Here's how a secluded Polish studio was called upon for The Witcher Remake, Baldur's Gate 3, and Divinity 2 (original) (raw)

(Image credit: IMGN.PRO)

During the half-decade he worked at CD Projekt Red, Jakub Rokosz rose to the rank of senior quest designer and contributed to Geralt's two most beloved adventures: The Witcher 2: Assassins Of Kings and The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt. Yet he couldn't shake the sense that he'd arrived late. "It always bothered me that I missed the first [Witcher game]," he says. "I wanted a chance to give it the justice it deserved." Several years later – and by then the CEO of his own studio – Rokosz met with a few former colleagues to reminisce about the fun they'd had developing one of the best RPGs of all-time. And just a few weeks after that, CDPR studio head Adam Badowski called with a proposal: that Rokosz and his team tackle the remake of the very first Witcher game. The one he hadn't managed to put his stamp on.

Rokosz calls it serendipity, and there's a certain amount of romance in the telling of his story. Yet he's clear-eyed about the task ahead. "First and foremost, we need an honest, down-to-earth analysis of which parts are simply bad, outdated, or unnecessarily convoluted and need to be remade," he says, "While at the same time highlighting the parts that are great, should be retained, or are direct key pillars that can't be discarded." After that, Fool’s Theory can begin the redesign process: "This involves removing the bad parts and rearranging the good ones to create something that is both satisfying and still resonates with the feel of the original."

Serendipity

(Image credit: Just A Game GmbH)

Game development is as much about throwing work away as it is creating something new. That's a lesson Rokosz learned early, alongside Fool's Theory co-founder and art director Krzysztof Maka, when they both contributed to a forum-run project named Bourgeoisie. Initially a post-nuclear isometric RPG made by Fallout fans, it was boiled down over time to a survival horror game – which secured funding and was released in 2011 as Afterfall: Insanity.

"This served as my first real lesson in project scope," Rokosz says. Some of that team clung onto the dream of making an old-school RPG, however. And so, after careers made in Warsaw at the likes of CDPR and Flying Wild Hog, they reunited in Rokosz’s hometown of Bielsko-Biała to found a new studio, with friends gathered along the way. "We were tired of the big-city life and the ridiculous hours spent in traffic commuting," Rokosz says. The pace of life in Bielsko-Biała couldn't be more different: nestled among the forested Beskid mountains of southern Poland, the city's population is an order of magnitude smaller than that of the capital.

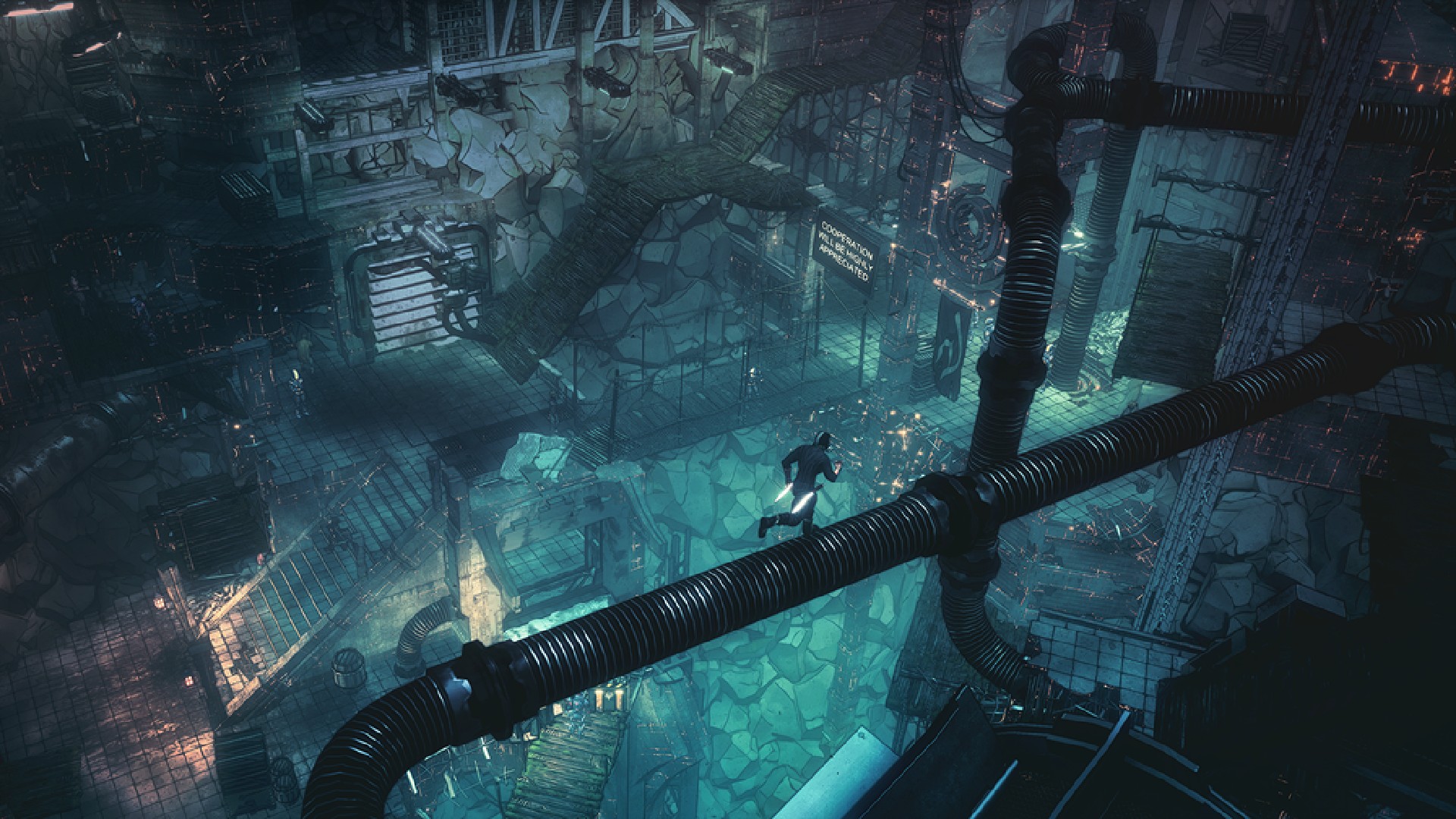

It was here, working as a team of five, that Fool's Theory conceived Seven: The Days Long Gone. Like Bourgeoisie before it, this was a post apocalyptic world explored from an isometric perspective, drawn from Rokosz's "obsession with systemic game design and the freedom of choice the Fallout series offers". It was made possible by a partnership with publisher IMGN.PRO, whose staff could make up the numbers Fool's Theory was lacking. "As luck would have it," Rokosz says, "developers working in that department were my childhood friends with whom I had always wanted to create a game." More serendipity. "To be able to make the game of your dreams, with childhood friends, in your hometown? Who wouldn’t agree?"

Subscribe

(Image credit: Future PLC)

This feature originally appeared in Edge Magazine. For more fantastic in-depth interviews, features, reviews, and more delivered straight to your door or device, subscribe to Edge.

Seven was, by Rokosz's admission, "my ugly mashup child of fantasy, sci-fi and cyberpunk inspirations, with its story primarily serving as a backdrop for the game's systems". Immersive-sim-style stealth rubbed up against rooftop parkour and an impudent thief who shares his head with a disapproving AI. Players could unlock fast travel across its open world by hacking its transit system. Not every element shone, but against the odds, it all came together – a game without any obvious genre-mate, at least until Weird West rode into town four years later. "Seven was a fantastically chaotic project in some respects," Rokosz says. "But we love it all the same, and fans continue to appreciate it to this day."

While not exactly a commercial success, Seven put Fool's Theory on the radar of like minded studios with deeper pockets. It's easy to see the philosophical crossover with fellow systemic-obsessive Larian Studios, which tasked Fool's Theory with developing free DLC for Divinity: Original Sin 2 and fleshing out Baldur's Gate 3's programming features. The former task proved tricky, given that Larian left very little real estate in Rivellon unpopulated by side stories or combat encounters. Fool's Theory wove its work masterfully into the existing game, however: playing its quests during the course of Divinity's campaign, you might never realise they were squeezed in after the fact. "Having the opportunity to learn about the business from [Larian's] Swen Vincke was an eye-opening experience," Rokosz says.

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

Keeping your friends close

(Image credit: 11 bit studios)

Seven also caught the attention of 11 Bit Studios, the Polish powerhouse behind This War Of Mine, Frostpunk, and recent Edge cover game The Alters. The success of its harrowing survival management sims allowed 11 Bit to invest in local talent as a publisher, and led to the signing of Fool's Theory's next game, The Thaumaturge, a post-Disco Elysium RPG set in a supernaturally tinged, turn-of-the-century version of the very town these developers were escaping: Warsaw. Since then, 11 Bit has doubled down on its investment, acquiring 40 percent of Fool's Theory's shares and helping the studio "transition from our wild indie days and workflows into a properly managed company". This stability has enabled Fool's Theory to grow to 80 employees while retaining its creative freedom.

"The Thaumaturge is Seven’s older, wiser and more articulate sibling," Rokosz says. "The narrative is much more mature. The characters are better developed." Where Seven pulled from the medieval sci-fi of authors like Mark Lawrence and Scott Lynch, The Thaumaturge is rooted in real events in Polish history, and the literature of the early 20th century. Design director Karolina Kuzia-Rokosz and her team conducted extensive research, which in turn informed the game's world of Russian soldiers, Jewish merchants, Polish townspeople, and unearthly demons tied to human hosts.

Kuzia-Rokosz identifies overlapping themes with Seven. "We enjoy witty humour and cheeky ruffians," she says. "Our stories often revolve around morally ambiguous choices, internal conflict and the essence of what makes us human." It's perhaps telling that every Fool's Theory game features a party, the perfect way of exploring the human capacity for both wit and conflict in one place. "Nothing is ever simply black or white," Kuzia-Rokosz says. "The imperfections of human characters are what drive us to tell complex stories, allowing players to relate to them in one way or another, and to hope that each story could be a lesson of sorts." And indeed, parties aside, The Thaumaturge is a darker tale than Seven, and one that, despite presenting you with a fixed protagonist in Wiktor Szulski, leaves room to define his character with your own decisions.

To be able to make the game of your dreams, with childhood friends, in your hometown? Who wouldn’t agree?

Jakub Rokosz

Between projects such as The Thaumaturge and Slavic city-builder Gord, there's been a clear shift in Polish games towards celebrating the country's past and folklore. And why not? The Witcher has created a huge international appetite for knotty, morally ambiguous stories inspired by Poland's background as an occupied state, as well as the eerie magic of its legends. For Fool's Theory, that shift represents an opportunity to escape the usual trappings of high fantasy, with its winged wyrms and knights in armour.

"There’s nothing inherently wrong with generic dragons, but we always strive to create content that reflects and builds upon our own experiences and the environment we live in," Rokosz says. Naturally, then, they turned to the superstitions of their homeland, and to its tumultuous history, "because those elements ultimately shaped us into the developers we are today." It helps, we imagine, that Fool's Theory works in close proximity to Poland's past, working out of the same 19th-century building in Bielsko Biała's centre where the studio started out. "The only change," Rokosz says, "is that we moved down one level from the attic where we began."

Rokosz still talks wistfully about the "garage days" of Polish game development, before open engines and online tutorials, when tools and knowledge were hard to come by. "You either learned to overcome seemingly insurmountable challenges, or you shifted to a different profession," he says. "To be honest, we're not alone in this mindset. It's a common trait among many Polish game developers who began their careers at around the same time."

(Image credit: IMGN.PRO)

Related

Fool's Theory is currently developing a remake of The Witcher, but there's still plenty more to come out of that universe. Check out all the upcoming CDPR games to learn more.

Many of the friends that Fool's Theory's founders met working on Afterfall, or crossed paths with during the years afterwards, now run their own companies – or are responsible for the hit productions for which the Polish industry has become known. "I guess we learned quite early in our careers that with sufficient preparation and self-confidence, great things are achievable." Rokosz points to Tetris creator Alexey Pajitnov, along with Shigeru Miyamoto and John Carmack – pioneers who had no established roads to follow. "In that regard, we're just toddlers standing on the shoulders of these giants," he says. "When you consider what our predecessors achieved, you realise that the problem isn't ambition, it's a lack of proper preparation."

Now, as Fool's Theory wraps up work on The Thaumaturge and turns its attention to The Witcher Remake, preparation is front of mind. CDPR's Badowski announced the studio's involvement in 2022, with considerable fanfare and not a little pressure: "They know the source material well, they know how much gamers have been looking forward to seeing the remake happen, and they know how to make incredible and ambitious games. And although it will take some time before we're ready to share more about and from the game, I know it'll be worth the wait." Rokosz sees the project as another step in his studio’s growth. "Naturally," he says, "we need to scale up, in terms of team size and technological capabilities."

Fool’s Theory plans to expand over the next few years and bring its headcount to 140, a figure representing new seats in both the studio's development departments and its back office. While Rokosz doesn't foresee a return to Warsaw, he admits that the "secluded setting" of Bielsko-Biała initially posed a recruitment challenge. This has been solved, in part, by the shift in developer mentalities brought on by the pandemic, and the studio's adoption of remote working. ("We don’t require anyone to relocate," Rokosz says. "Although we highly recommend it. Our mountains are awesome.") The challenge now for Fool's Theory will be not just to live up to the expectations of Witcher fans, but to do so while retaining the voice that gained the ear of its peers in the first place. Which are, we might suggest, the same qualities that powered Seven’s protagonist, Teriel: an audacious ambition, offset by a cheeky grin and a winning ability to punch above their weight.

This feature originally appeared in Edge magazine. For more fantastic features, you can subscribe to Edge right here or pick up a single issue today.

Jeremy is a freelance editor and writer with a decade’s experience across publications like GamesRadar, Rock Paper Shotgun, PC Gamer and Edge. He specialises in features and interviews, and gets a special kick out of meeting the word count exactly. He missed the golden age of magazines, so is making up for lost time while maintaining a healthy modern guilt over the paper waste. Jeremy was once told off by the director of Dishonored 2 for not having played Dishonored 2, an error he has since corrected.