D.B. Cooper – Disappearing in the Wilderness – Legends of America (original) (raw)

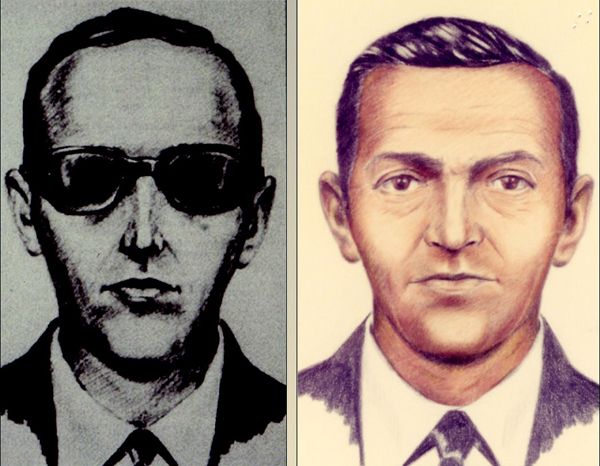

D.B. Cooper Sketch

On the afternoon of November 24, 1971, a nondescript man calling himself Dan Cooper approached the counter of Northwest Orient Airlines in Portland, Oregon, and used cash to buy a one-way ticket on Flight #305, bound for Seattle, Washington. Thus began one of the great unsolved mysteries in FBI history.

Cooper was a quiet man who appeared to be in his mid-40s, wearing a dark business suit, black tie, white shirt, and sunglasses. He was described as about 6 feet tall and weighing about 170 pounds.

He ordered a drink—bourbon and soda—while the flight was waiting to take off. Shortly after 3:00 p.m., he handed the stewardess a note demanding 200,000(equivalentto200,000 (equivalent to 200,000(equivalentto1,170,000 in 2015) in ransom and indicated she sit with him. The stunned stewardess did as she was told, and Cooper opened a cheap briefcase and showed the contents, which were red cylinders connected with wires that he said was a bomb. He then instructed her to write down what he told her and sent her to the cockpit with a note for the pilots, which demanded the ransom of $200,000 in twenty-dollar bills and four parachutes.

The pilot, William Scott, contacted Seattle-Tacoma Airport air traffic control, which in turn informed local and federal authorities. Upon nearing the airport, the 36 other passengers were informed that their arrival in Seattle would be delayed because of a “minor mechanical difficulty,” and the plane began to circle Puget Sound. In the meantime, Northwest Orient’s president, Donald Nyrop, authorized the ransom payment and ordered all employees to cooperate fully with the hijacker. In Seattle, the money was obtained from several local banks to be delivered to the plane and the parachutes. Once the FBI had assembled the parachutes and ransom money, and emergency personnel had been mobilized, the pilot was given the ok to land.

With his demands met, Cooper allowed the 36 other passengers and two stewardesses to depart the plane. He then instructed the pilot to fly to Mexico City at no more than 10,000 feet at a low speed. After locking up the other crew members, he remained alone in the subzero temperatures of the cabin with the rear door open and steps down. En route, the pilot stopped in Reno, Nevada, for refueling. At that point, he assumed Cooper was still on board; however, the hijacker, the money, two parachutes, and the briefcase with its red cylinders were missing.

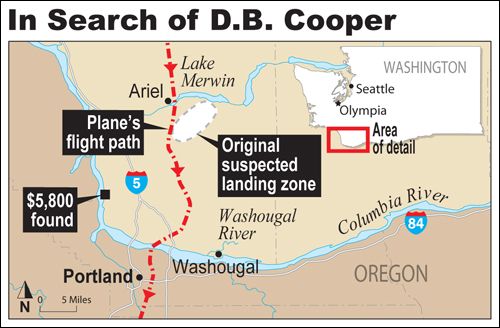

Somewhere between Seattle and Reno, a little after 8:00 p.m., the hijacker had jumped out of the back of the plane with the ransom money.

The investigation immediately accelerated, and a search began for Cooper. The investigation called NORJAK, for Northwest Hijacking, would last for decades as the FBI interviewed hundreds of people, tracked leads across the nation, and scoured the aircraft for evidence. By the fifth anniversary of the hijacking, the FBI had considered more than 800 suspects and eliminated all but two dozen from consideration.

In the beginning, investigators thought that Cooper was an experienced jumper; however, they concluded that he wasn’t, as an experienced parachutist would never jump on a dark night, in the rain, with 200-mile-an-hour winds, wearing loafers and a trench coat, into a densely forested area. The odds of survival were too low. Cooper also didn’t notice that the reserve chutes of the parachutes he’d been given were sewn shut — something an experienced skydiver would have checked. They also investigated whether Cooper may have had an accomplice on the ground, but that was ruled out, as it would have required coordinating closely with the flight crew so he could jump at just the right moment and hit a designated drop zone. There was no coordination, as Cooper simply said, “Fly to Mexico.”

Money found from D.B. Cooper Hijacking.

During the years-long investigation, several suspects were considered, including Richard Floyd McCoy, who had been arrested for a similar airplane hijacking and escape by parachute less than five months after Cooper’s flight. However, he was ruled out because he didn’t match the physical description and had a strong alibi. Another was a man named Duane Weber, who claimed to be Cooper on his deathbed. However, he was ruled out with a DNA sample.

In 1978 a placard containing instructions for lowering the aft stairs of a Boeing 727 was found by a deer hunter near a logging road about 13 miles east of Castle Rock, Washington, within the basic path of Flight 305. Two years later, in February 1980, an eight-year-old who was vacationing with his family on the Columbia River about 9 miles downstream from Vancouver, Washington, found a deteriorating package full of twenty-dollar bills ($5,800 in all) that matched the ransom money serial numbers.

No other evidence has ever been found. Most investigators believe that it is unlikely that Cooper survived the jump as the weather conditions were unforgiving, his clothing and shoes were unsuitable for landing, he had no survival equipment for the wilderness, and seemingly, he had no accomplice on the ground. This scenario would have been extremely dangerous for a seasoned pro, which evidence suggests Cooper was not.

In July 2016 — 44 years, seven months, and 18 days after the hijacking—the FBI announced it is closing the Cooper case to focus on higher-priority cases. However, they opened the volumes of evidence gathered thus far to the public. In 2017 an alleged parachute strap, decades old, was found by a group of volunteer investigators. That same year a piece of foam alleged to be part of Cooper’s backpack also emerged.

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated November 2022.

D.B. Cooper Search Map

Also See:

The FBI and the American Gangster

Gangsters, Mobsters & Outlaws of the 20th Century

Sources: