally in Helbra, Saxony-Anhalt, east Germany, last month © Hannes Jung

Björn Höcke has a stark message for the thousands of migrants who have braved the hazardous waters of the Mediterranean this year. “Dear young African men,” the politician told a rally in East Germany last month. “We know you’re seeking your fortune, but you won’t find it here with us. No way, dear young African men: for you there is no future and no home in Germany and in Europe!”

Cue rapturous applause from his audience, a 1,000-strong mainly male crowd crammed into a former slaughterhouse in the small town of Helbra. Hundreds rose to their feet, cheering, clapping and roaring “Höcke, Höcke!” Their hero, a history teacher-turned-nationalist firebrand, basked in the adulation.

Höcke is one of the most recognisable faces of the Alternative for Germany (AfD), a party that burst on to the scene four years ago as a noisy Eurosceptic outfit and has since grown into one of the most dynamic — and provocative — forces in German politics. Injecting controversy and conflict into a system built on consensus and compromise, it is a Molotov cocktail lobbed at the very heart of the Berlin Republic.

It is now poised for a major breakthrough. When Germans go to the polls on September 24, the AfD is likely to win about 50 seats — possibly more — in the Bundestag, making it the first rightwing party since the 1950s to sit in the German parliament.

Björn Höcke, the standard-bearer of the AfD’s right wing, speaking in Helbra © Hannes Jung

For decades, no one thought such a thing was possible: Germany’s Nazi past seemed to have immunised it against the appeal of hard-right nationalism. Not any more. “Historically speaking we are the most successful newly created party in postwar German history — and the most necessary one,” Höcke told the crowd at Helbra.

The AfD is part of a populist wave that delivered the Brexit vote in the UK, Donald Trump’s victory in America and brought Marine Le Pen to the second round of the French presidential election. It is one of a clutch of new anti-establishment parties that have sprung up to harness voter discontent and give a voice to people ignored by a supposedly rigged system run by unaccountable elites.

But the AfD would never have achieved its success without Angela Merkel, Germany’s long-serving chancellor, and her decision in 2015 to let a million refugees into the country. That created an opening for the party, allowing it to exploit the fears and resentments of huge swathes of Germans who opposed the influx. In Helbra, her name drew boos and whistles from the crowd. “Traitor!” one man shouted.

The object of their wrath now faces a conundrum. Merkel is widely expected to win a fourth term this month. But a strong showing by the AfD will make it much harder for her to form a government than in the past, when fewer parties were represented in the Bundestag. Some predict she may be forced to cobble together a coalition of three parties — an outcome that could condemn Germany to a period of turbulence that would require all the chancellor’s political skills to navigate.

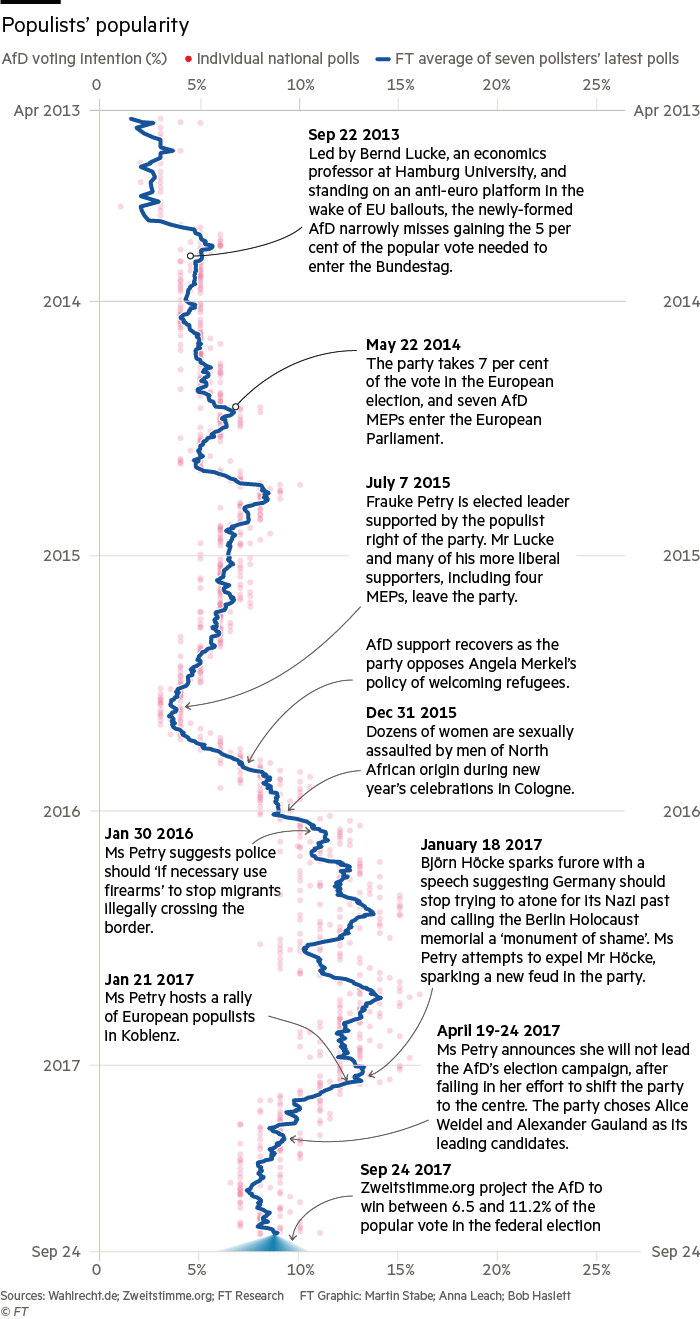

But the strong likelihood of election success next month masks a disturbing fact for the AfD: it is a lot less popular now than it was even six months ago. Ideological squabbles, internal power struggles and a marked shift to the right have put off middle-of-the-road voters, driving down its poll ratings from 16 per cent last September to about 9 per cent now.

Some think the party is too hard right to ever achieve more than that. “The AfD says it speaks for the nation, but in fact they only represent a radical minority,” says Manfred Güllner, head of pollster the Forsa Institute. “They will only ever appeal to the 10 per cent of the German electorate who have radical rightwing views.”

Alexander Gauland, one of the AfD’s leaders, puts the party’s problems down to a lack of discipline. It is a “bunch of anarchists” who are “constantly in ferment”, he says. “There’s a lot of stupidity. People are just running riot.” Yet Gauland himself embodies the problem. He recently attacked Germany’s commissioner for migrant integration, Aydan Özoğuz, who has Turkish roots, for saying there was no such thing as a “specific German culture”. Özoğuz, he said, should be “disposed of” in Anatolia, using the word Germans normally use for rubbish. Merkel accused him of racism.

Perhaps even more controversial than Gauland, though, is Höcke, the standard-bearer of the party’s increasingly vocal right wing and the star attraction in Helbra. In January he suggested Germany should stop atoning for its Nazi past, and called a tribute to the murdered Jews of Europe near Berlin’s Brandenburg Gate a “monument of shame”. It was a breaking of the ultimate taboo, challenging the central place of remembrance and repentance in Germany’s postwar political discourse.

The speech caused howls of protest, not only from politicians in other parties but also from moderates in the AfD itself, who launched proceedings — so far unsuccessful — to have Höcke excluded. “He crossed a red line for me,” says Alice Weidel, 38, an openly lesbian economist who is one of the AfD’s top two candidates in the Bundestag election. “Sometimes people just go too far.”

But the AfD also faces an external threat that is almost as big as its internal squabbles. The refugee influx, once the most incendiary issue in German politics, has rapidly faded from view. The flood of migrants seen in 2015 has slowed to a trickle: those already here are busy integrating into German society. The AfD warned of an orgy of crime, a wave of terror and social breakdown. But this dystopian vision — a kind of Trumpian “German carnage” — has failed to materialise.

“You see that people are a lot calmer now that the numbers of refugees coming into the country have gone down — and the AfD’s ratings have fallen,” says Özoğuz. “No party can really build its support on this issue in the long term.”

It’s all a far cry from the glory days of late 2016. In January, party leader Frauke Petry hosted a rally in Koblenz that brought together the leading lights of the European right — from Marine Le Pen to the Dutch Party for Freedom’s Geert Wilders. Held seven months after the Brexit vote and a day after Donald Trump’s inauguration, it reflected a new confidence among Europe’s rightwingers. “We are experiencing the end of one world and the birth of a new one, full of hope,” Le Pen, leader of France’s National Front, told delegates. Then she turned to Petry. “You will rule Germany!” she bellowed.

Koblenz proved to be a high watermark. Neither Le Pen nor Wilders won their respective elections. And three months after the NF leader anointed her as a future chancellor, Frauke Petry was laid low by powerful enemies within the AfD: her days as party leader may now be numbered.

The AfD was formed in 2013 in protest at the eurozone bailout of Greece. “I was outraged at how it was implemented over the heads of the European parliaments,” says Konrad Adam, a former senior editor at the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung and one of the party’s founders.

Led by Bernd Lucke, a professor of macroeconomics at Hamburg University, it quickly established itself as an economically liberal party with a strongly Eurosceptic bent. Its name was telling: Merkel had said there was “no alternative” to the Greek bailout. Lucke and his fellow professors insisted there was and created a party to prove it.

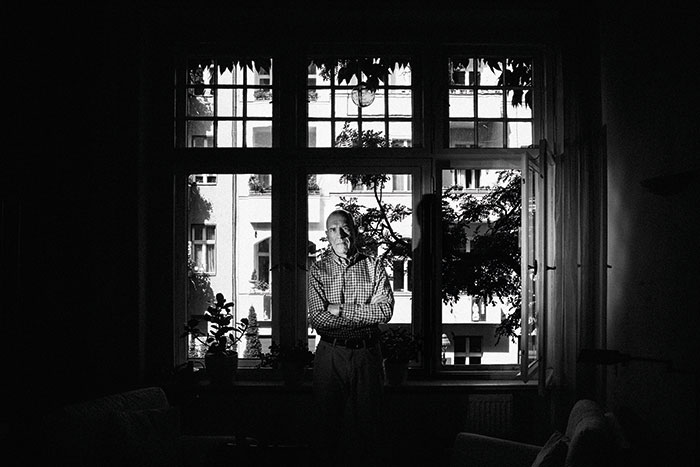

Initially, it attracted upstanding conservative burghers who felt the EU was breaking its own laws. One early convert was Michael Seyfert, a 65-year-old retired radio journalist from the well-to-do Berlin neighbourhood of Wilmersdorf. “There is the Maastricht Treaty, which says that no country will have to pay for the debts of another country, and this was broken,” he says.

AfD moderate Michael Seyfert, in his flat in Berlin: “I don’t want anything to do with nationalistic or rightwing extremists or anti-Semites” © Hannes Jung

Seyfert seems an unlikely AfD supporter. In the 1960s, he had long hair, played drums in a band and smoked “big joints”, he says. He still listens to Bob Dylan, and is a keen amateur painter. “My son says, ‘Oh you’re so conservative, with your sex, drugs and rock and roll,’” he says. He now combines painting and running marathons with service as an AfD councillor in Wilmersdorf, where the party won 9.7 per cent in elections last year. He counts a lawyer, civil servant and businessman among his party colleagues. Such people, he says, feel they’ve been “taken for a ride by the government”.

That points to one of the AfD’s most important distinguishing features. Other populist parties, such as France’s National Front, draw their support from the unemployed, the “left-behind” and the “precariat” — people robbed of their economic security by globalisation. But a recent study by Oskar Niedermayer, a politics professor at Berlin’s Free University, found that AfD supporters were different. Most had jobs: they also earned more and were better educated than the average German. In a survey last year, 80 per cent described their economic situation as “good” or “very good”.

According to Melanie Amann, author of a bestselling book on the AfD, the party holds a mirror up to the whole of German society. “AfD voters are men and women, from east and west, the ‘establishment’ and the ‘mob’,” she writes. “They are retired teachers and young students, well-off lawyers and single-parent-hairdressers, ethnic Russians and even the children of Turkish parents.”

One of the largest wellsprings of AfD support were defectors from Merkel’s Christian Democrats who felt she had pushed the party too far to the left. Gauland, a 76-year-old former newspaper publisher, is the AfD’s deputy leader. A CDU member for 40 years, he now considers the party an “empty shell . . . constantly chasing the latest trend in public opinion”.

He was enraged by Merkel’s decision to shut down Germany’s nuclear power stations following the 2011 Fukushima disaster, and to abolish military conscription. He also resented the way he and other members of the “Berlin Circle”, a conservative group within the CDU, were snubbed by the party leadership. “They said we were yesterday’s men,” he says.

From the start, the AfD attracted people with strongly nationalistic views — such as André Poggenburg, a businessman from the east German region of Saxony-Anhalt, which quickly emerged as a stronghold of the party. Having grown up under communism, Poggenburg says he’s less hung up about patriotism than people in West Germany, who often equate national pride with Hitler and the Third Reich. “In the communist GDR we had the National People’s Army,” he says. “There are two words there that you can’t say nowadays.”

Lead AfD candidate Alice Weidel talking to supporters in Gütersloh, North Rhine-Westphalia © Hannes Jung

The growing influence of people like Poggenburg and Höcke worried Lucke and his moderate camp. But their attempts to curb the rightists’ influence ended in disaster. At a party conference in 2015 Lucke was swept from power in a coup that established Petry as the unrivalled leader. Hundreds of loyalists quit in protest.

Lucke has little interest in the current AfD. “[Its] views are opposite to the ones I had when I founded it,” he says. But he acknowledges the appeal. “When I led it, I had the support of 7 per cent [of voters]. That doubled when they became anti-Islam and anti-immigrant.”

Indeed, the refugee surge of 2015 gave a new lease of life to an organisation that, after the schism with Lucke, was languishing in the polls. It quickly downgraded its previous anti-EU stance and refashioned itself as an anti-immigration party. That suited members like Michael Seyfert, who found Merkel’s refugee policy as legally questionable as the Greek bailout. “In Germany, if you go fishing without a licence you’re in trouble,” he says. “But on the other hand, you let hundreds of thousands of people in without registering them. That’s completely idiotic, in a way.”

The AfD demanded immediate restrictions on immigration. Party leader Petry went further, saying in January last year that German border guards had the right to use firearms if necessary to control migrant flows.

The remark caused a furore but also served a purpose, firmly establishing the AfD as the only real opposition party in Germany — at least when it came to immigration. The CDU and its junior coalition partner, the Social Democrats, as well as the Greens and the leftwing Die Linke, all backed Angela Merkel’s open-door policy.

Hans-Thomas Tillschneider, a rightwing AfD MP in Saxony-Anhalt and a Poggenburg ally, says the party presented itself as an alternative to Germany’s stiflingly consensual style of politics, where all big parties agree on most big issues, from eurozone policy to immigration. “The AfD . . . made democracy possible again,” he says. “We got rid of this logjam in our democratic process, this malfunction.”

André Poggenburg, the AfD leader in Saxony-Anhalt, a party stronghold, at the state parliament © Hannes Jung

Soon, events were conspiring to bolster the AfD’s demands for a tougher border regime. On New Year’s Eve 2015, dozens of women in Cologne were sexually attacked by men of north African origin. Suddenly, the mood in Germany changed. The “_Willkommenskultur_” or culture of welcome, epitomised by crowds handing gifts to newly arrived refugees the previous September, was replaced by a new scepticism.

This intensified over the course of 2016, when Germany was rocked by a string of terror attacks perpetrated by refugees. The worst occurred in December, when a failed asylum seeker from Tunisia drove a truck through a Berlin Christmas market, killing 12 people. As public doubts about the migrant influx mounted, the AfD’s ratings soared.

Under Petry’s charismatic leadership, it scored impressive results in a string of regional elections, even in well-heeled states like Baden-Württemberg, home to Daimler and Porsche. In Saxony-Anhalt it won 24.3 per cent of the vote — its best-ever result — and became the second-largest force in the local parliament. In September it stunned Merkel’s CDU by beating it into third place in the rural state of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, the chancellor’s home turf.

Rene K is a volunteer fireman in the Saxony-Anhalt town of Bitterfeld, where the AfD won 32 per cent — a record at the time. He voted for the party last year because of its stand on the refugees. “Most of them just go, ‘Oh man! Germany! Merkel! Money!’” says Rene, who declines to give his surname. “It’s a mystery to me why they get more than pensioners who have lived here all their lives.”

Back in May, a group of AfD supporters gathered in a pub in Sigmaringen, a prosperous town in Baden-Württemberg, to discuss the refugee problem. The guest speaker was Karl-Heinz Hulin, a local man whose adopted daughter, Isabelle Kellenberger, was found dead in a river last year. The police said she had killed herself.

Hulin believes she was murdered. His suspicions rest with a group of refugees housed in a hostel 15 minutes by foot from where her body was found. In the days before her death, Isabelle “was stalked by asylum-seekers”, he told the audience. There had been police raids of the hostel: drugs were found, he said. He suspects a cover-up.

Hulin offered no proof. But most of the audience seemed to believe him anyway, judging by the angry mutterings and sharp intakes of breath. The event was one of hundreds of “civic dialogues” the AfD has organised in small towns across Germany to tap rising anxiety about immigration. Among those listening was Walter Schwaebsch, a management consultant and local AfD activist. “There’s been a lot more crime here since the refugees came — rapes, murders — and people are becoming alert to it,” he says. “The other parties make out everything’s fine and dandy. We deal in facts.”

The meeting had been arranged by Alice Weidel, who hails from these parts. A fluent Mandarin speaker who spent years as a researcher in China and once worked for Goldman Sachs, she describes herself as an “Ur-liberal” taking up arms to defend German democracy. Everywhere she looks, she sees institutions breaking the law, she says, whether it’s the government throwing open the country’s borders or the European Central Bank buying government bonds: “I see the rule of law being eroded — it’s like sand slipping through my fingers. There’s no sound legal foundation, and it makes me very nervous.”

However, not everyone in the party is “Ur-liberal”. Indeed, by last year some members were beginning to worry the AfD had been infiltrated by the hard right. One was Thomas Traeder, a political scientist from Cologne: he noticed that another AfD member from his local branch was repeatedly “liking” anti-Semitic posts on Facebook. One read: “Merkel the Zionist Jew is selling out Germany and wants to destroy the people of Europe. That is her Jewish task.” The man himself wrote a post suggesting Jewish organisations were pursuing a plan to “ethnically dilute” the German nation.

Alexander Gauland, the AfD’s deputy leader, in his office in Brandenburg’s state government, Potsdam © Hannes Jung

Traeder reported the posts to the local AfD leader. “He screamed at me, saying there was nothing anti-Semitic about them, and that he wondered whether there was a place for me in the party,” he says. In January, Traeder left the AfD. “There are more and more rightwing radicals joining up. You wonder whether to leave, or wait to see if they’ll be chucked out. But it doesn’t work, because there’s just too many of them.”

It wasn’t just in Cologne. Across Germany, the ranks of rightwingers within the AfD were swelling, nowhere more so than in Saxony-Anhalt. Earlier this year, three MPs quit the AfD parliamentary group over what they saw as the party’s rightward lurch. One was Jens Diederichs, a prison officer-turned-politician. “I was finding more and more that rightwing ideas were taking hold of the party, and you start asking yourself whether you’re barking up the wrong tree,” he says.

Several leading AfD members were, he says, openly consorting with the Identitarian Movement, a radical white-nationalist and anti-Islam organisation which has long been under surveillance by German intelligence. The AfD’s national leadership last year explicitly banned any co-operation with the Identitarians. “But that decision is just being completely ignored,” Diederichs says.

Matthias Quent, a researcher at the Institute for Democracy and Civil Society in Jena, says he has recorded numerous “intersections” between the AfD and hard-right organisations, ranging from radical Burschenschaften or student leagues, hooligan gangs and neo-Nazi groups. “The far right, particularly in East Germany, increasingly sees the AfD as its parliamentary arm,” he says.

André Poggenburg, who now leads the AfD in Saxony-Anhalt, has himself excited controversy. Earlier this year he received an official warning from the party leadership after using the phrase “Germany for the Germans” in a leaked AfD WhatsApp group discussion. He also once described leftwing extremists as a “tumour on the German national body”, in an uncomfortable echo of Nazi rhetoric. “Of course we are trying to provoke,” Poggenburg says. “But freedom begins with freedom of speech.”

Party leaders have tried to stop the rightward shift. At an AfD conference in April, Frauke Petry sponsored a motion distancing the party from racists, anti-Semites and neo-Nazis, and shifting its stance from that of “fundamental opposition” to “realpolitik”. Her motion didn’t even make it on to the conference agenda.

Petry also earned the lasting hostility of rightwingers for spearheading an effort to exclude Björn Höcke from the party, in the wake of his “memorial of shame” speech. Gauland firmly opposed the initiative. A third of the AfD are “passionate Höcke supporters”, he says. “If you exclude him, you’re insulting the most active members of the party.” The AfD must, says Gauland, continue to “walk a tightrope”, maintaining its role as a “radical protest party” while not tilting too far to the right.

Rightwingers such as Hans-Thomas Tillschneider say that, in any case, Höcke said nothing wrong. Germany had to end its obsession with its war guilt. “The more time elapses since the war, the longer Hitler’s shadow becomes,” he says. “That’s unnatural. We have to learn to leave the past behind.”

Others disagree. Konrad Adam, the AfD co-founder, is repulsed by Höcke and his views. “I’m no friend of his,” he says. “His way of speaking reminds me of Joseph Goebbels.” He says the rot set in with the departure of Lucke and the liberals. Ever since, the AfD has been “wracked by inner turmoil — and that’s something voters really don’t like”. Michael Seyfert, who is typical of the AfD’s more moderate wing, is also wary of Höcke, believing he and others like him should be expelled. “I don’t want anything to do with nationalistic or rightwing extremists or anti-Semites,” he says. “I find that very unfortunate, unappetising and horrible.”

Some predict that the AfD could suffer another damaging split between moderates and radicals. Others think it will merely fade into irrelevance. But one thing is clear: it has already reshaped the political landscape, and pushed the boundaries of what is and isn’t sayable in modern Germany. The recent rightwards tilt of Merkel’s CDU, particularly on asylum and the importance of German identity and culture, is part and parcel of the “AfD effect”.

Many point to Frauke Petry’s attempt last year to rehabilitate the word völkisch, the German word for “folk-y”, or “ethnic” — which for many still has Nazi overtones. “Politicians of other parties would never have come up with such an idea,” says Hendrik Träger, a political scientist at Leipzig University. “They would be tarred and feathered for using a word like that.” He says if the AfD enters the Bundestag, it will inject a new dynamic into German politics. “Germany sometimes feels like it’s in a deep sleep — partly because of Merkel,” says Träger. “There’s no doubt the AfD will change the culture of debate in parliament.”

Back in Helbra, Höcke leaves the stage and, after a quick burst of the German national anthem, heads for the exit. He brushes off a reporter’s question about the AfD’s low poll ratings. “Voters are very volatile at the moment,” he says. But the party, he adds, is set for an electoral breakthrough. “We are going to have a marvellous result in the end.” And with that, he’s gone.

Guy Chazan is the FT’s Berlin correspondent . Photographs: Hannes Jung

What do you think: can an opposition party like the AfD, which unites hard-right nationalists and moderate conservatives under the same roof, survive long-term - or will it inevitably split? Tell us your thoughts in the comments below. Guy Chazan will be responding intermittently.