Women in the Army – Legends of America (original) (raw)

By William Worthington Fowler in 1877

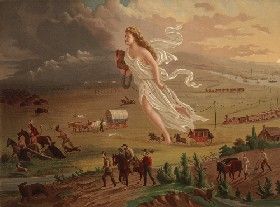

American Progress by John Gast in 1872.

In the great wars of American history, there are, in immediate connection with the army, two situations in which woman more prominently appears: the former is where, in her proper person, she accompanies the army as a “vivandiere,” or as the daughter of the regiment, or as the comrade and helpmate of her husband; the latter, and less frequent capacity, is that of a soldier, matching in the ranks and facing the foe in the hour of danger. During the American Revolution, many brave and devoted women served in the army, principally in their true characters as wives of regularly enlisted soldiers. They kept even steps with the ranks upon the march and cheerfully shared the burdens, privations, hardships, and dangers of military life.

In some cases where both wife and husband fought for independence, the wife even surpassed her husband in those heroic virtues. The name of Mrs. Jemima Warner has been embalmed in history as one of those remarkable women who was seen at once as the faithful wife, the heroine, and the patriot.

She appears to have been a native of Lancaster, Pennsylvania, and became the wife of James Warner, a private in Captain Smith’s company, Daniel Morgan’s rifle corps. In 1775, she followed her husband North and joined him at Prospect Hill, Cambridge, in the fall of that year. Morgan’s riflemen were picked men and were sure to be placed in the posts where the most significant danger threatened.

But James Warner, though a stalwart man in appearance, possessed none of the qualities demanded in extraordinary emergencies. If ever a man needed a constant companion, superior to himself, in hardship and danger, it was Private James Warner, and such a companion was his wife, Jemima. She is described as gifted with the form and personal characteristics of a true heroine. Her heroic qualities through all the romantic and tragic campaigns against Canada prove that her spirit corresponded to the frame it animated.

The March to Quebec by Kenneth Roberts.

The Canadian campaign was the severest and most trying of any during the Revolution. General Arnold’s march through the woods of Maine was attended with delays, misfortunes, and losses that would have discouraged any but the bravest, most determined, and hardy. Wearisome marches, floods, winter’s cold, and famine tested the men’s strength and fortitude to the utmost, and in these crises, Private Warner was one of those few whose soldiership failed to stand the test.

The advanced guard of the army of the wilderness was composed of Morgan’s troops, who, with incredible labor and hardship, ascended the Dead River and crossed the highlands into the Canadian frontier, 120 miles from Quebec, with their last rations in their knapsacks, and with their passage obstructed by a vast swamp overflowed with water from two to three feet deep. Smith’s and Hendrick’s companies reached it first and halted to wait for stragglers. Mrs. Warner came up with another woman, the wife of Sergeant Grier, of Hendrick’s company–as much a heroine as herself, though less unfortunate in her experience. The soldiers were entering the water, breaking the ice with their gunstocks, and the women courageously wading after them when someone shouted, “Where is Warner?”

Jemima, who had not noticed her husband’s disappearance, started searching for him. Warner was no worse than many other men, but his grit had given out. Begging his comrades to delay their march for a while, she hurried back in search of her husband, but an hour passed, and his company marched without him.

Without the necessary forethought for endurance, he had eaten all his rations, which should have lasted him two days. Knowing that the army’s supplies were exhausted, he saw no hope ahead. His brave wife had had a sad trial with him. From the day provisions began to be scarce, he had been the same improvident laggard.

Familiar with his failings, she was in the habit of hoarding food, the price of her secret fastings, against such a need. She now exerted herself to the utmost to rouse him and induce him to press on and rejoin his comrades. It was long before she prevailed, and at last, when they started, the army had gone on, and the pair were forced to make their way through the wilderness alone.

Refusing to entertain the thought of perishing in the wilderness, she did her best to cheer her husband and drive such thoughts from his mind. Endowed with a strong constitution and disease-free, the young soldier could have survived the terrible march to Canada had he possessed a little of her courage and good sense. Taking the lead in the bitter journey, through swamps and snows, threading the tangled forests, climbing cliffs, and fording half-frozen creeks, — day after day, the heroic woman pushed her faint-hearted husband on, feeding him from her little store of ember-baked cakes, and eating almost nothing herself until they were more than halfway to Sertigan on the Chaudiere River, toward Quebec.

Here, Warner dropped down, wholly discouraged, and resisted all his wife’s pleas to rise again. In vain, she appealed to every motive that could nerve a soldier, every sentiment that could inspire and stimulate a man. She said relief must be before them and not far away; for her sake, would he not try again?

Her pleadings and her tears were wasted. The faint-hearted soldier had made his last halt. Weak he undoubtedly was, but comparing the nourishment each had taken, she should have been physically worse off than he. The superiority of her mental and moral organization kept her from sinking as low as her husband. Failing to stir him to make another effort to save himself, she filled his canteen with water, and, placing that and the little remnant of her wretched bread between his knees, she turned away and went down the river with a heavy but dauntless heart, searching for help.

Soldiers in the snow in the American Revolution, Peter George, 1920

On her way, she met a boat coming up the river, and in it were two army officers and two friendly Indians. Hailing the party, she told them of her distress and begged them to take her husband on board. They replied that it was impossible. They had been sent after Lieutenant Macleland, a sick officer left behind with an attendant, at Twenty-foot Falls, and the little birch bark canoe would only carry two more men. They could only spare her enough food to keep her alive. Weeping, she turned back and sadly followed the canoe up the stream until it was lost to view. When she again reached the spot where she had left her discouraged husband, she found him alive but helpless and sinking fast. While the devoted wife sat by his side, doing what little she could for his comfort, the canoe party came down the river, bearing the gallant Macleland, their loved but dying officer. Again, the hapless wife begged, with pitiful tears, that they would take her husband in. No! All her prayers were useless. Macleland was worth more than Warner.

When all hope had fled, Jemima stayed faithfully by her husband till he had breathed his last. She could only close his eyes and try to cover his body from the wolves. Then, when love had done its best, she strapped his powder horn and pouch to her person, shouldered his rifle, and set out on her weary tramp toward Quebec. Melancholy as it was, one sees a certain sublimity in the woman’s act of selecting and carrying with her those warlike keepsakes. It was in perfect keeping with those tragic times. The tender thoughtfulness of her poor husband’s martial honor outlived her power to inspire him again to her heroism and made her grand in the forlornness of her sorrow. She was determined that his arms should go to the war if he could not.

Nursing a soldier.

The same brave mind that had made her so admirable as a soldier’s helpmate upheld her through tedious hardships and continued perils on her lonely way to the settlement. Once there, she needed to wait until she could recover her exhausted strength. Her triumph over the severe tasking of all those bitter days in the wilderness, without chronic injury or even temporary sickness, would now be called a miracle of endurance in a woman.

As she passed from parish to parish, the simple Canadian peasant, always friendly to the American cause, welcomed the handsome young woman with warm hospitality. The story of her singular bravery and devotion had reached their ears.

Her subsequent life and history are shrouded in obscurity. We know not whether she married a husband worthier of such a partner in those trying times or whether she retired to brood alone over a sorrow with which shame for the object of her grief must have mingled. Whatever her lot may have been, her name deserves a place on the golden roll of our revolutionary heroines. [Later history tells us that Jemima Warner was killed, the first female casualty of war in the United States.]

As we have already remarked, only a few instances are on record where women served as enlisted soldiers in the Army of the Revolution. Occasional services performed under the guise of men were more frequent. As bearers of dispatches disguised as couriers, they glided through the enemy’s lines. Donning their father’s or brother’s overcoats and hats, they deceived the besiegers of the garrison into the belief that soldiers were not lacking to defend it and even ventured in male habiliments to perform more perilous feats: such, for example, the following:

Soldier.

Grace and Rachel Martin, the wives of two brothers who were absent with the patriot army, receiving intelligence one evening that a courier under the guard of two British officers would pass their house on a particular night with important dispatches, resolved to surprise the party and obtain the papers.

Disguising themselves in their husband’s outer garments and providing themselves with arms, they waylaid the enemy. The courier and his escort appeared soon after they took their station by the roadside.

At the proper moment, the disguised ladies sprang from their bushy covert and, presenting their pistols, ordered the party to surrender their papers. Surprised and alarmed, they obeyed without hesitation or the least resistance. Having put them on parole, the brave women hastened home by the nearest route, a bypath through the woods, and dispatched the documents to General Greene.

Perhaps the most remarkable case of female enlistment and protracted service in the patriot army was that of Deborah Samson. This woman’s career shows that her motive in adopting and following a soldier’s career was praiseworthy. The whole country was aglow with patriotic fervor, and in no section did the flame burn with a purer luster than in that where Deborah was nurtured. In those straitlaced days, it was not idle curiosity nor mere love of roving that incited her to abandon her home and join in the perilous fray where the standard of freedom was “fully high advanced.” She had counted the cost of the extraordinary step that she was about to take but found in the difficulties and dangers that entailed nothing to obstruct or daunt her purpose.

Deborah Sampson Gannett.

Her parents were in humble circumstances and lived in Plymouth, Massachusetts, where Deborah grew up with slender advantages for anything more than a practical education. Yet such was her diligence in the acquisition of knowledge that before she was eighteen, she had shown herself competent to take charge of a district school, in which duty she displayed some of the same qualities that made her after-career remarkable.

For several months, she seems to have cherished the secret purpose of enlisting in the American army, and with that view, she laid aside a small sum from her scanty earnings as a schoolteacher, with which she purchased a quantity of coarse fustian out of this material, working at intervals and by stealth, she made a complete suit of men’s clothes, concealing each article as it was finished in a haystack.

When her preparations had been completed, she informed her friends that she was searching for higher wages for her labor. Tying her new suit of men’s attire in a bundle, she took her departure. She probably availed herself of the nearest shelter to assume her disguise. Her stature was lofty for a woman, and her features, though finely proportioned, were of a masculine cast. When, at a subsequent period, she had donned the buff and blue regimentals and marched in the ranks of the patriot army, she was said to have looked every inch the soldier.

Pursuing her way, she presented herself at the American army camp as one of those patriotic young men who desired to assist in opposing the British and securing their country’s independence.

Her friends, supposing that she was engaged at service at some distant point, made little inquiry as to her whereabouts, knowing her self-reliance and ability to follow out her career without their counsel or assistance. Those nearest her appear to have never made such a search for her as would have led to her discovery.

Having decided to enlist for the whole term of the war, from motives of patriotism, she was received and enrolled as one of the first volunteers in the company of Captain Nathan Thayer of Medway, Massachusetts, under the name of Robert Shirtliffe. As the young recruit appeared to be without friends and homeless, she interested Captain Thayer and was received into his family while recruiting his company. Here, she remained for some weeks and received her first lessons in the drill and duties of the young soldier.

Accustomed to labor from childhood upon the farm and in outdoor employment, she had acquired unusual vigor of the constitution; her frame was robust and of masculine strength; and, having thus gained a degree of hardihood, she was enabled to acquire great knowledge and precision in the manual exercise, and to undergo what a female, delicately nurtured, would have found it impossible to endure. Soon after they had joined the company, the recruits were supplied with uniforms by a kind of lottery. That drawn by Robert did not fit, but, taking needle and scissors, he soon altered it to suit him. To Mrs. Thayer’s expression of surprise at finding a young man so expert in using the implements of feminine industry, the answer was that his mother having no girl, he had been often obliged to practice the seamstress’s art.

While in Captain Thayer’s family, she was thrown into the society of a young girl who then visited Mrs. Thayer. She soon began to show much partiality for Deborah (or Robert), and as she seemed to be versed in the arts of coquetry, Robert felt no scruples in paying close attention to one so volatile and fond of flirtation; she also felt a natural curiosity to learn within how short a time a maiden’s fancy might be won.

Mrs. Thayer regarded this little romance with some uneasiness, as she could not help perceiving that Robert did not entirely reciprocate her young friend’s affection. She accordingly lost no time in remonstrating with Robert and warning him of the severe consequences of his folly in trifling with the maiden’s feelings. The remonstrance and caution were good-naturedly received, and the departure of the blooming soldier soon after terminated all these love passages. However, Robert received souvenirs from his fair young friend, which he cherished as relics in after years.

For three years, until 1781, our heroine appeared as a soldier. During this time, she gained the approbation and confidence of the officers by her exemplary conduct and the fidelity with which her duties were performed. When under fire, she showed an unflinching boldness and volunteered in several hazardous enterprises. The first time she was wounded was in a hand-to-hand fight with a British dragoon when she received a severe sword cut in the side of her head, laying bare her skull.

Deborah Sampson Gannett.

About four months after the first wound, she was again doomed to bleed in her country’s cause, receiving another severe wound in her shoulder, the bullet burying itself deeply and necessitating a surgical examination.

She described her first emotion when the ball struck her as a sickening terror lest her sex should be discovered. The pain of the wound was scarcely felt in her excitement and alarm. Even death on the battlefield, she felt, would be preferable to the shame that would overwhelm her in case the mystery of her life were unveiled. Her secret, however, remained undiscovered, and, recovering from her wound, she was soon able again to take her place in the ranks.

Sometime after, she was seized with a brain fever, which was then prevalent in the army. During the first stages of her sickness, her greatest suffering was the dread that consciousness would desert her, and her carefully guarded secret would be disclosed to those about her. She was carried to the hospital, where her case was considered a hopeless one. One day, the doctor approached the bed where she lay, a corpse, as everyone supposed. Taking her hand, he found the pulse feebly beating, and, attempting to place his hand on the heart, he discovered a female patient whom he had little expected. The surgeon said not a word of his discovery. Still, with prudence, delicacy, and generosity ever afterward appreciated by the sufferer, he provided every comfort her perilous condition required. He paid her that medical attention that soon secured her return to consciousness. As soon as her condition would permit, he had her removed to his own house, where she could receive better care.

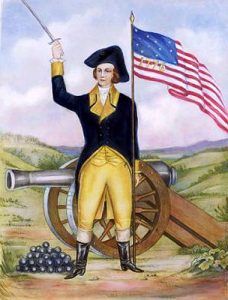

General Washington.

After her health was nearly restored, Doctor Binney, her generous benefactor, had a long conference with the company’s commanding officer in which Robert had served, followed by an order to the youth to carry a letter to General Washington.

Ever since her removal into the doctor’s family, she had entertained the suspicion that he had discovered the secret of her life. Often, while conversing with him, she watched his face with anxiety but never discovered a word or look to indicate that the physician knew or suspected that she was other than what she represented herself to be. But when she received the order to carry the letter to the commander-in-chief, her long-cherished misgivings became, at last, a certainty.

The order must be obeyed. With a trembling heart, she pursued her course at the headquarters in Washington. When she was ushered into the presence of the Chief, she was overpowered with dread and uncertainty, and the alarm and confusion she felt showed upon her face. Washington kindly endeavored to reassure her, noticing her agitation and supposing it to arise from diffidence. She was soon bidden to retire with an attendant while he read the communication she had been the bearer.

In a few moments, she was again summoned to Washington’s presence, who handed her a discharge from the service in silence, with a note containing a few brief words of advice and a sum of money sufficient to bear her expenses to someplace where she might find a home. To her latest hour, she never forgot the delicacy and forbearance shown her by that great and good man.

After the war was over, she became the wife of Benjamin Gannet. During General Washington’s presidency, she was invited to visit the seat of government, and during her stay at the capital, Congress granted her a pension and certain lands in consideration of her services to the country as a soldier.

In the War of 1812, women shared more or less the hard and perilous duties of soldiers, especially upon the Canadian border and on the western frontier, where Indian hostilities now broke out afresh. She stood guard in the homes exposed to attack all along the thin line, which the savage or the British soldier threatened to break through, and on more than one battlefield, she proved her lineal descent from the brave mothers of the Revolution.

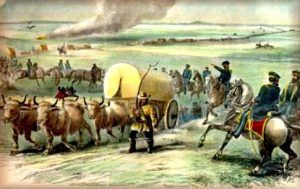

Army Train on the Santa Fe Trail.

To the female imagination, the Mexican-American War must have been clothed with peculiar hardships and dangers. The length of the marches, the vast distance from home, the torrid heat, the diseases that prevailed in that clime, and the nature of the half-civilized enemy all conspired to warn the gentler sex against taking part in that conflict. And yet, all these appalling difficulties and perils could not damp the martial ardor of Mrs. Coolidge. She was born in Missouri, where, in St. Louis, she married her husband, a Mexican trader. Accompanying him on one of his yearly journeys to Santa Fe, she had the misfortune to see him meet his death at the hands of a Mexican bravo on the outskirts of that city.

Her life had been a stirring one from her early girlhood. When war broke out with Mexico, she attired herself in manly garments and readily passed muster with the recruiting officer by her stature and a rather masculine appearance. Under the name of James Brown, she was duly entered on the rolls of a Missouri company, which soon after took a steamboat for Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, the rendezvous point. From this point, on the 16th of June, 1846, a force of 1,658 men, including our heroine, took up their line of march to Santa Fe, New Mexico.

Most of this little army was mounted men, and of this number was Mrs. Coolidge, an admirable horsewoman. Their course lay over the almost boundless plains stretching westward to the Rocky Mountain foothills, a distance of nearly 1,000 miles.

General Stephen W. Kearny.

In 50 days, they reached Santa Fe, which they took possession of without opposition. Mrs. Coolidge’s soldierly bearing and quick intelligence soon attracted the attention of General Stephen Kearny, the commanding officer, who selected her to be one of the bearers of dispatches to the war department.

A picked mustang, of extraordinary grit and endurance, was placed at her disposal; a strong and fleet horse of the messenger stock, crossed with the mustang, was selected for her guide, a sturdy Scotchman, formerly in the Santa Fe trade; and one bright day, early in September, they set out on their long and difficult journey for Leavenworth. The first 16 miles, over a broken and hilly country, were void of the incident. They had passed through Arroyo Hondo and reached the El Boca del Cañon, one of the gateways to Santa Fe; as they were threading this narrow pass, they saw, on turning a short angle of the precipice that towered three hundred feet above them, four mounted Mexicans, armed to the teeth and prepared to dispute their passage. One of them dismounted and, advancing towards our couriers, waved a white handkerchief and demanded their surrender in Spanish and in broken English. The guide replied in very concise English, telling him to go to a place unmentionable to polite ears.

The envoy immediately rejoined his companions and mounted his horse; the party then turned and trotted forward a few paces as if they were about to give Mrs. Coolidge and the guide a free passage when they suddenly wheeled their horses, and, discharging their pieces, seized their lances and dashed down full tilt upon our heroine and her guide. A shot from the guide’s rifle hurled one of the Mexicans out of his saddle like a stone from a sling. Mrs. Coolidge was less fortunate in her aim; missing the rider, her bullet struck a horse full in the forehead, but such was the speed with which it was approaching that it was carried within twenty paces of the spot where she stood before it fell; the rider, uninjured, quickly extricated himself, and, seizing from his holster a horse-pistol, shot Mrs. Coolidge’s horse, which nevertheless still kept his legs, and, as her assailant rushed towards her with his machete, she leveled a pistol. She sent a ball through one of his legs, breaking it and bringing him to the ground. Dismounting from her horse, which was reeling and staggering with loss of blood, she held her other pistol to the head of the prostrate guerrilla, who surrendered at discretion.

Meanwhile, the guide had dispatched one of the two remaining Mexicans, and though he had a shot in the fleshy part of his leg, he had succeeded in compelling the other to surrender by shooting his horse.

Mrs. Coolidge now, for the first time, discovered blood dripping from a wound made by a musket ball in her bridle arm. Hastily winding her scarf about it, she bound the arms of her prisoner with a piece of rope and broke his lance and the locks of his pistols and carbine. The other prisoner was served in the same fashion. The arms of the two dead Mexicans were also broken or disabled. Mrs. Coolidge took the fleetest and best of the two remaining horses instead of her gallant little mustang, which was now gasping out his life on the rocky bottom of the pass. Our gallant couriers then paroled the two prisoners and galloped rapidly down the cañon, taking the other mustang with them and leaving the guerrillas to find their way home as they best might. As they mounted their horses, the guide remarked to Mrs. Coolidge that he had previously entertained the suspicion that she might be a woman but that now he knew she was a man.

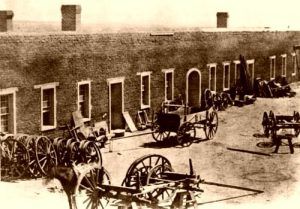

Fort Union, New Mexico.

A swift ride brought them to old Pecos, a distance of 10 miles, where they supped and passed the night. Their wounds were mere scratches and did not necessitate any delay, and the next day, after a long, slow gallop, they reached Las Vegas. Then, keeping their course to the northwest and pushing rapidly forward, they passed the present site of Fort Union and, having secured a large supply of dried buffalo meat, crossed the wonderful mesa or table-land west of the Canadian River and encamped for a night and day on the east bank of that stream.

The next stretch for two hundred miles lay through a country infested with Ute and Apache Indians. Three or four days of swift riding would carry them through this dangerous region to a place of security on the Arkansas River. If they should meet a hostile band, it was agreed that they would trust for safety in the swiftness of their steeds, which had already proved themselves capable of both speed and endurance.

They had crossed Rabbit Ear Creek and reached the Cimarron River without seeing even the sign of a foe when, early one morning, the guide, looking eastward over the vast sandy plain from the camp where they had passed the night, saw far away from a body of 50 mounted Indians, whom, after examining with his glass, he pronounced to be Ute coming rapidly towards them. There was no escape, and, in accordance with their program, they mounted their horses and rode slowly to meet them.

The Indians, spying on them, formed a semicircle and galloped towards the fearless couple, who put their horses to a canter and, riding directly against the center of the line of warriors, dashed through it on the run. The Indians, quickly recovering from the astonishment produced by this daring maneuver, wheeled their horses and dashed after them. All but ten of the Indians were soon distanced; these ten continued the pursuit, but in an hour and a half, this number was reduced to seven, and in another hour, only five remained. They were young braves who were hoping to distinguish themselves by taking two American soldiers’ scalps.

On they sped — the pursuers and the pursued — over the wild plain. A space of barely half a mile divided them. The horses, however, of each party seemed so evenly matched in speed and endurance that neither gained on the other. The mustangs, the one ridden by our heroine, the other with only a 90-pound pack on its back, though glossy with sweat, and their nostrils crimson and expanded with the terrible strain upon them, showed no sign of flagging. The guide’s horse, a heavier animal, began at length to show symptoms of fatigue. If there had been time, he would have shifted his saddle on the pack-mustang, but this was not to be considered. By dint of spurring and lashing the smoking flanks of the now drooping steed, he barely kept his place by his companion’s side.

They were now near a small creek, an affluent of the Arkansas River, when the guide, turning his eyes, saw that only three of the Indians were on their trail. The two others were galloping slowly back. Just as he announced this fact to Mrs. Coolidge, his tired horse fell heavily, throwing him forward upon his head and stunning him senseless.

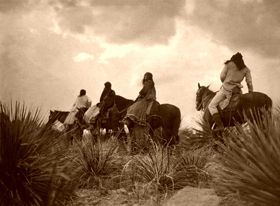

Apache Before the Storm, Edwards S. Curtis, 1906.

Our heroine, dismounting, dragged her unconscious comrade to the bank of the creek and, throwing water in his face, quickly restored him to his senses; but, before he could handle his gun, the Indians had come within a hundred paces, whooping fiercely to call back their companions, who just before abandoned the pursuit. They were luckily only armed with bows and arrows, and, circling about the fearless pair, they launched arrow after arrow without doing any execution. One of them fell before Mrs. Coolidge’s rifle. A second was brought to earth by the guide, who had by this time revived sufficiently to join in the fight. The third turned and galloped off towards his two companions, who were now hastening to the scene of conflict.

This gave our heroine and her associate in danger time to reload their rifles and shield their horses behind the bank of the creek. Then, lying prostrate in the grass, they completely concealed themselves from sight. The three Indians, seeing them disappear behind the bank of the creek and supposing that they had taken to flight again, rode unguardedly within range and received shots that tumbled two of them from their saddles. The only remaining warrior gave up the contest and galloped away, leaving his comrades dead on the field. One of the Indian mustangs supplied the place of the guide’s horse, which was windbroken, and the two now pursued their journey at a moderate pace, reaching Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, without encountering any more dangers.

Leavenworth City grew up around Fort Leavenworth, which had been established years earlier in 1827.

Mrs. Coolidge (under her pseudonym of James Brown), after delivering her dispatches, was promoted to the rank of sergeant and was, at her request, detached from the New Mexican division of the army and ordered to Matamoras, where she did garrison duty without any suspicion being awakened as to her sex. She afterward entered active service and accompanied the army on the march to the city of Mexico. She took part in the storming of Chapultepec and never flinched in that severe affair, covering herself with honor and proving what brave deeds a woman can do in the severest test to which a soldier can be put.

During the recent war between the North and the South, women’s position on the frontier was similar to that of the women who had occupied it in the War of 1812. The greater part of the army of the United States, which, in time of peace, was stationed along the vast borderline from the Red River of the North to the Rio Grande, had been withdrawn. The outposts, which the blood-thirsty Sioux, Comanche, Apache, and numerous other fierce and warlike tribes had been kept in check, were either abandoned or so poorly garrisoned that the settlements upon the border were left almost entirely unprotected from the treacherous savage, the lawless Mexican bandit, and the American outlaw and desperado.

What made their position still more unguarded and dangerous was the absence of their fathers, husbands, and brothers as volunteers in the armies. The war fever raged in the North and the South and was nowhere hotter than among the pioneers from Minnesota to Texas. This brave and hardy class of men, accustomed as they were to the presence of danger, obeyed the call to arms with alacrity, and the women appear to have acquiesced in the enlistment of their natural protectors, trusting to God and their arms to guard the household during the absence of the men of the family.

Thus, the women were left alone to face their human foes and the thousand other perils that beset them. They were, to all intents and purposes, soldiers. They belonged to the home army, upon which the frontier would have mainly to rely for security. Ceaseless vigilance by night and day and steady courage in the presence of danger had to be constantly exercised.

Sometimes, the savage foe came in overwhelming numbers. In such cases, the only safety lay in flight, during which all woman’s address and fortitude were called into requisition, either to devise means of successfully eluding her pursuers or to endure the toils and hardships of a rapid march. Sometimes, she stood with a loaded gun in her household garrison and faced the enemy, either repelling them, or dying at her post, or, what was worse than death, seeing her loved ones butchered before her eyes and their being led into cruel captivity.

On the Texas border in 1862, one of these home warriors, during her husband’s absence in the Southern army, was left alone not far from the Rio Grande and ten miles from the house of any American settler. Three Mexican horse thieves came to the house and demanded the key to the stable, in which two valuable horses were kept, threatening, in case of refusal, to burn her house over her head. She stood at her open door with a loaded revolver and told them that not only would she not surrender the property but that the first one who dared to lay violent hands upon her should be shot down. Cowed by her intrepid manner, the bandits slunk away.

On another occasion, she was attacked by two American outlaws while riding on the river bank. One seized the horse’s bridle, and the other attempted to drag her from the saddle. Turning upon the latter, she shot him dead, and the other, from sheer amazement at her daring, lost his self-possession and begged for mercy. After compelling him to give up his arms, she allowed him to depart unmolested, as there was no tribunal of justice nearby where he could be punished for his villainy. These exploits gained the borderer’s wife a wide reputation throughout the region, and either through fear of her courage or through admiring respect for such heroism, when displayed by a lone woman, she was never again troubled by marauders.

Sioux War in Minnesota, by Henry August Schwabe, 1902.

The Sioux War in Minnesota in 1862 was remarkable for the sufferings endured and the bravery displayed by women whose husbands had left them to join the army.

A notable instance of this description was two married sisters who lived in one house on the Minnesota River, some eighty miles above Mankato. One morning in the spring of that year, their house was surrounded by Sioux Indians but was so bravely defended that the savages withdrew without doing much damage. Two weeks of perfect peace passed away, and the two sisters renewed their outdoor work as fearlessly as ever, as their secluded situation prevented them from hearing of the ravages of the Indians in the eastern settlements.

Late one afternoon, while both the women were sitting in a small grove not far from the house, they heard the war-whoop and, stealing through the bushes, saw ten savages who had dragged the three children from the house and cut their throats and, after scalping them, were dancing about their mangled corpses. They then set fire to the house and barns and, butchering the cow, prepared a great feast.

Not knowing how long the Indians would remain and having no food nor means to procure any, the unfortunate women set out for the nearest house, situated ten miles to the east. ThEastucceeded in reaching the spot at ten o’clock that night but found nothing but a heap of ashes and two mangled bodies of a woman and her child.

Grief, fear, and fatigue kept them from obtaining that rest they so needed, and before daylight, they resumed their march towards the next house, eight miles farther east. This had also been destroyed. The younger sister, the mother of the three children who had been butchered, now gave up in grief and despair and declared that she would die there. But she was at length induced to proceed by the urgent persuasions of the older and stronger woman.

The river’s borders at this point were covered with woods rendered impervious to the sun’s rays by the herbs and shrubs that crept up the trunks and twined around the branches of the trees. They resumed their melancholy journey, but observing that following the course of the river considerably lengthened their route, they entered the wood and lost their way in a few days. Though now nearly famished, oppressed with thirst, and their feet sorely wounded with briars and thorns, they pushed forward through immeasurable wilds and gloomy forests, drawing refreshment from the berries and wild fruits they could collect. At length, exhausted by hunger and fatigue, their strength failed them, and they sunk down helpless and forlorn. Here, they waited impatiently for death to relieve them from their misery. In four days, the younger sister expired, and the elder continued to stretch beside her sister’s corpse for 48 hours, deprived of using all her faculties.

At last, Providence gave her strength and courage to quit the melancholy scene and attempt to pursue her journey. She was now without stockings, barefooted and almost naked; two cloaks, which had been torn to rags by the briars, afforded her but a scanty covering. Having cut off the soles of her sister’s shoes, she fastened them to her feet and went on her lonely way. On the second day of her journey, she found water and, the day following, some wild fruit and green eggs, but so much was her throat contracted by the deprivation of nourishment that she could hardly swallow such a sufficiency of the sustenance which chance presented to her as would support her emaciated frame.

That evening, she was found by a party of volunteers who had been in pursuit of the Indians, and she was brought into the nearest settlement in a condition of body and mind to which even death would have been preferable.

Notwithstanding the dangers and distractions of this quasi-military life led by wives and mothers on the frontier, they did not neglect their other home duties.

When the scarred and swarthy veterans returned to their homes on the border, no marks of neglect were left to be erased, and no evidence of dilapidation and decay. “They found their farms in as good a condition as when they enlisted. Enhanced prices had balanced diminished production. Crops had been planted, tended, and gathered by hands that had been all unused to the hoe and rake before. The sadness lasted only in those households–alas! too numerous–where no disbanding of armies could restore the soldier to the loving arms and the blessed industries of home.”

During the late war, these women of the frontier may have been called the irregular forces of the soldiers in all respects except when they were enrolled and placed under officers. They fought and marched, stood on guard, and were taken prisoners. They viewed the horrors of war and were under fire, although they did not wear the army uniform nor walk in files and platoons. All these things they did in addition to their work as housewives, farmers, and mothers.

Many others took naturally to the rough life of a soldier, and enlisting under soldiers’ guise followed the drum on foot or in the saddle and encamped on the bare ground with a knapsack for a pillow and no covering from the cold and rain but a brown army blanket.

One of these heroines was Miss Louisa Wellman of Iowa. Born and nurtured on the border, habituated from childhood to outdoor life, a fine rider, as well as a good shot with both a rifle and a pistol, it was quite natural that she should have felt a martial ardor when the war commenced, and having donned her brother’s clothes should have enlisted as she did in one of the Iowa regiments. Her most serious annoyance was the rough language and profanity of the soldiers. While in camp, she managed to associate with the sober and pious soldiers, several of whom were in the company. This was afterward known as “the praying squad.” Still, she did not lose her popularity due to her reluctance to associate with others, owing to her unvarying cheerfulness, generosity, and disposition to oblige often at the greatest inconvenience to herself. If a comrade was taken sick, she was the first to tender her services as a watcher and nurse, and in this way, she became known as “Doctor Ned.”

Battle of Fort Donelson, Tennessee, by Kurz and Allison, 1887.

She took part in the storming of Fort Donelson, Tennessee, where she was slightly wounded in the wrist. Afterward, she often served in the picket line and distinguished herself by courage, vigilance, and shrewdness. The boldness with which she exposed herself on every occasion led to such a catastrophe as might have been expected. The Battle of Shiloh was an affair in which she figured with cool bravery that kept her company steady despite the terrible fire decimating the ranks of the Federal Army. The pressure, however, was at last too great. Slowly driven towards the river and fighting every inch of ground, the regiment she served seemed likely to be annihilated. They had just reached the shelter of the gunboats when a stray shell exploded directly in the faces of the front rank, and Miss Wellman was struck and thrown violently to the earth but instantly sprang to her feet and was able to walk to the temporary hospital which had been established near the river bank.

Like Deborah Samson, her sex was discovered by the surgeon who dressed her wound. The wound was in the collarbone and was made by a fragment of shell. Although not a dangerous one, it required immediate attention. When the surgeon desired her to remove her army jacket, she demurred, and not being able to assign any good reason for her refusal, the surgeon coupled this with the modest blush that suffused her features when he made his requisition for the removal of her outer garment, immediately guessed the truth. With chivalrous delicacy, he immediately dispatched her with a note to the wife of one of the Captains who was in the camp at the time, recommending the maiden soldier to her care and begging that she would dress the wound according to a prescription he sent. Although Miss Wellman begged that her secret might not be disclosed and that she might be permitted to continue to serve in the ranks, it was judged best to communicate the fact to the commanding officer, who, though he admired the bravery and resolution of the maiden, judged best that she should serve in another capacity if at all, and having notified her parents and obtained their consent she was allowed to do service in the ambulance department.

Side saddle.

She was furnished with a horse, side saddle, saddlebags, etc.; whenever a battle occurred, she would ride fearlessly to the front to assist the wounded. She assisted many poor wounded soldiers off the field, and sometimes she would dismount from her horse and, aiding the wounded man in climbing into the saddle, would convey him to the hospital. She carried bandages and stimulants in her saddlebags and did all she could to relieve the sufferings of such as were too severely wounded to be removed.

During this service, she was often exposed to the enemy’s fire. She was with General Ulysses S. Grant in the Vicksburg campaign, and on one occasion, being attracted by a tremendous firing, she rode rapidly forward and, missing her way, found herself within one hundred yards of a battalion of the enemy, whose gray jackets could be seen through the smoke of their rapid firing. Wheeling her horse, she galloped out of range, fortunately escaping the storm of bullets that flew about her.

She shared the hardships and perils of the soldiers and, in the bivouac, wrapped herself in her blanket and lay on the bare ground, with no other shelter but the sky, rising at the sound of reveille partake with her comrades of the plain camp fare. All this she did cheerfully and with her whole heart. Her sympathy was not bounded by the wants and sufferings of the federal army soldiers but embraced in its boundless outpouring those of her countrymen who were then ranged against her as foes. Many a sick and suffering Southerner had cause to bless the kindness and devotion of this noble girl. Herein, she showed herself a Christian woman and a practical example of the teachings of Him who said, –“Love your enemies.” Such deeds as hers shine amid the terrible passions and carnage of war with a heavenly radiance that time can never dim.

Either in the army or in close connection with it, a woman’s affectionate devotion was illustrated in all those relations of life in which she stands beside the man. As a mother, as a wife, and as a sister, she brightly displayed this quality. The following instance of wifely devotion is related to a woman from the Red River of Louisiana with her Southern officer husband.

In the fall of 1863, during the bombardment of Charleston by the federal batteries, this young woman, being tenderly attached to her husband, who was in one of the forts, begged the military authorities to allow her to join her husband and share the fearful dangers and hardships to which he was daily and nightly exposed. All representations of the difficulties, privations, and perils she would encounter failed to daunt her in her purpose. The persistence of the loving wife prevailed over military rules and even over the expostulations of her husband, and she was allowed to take her post beside the one she regarded with an affection amounting to idolatry. Sending her two children to the care of a maiden aunt some miles from the city, she was conveyed to her husband’s battery, a large earthwork outside of the city.

Here, she remained for 60 days, during which the battery where she was made one of the principal targets for the federal cannon. For weeks together, she lay down in her clothes amid the soldiers. The bursting of the shells and the sound of the federal hundred-pounders, with answering volleys from the fort, scarcely intermitted night or day. Sleep was out of the question for several days after her arrival. But at length, she became used to the cannonade and enjoyed intermittent slumbers, from which she was sometimes awakened by the explosion of a shell that had penetrated the roof of the fort and strewed the earth with dead and wounded.

Her only food was the wormy bread and half-cured pork served out to the soldiers, and her drink was brackish water from the ditch that surrounded the earthwork. The cannonading during the day was so furious that the fort was often almost reduced to ruins, but in the night, the destruction was repaired. A fleet of gunboats joined the land batteries in bombarding the fort, finally making it no longer tenable. Guns had been dismounted, the bomb-proof had been destroyed, and the sides of the earthwork were full of breaches where the huge ten-inch balls had plowed their way.

During all these terrifying and dreadful scenes, our heroine stayed beside her husband at her post of love and duty. When the little garrison evacuated the fort at night and retired to the city, she was carried in an ambulance drawn by four soldiers in honor of her courage and devotion.

One of the most singular and romantic stories of the late war is that of two young women who enlisted at the same time and were engaged in active service for nearly a year without any discovery being made or even suspicion as to their true sex.

Sarah Stover and Maria Seelye were the names of these real-life heroines; being homeless orphans and finding it difficult to earn a subsistence on a small farm in Western Missouri, where they lived, they determined to enlist as volunteers in the Federal Army. Accordingly, having donned male attire and proceeded to St. Louis early in 1863, they joined a company that was soon after ordered to proceed to the regiment, which was a part of the Army of the Potomac.

Within two weeks after they arrived at the scene of conflict in the East of Chancellorsville, it was fought, and the two girls participated in it and saw something of the horrors of the war in which they were engaged as soldiers. In one of the minor battles that occurred the following summer, they were separated in the confusion of the fight, and upon calling the muster, Miss Stover, known in the regiment as Edward Malison, was found among the missing. Her comrade, after searching for her among the killed and wounded in vain, at last, ascertained that she had been taken prisoner and conveyed to Richmond, Virginia.

Although she was well aware of the serious consequences that might follow, Miss Seelye decided to adopt a bold plan to reach her friend whom she loved so devotedly and who was now suffering captivity and perhaps wounds or disease. She obtained a woman’s dress and bonnet through an old black woman and, disguising herself in these garments, deserted at the first favorable opportunity. She reached Washington safely and successfully applied for a pass to Fortress Monroe, from which place she made her way after many difficulties to the lines of the Southern Army. By artful representations, she overcame the scruples of the officers and passed on her way to Richmond, where she soon arrived, and overcoming by her address and perseverance all obstacles, obtained admission to Libby Prison, representing that she was near to kin to one of the prisoners.

Her singular success in accomplishing her object was doubtless due to her intelligence, fine manners, and good looks, as well as her great tact in using the opportunities within her reach.

Battle of Chancellorsville, Kurz, and Allen.

She found her friend just recovering from a wound in her arm. The secret of her sex was still undiscovered, and after her wound was entirely healed, they prepared to attempt an escape they had already planned. Miss Seelye contrived to smuggle into the prison a complete suit of female attire, in which, one night, just as they were relieving the guard, she managed to slip past the cordon of sentries and join her friend at the place agreed upon, the two immediately set out for Raleigh. To that city, Miss Seelye had obtained two passes, one for herself, the other for a lady friend. They traveled on foot and, after passing the lines, struck boldly across the country toward Norfolk. When morning dawned, they concealed themselves in the woods and, at night, resumed their march.

On one occasion, just as they were emerging from a wood in the evening, they were discovered by a cavalryman. Their appearance excited his suspicions that they were spies, and he told them that he should have to take them to headquarters. But their lady-like manners and straightforward answers persuaded him that he was wrong, and he allowed them to proceed. Another time they narrowly escaped capture by two soldiers who suddenly entered the cabin of an old negro where they were passing the day.

After a tedious journey of a week, they reached the Federal pickets and finally were transported to Washington on the steamer. This was in the autumn of 1863; their term of service would expire in two months, but after great hesitation, they resolved to report themselves to the headquarters of their regiment as just escaped from Richmond. Accordingly, procuring suits of men’s attire, they again disguised their sex and rejoined their regiment, which was encamped near Washington.

Having been explained in this manner, Miss Seelye’s desertion caused her to escape its serious penalty, and both the girls were soon after regularly discharged from service. As we have already remarked, no suspicion was excited as to their sex, each shielding the other from discovery, and it was only after their discharge that they revealed the secret.

The stories of women who have served as soldiers often disclose motives that would have little influence in impelling the other sex to enter the army. Love and devotion are among the most prominent of the moving causes of female enlistment. Sometimes, a maiden, like Helen Goodridge, followed her lover to the war; sometimes, a mother enlisted in the hospital department to nurse a wounded or sick husband or son. It was often some species of devotion, either to individuals or to her country, that led gentlewomen to march in the ranks and share the dangers and privations of army life. Such an instance as the following furnishes a singularly striking illustration of the unselfish love and devotion we are speaking of.

While the hostile armies were fighting, in the summer of 1864, those desperate battles by which the issues of the war were ultimately decided, a small, slender soldier fighting in the ranks in General Johnson’s division was struck by a shell which tore away the left arm and stretched the young hero lifeless on the ground. A comrade in pity twisted a handkerchief around the wounded limb as an impromptu tourniquet and, thus having staunched the flowing blood, placed the slender form of the unfortunate soldier under a tree and passed on. Half an hour later, he was found by the ambulance men and brought to the hospital, where the surgeon discovered that the heroic heart, still faintly beating, animated the delicate frame of a woman.

Powerful stimulants were administered, and as soon as strength was restored, the stump of the wounded limb was amputated near the shoulder. For a week, the patient hovered between life and death. But her vitality triumphed in the struggle, and in a few days, with careful nursing, she could sit up and converse. One of those noblewomen who emulated the example and the glory of Florence Nightingale in nursing and ministering to the sick and wounded in the army won the maiden-soldier’s confidence. Into her ear, she breathed her story.

Civil War Guns

She and a brother, aged 18, had been left orphans two years before. They were in destitute circumstances and had no near relations. They both supported themselves with honest toil, and their lonely and friendless situation had drawn them together with a warmth of affection that was rarely felt between a brother and sister. They were all in all to each other, and when, in the spring of 1864, her brother had been drafted into the army, she learned the name of the regiment to which he had been assigned and, unknown to him, assumed male attire and joined the same regiment.

She sought out her brother and, in a private interview, made herself known to him. Astonished and grieved at the step she had taken, he begged her to withdraw from the army, which she could easily do by disclosing the fact of her true sex. She remained firm against all his affectionate entreaties, informing him that if he were wounded or taken sick, she would be near to nurse him. In case of such a disaster, she would reveal her secret and get a discharge to attend to him constantly. On the morning of the battle in which she had been wounded, they had met for the last time and, as they knew the battle would be bloody, agreed that each one would notify the other of their respective safety in case they both survived. A note had reached her just after the battle that her brother was safe, and she, on her part, had told him that she was alive and well, believing that she would recover and not wishing to alarm him by telling the truth. Since that time, she had heard nothing from him and begged with streaming eyes that the lady would inquire if he had been wounded in any of the recent severe battles. The lady hastened to procure the much-desired information. After diligent inquiries, she discovered that the brother had been shot dead in a battle that occurred the day after his sister had been wounded.

The good lady, sadly afflicted by this intelligence and fearing its effect upon the invalid, strove to assume a cheerful countenance as she approached the couch. A smile of almost painful sweetness shone on the face of the girl soldier when she first glanced at the serene face of the lady who kindly put her off in her penetrating inquiries but could not avoid showing a trace of grief and anxiety over the sad message with which she was burdened.

The smile slowly faded from the girl’s face; her voice grew tremulous, her questions more searching and direct. The lady tried to gently tell the sad truth to her, but the unfortunate maiden had already comprehended the fact. Her face grew a shade paler, then flushed; she breathed with difficulty. They raised her, a crimson stream gushed from her lips, and an instant after, the strong heart of the true and loving sister was still forever.

William Fowler, 1877. Compiled and edited Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated April 2024.

About the Author: William Worthington Fowler was a diverse man with several careers, including lawyer, stockbroker, politician, and author. This article was a chapter of his book Woman On The American Frontier: A Valuable And Authentic History, initially published in 1877. However, the text as it appears here is not verbatim; it has been edited for clarity and ease of the modern reader.

Also See: