History of the FBI – Legends of America (original) (raw)

Federal Bureau of Investigation.

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the United States’ domestic intelligence and security service and its principal federal law enforcement agency. It operates under the jurisdiction of the United States Department of Justice and reports to both the Attorney General and the Director of National Intelligence.

Theodore Roosevelt, 1905.

The FBI originated from a force of Special Agents created in 1908 by Attorney General Charles Bonaparte during Theodore Roosevelt’s presidency. When the two first met in 1892, Roosevelt, then Civil Service Commissioner, boasted of his reforms in federal law enforcement. This was a time when law enforcement was often political rather than professional. Roosevelt spoke with pride of his insistence that Border Patrol applicants pass marksmanship tests, with the most accurate getting the jobs.

The two men believed that efficiency and expertise, not political connections, should determine who could best serve in government. When Roosevelt became President of the United States in 1901, he appointed Bonaparte Attorney General. In 1908, Bonaparte applied their Progressive philosophy to the Department of Justice by creating a corps of Special Agents. It had neither a name nor an officially designated leader other than the Attorney General. Yet, these former detectives and Secret Service men were the forerunners of the FBI.

National Climate Leading Up to Its Creation

Today, most Americans take for granted that our country needs a federal investigative service, but in 1908, establishing this kind of agency at a national level was highly controversial. The U.S. Constitution is based on “federalism:” a national government with jurisdiction over matters that cross boundaries, like interstate commerce and foreign affairs, with all other powers reserved to the states. Throughout the 1800s, Americans usually looked to cities, counties, and states to fulfill most government responsibilities. However, by the 20th century, more accessible transportation and communications had created a climate of opinion favorable to the federal government, establishing a solid investigative tradition.

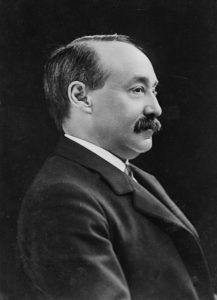

Attorney General Charles Bonaparte.

The American people’s impulse toward a responsive federal government, coupled with an idealistic, reformist spirit, characterized what is known as the Progressive Era from approximately 1900 to 1918. The Progressive generation believed government intervention was necessary to produce justice in an industrial society. Moreover, it looked to “experts” in all phases of industry and government to produce that just society.

President Roosevelt personified Progressivism at the national level. A federal investigative force of well-disciplined experts designed to fight corruption and crime fit Roosevelt’s Progressive government scheme. Attorney General Bonaparte shared his President’s Progressive philosophy. However, the Department of Justice under Bonaparte had no investigators except for a few Special Agents who carried out specific assignments for the Attorney General and a force of Examiners (trained as accountants) who reviewed the financial transactions of the federal courts. Since its beginning in 1870, the Department of Justice used funds appropriated to investigate federal crimes to hire private detectives first and later investigators from other federal agencies. (Federal crimes are considered interstate or occurred on federal government reservations.)

Secret Service Men, about 1915.

By 1907, the Department of Justice most frequently called upon Secret Service “operatives” to conduct investigations. These men were well-trained, dedicated — and expensive. Moreover, they reported not to the Attorney General but to the Chief of the Secret Service. This situation frustrated Bonaparte, who wanted complete control of investigations under his jurisdiction. Congress provided the impetus for Bonaparte to acquire his own force. On May 27, 1908, it enacted a law preventing the Department of Justice from engaging Secret Service operatives.

The following month, Attorney General Bonaparte appointed a force of Special Agents within the Department of Justice. Accordingly, ten former Secret Service employees and several Department of Justice investigators became Special Agents of the Department of Justice. On July 26, 1908, Bonaparte ordered them to report to Chief Examiner Stanley W. Finch. This action is celebrated as the beginning of the FBI.

Both Attorney General Bonaparte and President Theodore Roosevelt, who completed their terms in March 1909, recommended that the force of 34 Agents become a permanent part of the Department of Justice. Attorney-General George Wickersham, Bonaparte’s successor, named the force the Bureau of Investigation on March 16, 1909. At that time, the title of Chief Examiner was changed to Chief of the Bureau of Investigation.

Early Days

Bureau of Investigation by Harris & Ewing, 1923.

When the Bureau of Investigation was established, there were few federal crimes. The Bureau primarily investigated violations of laws involving national banking, bankruptcy, naturalization, antitrust, peonage, and land fraud. Because the early Bureau provided no formal training, previous law enforcement experience or a background in the law was considered desirable.

The first significant expansion in Bureau jurisdiction came in June 1910, when the Mann (“White Slave”) Act was passed. This act made it a crime to transport women over state lines for immoral purposes and provided a tool for the federal government to investigate criminals who evaded state laws but had no other federal violations. Finch became Commissioner of White Slavery Act violations in 1912, and former Special Examiner A. Bruce Bielaski became the new Bureau of Investigation Chief.

Over the next few years, the number of Special Agents grew to more than 300, and another 300 support employees complemented these individuals. Field offices existed since the Bureau’s inception. Each field operation was controlled by a Special Agent in Charge responsible to Washington. Most field offices were located in major cities. However, several were located near the Mexican border, where they concentrated on smuggling, neutrality violations, and intelligence collection, often in connection with the Mexican Revolution.

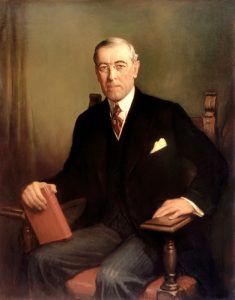

President Woodrow Wilson, 1913.

With the United States’ entry into World War I in April 1917 during Woodrow Wilson’s administration, the Bureau’s work increased again. As a result of the war, the Bureau acquired responsibility for the Espionage, Selective Service, and Sabotage Acts and assisted the Department of Labor by investigating enemy aliens. During these years, Special Agents with general investigative experience and facility in specific languages augmented the Bureau.

William J. Flynn, former head of the Secret Service, became Director of the Bureau of Investigation in July 1919 and was the first to use that title. In October 1919, the passage of the National Motor Vehicle Theft Act gave the Bureau of Investigation another tool by which to prosecute criminals who had previously evaded the law by crossing state lines. With the country’s return to “normalcy” under President Warren G. Harding in 1921, the Bureau of Investigation returned to its pre-war role of fighting a few federal crimes.

Al Capone.

The years from 1921 to 1933 were sometimes called the “lawless years” because of the many gangsters and the public disregard for Prohibition, which made it illegal to sell or import intoxicating beverages. Prohibition created a new federal medium for fighting crime, but the Department of the Treasury, not the Department of Justice, had jurisdiction over these violations.

Attacking crimes that were federal in scope but local in jurisdiction called for creative solutions. The Bureau of Investigation had limited success using its narrow jurisdiction to investigate some of the criminals of “the gangster era.” For example, it investigated Al Capone as a “fugitive federal witness.”

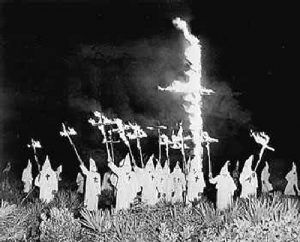

A federal investigation of a resurgent white supremacy movement also required creativity. The Ku Klux Klan, dormant since the late 1800s, was revived partly to counteract the economic gains made by African Americans during World War I. The Bureau of Investigation used the Mann Act to bring Louisiana’s philandering Ku Klux Klan “Imperial Kleagle” to justice.

Ku Klux Klan.

Through these investigations and other more traditional investigations of neutrality violations and antitrust violations, the Bureau of Investigation gained stature. Although the Harding Administration suffered from unqualified and sometimes corrupt officials, the Progressive Era reform tradition continued among the professional Department of Justice Special Agents. The new Bureau of Investigation Director, William J. Burns, who had previously run his own detective agency, appointed 26-year-old J. Edgar Hoover as Assistant Director. Hoover, a George Washington University Law School graduate, had worked for the Department of Justice since 1917. He headed the enemy alien operations during World War I and assisted in the General Intelligence Division under Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer, investigating suspected anarchists and communists.

After President Harding died in 1923, his successor, Calvin Coolidge, appointed replacements for Harding’s cronies in the Cabinet. Coolidge appointed attorney Harlan Fiske Stone as the new Attorney General, who, on May 10, 1924, selected Hoover to head the Bureau of Investigation. By inclination and training, Hoover embodied the Progressive tradition. His appointment ensured that the Bureau of Investigation would keep that tradition alive.

J. Edgar Hoover, 1924.

When J. Edgar Hoover took over, the Bureau of Investigation had approximately 650 employees, including 441 Special Agents working in nine city field offices. By the decade’s end, there were approximately 30 field offices, with Divisional headquarters in New York, Baltimore, Atlanta, Cincinnati, Chicago, Kansas City, San Antonio, San Francisco, and Portland.

He immediately fired those unqualified agents and proceeded to professionalize the organization. For example, Hoover abolished the seniority rule of promotion and introduced uniform performance appraisals. He also scheduled regular inspections of the operations in all field offices. Then, in January 1928, Hoover established a formal training course for new Agents, including the requirement that New Agents had to be in the 25-35 year range to apply. He also returned to the earlier preference for Special Agents with law or accounting experience.

The new Director was also keenly aware that the Bureau of Investigation could not fight crime without public support. In remarks prepared for the Attorney General in 1925, he wrote, “The Agents of the Bureau of Investigation have been impressed with the fact that the real problem of law enforcement is in trying to obtain the cooperation and sympathy of the public and that they cannot hope to get such cooperation until they themselves merit the respect of the public.” Also, in 1925, Agent Edwin C. Shanahan became the first Agent to be killed in the line of duty when he was murdered by a car thief named Martin J. Durkin.

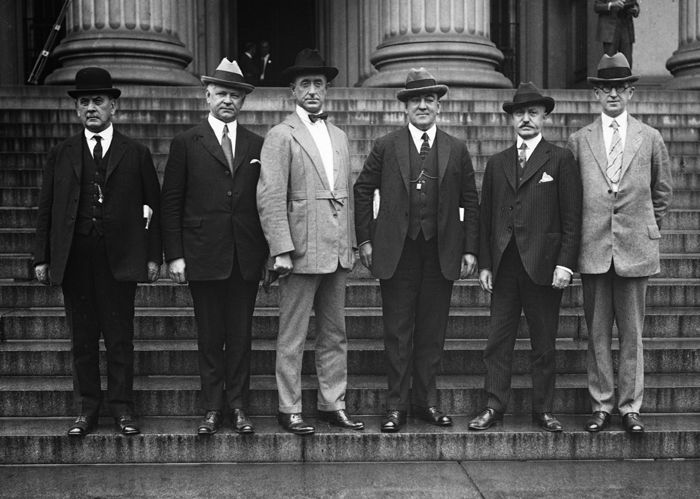

J. Edgar Hoover, at left, with staff by Harris & Ewing, 1926.

In the early days of Hoover’s directorship, a long-held goal of American law enforcement was achieved: the establishment of an Identification Division. Tracking criminals utilizing identification records had been considered a crucial tool of law enforcement since the 19th century, and matching fingerprints was considered the most accurate method. By 1922, many large cities had started their own fingerprint collections.

In keeping with the Progressive Era tradition of federal assistance to localities, the Department of Justice created a Bureau of Criminal Identification in 1905 to provide a centralized reference collection of fingerprint cards. In 1907, the collection was moved, as a money-saving measure, to Leavenworth Federal Penitentiary, which convicts staffed. Understandably suspicious of this arrangement, police departments formed their own centralized identification bureau maintained by the International Association of Chiefs of Police. It refused to share its data with the Bureau of Criminal Investigation. In 1924, Congress was persuaded to merge the two collections in Washington, D.C., under the Bureau of Investigation administration. As a result, law enforcement agencies across the country began contributing fingerprint cards to the Bureau of Investigation by 1926.

By the end of the decade, Special Agent training was institutionalized, the field office inspection system was solidly in place, and the National Division of Identification and Information collected and compiled uniform crime statistics for the entire United States. In addition, studies were underway that would lead to the creation of the Technical Laboratory and Uniform Crime Reports. The Bureau was equipped to end the “lawless years.” It was in 1935 that the organization added the word Federal to its name and became the “FBI.”