Settling America – The Proprietary Colonies – Legends of America (original) (raw)

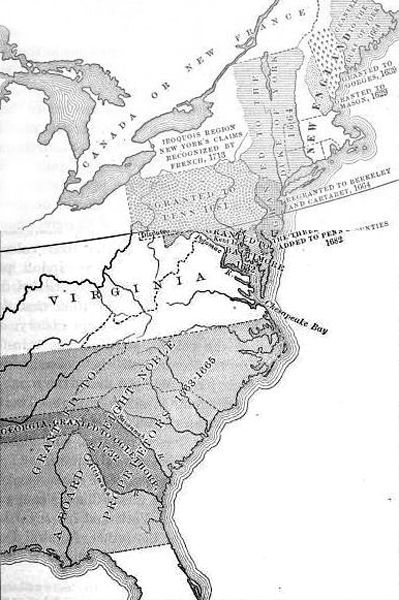

Proprietor Grants

By David Saville Muzzey, 1920

Of the 13 colonies that later united to form the United States, all except Virginia and the New England settlements were founded as proprietorships. The Proprietorship was a sort of middle thing between the royal province and the self-governing colony. The king let the reins of government out of his own hands but did not give them into the hands of the colonists. Between the king and the settlers stood the proprietor, a man or a small group of men, generally courtiers, to whom the king had granted the province. The proprietors appointed the governors, established courts, collected a land taxes from the inhabitants, offered bonuses to settlers, and, in general, managed their provinces like farms or any other business venture, subject always to the limitations imposed by the terms of their charter from the king and the opposition of their legislatures in the colonies.

In 1632, George Calvert, also known as Lord Baltimore, a Roman Catholic nobleman high in favor of the court, obtained from King Charles I the territory between the fortieth parallel of north latitude and the south bank of the Potomac River, with a very liberal charter.

The people of Maryland were to enjoy “all the privileges, franchises, and liberties” of English subjects; no tax was to be levied by the crown on persons or goods within the colony; and laws were to be made “by the proprietor, with the advice of the freemen of the colony.” George Calvert died before the king’s great seal was affixed to the charter, but his son, Cecilius Calvert, sent a colony to St. Marys on the shores of Chesapeake Bay in 1634.

James Barry established Religious and civil liberties in Maryland in 1649 in 1793.

The second Lord Baltimore needed all his tact, nobility, and courage to meet the difficulties with which he had to struggle. The tract of land granted to him by King Charles lay within the boundaries of the grant of King James to the Virginia Company. A Virginian fur trader named Claiborne was already established on Kent Island in Chesapeake Bay and refused either to retire or to give allegiance to the Catholic Lord Baltimore. It came to war with the Virginian Protestants before Claiborne was dislodged. Again, Lord Baltimore interpreted the words of his charter to mean that the proprietor was to frame the laws and the freemen to accept them. Still, the very first assembly of Maryland took the opposite view, insisting that the proprietor had only the right to approve or veto laws they had passed. Baltimore tactfully yielded.

Religious strife also played an important part in the troubled history of the Maryland settlement. Lord Baltimore had founded his colony chiefly as an asylum for the persecuted Roman Catholics of England, who were regarded as idolaters by both the New England Puritans and the Virginia Episcopalians. To have Mass celebrated at St. Marys was, in the eyes of the intolerant Protestants, to pollute the soil of America. As Baltimore tolerated all Christian sects in his province, the Protestants simply flooded out the Catholics of Maryland by immigration from Virginia, New England, and old England. Eight years after the colony’s establishment, the Catholics formed less than 25% of the inhabitants. In 1649, the proprietor was obliged to protect his fellow religionists in Maryland by getting the assembly to pass the famous Toleration Act, providing that “no person in this province professing to believe in Jesus Christ shall be in any ways troubled, molested, or discountenanced for his or her religion . . . so that they be not unfaithful to the lord proprietary or molest or conspire against the civil government established.” Although this was the first act of religious toleration on the statute books of the American colonies, we should remember that Roger Williams, thirteen years earlier, had founded Rhode Island on principles of religious toleration more complete than those of the Maryland Act; for Jews or freethinkers would be excluded from Lord Baltimore’s domain. By 1658, the fierce strife between Catholics and Protestants had been allayed, and Maryland settled down to peaceful and prosperous development.

Carolina

King Charles II, who took a great interest in the colonies in the early years of his reign, granted to a group of eight noblemen, in 1663, the huge tract of land between Virginia and the Spanish settlement of Florida, extending westward to the “South Sea” (Pacific Ocean). The charter gave the proprietors powers as ample as Lord Baltimore’s in Maryland. But, the board of proprietors was not equal to Lord Baltimore’s intact energy and devotion to the colony’s interests. The initial mistake was the attempt to enforce a ridiculously elaborate constitution, the “Grand Model,” composed for the occasion by the celebrated English philosopher John Locke, and utterly unfit for a sparse and struggling settlement.

A community grew up on the Chowan River in 1670, founded by some malcontents from Virginia and another on the shore of the Ashley River, 300 miles to the south. The latter settlement was transferred ten years later, in 1680, to the site of the modern city of Charleston, South Carolina.

Colonial Days, James S. King, 1887.

These two widely separated settlements developed gradually into North and South Carolina, respectively. The names were used as early as 1691, but the colony was not officially divided and provided with separate governors until 1711. The history of the Carolinas is a story of inefficient government, of wrangling and discord between people and governors, governors and proprietors, and the proprietors and king. North Carolina was described as “a sanctuary of runaways,” where “everyone did what was right in his own eyes, paying tribute neither to God nor to Caesar.” The Spaniards incited the Indians to attack the colony from the south, and pirates swarmed the harbors and creeks of the coast. Finally, the assembly of South Carolina, burdened by an enormous debt from the Spanish-Indian wars, offered the province’s lands for sale to settlers on its own terms. The proprietors vetoed this action, which invaded their chartered rights. Then, the assembly renounced obedience to the proprietors’ magistrates and petitioned King George I to be taken under his protection as a royal province in 1719. It was the only case in our colonial history of a proprietary government overthrown by its own assembly. Ten years later, the proprietors sold their rights and interests in both Carolinas to the crown for the paltry sum of £50,000. So, two more colonies were added to the growing list of royal provinces.

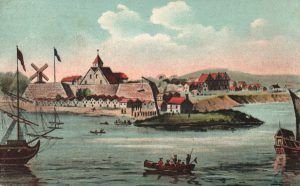

Fort Amsterdam, New York

While the Carolina proprietors were inviting settlers to their new domain, an English fleet sent out by King Charles’ brother, the Duke of York, sailed into New York Harbor and demanded the surrender of the feebly garrisoned Dutch fort on Manhattan Island in September 1664. The fort was commanded by Peter Stuyvesant, director general of the Dutch colony of New Netherland, which had been founded fifty years before and was governed by the Dutch West India Company. The company established fortified trading posts in New Amsterdam (New York City) and Fort Orange (near Albany), but they did not make the colony successful. However, they offered tracts of land eight miles deep along both sides of the river to rich proprietors with feudal privileges of trade and government. In 1638, they abolished all monopolies, opened trade and settlement to all nations, and made liberal offers of land, stock, and implements to tempt farmers. However, even the city of New Amsterdam, with its magnificent commerce situation, reached a population of only 1,600 during the half-century that it was under Dutch rule.

The West India Company, intent on the profits of the fur trade with the Indians of central New York, would not spend the money necessary for the development and defense of the colony. They sent over director-generals who had little concern for the welfare of the people and refused to allow any popular assembly. If the settlers protested that they wanted a government like New England’s, “where neither proprietors, lords, nor princes were known, but only the people,” they were met with the insulting threat of being “hanged on the tallest tree in the land.” Furthermore, the Dutch magistrates were continually involved in territorial quarrels. When Henry Hudson sailed up the majestic river, which bears his name in 1609, he was trespassing on the territory granted by King James I in 1606 to the Plymouth Company. The Dutch disputed the right to the Connecticut Valley with the emigrants from Massachusetts and claimed the land along the lower banks of the Delaware River, from which they had driven out some Swedish settlers by force. In 1653, when England was at war with Holland, New Netherland was saved from the attack of the New England colonies only by the veto of Massachusetts on the unanimous vote of the other members of the Confederation of New England.

The fall of New Amsterdam, J.L.G. Ferris.

Every year the English realized more clearly the necessity of getting rid of the “alien” colony of New Amsterdam, which lay like a wedge between New England and the Southern plantations, controlling the valuable route of the Hudson River and making the enforcement of the trade laws in America impossible. Therefore, in 1664, King Charles II, on the verge of a commercial war with Holland, granted to his brother, the Duke of York, the territory between the Connecticut and Delaware Rivers as a proprietary province. The first the astonished settlers of New Amsterdam knew of this transaction was the appearance of the Duke’s fleet in the harbor, with the court summons to surrender the fort. Director General Stuyvesant, the governor, fumed and stormed, declaring that he would never surrender. But resistance was hopeless. The settlers persuaded the irate governor to yield, although his gunners had their fuses lighted. New Netherland fell without a blow, and the English flag waved over an unbroken coast from Canada to Carolina.

There are still many traces of its 50 years of occupancy by the Dutch in New York. The names of the old Knickerbocker families remind us of the proprietors’ estates, and one still gets glimpses of the high Dutch stoops and quaint marketplaces in the villages along the Hudson River. But, a far more significant bequest of New Netherland to New York was the spirit of absolute government. Under Dutch rule, the people were without a charter or popular assembly, and the new English proprietor was content to keep things as they were, publishing his own code of laws for the province. It was not until 1683 that he yielded to pressure from his own colony and the neighbors in New England and Pennsylvania and granted an assembly. Two years later, when King James II came to the English throne, he revoked this grant and made New York the pattern of absolute government to which he tried to make all the English colonies north of Maryland conform. However, the New York deputy governor, Francis Nicholson, deserted his post and sailed back to England. When a new governor sent by King William III arrived in 1691, he brought orders to restore the popular assembly that King James II had suppressed. From that time on, the colony enjoyed the privilege of self-government.

New York grew slowly. At the time of the foundation of our national government, it was considered a “small state” compared with Massachusetts, Virginia, and Pennsylvania. Years later, its growth would begin with the Erie Canal and the New York Central Railroad, which made the Hudson and Mohawk Valleys the main highway to the Great Lakes and the growing West.

Quaker’s meeting

Even before the Duke of York had ousted the Dutch magistrates from his new province, he granted the lower part of it, from the Hudson River to the Delaware River, to two of his friends, who were also members of the Carolina Board of Proprietors, Lord Berkeley, brother of the irritable governor of Virginia, and Sir George Carteret, formerly governor of the island of Jersey in the English Channel. In honor of Carteret the region was named New Jersey in June 1664.

The proprietors of New Jersey immediately published “concessions” for their colony, — a liberal constitution granting full religious liberty and a popular assembly with control of taxation. In 1674, the proprietors divided their province into East and West Jersey, and from that date to the end of the century, the Jerseys had a turbulent history, despite the fact that both parts of the colony, after various transfers of proprietorship, came under the control of the peace-loving sect of Friends, or Quakers.

New Jersey was put under the royal governor of New York in 1702 and separated again in 1738. There were constant quarrels between proprietors and governors and between governors and legislatures until New Jersey revolted with the rest of the American colonies in the American Revolution.

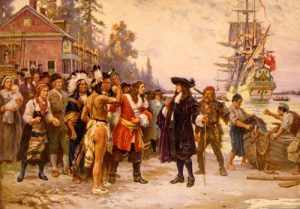

The landing of William Penn, J.L.G. Ferris

One of the Quaker proprietors of West Jersey in the early days was William Penn, a young man high in favor of the Duke of York and his royal brother Charles, on account of the services of his father, Admiral Penn, to the Stuart cause. When the old admiral died, he left a claim for some sixteen thousand pounds against King Charles II. William Penn, attracted by the idea of a Quaker settlement in the New World, accepted from the king a tract of land to pay the debt. He was granted an immense region west of the Delaware River, which he named “Sylvania” (woodland), but which the king, in honor of the admiral, insisted on calling Pennsylvania.

In the meantime, King Charles II was in the midst of a quarrel with the colony of Massachusetts. He was no longer willing to grant proprietors the almost unlimited powers that he had granted to Lord Baltimore and the Carolina proprietors.

The Penn Charter contained provisions that the colony must always keep an agent in London, that the Church of England must be tolerated, that the king might veto any act of the assembly within five years after its passage, and that the English Parliament should have the right to tax the colony. Disappointed that the charter of 1681 gave him no coastline, Penn persuaded the Duke of York in 1682 to release to him the land that the Dutch Director-General of New Netherland had earlier wrested from the Swedes on the Delaware River in 1655.

Despite Lord Baltimore’s protests, the land had been held as a part of New York ever since the English “conquest” of 1664. This territory is called the “Three Lower Counties,” Penn is governed by a deputy. The Lower Counties were separated from Pennsylvania in 1702 and were given their own legislature under the name of the colony of Delaware. Still, they remained a part of the proprietary domain of the Penn family until the American Revolution.

William Penn

Penn offered attractive terms to settlers. The land was sold at ten dollars for 100 acres, complete religious freedom was allowed, a democratic assembly was summoned, and the Delaware Indians, already humbled by their northern foes, the Iroquois were rendered still less dangerous by Penn’s fair dealing with them. Emigrants came in great numbers, especially the Protestants from the north of Ireland, who were annoyed by cruel landlords and oppressive trade laws, and the German Protestants of the Rhine country, against whom Louis XIV of France was waging a crusade. In the first half of the 18th century, the population of Pennsylvania grew from 20,000 to 200,000. Philadelphia, which Penn had planned in 1683, soon outstripped New York in population, wealth, and culture and remained throughout the eighteenth century the leading city in the American colonies. Its neat brick houses, its paved and lighted streets, its printing presses, schools, hospital, asylum, library, philosophical society, and university all testified to the enlightenment and humanity of Penn’s colony and especially to the genius and industry of its leading citizen, the celebrated Benjamin Franklin.

William Penn was the greatest of the founders of the American colonies. He had all the liberality of Roger Williams without his impetuousness, all the fervor of John Winthrop without a trace of intolerance, all the tact of Lord Baltimore with still greater industry and zeal. He was far in advance of his age in humanity. At a time when scores of offenses were punishable by death in England, he made murder the only capital crime in his colony. Prisons generally were filthy dungeons, but Penn made his prisons workhouses for the education and correction of malefactors. His province was the first to raise its voice against slavery in the Germantown protest of 1688, and his humane treatment of the Indians has passed into the legend of the spreading elm and the wampum belts familiar to every American school child. When Penn’s firm hand was removed from the province in 1712, disputes increased between the governor and assembly over taxes, land transfers, trade, and defense. Still, the colony remained in the possession of the Penn family throughout the American colonial period.

The landing of James Oglethorpe in Georgia

Among these proprietorships was also the colony of Georgia, although it was founded long after the Stuart dynasty had given place to the House of Hanover on the English throne. In 1732, James Oglethorpe obtained from the king a charter granting to a body of trustees, for 21 years, the government of that unsettled part of the old Carolina territory lying between the Savannah and Altamaha Rivers. Oglethorpe, who, as chairman of a parliamentary committee of investigation, had been horrified by the condition of English prisons, wished to provide an opportunity for poor debtors and criminals to work out their salvation in the New World. The Church was anxious to convert the Indians on the Carolina borders.

Capitalists expected to profit greatly from the silk and wine industries introduced into the province. The government, drifting already toward the war with Spain, which was declared in 1739, was glad to have the English frontier extended southward toward the Spanish settlement of Florida. So Parliament, the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts, the Bank of England, and many private citizens contributed toward the new colony, which was established on the banks of the Savannah River in 1733 and named Georgia after the reigning king, George II. Slavery was at first forbidden in the new colony, as well as the traffic in rum, which was a disgrace to the New England colonies of Massachusetts and Rhode Island. But, the colony did not prosper. The convicts were poor workers. The industries started were unsuited to the land. Not wine and silk, but rice and cotton, were destined to be the foundation of Georgia’s prosperity. Oglethorpe battled valiantly for his failing colony and defeated the Spaniards on land and sea, but the trustees had to surrender the government to the king in 1752. The founder of the last American colony lived to see the United States acknowledged by Great Britain and the other powers of Europe as an independent nation.

Coloring History by Legends of America. Available at Legends’ General Store.

By David S. Muzzey, 1920. Compiled and edited by Kathy Weiser/Legends of America, updated March 2024.

About the Article: This article was, for the most part, written by David Saville Muzzey and included in a chapter of his book, “An American History,” published in 1920 by Ginn and Co. However, the original content has been heavily edited, truncated in parts, and additional information added.

Also See: