Zachary Taylor – Distinguished General & President – Legends of America (original) (raw)

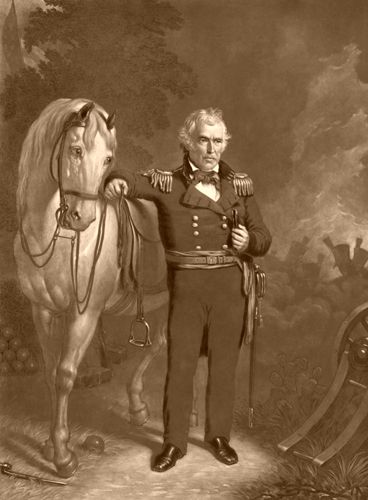

General Zachary Taylor, by John Sartain, 1848.

Based on historic text by Hartwell James, 1899

Zachary Taylor was a distinguished general and the 12th President of the United States. Taylor was born in Orange County, Virginia, on November 24, 1784. His boyhood was spent on his father’s farm while acquiring education at the common schools of the neighborhood. When he was 24 years old, his brother, Hancock, died. He had held a lieutenant’s commission in the army, and Zachary now applied for it, and it was given to him.

In 1810, Taylor was made a captain, and the same year, he wed Margaret Smith. The pair would eventually have six children. His only son, Richard, would grow up to become a lieutenant general in the Confederate Army. One of his daughters, Sarah, would grow up to marry Jefferson Davis, the future President of the Confederate States of America, in 1835.

Taylor did not wish Sarah to marry him, but the wedding took place anyway. However, Sarah would die just three months into the marriage. Taylor and Davis would not get along for more than a decade, only reconciling in 1847 at the Battle of Buena Vista, where Davis distinguished himself as a colonel.

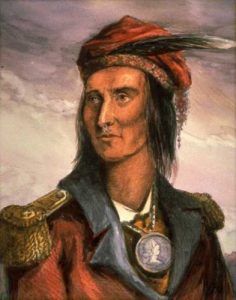

Shawnee Chief Tecumseh

In 1812 Taylor was promoted to major for his brave defense of Fort Harrison near modern-day Terre Haute, Indiana, against the Indian chief, Tecumseh.

As the settlers moved westward, their farms and villages encroached upon the Indian border. The Indians resented the presence of the white man on their lands, and their great chief, Tecumseh, formed a league against the whites. He selected Fort Harrison as a point of attack, and on September 12, 1812, having failed to gain the fort by strategy, commenced a furious assault upon the works. The American sentries gave the alarm a little before midnight, and soon the blockhouse was in flames. Outside were 400 Indians, led by Tecumseh; inside the stockade were only fifty men, of whom 2/3 were disabled by sickness. The scene was one of wild confusion, but Taylor ordered the burning boards stripped from the building. Then earthworks were thrown up, behind which, for seven hours, the little garrison offered such a determined resistance that the Indians were driven away.

In 1814, Taylor fought the combined British and Indian forces on the Rock River in Iowa and Wisconsin during the War of 1812. In 1819, he was a lieutenant colonel in New Orleans, Louisiana. He was made a colonel in 1832. He served in the Black Hawk War, and then, in 1837, he was sent against the unmanageable Seminole Indians, whom he fought so successfully that the campaign’s conduct was placed in his hands. Osceola, the chief of the Seminole, had gathered his braves on the edge of a dense swamp near Lake Okeechobee, Florida, on December 25, 1837. Taylor’s men charged across the marsh that separated them from the Indians and fought the battle knee-deep in the wet, yielding soil. Again and again, the Seminole threw themselves upon the Taylor and his men, but nothing could break the unflinching column before which they were obliged to retire.

General Taylor, Battle of Buena Vista, by Sarony and Major, 1847.

Taylor became a brigadier-general by brevet after the battle and was ordered to the Southwest. The Mexican-American War broke out, and on May 8, 1846, he fought the Battle of Palo Alto, Texas. He had but 2,300 men to oppose a Mexican force of 6,000. The battle opened with artillery and raged furiously. The prairie grass ignited, and dense clouds of smoke obscured the troops. Then the Mexican infantry and cavalry advanced but recoiled and fled. The next day the Mexicans were again routed at the Battle of Resaca de la Palma near Brownsville, Texas, where 1,700 U.S. troops fought some 6,000 Mexicans. In June, Taylor was promoted to the rank of major-general. In September, he captured Monterey, California, after a ten-day siege and three days of hard fighting. Then followed the Battle of Buena Vista, Mexico, in February 1847, where Taylor fought an army four times his size.

Before the engagement, the Mexican commander sent a flag of truce with a summons to surrender. Taylor knew the odds were against him, but his message was: “General Taylor never surrenders.” Then, he turned to his men and said: “I intend to stand here not only so long as a man remains but so long as a piece of a man is left.” Taylor gave his celebrated order in the ensuing battle: “A little more grape, Captain Bragg.” The battle of Buena Vista was a brilliant conflict and a splendid victory for the Americans.

Taylor was beloved by his soldiers, who called him “Old Rough and Ready.” He was strict in discipline but careless about his personal appearance. He seldom appeared in uniform and might easily have been mistaken for a farmer.

In November 1847, Taylor asked permission to return to the United States, tired of the inactive life he was compelled to lead after Buena Vista. He was received with enthusiastic demonstrations everywhere and received many flattering courtesies. Wherever he went, the people made a jubilee. He was elected President in 1848 but would not live to finish his term of office.

The slavery issue dominated Taylor’s short term. Although he owned slaves on his Cypress Grove plantation near Rodney, Mississippi, he took a moderate stance on the territorial expansion of slavery, angering his fellow Southerners. Adding further fuel to the fire, he antagonized the South by advocating the integration of California (a non-slave state).

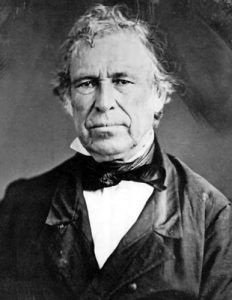

President Zachary Taylor about 1850.

As the Compromise of 1850 was debated, Taylor died of mysterious causes on July 9, 1850. After attending a July 4th celebration at the Washington Monument, he became ill and died five days later. Shortly before his death, he called his wife and asked her not to weep, saying: “I have always done my duty; I am ready to die. My only regret is for the friends I leave behind me.” The cause of death was listed as cholera morbus, as the cholera bacteria frequently occurred during the summer months in Washington, D.C. He was buried at the Taylor Family plot in Louisville, Kentucky.

In the 1920s, the Taylor family initiated efforts to turn the Taylor Family burial grounds into a national cemetery. The State of Kentucky donated two pieces of land for the project, turning the half-acre Taylor family cemetery into 16 acres. Then known as the Zachary Taylor National Cemetery, his wife (who died in 1852) remained until a Taylor mausoleum was commissioned, and they were moved on May 6, 1926.

Years later, in the late 1980s, college professor and author Clara Rising theorized that Taylor was murdered by poison and convinced Taylor’s closest living relative and the Coroner of Jefferson County, Kentucky, to order an exhumation. On June 17, 1991, Taylor’s remains were exhumed and transported to the Office of the Kentucky Chief Medical Examiner; studies were conducted on hair, fingernail, and tissue samples. Though assassination theories had lingered for years, it was concluded that Taylor did, in fact, die of acute gastroenteritis, probably due to the things that he had eaten in the unhealthy climate of Washington, with its open sewers and flies.

Before the exhumation, Rear Admiral Samuel and Official U.S. Navy Historian Eliot Morison theorized that Taylor might have recovered from his illness, but for his doctors’ treatments which included drugging him with ipecac, calomel, opium, and quinine, as well as bleeding and blistering.

Despite the Coroner’s findings, assassination theories still abound, speculating that Taylor was assassinated because of his moderate stance on expanding slavery.

Coloring History by Legends of America. Available at Legends’ General Store.

Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated March 2023.

About the Article: The basis of this article was included in Hartwell James’ book, Military Heroes of the United States from Lexington to Santiago, published in 1899. However, the original article has been heavily edited to include additional information.

Also See:

Presidents of the United States of America