The architectural history of international organizations in Geneva (original) (raw)

By Joëlle Kuntz* Translated by Viviane Lowe

Introduction

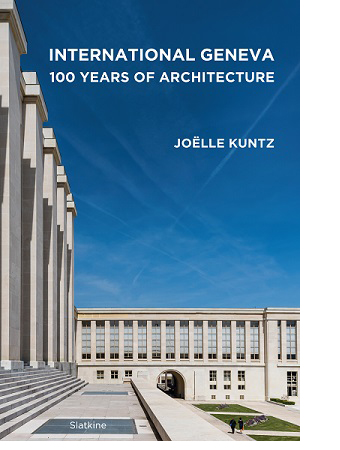

It was an honour for Geneva to be chosen to host the League of Nations’ headquarters in 1920, soon after the end of the First World War. The city scrambled to provide office space for the "internationals", housing for their families, and schools for their children. The following articles chart the hundred-year history of this endeavour. They present the main architectural achievements of the area now known as the “Garden of Nations”, recount the challenges and problems that their builders faced and the solutions they found, and trace the evolution of architectural taste across the century, from classicism to modernism to the eclecticism of the present day.

It was an honour for Geneva to be chosen to host the League of Nations’ headquarters in 1920, soon after the end of the First World War. The city scrambled to provide office space for the "internationals", housing for their families, and schools for their children. The following articles chart the hundred-year history of this endeavour. They present the main architectural achievements of the area now known as the “Garden of Nations”, recount the challenges and problems that their builders faced and the solutions they found, and trace the evolution of architectural taste across the century, from classicism to modernism to the eclecticism of the present day.

The international quarter’s built environment reflects the main architectural movements of the twentieth century. It was never pioneering – unless, as Le Corbusier said, tradition is merely the accumulation of innovations. Its forms, materials, and techniques were inspired by what was being done elsewhere, in Europe and the Unites States. Its unique character comes from the methods used to decide what to build: a complex, subtle dialogue between local opinion, eager to please but wary of unchecked development, and the international organizations, beholden to their members’ approval.

The host city, though welcoming, imposed its aesthetic inclinations, which precluded any and all extravagance in height or style. In square-meter terms, grandiosity was allowed as long as it was horizontal: nothing could stand higher than Saint-Pierre Cathedral. A forest of skyscrapers facing the Alps would have insulted Mont Blanc. This unwritten constraint bothered architects more than their patrons, who embraced the Genevans’ affection for a gloriously untouched setting that embodied their ideals.

Negotiations between Geneva and its foreign guests centred on the amount of land assigned to them (which was never enough), the allocation of construction costs (both foreseen and unforeseen), and living conditions for the buildings’ occupants. International institutions, answerable to their members around the world, placed demands on Genevan and Swiss authorities, who were in turn answerable to local voters. Two distinct political and administrative perspectives thus coexisted, agreeing most of the time, clashing on occasion, and resorting to blackmail in rare cases – when a disgruntled organization threatened to leave, as happened more than once.

This architectural cohabitation unfolded in four main stages: the years 1922–26, which witnessed the irruption of the ILO building in the idyllic, nineteenth-century setting of Romantic Geneva; the years 1927–37, dominated by the great polemic between modernist and classical architects over the building of the Palace of Nations; the years 1950–65, with the triumph of modernism, represented by Jean Tschumi's WHO headquarters; and the turn of the twenty-first century, which has seen the emergence of an eclectic architecture without schools or factions, a licence to do as you please, provided it has value and makes sense. The WMO building perfectly embodies this final stage.

We selected 15 of the most significant buildings from among the hundreds that play host to the many international institutions, non-governmental organizations, and diplomatic missions in Geneva today. Each in its way influenced the development of architecture in the international quarter, once on the margins of the city but now an integral part of it.

The history of these buildings is also that of the countless political and technical adjustments needed to ensure that the internationals feel so at home in Geneva that they never want to leave – and that the Genevans can no longer imagine life without them.

*Journalist, author, and columnist for Le Temps. Her published works include Genève, histoire d’une vocation internationale (Zoé, 2010) and L’histoire suisse en un clin d’œil, (Zoé, 2006).