Eugenics and Scientific Racism (original) (raw)

Fact Sheet

Eugenics is an inaccurate theory linked to historical and present-day forms of discrimination, racism, ableism and colonialism. It has persisted in policies and beliefs around the world, including the United States.

The Big Picture:

- Eugenics is the scientifically inaccurate theory that humans can be improved through selective breeding of populations.

- Eugenicists believed in a prejudiced and incorrect understanding of Mendelian genetics that claimed abstract human qualities (e.g., intelligence and social behaviors) were inherited in a simple fashion. Similarly, they believed complex diseases and disorders were solely the outcome of genetic inheritance.

- The implementation of eugenics practices has caused widespread harm, particularly to populations that are being marginalized.

- Eugenics is not a fringe movement. Starting in the late 1800s, leaders and intellectuals worldwide perpetuated eugenic beliefs and policies based on common racist and xenophobic attitudes. Many of these beliefs and policies still exist in the United States.

- The genomics communities continue to work to scientifically debunk eugenic myths and combat modern-day manifestations of eugenics and scientific racism, particularly as they affect people of color, people with disabilities and LGBTQ+ individuals.

What are eugenics and scientific racism?

Eugenics is the scientifically erroneous and immoral theory of “racial improvement” and “planned breeding,” which gained popularity during the early 20th century. Eugenicists worldwide believed that they could perfect human beings and eliminate so-called social ills through genetics and heredity. They believed the use of methods such as involuntary sterilization, segregation and social exclusion would rid society of individuals deemed by them to be unfit.

Scientific racism is an ideology that appropriates the methods and legitimacy of science to argue for the superiority of white Europeans and the inferiority of non-white people whose social and economic status have been historically marginalized. Like eugenics, scientific racism grew out of:

- the misappropriation of revolutionary advances in medicine, anatomy and statistics during the 18th and 19th centuries.

- Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution through the mechanism of natural selection.

- Gregor Mendel’s laws of inheritance.

Eugenic theories and scientific racism drew support from contemporary xenophobia, antisemitism, sexism, colonialism and imperialism, as well as justifications of slavery, particularly in the United States.

How did eugenics begin?

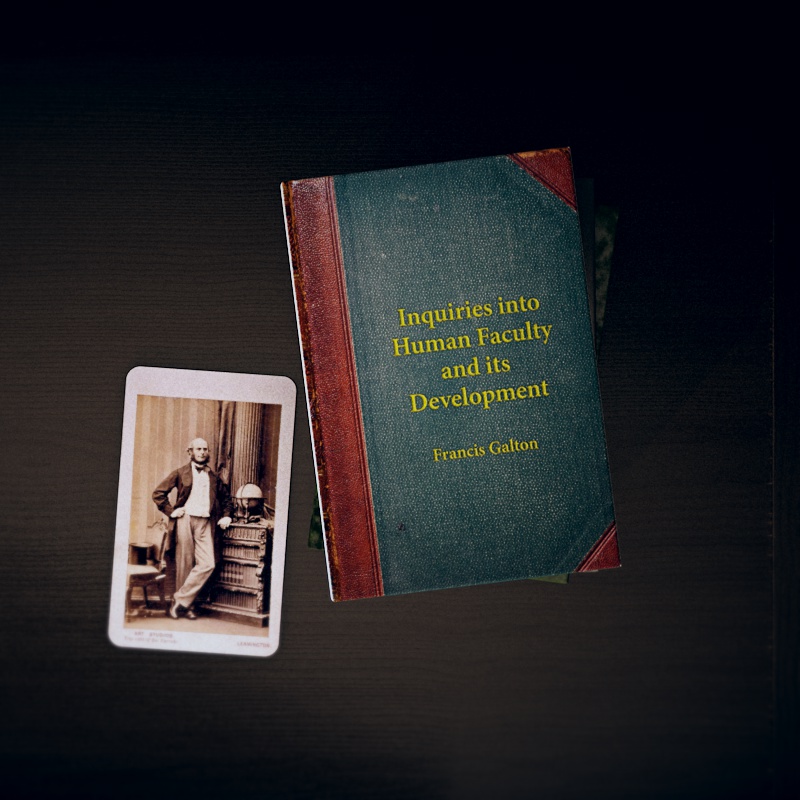

Francis Galton, an English statistician, demographer and ethnologist (and cousin of Charles Darwin), coined the term “eugenics” in 1883.

Galton defined eugenics as “the study of agencies under social control that may improve or impair the racial qualities of future generations either physically or mentally.” Galton claimed that health and disease, as well as social and intellectual characteristics, were based upon heredity and the concept of race.

During the 1870s and 1880s, discussions of “human improvement” and the ideology of scientific racism became increasingly common. So-called experts determined individuals and groups of people to be either superior or inferior. They believed biological and behavioral characteristics were fixed and unchangeable, and placed individuals, populations and nations inside of that hierarchy.

What did eugenics look like across the globe?

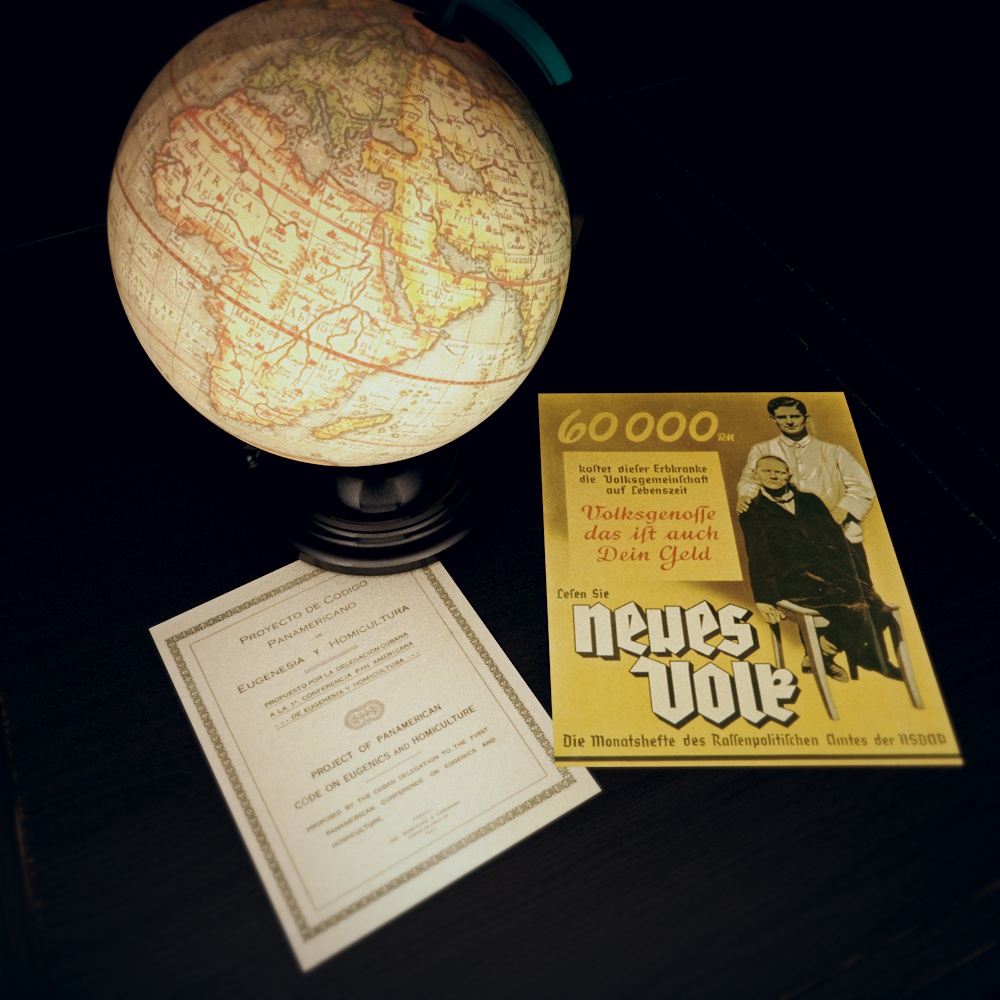

By the 1920s, eugenics had become a global movement. There was popular, elite and governmental support for eugenics in Germany, the United States, Great Britain, Italy, Mexico, Canada and other countries. Statisticians, economists, anthropologists, sociologists, social reformers, geneticists, public health officials and members of the general public supported eugenics through a variety of academic and popular literature.

The most well-known application of eugenics occurred in Nazi Germany in the lead up to World War II and the Holocaust. The Nazi German racial state between 1933 and 1945 used its resources to “cleanse” the German people and the Nazi state of those they deemed “unworthy of life.” Nazis in Germany, Austria and other occupied territories euthanized at least 70,000 adults and 5,200 children. They implemented a campaign of forced sterilization that claimed at least 400,000 victims. This culminated in the near destruction of the Jewish people, as well as an effort to eliminate other marginalized ethnic minorities, such as the Sinti and Roma, individuals with disabilities and LGBTQ+ people.

What did eugenics look like in the United States?

In the United States, slavery and its legacies, fears of “miscegenation” and eugenics were deeply connected in the early 20th century. Prominent American eugenicists expounded on their concerns of “race suicide,” or the increasingly differential birthrates between immigrants and non-Nordic races compared to native-born Nordic whites. Eugenicists used these concerns to promote discriminatory policies like anti-immigration and sterilization.

American eugenicists from a variety of disciplines declared certain individuals unfit, “feebleminded” or anti-social, which resulted in the involuntary sterilization of at least 60,000 people through 30 states’ laws by the 1970s.

These eugenicists disproportionately targeted Latinxs, Native Americans, African Americans, poor whites and people with disabilities during the entirety of the 20th century. Eugenicists were also crucial to the enactment of discriminatory immigration legislation that was passed in 1924 (the Johnson-Reed Act), which completely excluded immigrants from Asia.

Do eugenics and scientific racism still exist?

Yes.

While eugenics movements especially flourished during the three decades before the end of World War II, eugenics practices such as involuntary sterilization, forced institutionalization, social ostracization and stigma were common in many states until at least the 1970s and, in some instances, have continued into the present in various forms.

With the completion of the Human Genome Project (HGP) and, more recently, advances in genomic screening technologies, there is some concern about whether generating an increasing amount of genomic information in the prenatal setting would lead to new societal pressures to terminate pregnancies where the fetus is at heightened risk for genetic disorders, such as Down Syndrome and spina bifida.

The emergence of statistical techniques, such as polygenic risk scores, that can estimate risks for more genetically complex disorders have raised concerns among ethicists that their use in the context of in vitro fertilization and preimplantation genetic diagnoses. The possible genomic-based screening of embryos for behavioral, psychosocial and/or intellectual traits would be reminiscent of the history of eugenics in its attempt to eliminate certain individuals.

Some geneticists view both genomic screening and genetic counseling as an extension of eugenics.

What is NHGRI doing to address eugenics and scientific racism?

When the HGP began in 1990, there was widespread concern that genomics would lead to a new era of eugenics. Many bioethicists were aware of how past eugenic movements used genetic information to ostracize historically marginalized groups and believed that people would use the outcomes of the HGP and subsequent developments in genomics to further marginalize and stigmatize certain groups. People were also concerned that the HGP would usher in a new era of behavior genetics, where genes would be used to explain certain behaviors. Many discussions about the HGP revolved around whether employers or insurance companies could use genomic information to discriminate against specific individuals.

In response to these and other concerns, the National Center for Human Genome Research (now the National Human Genome Research Institute, or NHGRI) founded the Ethical, Legal and Societal Implications (ELSI) Research Program. For more than three decades, the NHGRI ELSI Research Program has funded research on all aspects of the social and ethical implications of genomics, including the legacies of eugenics and scientific racism in the context of new and emerging genetic and genomic technologies.

Building on a long tradition of these legacies, NHGRI is committed to taking proactive steps to provide leadership in the field of genomics in addressing structural racism and anything that would foster eugenics-based ideas. Together with efforts of the National Institute of Health, including the UNITE Initiative, NHGRI will continue to combat the legacies of eugenics and scientific racism and their present-day manifestations to develop an inclusive and welcoming genomics community.

In addition, the NHGRI History of Genomics Program is committed to interrogating the legacies of eugenics and scientific racism to further develop ethical and equitable uses of genomics.

Only by understanding and fully engaging with the history of eugenics and scientific racism will genomics serve to facilitate an inclusive and humane future.

Additional Resources

To learn more about eugenics and scientific racism, see the following resources:

Last updated: May 18, 2022