How the Dust Bowl Made Americans Refugees in Their Own Country (original) (raw)

Eight decades ago, hordes of migrants poured into California in search of a place to live and work. But those refugees weren’t from other countries. They were Americans and former inhabitants of the Great Plains and the Midwest who had lost their homes and livelihoods in the Dust Bowl.

Years of severe drought had ravaged millions of acres of farmland. Many migrants were enticed by flyers advertising jobs picking crops, according to the Library of Congress. And even though they were American-born, the Dust Bowl migrants still were viewed as intruders by many in California, who saw them as competing with longtime residents for work, which was hard to come by during the Great Depression. Others considered them parasites who would depend on government relief.

As many of the migrants languished in poverty in camps on the outskirts of California communities, some locals warned that the newcomers would spread disease and crime. They advocated harsh measures to keep migrants out or send them back home.

Migrants Fled Widespread Drought in Midwest

The Dust Bowl that forced many families on the road wasn’t just caused by winds lifting the topsoil. Severe drought was widespread in the mid-1930s, says James N. Gregory, a history professor at the University of Washington and author of the book American Exodus: The Dust Bowl Migration and Okie Culture in California.

“Farm communities in the larger region were also hurt by falling cotton prices. All of this contributed to what has become known as the Dust Bowl migration,” Gregory says.

The exact number of Dust Bowl refugees remains a matter of controversy, but by some estimates, as many as 400,000 migrants headed west to California during the 1930s, according to Christy Gavin and Garth Milam, writing in California State University, Bakersfield’s Dust Bowl Migration Archives.

Dust Bowl migrants squeezed into trucks and jalopies—beat-up old cars—laden with their meager possessions and headed west, many taking the old U.S. Highway 66.

“Dad bought a truck to bring what we could,” recalled one former migrant, Byrd Monford Morgan, in a 1981 oral history interview. “There were fifteen people to ride out in this truck, in addition to what we could haul”—including the family’s kitchen table, sewing machines, sacks to use in picking cotton, and five-gallon cans packed with cookies baked by Morgan’s stepmother. Along the way, the family camped out by the side of the highway.

When the family got to California, they stopped at farms and asked if they needed workers, and picked everything from tomatoes to grapes, Morgan said.

More people from the drought-ravaged plains actually settled in the Los Angeles area than in the San Joaquin Valley and other agricultural areas in California, according to Gregory. But migrants made up a bigger percentage of the population in the state's rural areas, and it was there that journalists recorded the dire poverty and desperation that John Steinbeck described in his 1939 novel The Grapes of Wrath.

In the mid-1930s, the Farm Security Administration’s Resettlement Administration hired photographers to document the work done by the agency. Some of the most powerful images were captured by photographer Dorothea Lange. Lange took this photo in New Mexico in 1935, noting, “It was conditions of this sort which forced many farmers to abandon the area.”

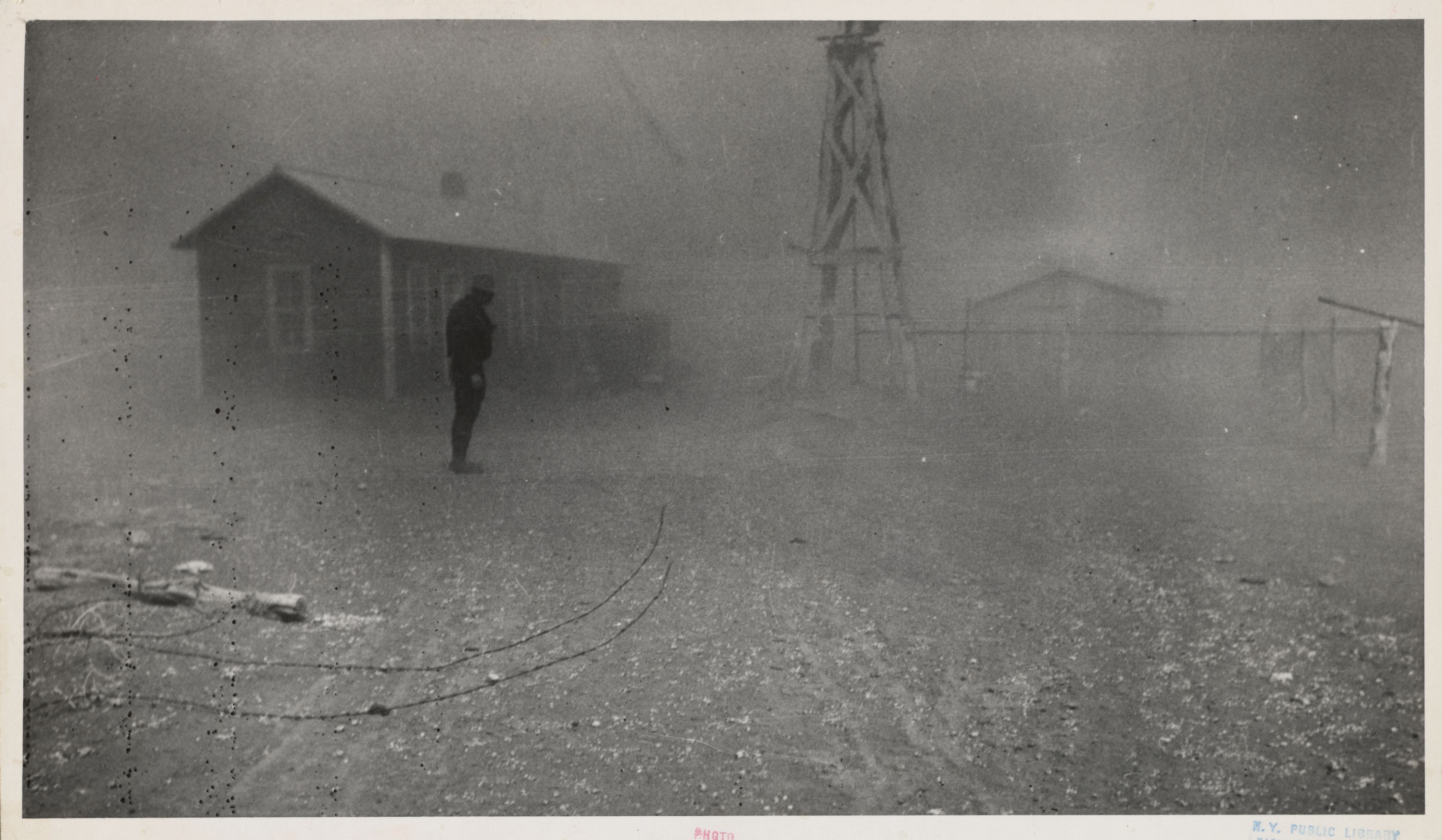

Arthur Rothstein was one of the first photographers to join the Farm Security Administration. His most noteworthy contribution during his five years with FSA may have been this photograph, showing a (supposedly posed) farmer walking in the face of a dust storm with his sons in Oklahoma, 1936.

Oklahoma dust bowl refugees reach San Fernando, California in their overloaded vehicle in this 1935 FSA photo by Lange.

Migrants from Texas, Oklahoma, Missouri, Arkansas and Mexico pick carrots on a California farm in 1937. A caption with Lange's image reads, "We come from all states and we can't make a dollar in this field noways. Working from seven in the morning until twelve noon, we earn an average of thirty-five cents."

This Texas tenant farmer brought his family to Marysville, California in 1935. He shared his story with photographer Lange, saying, "1927 made $7000 in cotton. 1928 broke even. 1929 went in the hole. 1930 went in still deeper. 1931 lost everything. 1932 hit the road."

A family of 22 set up camp alongside the highway in Bakersfield, California in 1935. The family told Lange they were without shelter, without water and were looking for work on cotton farms.

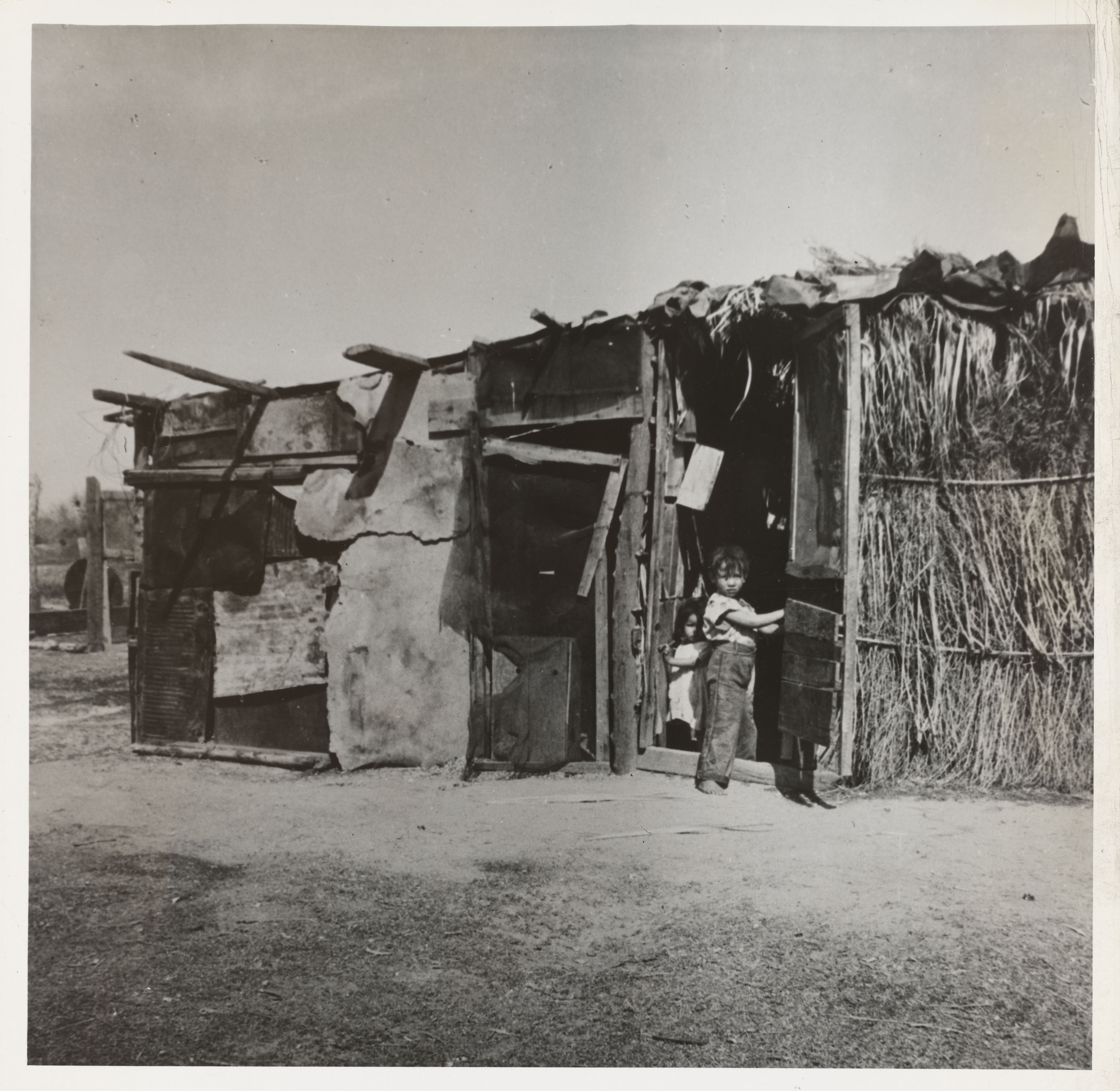

A pea picker's makeshift home in Nipomo, California, 1936. Lange noted on the back of this photograph, "The condition of these people warrant resettlement camps for migrant agricultural workers."

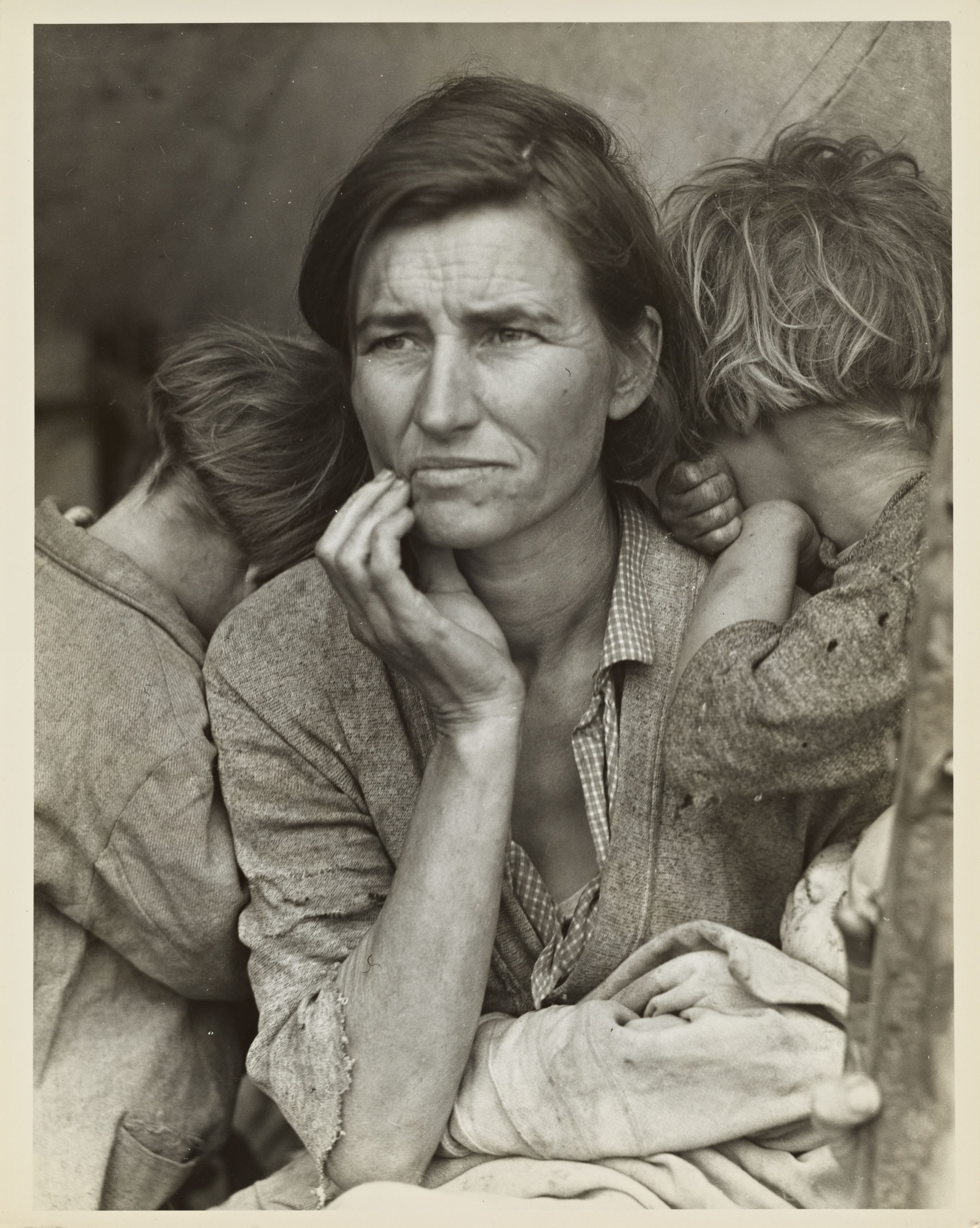

Among Dorothea Lange's most iconic photos was of this woman in Nipomo, California in 1936. As a mother of seven at age 32, she worked as a pea picker to support her family.

The family who lived in this make-shift home, photographed in Coachella Valley, California in 1935, picked dates on a farm.

Californians derided the newcomers as “hillbillies,” “fruit tramps” and other names, but “Okie”—a term applied to migrants regardless of what state they came from—was the one that seemed to stick. The beginning of World War II would finally turn migrants' fortunes as many headed to cities to work in factories as part of the war effort.

1 / 10: Dorothea Lange/Farm Security Administration

Police Officers Tried to Block Migrants at the Border

As the migrants’ numbers swelled, efforts were made to thwart the migration. Police officers sometimes met migrants at the state line and told them to go away, because there was no work, in what was called the “bum blockade.” Officers stopped one mother with six children at a checkpoint and demanded that she pay 3foraCaliforniadriver’slicense,thoughtheyrelentedwhenshesaidthatsheonlyhad3 for a California driver’s license, though they relented when she said that she only had 3foraCaliforniadriver’slicense,thoughtheyrelentedwhenshesaidthatsheonlyhad3.40 to her name and needed that money to buy food for her family, according to a L.A. Times account.

Those who got into California often found themselves continually on the move from farm field to farm field in search of work. They lived in spartan quarters provided by agricultural growers or squatted in “Hooverville” shanties on the outskirts of towns, before the federal government started setting up migrant camps to accommodate them, according to the U.S. National Archives.

“Yes, we ramble and we roam, and the highway that’s our home,” folk singer Woody Guthrie sang in “Dust Bowl Refugee.”

Californians derided the newcomers as “hillbillies,” “fruit tramps” and other names, but “Okie”—a term applied to migrants regardless of what state they came from—was the one that seemed to stick, according to historian Michael L. Cooper’s account in Dust to Eat: Drought and Depression in the 1930s. One California businessman described the newcomers as “ignorant, filthy people,” who should not “think they’re as good as the next man.”

Some warned that the newcomers would sponge off the government, although relatively few of them actually sought benefits, as State Relief Administration director Harold Pomeroy explained in a 1937 Desert Sun article.

Migrants Were Feared as a Health Threat

A local official in Madera, California complained in 1938 that the migrants crowded into the camps presented a health threat, noting that “these conditions are not to be blamed o the growers, but on the people themselves, [for] having lived in squalor for many generations” back in their home states. One riverbank shantytown that was home to 1,500 migrants was burned to the ground by disease-fearing Californians in 1936.

Ironically, it would be a war—World War II—that would finally boost migrants’ fortunes. Many families left farm fields to move to Los Angeles or the San Francisco Bay area, where they found work in shipyards and aircraft factories that were gearing up to supply the war effort.

By 1950, only about 25 percent of the original Dust Bowl migrants were still working the fields. As the the former migrants became more prosperous, they blended into the California population.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details: Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us