The National Road – First Highway in America – Legends of America (original) (raw)

By the early 19th Century, the wilderness of Ohio had given way to settlement. The road that George Washington had cut through the forest many years before called the Braddock Road, was replaced by the National Road.

Cutting an approximately 820-mile-long path through Illinois, Indiana, Maryland, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia, it was built between 1811 and 1834 and was the first federally funded road in U.S. history. Presidents George Washington and Thomas Jefferson believed a trans-Appalachian road was necessary to unify the young country. On March 29, 1806, Congress authorized the construction of the road, and President Thomas Jefferson signed the act establishing what was first called the Cumberland Road that would connect Cumberland, Maryland, to the Ohio River.

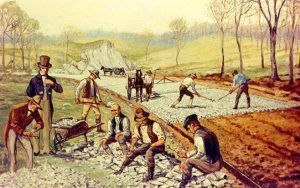

Building the National Road.

The contract for the construction of the first section was awarded to Henry McKinley on May 8, 1811, and construction began later that year, with the road reaching Cumberland, Maryland, and Uniontown, Pennsylvania, in 1817. It was completed to the Ohio River at Wheeling, West Virginia, on August 1, 1818, and mail coaches began using the road. Wheeling would remain its western terminus for several years. Eventually, the road was pushed through central Ohio and Indiana, reaching Vandalia, Illinois, in the 1830s. At that time, it became the first road in the U.S. to use the new macadam road surfacing. During that decade, the federal government conveyed part of the road’s responsibility to the states through which it runs. Tollgates and tollhouses were then built by the states. Plans were made to continue the road to St. Louis, Missouri, at the confluence of the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers and to Jefferson City upstream on the Missouri River. However, following the panic of 1837, funding ran dry, and construction was stopped, leaving the terminus at Vandalia, Illinois.

The opening of the National Road saw thousands of travelers heading west over the Allegheny Mountains to settle the rich land of the Ohio River Valley. It also became a corridor for moving goods and supplies. Small towns along the National Road’s path began to grow and prosper with the increase in population. Towns such as Cumberland, Maryland; Uniontown, Brownsville, and Washington, Pennsylvania; and Wheeling, West Virginia, evolved into commercial centers of business and industry. Uniontown was the headquarters for three major stagecoach lines, which carried passengers over the National Road. Brownsville was a center for steamboat building and river freight hauling on the Monongahela River. Many small towns and villages along the road contained taverns, blacksmith shops, and livery stables.

Thomas Searight remembered as many as 20 stagecoaches in a line on the road at one time. Another man named Jesse Peirsol, a wagoner, remembers a night at a tavern when 30 six-horse teams were parked in the wagon yard, 100 mules were in a pen, 1,000 hogs were in an enclosure, and as many cattle were in the field.

Mount Washington Tavern, Uniontown, Pennsylvania, 1933.

Taverns were probably the most important and numerous businesses on the National Road. It is estimated there was about one tavern on every mile of the road. There were two classes of taverns, including the stagecoach tavern, which was more expensive and designed for the affluent traveler, and the wagon stand, which was more affordable for most travelers. The Mount Washington Tavern, which still stands in Uniontown, Pennsylvania, as part of Fort Necessity National Battlefield, was a stagecoach tavern. Regardless of class, all taverns offered three basic things: food, drink, and lodging.

During the heyday of the National Road, traffic was heavy throughout the day and into the early evening. Almost every kind of vehicle could be seen on the road. The two most common vehicles were the stagecoach and the Conestoga wagon. Stagecoach travel was designed with speed in mind and would average 60 to 70 miles in one day. The Conestoga wagon was the “tractor-trailer” of the 19th Century. Conestogas were designed to carry heavy freight. They were often brightly painted with red running gears, Prussian blue bodies, and white canvas coverings. A Conestoga wagon, pulled by a team of six draft horses, averaged 15 miles daily.

The height of the National Road’s popularity came in 1825 when it was celebrated in song, story, painting, and poetry. During the 1840s, popularity soared again as westbound travelers and drovers crowded the inns and taverns. Massive Conestoga wagons hauled produce from frontier farms to the East Coast, returning with staples such as coffee and sugar for the western settlements. Thousands moved west in covered wagons, and stagecoaches traveled the road keeping to regular schedules.

In 1848, Robert S. McDowell counted 133 wagons pulled by six-horse teams that passed along the National Road in one day. He took “no notice of as many more teams of one, two, three, four, and five horses.

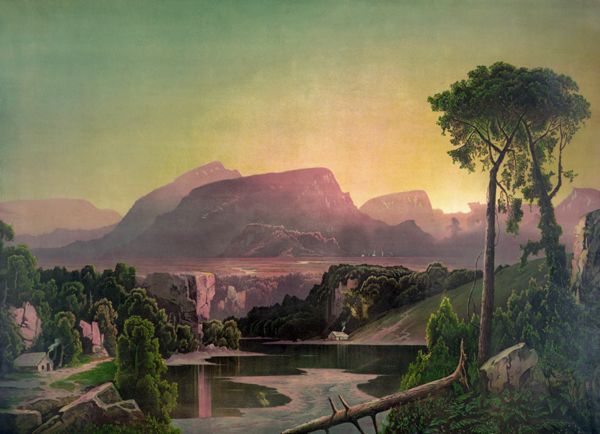

Sunrise in the Alleghenies, Gibson and Co, 1880.

By the early 1850s, technology was changing the way people traveled. The steam locomotive was being perfected, and soon, railroads would cross the Allegheny Mountains. The people of Southwestern Pennsylvania fought vigorously to keep the railroad out of the area, knowing its impact on the National Road. However, in 1852, the Pennsylvania Railroad was completed to Pittsburgh, and shortly after, the B & O Railroad reached Wheeling, West Virginia. This spelled doom for the National Road, as the traffic quickly declined, and many taverns went out of business.

An article in Harper’s Magazine in November 1879 declared:

“The national turnpike that led over the Alleghenies from the East to the West is a glory departed… Octogenarians who participated in the traffic will tell an enquirer that never before was there such landlords, such taverns, such dinners, such whiskey… or such endless cavalcades of coaches and wagons.”

A poet lamented, “We hear no more the clanging hoof and the stagecoach rattling by, for the steam king rules the traveled world, and the Old Pike is left to die.”

National Old Trails Road in Colorado.

In 1912, the pathway became part of the National Old Trails Road. Just a few years later, just as technology caused the National Road to decline, it also led to its revival with the invention of the automobile in the early 20th Century. As “motor touring” became popular, the need for improved roads grew. Many early wagon and coach roads, such as the National Road, were revived into smoothly paved automobile roads. The Federal Highway Act of 1921 established a program of federal aid to encourage the states to build “an adequate and connected system of highways, interstate in character.” In 1926, the grid system of numbering highways was in place, thus creating U.S. Route 40 out of the ashes of the National Road.

This spurred a generation of new businesses — stage taverns and wagon stands were replaced by hotels, motels, restaurants, and diners. The service station replaced the livery stables and blacksmith shops. With the influx of new businesses, some National Road-era buildings regained new life. Route 40 was a major east-west artery until the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956 created the interstate system. Much of the traffic was diverted away, and interest in the National Road again waned.

Decades later, however, new generations are finding these older two-lane roads a more relaxing journey and are again enjoying the history. Today, the old pavement is a National Scenic Byway where visitors can experience a physical timeline, including classic inns, tollhouses, diners, and motels that trace 200 years of American history. Cameras capture old buildings, bridges, and stone mile markers along this historic path. Old brick schoolhouses from early years sporadically dot the countryside; some are found in the small towns on the National Road. Many are still used, some are converted to a private residence, and others stand abandoned.

Numerous sites on the National Road are listed on the National Register of Historic Places. A few of these include:

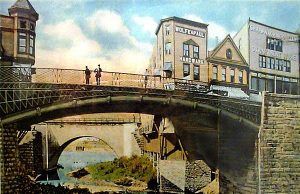

Dunlap’s Creek Bridge, Brownsville, Pennsylvania.

- Casselman River Bridge near Grantsville, Maryland.

- Near Brownsville, Pennsylvania, Dunlap’s Creek Bridge was the first cast-iron arch bridge in the United States, completed in 1839.

- Huddleston Farmhouse Inn in Mount Auburn, Indiana.

- James Whitcomb Riley House in Indiana.

- National Road Corridor Historic District in Wheeling, West Virginia.

- Old Stone Arch, National Road, near Marshall, Illinois.

- Petersburg Tollhouse in Addison, Pennsylvania.

- The Red Brick Tavern in Lafayette, Ohio, was built in 1837.

- Road Segment of the road in Cambridge, Ohio.

- Searight’s Tollhouse, National Road, in Uniontown, Pennsylvania.

- S Bridge in Washington County, Pennsylvania, near Washington, Pennsylvania.

- Wheeling Suspension Bridge in Wheeling, West Virginia.