Robert Fulton and the Steamboat – Legends of America (original) (raw)

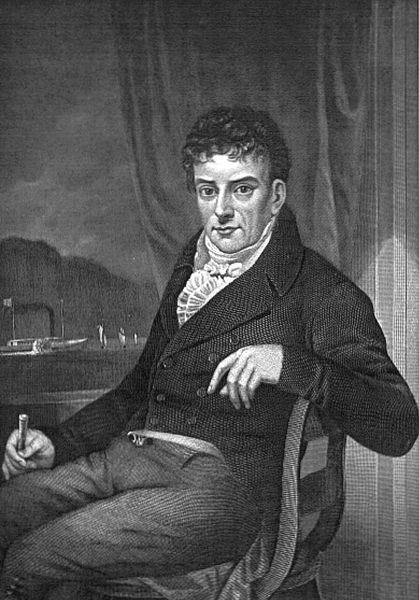

Robert Fulton

By Inez Nellie Canfield McFee in 1913

In Revolutionary times and for many years after, the people’s easiest method of getting about, and carrying their goods from one point to another, was by boats. There were but few roads, and these were sometimes almost impassable due to ruts and mud. Breakdowns and upsets were of everyday occurrence. Passengers frequently had to help the stagecoach driver pull the wheels out of the mud before a journey could be completed. Accidents by water were few, and the going easier and swifter. Dutch sloops and schooners were used considerably on the larger streams in the East, and all kinds of small sailboats and canoes were also in use.

Keelboat, by Jedediah Hotchkiss, 1872

On the western rivers, the flatboat was the most familiar form of craft. It was merely a box, some 50 or more feet in length and about 16 feet wide, and was propelled by long poles. As it was used chiefly to carry produce, it was usually torn to pieces at the end of the journey after its cargo of flour, pork, lumber, molasses, etc., had been sold. Hundreds of these boats went down the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers every year.

The favorite passenger craft was the keelboat. It plied up and down the rivers more or less regularly, being pushed upstream with long poles. Where the current was too strong for this, the boatmen went ashore and hauled the craft along by ropes. Small wonder, then, that one of the problems of the day was to invent a boat that could move along with swiftness and ease and which should not be dependent on the ever-varying wind for its speed.

James Watt, a Scotchman, had so improved the steam engine that people began to hope that steam might be utilized to work for man. Naturally, the thoughts of many inventors turned toward it. Why could not some sort of machinery be devised for applying the power of the steam engine to the movement of boats?

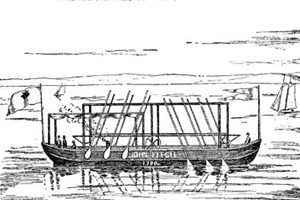

One ingenious Englishman tried to run a boat by making the engine push through the water a device shaped somewhat like a duck’s foot. But it was not a success. In 1730 another Englishman, Dr. John Allen, tried to run a boat by taking in water through an opening in the bow of his boat and then driving it out at the stern with so much force as to push the boat forward. This, too, was a failure. In 1786 John Fitch, an American, built a steamboat and launched it on the Delaware River. His boat was moved using a row of engine-worked paddles arranged along its sides. For more than three months, it plied up and down the river, but it moved so slowly that few passengers cared to ride in it.

Fitch’s Steamboat

Fitch grew ragged and poor and at last, gave up the trips. Three years later, another American by the name of James Rumsey, built a steamboat; but, like Fitch’s boat, but it never became practicable. One inventor after another experimented with the steamboat and failed. People began to think that such a boat could not be built. But two Americans, over in Paris, were not yet ready to give up. These were Chancellor Livingston, the American Minister to France, and Robert Fulton, a young inventor. Both were interested in steam navigation, and they formed a partnership for its promotion. Livingston was to furnish money and advice, and Fulton was to do the work.

Robert Fulton was born in Chester County, Pennsylvania, on November 14, 1765. His father was an Irish tailor. Like many other boys, Young Robert did not care to learn his father’s trade. Neither was he especially interested in books. He was a born inventor and also had considerable talent as an artist. At the age of 17, he was a miniature painter in Philadelphia and succeeded so well that in four years’ time, he was able to buy a little farm for his mother. After seeing her comfortably settled, he sailed for Europe to study art under the direction of Benjamin West.

But his inventive genius continually interfered with his studies. Now and then, he would abandon art and turn out some mechanical invention. One was a submarine torpedo, which he tried in vain to persuade Napoleon to buy. After entering into a partnership with Livingston, he went to England to see a steamboat that William Symington, a Scotchman, had invented. This steamboat had a side-wheel and was fashioned after an idea that Fulton had already in mind. It could make five miles per hour.

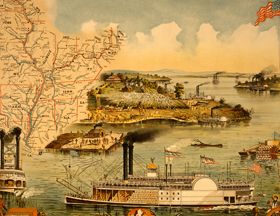

Mississippi River Steamboat

Young Fulton was confident that he could improve on Symington’s model and went back to France full of enthusiasm. The firm immediately built a boat that they launched on the Seine, but it broke into pieces when the engines were placed on board. Fulton proved his determination by immediately building another boat. He was not a man to be disheartened by one failure. The second venture was more successful. He made a trial trip in sight of a large crowd of Parisians. The great Napoleon was deeply interested in the boat. “It is capable of changing the face of the world!” he exclaimed. Notwithstanding all this, the two Americans decided to return to their own country, where the need for steamboats was much more significant.

One of the first things to be done was to get the best engine that could be built. Fulton immediately sent to James Watt for an engine, which was to be fashioned according to his plans. While it was being made, he set about building a steamboat in New York. The Clermont was the name he gave his model. It was the first side-wheel steamboat built in America. It did not appeal to the people at large, who laughed and called it “Fulton’s Folly.” But they assembled in large numbers when it was finally ready, one day in August 1807, to watch it make a trial trip. It was an anxious moment to Fulton, as everyone was sure he would fail; indeed, when the signal was given, the boat moved for a short distance, then it stopped and became immovable. But Fulton hurried below and soon discovered the cause of the trouble. This being easily remedied, the boat went on.

The Clermont made the distance from New York City to Albany, New York (150 miles) in 32 hours and returned successfully. Still, many pronounced it a failure and declared it could not be made to repeat the trip. But it did, and not once, but many times. Then the usefulness of the invention was, at last, appreciated. In 1808, a line of steamboats regularly went up and down the Hudson River, and others were put in operation in various parts of the country.

At first, the steamboat created terror and consternation all along the way. For in those days, newspapers were scarce, and news traveled slowly. Few knew of its existence until the horrid monster “marched by on the tides, lighting its path by the fires it expelled.” This was especially true in the sparsely settled country along the Ohio and the Mississippi Rivers, where many amusing stories were told of the fear it inspired. Some of the vessels were run ashore to escape the terrible creature. The passengers and crews onboard ships that could not get out of the way hid in the hold to escape the dreadful doom that threatened them.

Robert Fulton died in New York in 1815. He lived long enough to see the beginning of the prophecy Napoleon had made concerning his invention. Hundreds of steamboats were already in use in our country alone and would number in the thousands by the early 20th century. Not just like Fulton’s model, to be sure, but built along the same general plan as that which he, in turn, had copied from Symington’s invention. But neither man could ever imagine the great ocean steamers and battleships that have grown out of their seemingly insignificant little boats in his wildest dreams.

In 1909 New York celebrated with a magnificent pageant the centennial of the first trip of the little Clermont, which was the real beginning of steam navigation, and the tricentennial of the discovery of the Hudson River by Henry Hudson.

By I.N. McFee 1913. Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated October 2022.