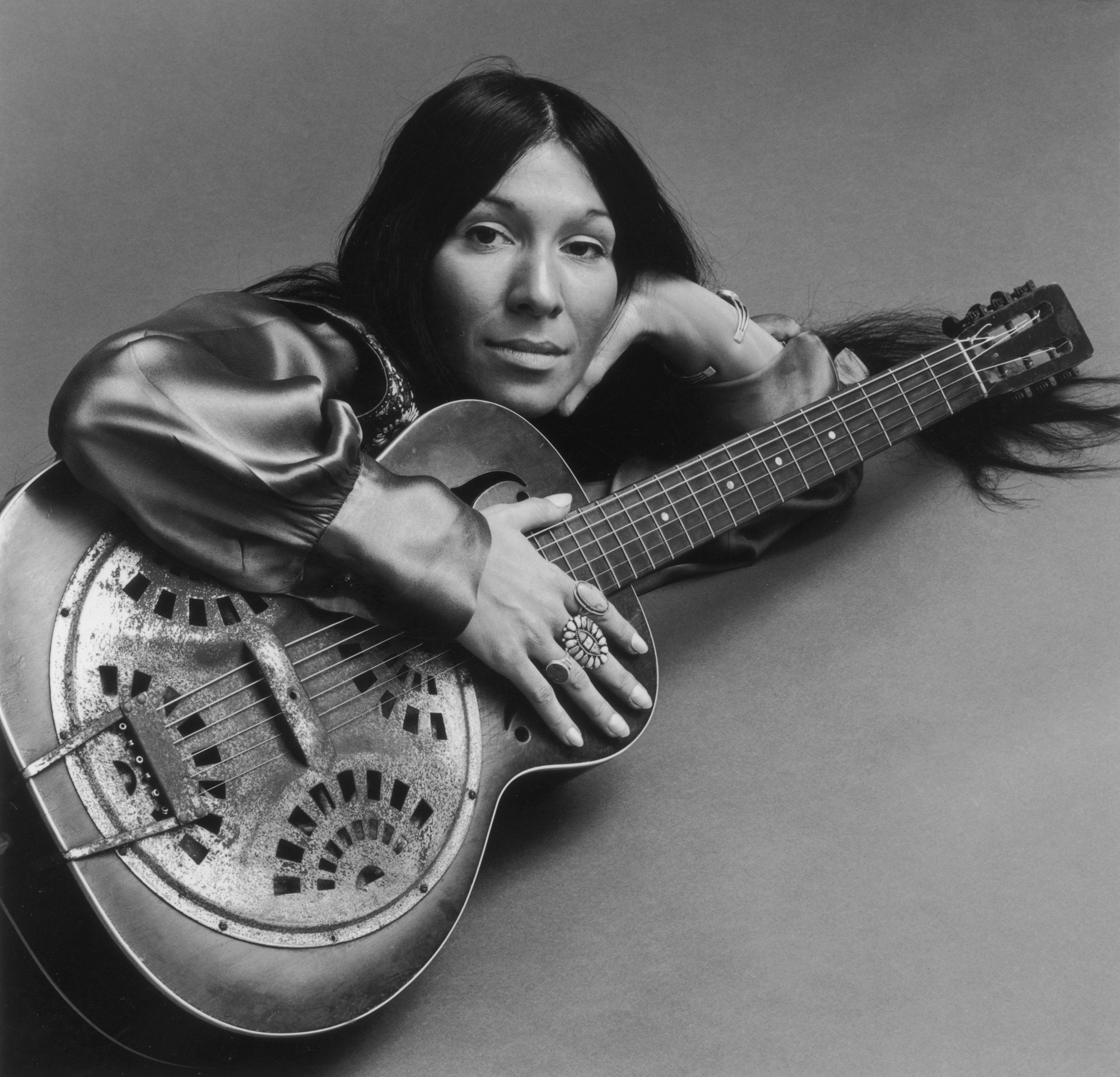

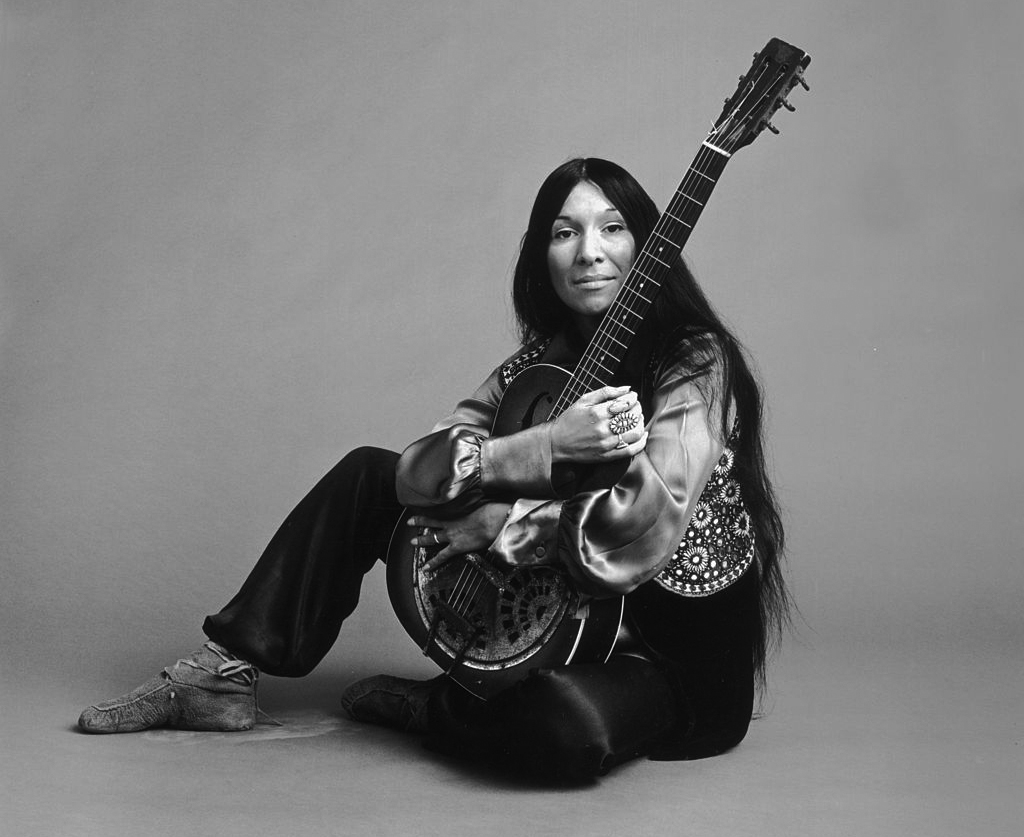

Buffy Sainte-Marie - Resilient Integrity (original) (raw)

Resilient Integrity

by Anil Prasad

Copyright © 2021 Anil Prasad.

Photo: Matt Barnes

Photo: Matt Barnes

Buffy Sainte-Marie’s contributions to the worlds of music and activism are critical and profound. Across her seven-decade career, the singer-songwriter, composer and multi-instrumentalist has made generations think deeply about and reassess their perspectives on the problems faced by Indigenous peoples of the Americas. She's also a vocal critic of racism, misogyny, political corruption, cronyism, and war mongering and profiteering in her work.

Her creative spirit has remained restless and forward-looking throughout her 18 albums to date, incorporating folk, rock, country, Indigenous, electronic, and experimental influences. Her most recent recordings, 2015’s Power in the Blood and 2017’s Medicine Songs, are among her most powerful and seeking to date, incorporating the latest production approaches to fuel her visionary and mercurial songs. The latter album finds Sainte-Marie revisiting some of her most well-known work such as “Universal Soldier,” “My Country ‘Tis of Thy People You’re Dying” and “Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee.” It also includes two new tracks, “The War Racket,” a searing indictment of the military-industrial complex, and "You Got to Run," which is designed to spur people into positive action.

She’s amassed countless accolades throughout her career, including a dozen honorary doctorates from prestigious North American educational institutions. Sainte-Marie also won an Oscar and Golden Globe for her 1983 hit single “Up Where We Belong” from An Officer and a Gentleman. Juno, Gemini and Polaris awards are just a few of her other key music industry acknowledgements. In 1997, she was made an Officer of the Order of Canada and in 2010 she received the Governor General’s Performing Arts Award.

Sainte-Marie’s iconic status was further cemented by many appearances on Sesame Street during the ‘70s and ‘80s, serving as a key reminder of the importance and relevance of Indigenous peoples to its millions of child viewers. She was also the first person to ever breastfeed a child on television, during a 1977 Sesame Street episode.

While her global fan base stands resolutely with her, Sainte-Marie has endured severe political backlash for her uncompromising views on the treatment of Indigenous peoples, particularly in America. Presidents Lyndon B. Johnson and Richard Nixon, and FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover—all of whom were advocates of suppressing political speech and civil rights movements—went on campaigns to get her music blacklisted on radio stations during the late '60s and early '70s. Their efforts significantly curtailed Sainte-Marie’s ability to reach mainstream American audiences with her music until the '80s.

Sainte-Marie eventually broke through the political barriers and continues as a vital recording and touring artist. At age 79, her performances are infused with incredible energy, drive and inspiration. She’s accompanied by an accomplished band featuring drummer Michel Bruyere, guitarist Anthony King and bassist Mark Olexson that deliver the goods with precision and power.

“Working for Buffy has been an amazing experience,” said King. “Her natural ability to call people to action and inspire is unparalleled in my personal experience. Her message about calling out corporate greed really hits home for me. In addition, she has the ability to make everyone feel welcome and appreciated with the way she frames community and all nations.”

Olexson agrees that her multi-generational impact endures because of her timeless, resilient integrity.

“In the decades since Buffy started writing and performing her music, the world has changed dramatically, but her message has always stayed the same,” said Olexson. “Be good to yourself, be good to others and be good to the planet—a pretty simple recipe for a better world. It’s easy, common-sense stuff that we too easily forget. Thankfully, Buffy's still here to remind us.”

He also praises Sainte-Marie for the familial approach she takes with the band and her meticulous approach to performing.

“I’ve never worked with anyone that's treated me better,” said Olexson. “To me, she’s exactly the way I thought she would be when I watched her on TV as a child, wishing I could hang out with her and Big Bird on Sesame Street. She's sweet, kind, honest, insightful, clever, witty, energetic, and positive. She's 'mum' to us boys in the band and we love, respect and care about her as if we were blood relatives. If you're feeling sick on the road, she brings soup to your hotel room. Her enthusiasm and love of life is unmatched by anyone I've ever known and it's inspiring.

“As a band leader, she's very sharp and though you might think she's not listening or too caught up in the moment to notice, very little of what's happening on stage gets past her. She knows specifically what she wants to hear and still allows us some freedom to interpret, but the underlining rule is that the music should never get in the way of the message.”

Innerviews spoke to the ageless Sainte-Marie in person after a performance at San Francisco’s Herbst Theatre, on the phone and by email, yielding this in-depth conversation about her life and career.

Photo: Christie Goodwin

Photo: Christie Goodwin

We live in complex and challenging times. What’s your perspective on the value of music in this moment to create unity and heal political division?

I think music-plus-lyrics can do a lot–explain, portray, dramatize, fan the flames, extend opinions, encapsulate, and add to the public debate—the same as other writings of all kinds have always done.

But music alone can also do something quite different from oration, poetry and song lyrics, as anybody who appreciates the role of an orchestral movie score knows. Music can set up the impact of words and images like nothing else. The Nazis used Wagner's music to set up their whole crazy horror show which wasn't the fault of the music. Music is used for military marches and bloody hymns about “God being on our side.” Music about “this land is your land” isn’t new or rare. It has been used by imperialists, racists, politicians, civilians, and churches—all kinds of power-hungry folks. Is it effective? You bet.

Music that was first weaponized early on by churches and “royals” is part of political theatre, along with costumes, jewels, crowns, carriages, horses, processionals, dramatic narrative, publicity, and slogans. In the UK, at one time bagpipes were considered a weapon. And music's connection to show business and selling product is obvious, with or without a message.

So, can music motivate and even manipulate people? Certainly, yes. Consider jingles. They exist just to advertise candidates and sell more stuff. That's what commercial music is supposed to do, according to sellers. People have traditionally used music to carry memes and messages of all kinds, political and personal, and they still do.

But to many artists, selling music is not the first intention. We’re convinced of ideas. They're already in our heads, intrinsically, and we didn't make them up just to extract money or votes. We hope to share them for their intrinsic value, like hope and self-expression. Like Stewart Brand said, we feel like “the information wants to be free.” And for an actual artist, the ideas come out of our own actual lives. We're on nobody's clock. We aren’t writing commercial jingles for a paycheck. What we do is different from that. We write the songs for free but we feel the concepts are valuable beyond price. Some of them happen to reflect what everybody's thinking but nobody's saying, and audiences sometimes appreciate that. Songs like this can make a big difference. But times change, people relax and termites come back.

The US is once again festering with overt racism and misogyny. How do you contextualize the urgency of what you communicate against that backdrop?

I look at it less from the point of view of my own output, and listen more. Although I agree completely with your description, including the urgency implied, I know I can only do so much each day: try to stay awake and look for opportunities to be effective in providing antidotes. I actually see a lot of people taking on citizenship for the first time, although they seem royally pissed at having to step up and be a citizen. Some are beginning to understand the old saying that the price of democracy is vigilance.

You’ve experienced censorship in several contexts. Describe what those experiences revealed about the power structures that inform the music industry and how you were forced to adapt to that reality.

Although a few years ago not many people understood what I and others went through in order to have a career, now most everybody is waking up. The misogyny in show business is a very old story. So is racism. So is political misbehavior and the desire to control artistic "produce" like the showbiz sharks do. I don't think I'm that special in having experienced it. To tell the truth, in my opinion, show business was just one more power business invented in Europe in which traditionally men had been kept sexually repressed as part of religion, unless they worked for "the man" like a king, the church, banks or business, in which case a loyal soldier was rewarded with pussy, including the right to rape. The modern war version is called ethnic cleansing.

But here and now, businessmen in show business as I have witnessed it, do seem to expect penile stimulation as well as money. It's always been one of the implied benefits. Not that everybody was a lecherous misogynist. Some were not. But it's definitely not a new issue. And if you walk away from one of them, you may find he will side against you when he gets a chance later. I discovered that the perils of not kissing his whatever might keep you safe, but down the road Mr. Piggy will not have forgotten that you declined to suck his ego. In my experience, the actresses expressing fear that he would either support or ruin them according to whether or not they "kissed the ring" are entirely believable.

Chuck D—someone who was also once monitored and tracked by the FBI for his politically-provocative perspectives—told me it’s now easier for the corporate media to simply ignore challenging and provocative artists rather than censor them. What do you make of his viewpoint?

Pretty right on. Thanks Chuck D. Termites on the exploit will find old holes and/or make new holes in your program. Better stay vigilant. On the other hand, in Europe, Australia and Canada I am often told that my songs have made a difference to lots of people. Less so in the US where I became background very early in my career.

Buffy Sainte-Marie, 1969 | Photo: Vanguard Records

Buffy Sainte-Marie, 1969 | Photo: Vanguard Records

Given that situation, how do you recommend artists circumvent the system to get their message out if the mainstream media won't cover what they say?

Well, you and I both know it's not easy, especially for somebody new. If you have a super manager discover you or something happens to you like A Star is Born, that's luck. Nobody can count on that. What I always tell artists is do things the old way. You’ve got to play everywhere and for everybody. You play every chance you get. You don't say no. If somebody invites you to play, you play. It's not about the money.

If you're Paul Simon and you come from a business family and you sit around at dinner and your uncle is a lawyer and your dad is in the music business and you have the phonebook, it's real easy to know what to do.

It's so competitive out there for white musicians. I mean the white music industry is huge—hundreds of thousands of people, right? The Black and Latino music industries, too. But at least those exist. We don’t have that. We don't have any people at record companies who want to help us along. It's a dilemma.

But for Aboriginal people or other marginalized people who aren’t well-connected—even people who are just from the boonies from out of town—if you don't have the address book, you don't even know where the door is, let alone how to get in, who to talk to or what to say once you get there. For Indigenous people or marginalized people in particular, what you got to do is to just play every place and build a niche base wherever you are. However, there's a however to that, too. I always tell new artists, "Sometimes, you have to get out of town," because I think there's a lot of bullying in small communities and families on reserves.

A lot of people have come down with a behavior pattern that originates with the residential schools, so they bully each other. If somebody tries to do something good, some bozo will try and cut you down. That's why I say it's really good to get out of town.

Another piece of advice is don't get mad at people because they don't know you yet. Whether you're trying to give them a piece of information or some music and art, they don't know who you are and what you have to give until you show them. That's what the show part of show business is about. You show up and you're showing something. Unfortunately, you find some musicians who get really excited the first time they hear that round of applause. That's where they stay for the rest of their careers. They never learn another chord. They just keep playing those same three chords over and over again and their songs sound like everybody else's songs over and over again.

I also had a hard time in the music industry because I didn’t drink. I didn't go out with the boys afterwards and hang around, make deals, network, or have a social life. I kept myself out of that just for girl safety reasons. I think that not being a part of the scene can be counterproductive. If you are a part of the scene, you've got something going. If you're Paul Simon or if David Geffen is handling your career, if you're part of the machine, you know everybody. If you don't know anybody, it's up to you. You just play as much as you can. You just play everywhere. It's not as though a record company will build a career for you. It goes the other way. You build a career and then a record company may be interested.

Most artists are not aware that that's actually the way it works. They keep waiting around for somebody to discover them. The fact that nobody discovered you yet is the perfect excuse to make new, more, better, different, more diverse, and more unique music.

Buffy Sainte-Marie, 1965 | Photo: Vanguard Records

Buffy Sainte-Marie, 1965 | Photo: Vanguard Records

What’s your perspective on the state of activism in popular music?

I think a lot of the activism of today is done online, through social networking of all kinds, at all levels, with and without bozos. It’s truthful and untruthful. It's just like the streets. I think the Internet takes the place of the streets right now. On the Indigenous front, there’s a lot of activism now.

Some musicians are shy to be outspoken these days. See, in the ‘60s it became hip. It wasn't hip to be outspoken when I started, but over the next four or five years, it became hip to at least seem like you're outspoken, right? There were people who would be outspoken about stuff they didn't believe and just heard. They just went with the crowd.

Another thing is, where are people like Paul Simon, Sting and Bob Dylan? Are they asleep? Do they not want to risk their precious legacies? Did they run out of energy? Are they afraid of getting blacklisted? Are they negatively advised by their businesspeople?

People told me I was crazy to do some of the things I did, but I’ve never held back on whatever I was going to write. People would tell me “Buffy shouldn’t sing that song because she’s supposed be like Woody Guthrie.” But no, I’ve never held back, so my catalog is super-diverse, but most people’s are not. Most people don’t cross genres, let alone being outspoken and saying something that’s strong.

I’ll never understand why other people hold back and prevent themselves from being everything they can be. I think it probably also goes back to their family, friends and social life. If you’re a rock and roller, you’re not supposed to be doing something else, including the activism part, because of the worry somebody might say something negative.

It's a great risk to put yourself out in this way. Not everybody has that type of courage. There are Clives and Davids, and Donalds and Nixons throughout show business and they can and will sink your boat if you seem like a threat to whatever they're trying to sell, be it music or ideas. To them it's "just business.” It's not your writing or singing that will threaten these guys—it's your success. So, as long as you're not succeeding, you're no threat. This makes artists afraid to rock the boat.

My position is that if you really do believe your work can make a difference in the lives of other people, polish it up to competitive level. Practice, practice, think, practice some more, and then give it your best shot. Play everywhere for everybody, for free or for pay, and build an audience. If you're building an audience, business people will notice. But sometimes it's best to get out of town to avoid the local trolls who've hated you since kindergarten. I advise college as the best safe space to grow.

I also feel that as a singer-songwriter, I'm trying to heal the world, not just poke it in the eye to get my name in the paper. If you're going to risk going up against traditional colonials in any endeavor with a three-minute song supporting change from business-as-usual, I advise compassion and a very sharp scalpel, sterilized with accuracy to the point of footnotes, and bulletproof with built-in answers. We need to build confidence in understanding new solutions, not just insult people who "don't get it.” Make a work of art that anybody can understand.

How does your recent song “You Got to Run” relate to that?

“You Got to Run” is written as a vitamin for somebody from the grassroots or otherwise marginalized place who feels like a nobody, but has the potential to do something great. It's about overcoming the trolls and actually accomplishing something. I meant for the title to fit a number of meanings. It could be about a marathon for cancer awareness in your community. It could be “You got to run... for office!” or “You got to run... your own life.” It has little medicines embedded into the lyrics, including the acknowledgement of bullies and trolls in our families and neighborhoods; feeling like a no-one until you bend and learn to be your own best friend; and knowing how and when to make your move in accordance with nature, so that it's actually effective, not just spinning wheels.

Tell me about how your collaboration with Tanya Tagaq on “You Got to Run” came about.

We liked each other and it was something we wanted to do. We didn’t know if we could. I don’t think I’d ever collaborated, previously. “Up Where We Belong” is a collaboration, but I had already written my part completely and never worked with the other two guys on the song. I wrote the melody. I usually tell people “I’ve never worked in an office. I’ve never been part of a band. I can lead, hire and pay a band, but that’s different than being in a band.” So, I didn’t think collaboration was up my alley.

Tanya and I met at the Folk on the Rocks festival in Yellowknife, maybe 20 years ago. She was just starting out. She was really young and I thought she was terrific. I’d see her from time to time, later. I really cautioned Tanya about alcohol, too. I always do, because I think it’s detrimental to people. I try not to be annoying, but when I see people who have a brilliant career in front of them, I caution them about shooting themselves in the foot because they can’t show up for their commitments. The number one rule of show business is “show up.” If you don’t show up, you don’t get anywhere.

So, years went by and then Tanya won a Polaris Prize. I had won one as well. Steve Jordan, the founder and director of Polaris, called me up and said, "We love it when our Polaris winners collaborate." I had already worked with Owen Pallett, who also won a Polaris prize a few years ago. I hired him to help me with a couple of symphony concerts, which were brilliant. I told Steve my obvious choice was Tanya. They called her up and asked her who she would like to work with, and she said “Buffy.” So, it was a no-brainer and was great.

The song was all written. All Tanya had to do was show up, sing and be herself. She didn’t have to learn my part or try to harmonize with what I was doing. Tanya is totally unique. There weren’t any rules. So, she showed up, we played around with the song, she let it rip and it came out wonderfully.

Buffy Sainte-Marie, 1968 | Photo: Vanguard Records

Buffy Sainte-Marie, 1968 | Photo: Vanguard Records

Describe the process of revisiting and reimagining your classic songs for Medicine Songs and Power in the Blood.

Power in the Blood had a lot of success. To follow it up, I saw an opportunity to do something I'd wanted to do for years in answer to questions often from activists and teachers as to “where can one find this song?” I wanted to make Medicine Songs. I wanted to record fresh versions of all my activist songs and put them on one album, because they just go together really well—both the protest songs and my other activist super-positive solution songs like “Carry It On” and “You Got to Run.” So, I told Geoff Kulawick, the owner of True North Records, that's what I wanted to do. But I had too many songs, so we made seven more available via a download sticker.

Some songs like “Now That the Buffalo’s Gone” and “Universal Soldier” still sound best acoustic, I think. Others I changed somewhat. Some I sang in a new key or used different instruments on. I just did each one as its own little movie, depending on how it sounded in my noggin today. I felt no loyalty or disloyalty in matching old versions.

Tell me about your creative process and how it has evolved over the decades.

Remember the ad for Almond Joy and Mounds bar that went “Sometimes you feel like a nut. Sometimes you don't?” Sometimes I know when a song is best presented with just guitar and voice. Sometimes I want more, like a symphony orchestra, powwow singers or a great pop producer. I try to match what I hear in my head.

I'm a singer-songwriter, which means I write songs mainly to perform myself. I'm going to walk them onstage, stand in a bright light and give them to whoever's there, take responsibility for what they say and how they affect people, so it's pretty personal. I'm going to "wear" the song for years to come, so I'd better love it and make it as good as I can. For Power in the Blood, first I created home demos for most of the songs, assembled them on a CD, sent the CDs to three producers, from a narrowed-down list of seven: Chris Birkett, Jon Levine and Michael Wojowoda. I asked each producer which ones he'd best like to produce. I chose to work with all three. We divided up the songs. Then I worked with each of the producers on his faves. I chose Michael to oversee the final mixing so that all these songs would technically work together on the same album with regard to loudness and other sonic issues.

There used to be some people in the music business who said I couldn't do all kinds of things that I was already doing, like using electronics, computers, Indian powwow, and pop. I guess my method has always been to listen to the song in my head, try to reproduce that, and if it needs more, either find somebody who can play it on standard instruments, or else try to create the sound some other way. I continually improvise and fiddle around blindly with sounds because usually that's where I find the missing links that I was seeking.

Make a list of your favorite singer-songwriters, and imagine any of us standing in front of a microphone in a strange place in a room full of strangers with the money clock ticking and other people telling you what to do—and then turning your music over to more strangers who choose ugly takes and ugly photos. That's how it was for a lot of us, and it sucked. Getting my own hands on the sound machines really extended my ability to create for a listener something unique and original the way I imagined it.

Stop thinking Pro Tools—I'm talking about the 1970s-1990s. In 1984, I got my first Macintosh—128k and I still have it. With the skills I already had and nobody to teach me, I was one happy artist. I also had an ARP, a Mellotron, a Continental Baroque, a Fairlight, and a Synclavier. I could turn my voice into a cello and then a coyote, which was kinda fun. I could also create textures, orchestral sounds and rhythm thingies that were inspirational to me as I was playing with them, and some of it wound up in a movie score or on a record. But much of that wasn't heard by the public because I was already persona non grata in the record business. Also, I took 16 years off to raise my son, and that was when I had the most time at home to experiment. It was really fun.

Once I had my own studio, it became easier because I wasn't on the record company's clock. My process kinda changed with the technology since I had electronics earlier than most other people. I could work in my own house any time, record things lots of different ways, and do multiple diverse saves. Also, when I'd go on the road, I could bring my work along on a floppy disk and continue in Toronto, New York or London. In 1990, when I was making Coincidence and Likely Stories, I used CompuServe to send digital files over the Internet from Hawaii to England to my co-producer Chris Birkett who also used CompuServe. It was the very first time the Web was used to deliver an album. It came out in 1992.

My process now is to keep from getting discouraged as “termites” invade the software, the hardware and the Internet itself.

Explore how you put together “The War Racket” for Medicine Songs, including how the song’s arrangement reflects the searing lyrics.

“Universal Soldier” made people wonder if I get discouraged that war is still happening after all these years when we thought we'd licked it after Vietnam, World War I or World War II. They were all supposed be wars to end all wars. The premise of individual responsibility for the world we live in that “Universal Soldier” implies is still true in my view, but you have to keep applying it, which pisses some people off. In my opinion, wars are like termites. They're cyclical, almost seasonal, and if you live in a wood house, you're gonna get termites, not because you're doing something wrong, but because that's what termites and war profiteers do. They eat wood. They launder money. Don't take it personally, but if you don't exercise vigilance, that's what happens.

“The War Racket” expands upon that idea. I recorded it two ways on Medicine Songs. For the bare "coffee house" acoustic version, it's just my voice and guitar, kinda old-man style. For the pop version, I tweaked a sound from the Roland Juno, added Chris Birkett's thunder sheet, and my guitar part from the acoustic recording, so it's real simple, although hugely strategic. No piano, bass and drums here. If you notice the third verse, the instruments and the vocal are pounding, insistent, loud and raging, but the final verse doesn't try to top that energy. Instead, it drops down to a rather sickening simplicity and it just lies there naked as a corpse. Although the song is intellectual, it's still primal.

Similarly, “Universal Soldier” surprised a lot of people because I do not resolve the final chord. I just left it hanging, very deliberately.

Buffy Sainte-Marie at The Newport Folk Festival, 1967 | Photo: Criterion Collection

Buffy Sainte-Marie at The Newport Folk Festival, 1967 | Photo: Criterion Collection

What are the biggest challenges you face during your creative process?

Trying to stay healthy while touring. Erratic sleep and erratic food at weird hours. Brain-dead in meetings. Wide awake at 5am. Jet lag. And interrupted creative time at home. Beware of success. It can rob you of that amateur intense focus time that success replaces with interviews, phone calls, manicures, publicity, deadlines, and distractions from the zone that comes about at more boring times.

Your recent music includes many contemporary influences both in terms of production and arrangement. Tell me about your drive to ensure your music remains infused with current sonic approaches.

It's funny, songs just pop into my head, and I hear them dressed in whatever style they originate. I don't try to be contemporary, but the relevancy is sometimes built into the original experience from which I'm drawing in my own life. I really am there and I actually do care. Metaphorically, I take snapshots of the world I'm in, which is always contemporary at the time, and this informs the backgrounds, the lighting, the emotion, mood, and other contextual elements that appear in the song, as they would in a photo. I don't have a plan to match a hit genre template in mind when the song first appears, although it might sound contemporary. I just live mostly in the same world as everybody else.

But your question also addresses sonic issues. Like most musicians, I play around with whatever makes noise: pots and pans, water drops, ethnic instruments, computer files, weather, sound effects, and old cassette tapes I have around—there's no hierarchy, just what I find interesting. Although I can be very strategic in refining a point lyrically, when it comes to inspiration and homemade music, it's really very kindergarten.

What were the biggest highlights and challenges of working with Vanguard Records during your nine years with them?

The highlight was realizing that I had a record contract, which was a big deal for me, as a record fan. The lowlight was that I had never met a lawyer previously. I don't come from a business family, so I didn't know what I was doing. When I went in to sign, Vanguard's guys asked who was my lawyer. I said “I didn't have one of those.” They said, "That's okay. You can use ours."

Eight albums later when I believed my contract was up, the man who ran their art department came to see me when I was in a hospital bed in New York, recovering from a stomach ailment. He showed me an unflattering photo where the hair was green and the face orange, and threatened that they would put out an album of outtakes with that photo and call it The Best of Buffy Sainte-Marie Volume II unless I re-signed with them. I didn't and they released it.

Buffy Sainte-Marie, 1969 | Photo: Vanguard Records

Buffy Sainte-Marie, 1969 | Photo: Vanguard Records

How do you look back at 1969’s Illuminations and what you accomplished with it?

It was fun! I had all these songs and the only thing they had in common was that each was a bit weird. I did each one of them "in character.” I had been looking at illuminated manuscripts from the Middle Ages and each story they portrayed was relevant only to itself and a certain philosophical overtone. “God Is Alive” was me ad libbing several pages of Leonard Cohen's novel Beautiful Losers with my guitar and voice, which when synthesized with Michael Czajkowski's Buchla became all kinds of ambient noises, sounds and sonic support.

Actually, what inspired Illuminations was the way I've liked—and continued to like—to make music from the time I was a child. I like lots of diversity, as if the whole album was part of a bigger statement. This wasn't popular at the time. Most albums would be a collection of similar songs in the same genre. But from childhood, I would make music on anything. In the rather limited world of the Kingston Trio, Pete Seeger and Woody Guthrie, there wasn't a lot of harmonic overtones being heard and not a lot of stretch from song to song, either in genre, style or message.

1974’s Buffy and 1975’s Changing Woman are among your many recorded highlights, but few know those albums. Reflect on making them.

I made those with Norbert Putnam after I had broken away from Vanguard and signed with MCA.

Buffy has “Sweet Little Vera” which is great. I performed that with Randy Bachman at the National Arts Center in Ottawa in 2018. I hadn’t done it for years. “Sweet, Fast Hooker Blues” is classic stuff. I love that whole album.

I feel the same way about Changing Woman. “Eagle Man/Changing Woman”—I love that. I’d been hanging around the Najavos and Apaches, and all that poetry came out of their prayer life. “Mongrel Pup?” Holy smokes. That was way before Eurythmics. I’m singing it in four different voices. I was screaming with one, whispering with another, singing one at normal volume, and fooling around with the fourth one. “The Beauty Way” has a strange, strange progression to it. “Nobody Will Ever Know It's Real But You” I co-write with Norbert. He came up with a beautiful melody and I put words to it. I think that’s the best vocal I ever did. “All Around the World?” Oh my god. That was written after I had been hanging around with movie stars like Bruce Lee. “A Man” is a very sexy song.

Tell me the tale of hanging out with Bruce Lee in 1972.

I was invited to do a concert in Hong Kong at The Lee Theatre, which has no relationship to Bruce. The guy who owns Golden Harvest Studio, Michael Hui, brought me over for a concert. I brought my mom with me. He gave us one-quarter of the entire top floor of The Mandarin Hotel. It was made into a suite the likes of which I’ve never seen before or since. It was beautiful.

Bruce Lee was filming Enter the Dragon when I was visiting and I went over to see him. Michael, the movie guy, brought me over. It was the day Bruce was filming the nunchuck scene, which he had been working on for three days, because they wanted to do it in one take. Bruce’s arms were all bruised and he was laughing about it.

Michael introduced me to Bruce and we spent some time hanging around in a hotel lobby. We didn’t fall in love. [laughs] He was terrific. I really admired him. So, that’s my Bruce Lee story.

One of your least-known albums is the Attla soundtrack you created with Will Ackerman back in 1985. Tell me how that came about and your interest in George Attla’s story.

I wrote and recorded everything, except Will's parts, in Los Angeles, with my friend Jill Fraser who built her own Serge instrument. I can't remember how the producers reached me initially but, having said no to a lot of movies, I said yes to this one because of the cast and the story. Lotsa Indians, and a true, precious story. I never met George, but I did meet Garrett Wright, his competition, whose wife Miranda is a friend via philanthropy.

Buffy Sainte-Marie and Anthony King, San Francisco, 2019 | Photo: Anil Prasad

Buffy Sainte-Marie and Anthony King, San Francisco, 2019 | Photo: Anil Prasad

It has become more difficult than ever for musicians to earn a living. What’s your view on the myriad changes that have occurred in the music industry in the last decade?

I've been in the music business for a long time and I've seen some pretty highfalutin bozos heading up record, management and movie companies, and calling the shots. They are just plain ruthless, politically vacant and misogynistic. I've seen a lot of nasty people in the music business and it took me a very long time to understand that the music business isn't really about music. It's really about business.

When I first got into show business, somebody said, "Yeah, these record companies, they don't care how good your songs are. They could be selling sneakers or tomatoes. All of you artists, you think it's about the quality of your work. No, it's all about the sale. All that matters is they sell." There's something to be said about that guy's honesty. The music industry is like any big industry that brings in money. It attracts a lot of sharks. They set it up for themselves and for their goals.

Now, people at the top are very, very greedy. They always have been in the music industry, but now the mindset is “take as much as you can get.” It’s bad leadership and they set an example for everyone else in the industry.

Touring is just about impossible for most of the artists I know. Everybody's gouging, because everybody's being gouged. It used to be I could live my life on the road—fly to England, do concerts on weekends and maybe one other during the week, and live and learn the rest of the time. Lots of artists did this. But now the airlines and hotels are so expensive. Try supporting five people in expensive hotels, rental cars and airplanes. The airlines see me coming with four musicians and 13 pieces of equipment and luggage, and they can charge a prohibitive amount of money. So, the only way we can afford to play is to do concerts every night which isn't good for musicians or the quality of music we bring. I’ll still be doing it, but will pull back. The last straw for me is that air travel is a huge pollutant, and I try to be as green as possible.

You bring more energy, drive and excitement than most musicians in their twenties do during your shows. What’s your secret for performing at this level at age 79?

Thank you for those nice words. I really appreciate it. I live a double life. There’s the lights-camera-action performance world you’ve seen me in. But then I really, really withdraw into a private life at a farm in Hawaii. I got rich and famous really young, when I was in my very early twenties. First, I bought a house in Maine. I then sold it and moved to Hawaii in the mid-‘60s and I’ve been there ever since.

I spend a lot of time outdoors and in the country, pretty much out of the rat race. I can do what I want. That’s a very, very lucky thing for any musician to be able to do. Usually, if you’re a working musician, because you have so much work, you don’t get any time to actually create.

When the public sees me perform, they think I’m creative. But when they’re not seeing me, they think “Oh, she retired. She died. She doesn’t have a hit.” But when they’re not seeing me, I’m doing things I would never have time to do when I’m touring. I’ve had a really interesting life. I took 16 years off in the middle of my career. I never expected to last in the first place.

I think to my benefit, I had a high level of recognition really quickly. Then the whole blacklisting thing happened and my music couldn’t be heard in the US anymore. I didn’t feel bad about it, because I didn’t have high expectations. I just figured singers come and singers go.

I think I’m reinforced with a genuine private life and time to myself. I always say I’m like an overgrown kindergarten kid in that I don’t seem to experience the pressure really hungry professionals experience. I suffer from jet lag, but I don’t suffer from writer’s block.

I’ll get a little more specific about why I feel as good as I do at age 79. Today, people think “Oh, how can you be like that at your age?” But they thought exactly the same thing when I was 21. They said “How can you be so wise when you’re so young?” Now, they say “How can you be so active when you’re so old?” There’s really no difference. I feel the same way I did during my first album.

I work out. I eat like a champion. The book Genius Foods is something people should read. It’ll give them a whole new boost on how you can survive in an era of overmarketing by food companies who taught our mothers to give up butter and feed us Crisco instead. A lot of parents have continued with the information their parents got when the food companies started hoodwinking us with the idea that we should eat what they provide instead of what nature provides.

I also do ballet. I do flamenco dance. It’s very private. I don’t do those things on stage. That’s my beautiful hobby. I think another big difference for me is I never got into alcohol. When I see my peers in a workout plan—people who are 10-20 years younger than I am—they’re obese, and fighting diabetes, cancer and heart disease. I really think I dodged the bullet when I never used alcohol. But it did impact my career. It’s not the way people expect you to act in show business if you’re trying to become a megastar. You don’t say no thanks to people’s wine, and I did.

Mark Olexson and Buffy Sainte-Marie, New York City, 2017

Mark Olexson and Buffy Sainte-Marie, New York City, 2017

Tell me about your current band and what makes its members special for you.

I first met Mark Olexson at a Gibson show in 2010. They asked me to come down. I was going to perform on guitar and keyboards. He was there and helped me set up my keyboard. We got to talking and he was terrific. He plays every instrument.

Four years after I first met Mark, I had a change of personnel in my band in 2014. Previously, I had an all-Aboriginal band from Winnipeg. My guitar player at the time, Jesse Green, fell in love, married his dream girl who got her dream job and he turned into Mr. Mom. All of a sudden, I didn’t have a guitar player. Then my bass player, Leroy Constant, ran for office and got elected Chief of his Cree reserve. So, now I’m short two musicians.

I remembered Mark and called him and said “Hey, do you remember me?” Turns out he was on an ocean liner doing a cruise gig when I called. Apparently, he was somehow abandoned by the cruise line and had to get to an East Coast gig. He was in the middle of dealing with that when we talked. So, after all those years, I connected with Mark and here he is. He turned out not only to be a fantastic bass player, but he also plays keyboards and computers. I tell him all the time he needs to make his own album.

The same is true for Anthony King. After Jesse left, I had a concert coming right up in Southern California. We auditioned Anthony. He knew every song. He was even dressing like our band. He was so perfect. He can play everything. He also reads music, which I can’t do. He’s not only a wonderful musician, but also a great hang.

Now, Michel Bruyere, our drummer, when I first met him, he had more experience than any of the guys in my previous all-Indigenous band. He had traveled, been to Europe and played in the group Eagle & Hawk. When I was looking to put that original Aboriginal band together, I auditioned 27 musicians. Michel was one of them and he keeps getting better and better. I’m very, very lucky to have Michel. He not only plays great, but I’ve seen him blossom into a person he should be really proud of. He really cares about his family and his health. He’s learned his language.

This is a really special band. We have a lot of fun. We’re good to each other. I couldn’t be happier.

Do you ever contemplate your legacy and the impact of your contributions to music and activism?

I do. I never thought I was going to last. Everything that comes up for me, I figured, “Well, it was my last shot.” Looking back, having read other people’s summations, interviews and the couple of books that have been written about me, everybody believes I was 20, 30, 40, or 50 years ahead of my time.

With “My Country ’Tis of Thy People You’re Dying” from 1966, I was trying to give people Indian 101 in six minutes, because so many people wondered where they can find out the facts. By talking about genocide, I wasn’t trying to be 50 years ahead of my time, but it took Canada 50 years to get around to truth and reconciliation. It’s easier to write a song about something than it is to pull off what it is that’s going to correct what needs to be fixed.

I turned down people who wanted to write biographies about me from the ‘60s to the ‘80s. But it was nice to work with both Andrea Warner and Blair Stonechild on the books they wrote on me. Blair is the head of Native Studies at the University of Regina. He’s from the reserve next to mine. I knew that a typical rock and roll biographer would not know what to ask, let alone who else to ask when it comes to anything. I’m Indigenous. Blair speaks Cree. He knows my family and I was very comfortable with him. He was able to build a piece of what I’m calling my legacy—my story. He was able to reach deep into that part of who I am for his It's My Way from 2012. But he’s not a music journalist. He had nothing to do with music.

When Andrea came along, Blair’s book was already there to inform her about the stuff she couldn’t have got to herself for The Authorized Biography from 2018. Andrea isn’t just a scholar and a great writer, but a feminist, and lots of fun. We really hit it off. I trusted her and she knew how to listen, what to ask and how to comment. In a way, if I had died 10 years ago, I would have felt I had missed the boat, but now, with the books Blair and Andrea have done, I feel like they’ve managed to sew together the various points of my story that have been important to me.

I feel my best albums, including Buffy, Changing Woman and Moonshot weren’t heard and didn’t get their due. I didn’t have a shark or a manager who could push the music up somebody’s nose, into their pants or wherever it is they all go these days. You and I know how it’s done. It’s not just about the music. It’s about having a businessperson who can deal with the realities of showbiz. That’s no small task.

Did you notice the beaded necklace I wore when you saw me play at my last San Francisco show? That’s how I think of my legacy. My legacy is how people see the things I’ve done and how it all goes together. Each bead is an individual something for me. It’s a song, a lyric, the meaning of the song, who I wrote something for, or what was going on in the world when I wrote a song. And the idea of one of those big-beaded necklaces isn’t something I got from Vogue magazine. Nobody else is wearing it. I treasure uniqueness in other people and I tolerate it and appreciate it in myself.

I also think another part of my legacy is what you said to me during the lovely, beautiful rap you gave me when you told me how much you liked that last San Francisco show. My excitement is real when people appreciate what I do.

The problem with the human race is we’re young. Each of us unique and we all see great things. We also make mistakes. We wet our pants. We spill our milk. We blame our brothers and sisters. But I feel as though each of us is evolving with every minute that goes by. For me, there’s a connection between my own legacy and how I see the world. I’ve done some wonderful things and I’ve seen some wonderful things in the world that other people have done. So, I see the human race in both its glory and youth.

But I also really feel there are some people you can’t explain. We’re in political kindergarten at the moment. It’s as if they’re going to be seven-year-old brats forever. We’re in a weird place, but it’s not the first time we’ve experienced bad leadership. But, because of that, for a lot of people, it’s their first time having to step up and be a citizen in response to that. We better take it seriously. It’s important. Believe it. None of us can throw in the towel. I think that’s part of my legacy, too. It’s part of what shows through in every single song. I can’t think of any of my songs that are super-negative. If I write a song that's hard hitting like “My Country 'Tis of Thy People You're Dying,” it's with a reason. I'm always trying to move this thing forward and to see each day as new, not only for me, but for everybody else.

Photo: Matt Barnes

Photo: Matt Barnes

How does spirituality inform your music?

It's the Mother and the motherlode all at the same time for me.

I always say that as an artist, I'm kind of an overgrown kindergarten kid—painting, dancing, playing music, and making songs after school. Schools flunked me in music because I play by ear instead of by eye. That is, I'm dyslexic in music and have never learned how to sight read. I can write music, but cannot read it. So, I do pretty much the same kinds of things in the same way as I did as a little kid, and it's all completely natural for me.

However, with natural musicians, there's no money for the teachers, and you can get punished instead of rewarded for being good without benefit of their services. That is, you can pay a music teacher to show you how to read notes, but a natural gift cannot be bought and sold, and unfortunately is often resented. It's like, without that money element, there is no business, and "we're in business.” Kids like me are typically shunned and shamed in music class. Not allowed in band. Don't qualify for an instrument. But if you pay someone to teach you how to read the code, you are allowed in. For me, that's a metaphor for what's wrong with business, especially the music business.

"Made in the image of the creator"—that's our green light for creativity. We are supposed to be creative. It's natural and no big deal, but also a very big deal—the biggest deal of all. We are supposed to develop, grow, change, and evolve in everything, including works of art, families, neighborhoods, and scientific discoveries.

The natural gift of creativity, which has been my companion, my playmate, my savior from boredom, my rescuer from bullies, and my true adventure, is all wrapped up in the creator, creativity and the creation. To me they're all part of the same thing. Simple and sacred.

Special thanks to Mark Olexson.