Notes Toward a New Romanticism (original) (raw)

I made a flippant remark a few months ago. It was almost a joke.

But then I started taking it seriously.

I said that technocracy had grown so oppressive and manipulative it would spur a backlash. And that our rebellion might resemble the Romanticist movement of the early 1800s.

We need a new Romanticism, I quipped. And we will probably get one.

A new Romanticism? Could that really happen? That seems so unlikely.

Even I didn’t take this seriously (at first). I was just joking. But during the subsequent weeks and months, I kept thinking about my half-serious claim.

I realized that, the more I looked at what happened circa 1800, the more it reminded me of our current malaise.

- Rationalist and algorithmic models were dominating every sphere of life at that midpoint in the Industrial Revolution—and people started resisting the forces of progress.

- Companies grew more powerful, promising productivity and prosperity. But Blake called them “dark Satanic mills” and Luddites started burning down factories—a drastic and futile step, almost the equivalent of throwing away your smartphone.

- Even as science and technology produced amazing results, dysfunctional behaviors sprang up everywhere. The pathbreaking literary works from the late 1700s reveal the dark side of the pervasive techno-optimism—Goethe’s novel about Werther’s suicide, the Marquis de Sade’s nasty stories, and all those gloomy Gothic novels. What happened to the Enlightenment?

- As the new century dawned, the creative class (as we would call it today) increasingly attacked rationalist currents that had somehow morphed into violent, intrusive forces in their lives—an 180 degree shift in the culture. For Blake and others, the name Newton became a term of abuse.

- Artists, especially poets and musicians, took the lead in this revolt. They celebrated human feeling and emotional attachments—embracing them as more trustworthy, more flexible, more desirable than technology, profits, and cold calculation.

That’s the world, circa 1800.

The new paradigm shocked Europe when it started to spread. Cultural elites had just assumed that science and reason would control everything in the future. But that wasn’t how it played out.

Resemblances with the current moment are not hard to see.

“Imagine a growing sense that algorithmic and mechanistic thinking has become too oppressive. Imagine if people started resisting technology. Imagine a revolt against STEM’s dominance. Imagine people deciding that the good life starts with NOT learning how to code.”

These considerations led me, about nine months ago, to conduct a deep dive into the history of the Romanticist movement. I wanted to see what the historical evidence told me.

I’ve devoted hours every day to this—reading stacks of books, both primary and secondary sources, on the subject. I’ve supplemented it with a music listening program and a study of visual art from the era.

What’s my goal? I’m still not entirely sure.

Luddites destroying a factory

I might write an essay on this in the future. Frankly, the subject deserves a book. But I doubt that I’m ready to take on that workload. Right now, I’m just trying to clarify my own thinking on this matter—because I believe it’s highly relevant to our current situation.

Today I will take a baby step, and share some of my random notes on the early days of Romanticism.

I’m now structuring my research in chronological order—that’s a method I often use in addressing big topics.

I make no great promises for what I share below. These are just notes on what happened in Western culture from 1800 to 1804—listed year-by-year.

Sharing these is part of my process. I expect this will generate useful feedback, and guide me on the next phase of this project.

As I’ve written elsewhere, I put a lot of energy into note-taking—so this may also be of interest to readers who have asked about my research methods. Consider the notes below as typical of the material I write for my own benefit, but rarely publish.

Because music is always my entry point into cultural changes, it plays a key role here in how I analyze past (and present) events. I firmly believe that music is an early indicator of social change. The notes below are offered as evidence in support of that view.

Napoleon attends a performance of Haydn’s The Creation in Paris on Christmas Eve 1800—but narrowly avoids a bomb (200 pounds of gun powder and stone fragments hidden in a wine barrel) on his way to the concert.

Romanticism is dangerous stuff.

Haydn publishes The Creation in 1800—a milestone moment for those (like me) fascinated by artists who grow bolder in their 60s and 70s. But the modernism here goes beyond the music. Haydn leaves church patronage behind, and performs his hot new work for ticket holders at Covent Garden and elsewhere.

Yes, we still praise the glory of God’s creation, but from now on worshipful audiences will pay tithes to the composer.

The ideology of British pop culture starts at this moment.

Wordsworth announces its arrival in the new edition of his Lyrical Ballads (1800), inserting a flaming manifesto as preface. He mocks previous writers for their elitism, and insists that the language of the common people is more artistic—from now on poets should focus on “incidents and situations from common life ... in a selection of language really used by men.”

This radical populism was already shaking up Germany, largely due to Herder—who did more than anyone in history to legitimize folk music and folk art. But now Wordsworth launches a missile at Oxford and Cambridge, hoping to replace their erudition and ornate language with rustic strains.

Wordsworth and Coleridge have just hung an albatross on the neck of British cultural elites. From this moment forward, hand-wringing over populist aesthetics will be the crisis that never ends in the Western world.

The irony is that the poems in Lyrical Ballads, most famously “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner,” don’t sound anything like the common speech of the masses. But they do resemble folk ballads in their embrace of rhythmic storytelling and supernatural elements.

The same thing had happened in Germany, where Herder relied primarily on folk songs to define populist culture. For the first time in history, music becomes the accepted measuring stick for authenticity.

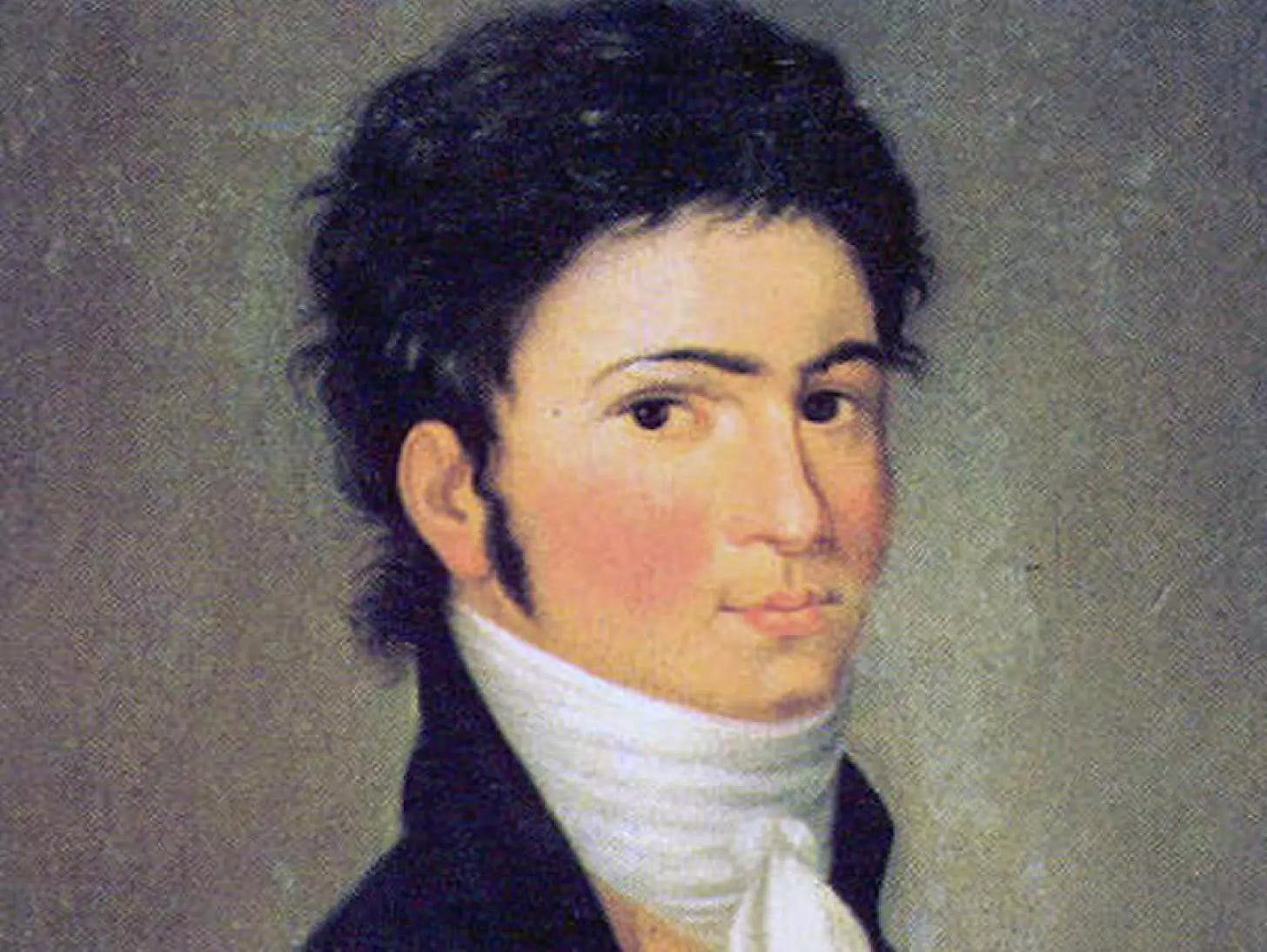

Beethoven turns thirty, and this is much more than a symbolic coming of age. Over the next three years, Beethoven invents an entirely new emotional vocabulary for Western music—you can already hear it in the two piano sonatas composed in 1800—the B-flat Major Sonata, Op. 22 (which he considered the best of his early works) and especially the Sonata in A-flat Major, Op. 26.

The latter is the only Beethoven piano work that Chopin performed regularly—and for good reason. The seeds of all future Romanticist piano styles, from classical to cocktail, are sown here. Even sonata form gets thrown out the window, and Beethoven reaches for extreme effects, notably the funeral march of the third movement, which would be performed at the composer’s own burial procession.

This is also the year of his first symphony and the third piano concerto—works full of anticipatory rebellion. You feel the beast trying to break out of the cage. The bars are already starting to shake, and will soon give way.

Beethoven at age 30

Schelling publishes System of Transcendental Idealism (1800) in Germany—and solves every problem in philosophy with music and art.

I’m not exaggerating. In Schelling’s brave new worldview, art heals the divide between objectivity and subjectivity, the inner life and outer world, philosophy and science, etc.

This book is seldom read nowadays, but it decisively shaped Hegel’s philosophy, and even contributes to some degree towards Marx’s. But I’m most struck by Schelling’s concept of the unconscious, which veers surprisingly close to Jung.

The unconscious here isn’t something to fear. It is now the source of freedom. The Enlightenment is officially over.

The Marquis de Sade, now in his 60s and approaching the end of his literary career, gets arrested (again) and held without a trial. In contrast to his public image nowadays, Sade was very much a figure of the Age of Reason, a time that (like our own algorithmic era) unleashed all sorts of dark energies and extreme behaviors seemingly at odds with the official progressive ideology.

But Sade’s fantasies didn’t seem so brutal after rationalism morphed into the Reign of Terror (which almost killed the author himself). In the waning days of the Enlightenment, fact became bloodier than the bloodiest fiction.

In stark contrast to the Sade novels of 1785-1800, the most characteristic literature of the first two decades of this new century will be gentle works celebrating nature, love, starry nights, and a more authentic life in the country.

Keep that in mind if you’re ever asked to choose between living with Rationalists or Romanticists.

Novalis dies in Germany, a few months after publishing his extravagant Hymns to the Night, which plays a key role in creating the noir aesthetic. Darkness will never be more fashionable than at this moment in time.

The first step, it seems, in countering rationalism, is to remove the light from the Enlightenment. So we will now see an avalanche of poems about sleep, dreams, nightingales, stars and moon, as well as the dark recesses of the inner life.

Idea for a digital humanities project: Do a statistical measure of poems, and chart how often they mention light versus dark—trace how this shifted from the end of the medieval era (with its neo-Platonic and Dantesque celebrations of luminescence) through to the current day.

My hypothesis is that we are moving right now from an aesthetics of light to an aesthetics of dark. When rationalistic and algorithmic tyranny grows too extreme, art returns to the darkness of the unconscious life—and perhaps of the womb.

Removing light from the Enlightenment—the paintings of Caspar David Friedrich (1774-1840)

Beethoven is just 31—but is contemplating suicide because of the rapid onset of deafness.

The first symptoms appeared in 1798, but now they’ve grown much worse. Beethoven moves to the countryside town of Heiligenstadt, hoping that the relative quiet will restore his hearing—but also to avoid social contact.

“For me there can be no relaxation with my fellow men, no refined conversations, no mutual exchange of ideas,” he explains in a letter of October 6, 1802. “I must live almost alone, like one who has been banished.”

His music grows more imperious and insistent during this whole period. A few months earlier, Beethoven was still imitating Haydn, Mozart, and C.P.E. Bach. But now he constantly breaks new ground.

I still find it hard to grasp how his music advanced more radically after the onset of deafness. There must be a lesson in that.

In 1802, Haydn starts referring to himself as a “priest of this sacred art.” This is a man who launched his career as a servant in livery serving the Esterhazy family, taking orders from the boss every day at noon.

Great composers are no longer servants. They now receive more acclaim than scientists or captains of industry.

In 1802, Ann Radcliffe writes a spirited defense of terror as a literary device. But she won’t publish "On the Supernatural in Poetry" during her lifetime. Finally in 1826, three years after her death, this pioneering attempt to legitimize dark populist storytelling shows up in print—but by then, supernatural elements are everywhere in European culture.

If you didn’t know that the Age of Reason had ended by that late stage, you merely had to read some novels published in the interim—Frankenstein, for example where the scientist is morally culpable, and monsters earn our sympathy.

Haydn is now so ill that he stops composing. Beethoven works on the Eroica.

Has there ever been a composer operating so far ahead of peers and rivals? Nobody in the world, circa 1803, has even started to assimilate what Beethoven is doing. Who are his leading competitors after Haydn steps aside? Hummel or Weber? Salieri or Cherubini?

Paganini is just 21, Rossini is only 11. Schubert is 6. Chopin and Mendelssohn haven’t even been born. Beethoven shows the way, but more than a decade will elapse before the musical establishment can even begin to gauge his larger impact.

The first use of the phrase “art for art’s sake” dates from this year—it quickly spreads all over Europe.

This is more than a defense of the creative spirit. It’s also a rebuttal to scientism and its pretensions as the ultimate ruler of human destiny.

Beethoven turns against Napoleon—and this is emblematic of the aesthetic reversal sweeping through Europe. Not long ago, Beethoven and other artists looked to French rationalism as a harbinger of a new age of freedom and individual flourishing. But this entire progress-obsessed ideology is unraveling.

It’s somehow fitting that music takes the lead role in deconstructing a tyrannical rationalism, and proposing a more human alternative.

Could that happen again?

- Imagine a growing sense that algorithmic and mechanistic thinking has become too oppressive.

- Imagine if people started resisting technology as a malicious form of control, and not a pathway to liberation, empowerment, and human flourishing—soul-nurturing riches that must come from someplace deeper.

- Imagine a revolt against STEM’s dominance and dictatorship over all other fields?

- Imagine people deciding that the good life starts with NOT learning how to code.

If that happened now, wouldn’t music stand out as the pathway? What could possibly be more opposed to brutal rationalism running out of control than a song?

But what does that kind of music sound like? In 1800, it was Beethoven. And today?