The Long History of Alcatraz Island – Legends of America (original) (raw)

Alcatraz Island in San Francisco, California Bay by Kathy Alexander.

Sitting like a beacon in the middle of the San Francisco Bay of California is Alcatraz Island. Though most prominently known for the years it served as a maximum-security prison, the “Rock’s” history stretches far beyond those infamous days, and its legends and stories continue to find their way into American lore.

~~

Alcatraz Lighthouse by Kathy Alexander.

“Break the rules, and you go to prison. Break the prison rules, and you go to Alcatraz.” — Anonymous

History of Alcatraz

Ohlone Village.

Long before Alcatraz became home to some of the most notorious outlaws in the country, it was known as a place to be avoided by Native Americans who believed it to contain evil spirits. These Native Americans, called the Ohlone (a Miwok Indian word meaning “western people”), often utilized the island as a place of isolation or banishment for members violating tribal laws. Despite the legends of evil spirits, Alcatraz was also used by the Indians as an area for food gathering, especially bird eggs and sea-life.

The first Europeans to visit the island were the Spanish in 1769, who named it “Isla de Los Alcatraces,” or “Island of the Pelicans,” for its large pelican colony. Later, the name was shortened to Alcatraz. When the Spanish began to build the many Southern California missions, many of the native Ohlone utilized the island as a hiding place to escape the “forced” Christianity imposed upon them.

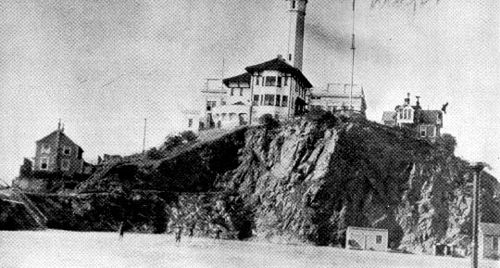

In 1848, after the end of the Mexican-American War, California, along with the island, came under the control of the United States. It wasn’t long before the U.S. Army realized the strategic position of the island as a defensive site for the San Francisco Bay and began the work of building a fortress atop the sandstone outcropping in 1853. Construction began with a temporary wharf, shops, barracks, and offices. Incorporating the land’s ruggedness into the defense plan, the laborers blasted the rock and laid brick and stone to create steep walls around the island. By 1854, the lighthouse was completed, and eleven cannons were mounted.

Fort Alcatraz (1850-1907)

Fort Alcatraz

The rest of the fortress would take years to complete, as most of the area laborers were much more interested in prospecting for gold rather than the back-breaking work of building Fort Alcatraz. Another cause of delay was the lack of quality building materials. While some sandstone was quarried on nearby Angel Island, much of the granite used in the building had to be imported from China.

The first deaths on the island occurred in 1857 when the crew was excavating a roadway between the wharf and the guardhouse. Suddenly, a 7,000 cubic-yard landslide buried several of the laborers, and two men were killed.

However, the fortress slowly took shape as roadways, additional outbuildings, and the final defensive position – the Citadel were built. Completed in 1859, the fortress included a row of enclosed gun positions to protect the dock, a fortified guardhouse to block the entrance road, and the three-story citadel atop the island that served as an armed barracks and the last line of defense. The only access to the citadel was a drawbridge over a deep dry moat surrounding the entire building. The structure was designed to hold as many as 200 soldiers with provisions that could withstand a four-month siege.

In December 1859, Captain Joseph Stewart and 86 men of Company H, Third U.S. Artillery, took command of Alcatraz Island. Fort Alcatraz soon took the lead role as the most powerful coastal defense in the West. In addition to its strategic defensive position, the island also took on serving as a stockade for enlisted men. Recognizing that the cold water (53° F) and the swift currents surrounding the island made it an ideal site for a prison, eleven of the soldiers who arrived with Captain Stewart were incarcerated in a cell block in the guardhouse basement. Just two months later, another soldier, who was said to have been insane, was jailed with the others. Before long, other forts with less secure garrisons began to send their deserters, escapees, and other prisoners to the island.

In April 1861, Alcatraz took on another role — defending the Union state of California from Confederates when the Civil War broke out. As California’s population included both Union and Confederate supporters, tensions ran high on the California coast, and the fort and its men were tasked with calming the threat of local war and protecting the City of San Francisco. Commanding the Department of the Pacific, Colonel Albert Sidney Johnston sent 10,000 muskets and 150,000 ammunition cartridges to Fort Alcatraz, and the island became the most powerful fort west of the Mississippi River. The new fortress soon deflated Confederate sympathizers’ hopes that the San Francisco Bay could be taken and California brought into the Confederacy.

“I have heard foolish talk about an attempt to seize the strongholds of government under my charge. Knowing this, I have prepared for emergencies and will defend the property of the United States with every resource at my command and with the last drop of blood in my body. Tell that to our Southern friends!”

— Colonel Albert Sidney Johnston, Commander of the Department of the Pacific, U.S. Army, 1861

Though no one ever attacked the rugged island during the Civil War, the military personnel on Alcatraz increased to over 350 men.

On August 27, 1861, Alcatraz was officially designated as the military prison for the Department of the Pacific, which covered most of the territory west of the Rocky Mountains. Like most prisons of the time, the conditions in the cell house were terrible, with men sleeping on the stone floors side-by-side. With no heat, running water, or sanitary facilities in the cells, sickness became common among the prisoners.

Approaching Alcatraz Island by Kathy Alexander.

The first Confederate threat to California occurred in March 1863 when the army learned that a group of Southern sympathizers planned to overtake San Francisco Bay. Their strategy was to arm a schooner, use it to capture a steamship, blockade the harbor, and attack the fort. However, when the schooner’s captain bragged about the scheme while drinking in a tavern, the news was quickly relayed to Union officials. On the night the schooner was set to sail, the U.S. Navy seized the ship and arrested the crew. The army found cannons, ammunition, and 15 more men hidden in the ship when the boat was towed to Alcatraz.

During the Civil War, Alcatraz’s role as a military prison increased. When the Confederates were arrested from the schooner, they joined numerous other military prisoners and local civilians who had been arrested for treason. Soon, the rooms in the guardhouse were filled, and a temporary wooden prison was built in 1863 just north of the guardhouse. Later, it was replaced with several adjoining structures called the Lower Prison. Built by jailhouse labor as part of their punishment, the prisoners also constructed additional housing on the island.

Alcatraz Citadel 1908.

As the Civil War continued, the U.S. Army devoted more resources to Alcatraz, and in 1864, the first 15-inch Rodman cannons were mounted. Additional “bombproof barracks” were also built. By the time the Civil War ended in 1865, the island had over 100 cannons. However, the only time they were used was during the official mourning salute during San Francisco’s honorary funeral procession for President Lincoln.

After the Civil War, Confederate sympathizers caught celebrating the death of President Lincoln were sent to Alcatraz along with other military convicts and various malcontents of society. It was also after the war that thousands of emigrants began to flood to the west, creating the Indian Wars of the late 1800s. At this time, Indians were often utilized by the cavalry as scouts, and those convicted of mutiny or other crimes were sent to Alcatraz, housed side by side with some of the worst murderers, rapists, and criminals in the West. Other Native Americans who thwarted the U.S. Government were also sent to the “Rock. The first Native American to be sent to Alcatraz was Paiute Tom, who was transferred from Camp McDermit in Nebraska on June 5, 1873. Two days later, he was shot and killed by a guard. The reason for the transfer and the killing has been lost in history.

Later that same year, two Modoc Indians named Barncho and Sloluck were sent to Alcatraz. Arrested for participating in the murder of members of a peace commission during the Modoc Wars of northeastern California, they had been sentenced to hang and four other Modoc Indians. Convicted at Fort Klamath, Oregon, President Ulysses S. Grant spared the two because of their youth and sent them to Alcatraz. While at Alcatraz, Barncho died of tuberculosis, but Sloluck was released in February 1878 and joined the remaining members of his tribe exiled in Indian Territory.

Other Native Americans accused of mutiny, Indian campaigns against the army, or escapees from other prisons were also sent to Alcatraz. One such prisoner, Chief Kaetena, a compatriot of Geronimo, was sent to Alcatraz after battling against General George Crook’s army. After spending two years on the rock, he was released in March 1886, at which time Crook wrote, “His stay on Alcatraz has worked a complete reformation in his character.”

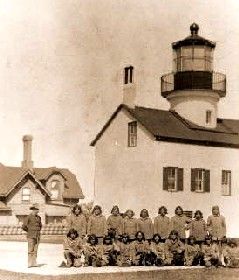

Hopi inmates at Alcatraz Island are pictured in front of the original lighthouse.

In January 1895, the largest number of American Indians were sent to Alcatraz from northern Arizona. Nineteen Hopi leaders, who had been involved in land disputes with the government and refused to comply with mandatory government education programs for their children, were severely punished by sending them to the “Rock.” A San Francisco newspaper of the time, The Call, stated the Hopi “have been rudely snatched from the bosom of their families and are prisoners . . . until they have learned to appreciate the advantage of education.” Only after the Hopi had pledged to “cease interference with the government’s plans for the civilization and education of its Indian wards” were they released.

Throughout the late 1800s, the prison complex housed an average of 100 men. During this time, the old cannons were gradually removed, and by 1891, only seven remained.

During the Spanish-American War of 1898, thousands of troops passed through San Francisco to or returned from the Philippines. Upon their return, many soldiers brought back tropical contagious diseases, and San Francisco’s hospitals filled. Many of these soldiers returned as prisoners, and Alcatraz’s hospital was also packed with men who had contracted diseases, several of which died of their illnesses. During this time, four prisoners tried to paddle their way to the mainland on a butter vat, only to be returned to the island along the strong currents.

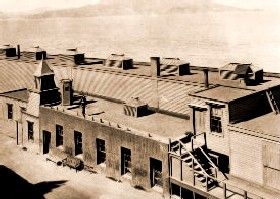

Alcatraz Lower Prison.

By the turn of the century, the prison’s population had swelled to more than 400, and another prison complex was hastily built on the parade ground.

Called the Upper Prison, it consisted of three wooden cell houses with two tiers each, surrounded by a stockade fence. Over the next several years, additional support buildings were added to the Upper Prison, and the Lower Prison was converted into workshops for prison labor.

Both the Upper and Lower Prisons were firetraps, and in 1902, an oil lantern fire almost destroyed the Lower Prison. In 1906, when the earthquake hit San Francisco, burning much of the city, officials evacuated 176 city prisoners to Alcatraz for nine days. Recognizing the fire hazards of Alcatraz, new concrete barracks were soon built by prison labor.

Alcatraz Military Prison (1907-1934)

Buildings on Alcatraz Island by Kathy Alexander.

As the U.S. military’s ships became increasingly powerful, Alcatraz’s defensive purposes became obsolete. In 1907, Alcatraz was re-designated as the “Pacific Branch, U.S. Military Prison,” and prison guards replaced infantry soldiers.

New projects soon began to accommodate the many military prisoners, and during World War I, the prison housed German prisoners of war. The upper citadel was torn down, and a huge cell house was built over the citadel basement and moat. The new cell house, completed in 1912, was the largest reinforced concrete building in the world at the time, containing four cell blocks with a total of 600 cells, each with a toilet and electricity.

In 1915, the island was renamed the “Pacific Branch, U.S. Disciplinary Barracks,” and a new emphasis was put on education and rehabilitation. Those convicted men with less serious offenses soon attended military training, remedial education, and vocational training. The plan was so successful that many soldiers were restored to active duty after serving their sentences. Prisoners with more serious offenses were not given these opportunities and were dishonorably discharged from the Army after serving their terms.

Alcatraz was a minimum-security prison. As a disciplinary barracks, it was a minimum-security prison, and most prisoners were locked in their cells only at night. During the day, they spent their time in classes or work activities. Throughout these years, several inmates tried to escape the island by boarding boats heading to the mainland, swimming, or clinging to wooden objects.

Driftwood was used for escape attempts in 1912, 1916, and 1927, and a ladder was used during an escape attempt in 1929. Most of those who attempted to escape through the water never made it to shore. Of those who tried, some were rescued and returned to the island, but others drowned.

The most successful escape was on November 28, 1918, when four prisoners escaped with rafts. The authorities assumed they had drowned in San Francisco Bay, but they later appeared in Sutro Forest. Only one of them was recaptured.

As a Military Prison, there were at least 80 men who attempted to escape in 29 separate attempts. Of those, 62 were captured and returned to the prison; one may have drowned, and the fate of 17 others was unknown.

By 1933, the army decided that the island was too expensive to operate. Its location was the biggest problem, with the high costs of importing water, food, and supplies.

At this time, the gangster era was in full swing, brought on by the desperate need of the great depression, combined with Prohibition. The nation’s cities witnessed terrible violence as shoot-outs and public slayings became frequent when mobsters took control. The ill-equipped law enforcement agencies were often bought off by the gangsters or cowered before the better-armed gangs of nattily dressed men. Simultaneously, the existing prisons were experiencing several escapes, rioting, and gang-related murders.

Alcatraz was the ideal solution to the problem, and J. Edgar Hoover jumped on the opportunity to create a “super-prison” that would instill fear in the minds of would-be criminals, offered no means of escape, and a place where inmates could be safely controlled. Negotiations soon began, and Alcatraz was transferred to the Bureau of Prisons in October 1933.

By the early part of 1934, eighty years of U.S. Army occupation ended. Except for 32 hard case prisoners, who were to remain on the island and incarcerated in the “new” prison when it was completed, the others were transferred to Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, and Fort Jay, New Jersey.

Alcatraz Island Federal Penitentiary (1934 -1963)

Cellblock at Alcatraz by Kathy Alexander.

Beginning on January 1, 1934, much to the chagrin of the people of San Francisco, the Bureau of Prisons began the process of selecting a warden and upgrading Alcatraz to an “escape-proof” maximum security prison. Four guard towers were constructed at strategic points around the island, and 336 of the cells were reconstructed with tool-proof steel cell fronts and locking devices operated from control boxes. None of the cells adjoined a perimeter wall.

Every window in the prison building was also equipped with tool-proof steel window guards, and two gun galleries were erected in the cellblock that allowed guards armed with machine guns to oversee all inmate activities.

The mess hall and main entrance were equipped with built-in tear gas canisters in the ceiling that could be remotely activated from both the gun gallery and the outside observation points.

New technology allowed electromagnetic metal detectors to be utilized, positioned outside the mess hall and at the workshop entrances. Electricity and sanitary facilities were upgraded in each cell, and all of the utility tunnels were cemented so that no prisoner could enter or hide in them.

In addition, the barracks buildings were altered to provide comfortable quarters for the prison guards and their families. The living facilities included four wood-frame houses, one duplex, and three apartment buildings. A large house adjacent to the cell house was designated for the warden, while the duplex was assigned to the Captain and Associate Warden.

The collaborative effort of U.S. Attorney General Homer Cummings and Director of the Bureau of Prisons Sanford Bates produced a legendary prison that seemed both necessary and appropriate to the times. It was so forbidding that it was eventually nicknamed “Uncle Sam’s Devil’s Island.”

Appointed as the first warden, James A. Johnston came with over 12 years of experience in the California Department of Corrections at San Quentin and Folsom Prisons. Johnston had already developed a reputation for strict ideals and a humanistic approach to reform. However, he was also known to be a strict disciplinarian, and his rules of conduct were among the most rigid in the California correctional system.

Believing in a system of rewards and consequences, Johnston and Federal Prisons Director Sanford Bates established the guiding principles under which the prison would operate. He and his hand-picked correctional officers then enforced the guidelines by rewarding inmates with privileges or sentence reductions for hard work and harshly punishing inmates who defied prison regulations.

One of the regulations that were enacted for the prison was that no prisoner would be directly sentenced to Alcatraz from the courts. Instead, they “earned” their transfer to the island from other prisons by attempting to escape, exhibiting unmanageable behavior, or those that had been receiving special privileges. Therefore, Alcatraz became home to the “worst of the worst” criminal elements in the nation.

On July 1, 1934, the maximum security, minimum-privilege penitentiary officially received its first prisoners. The 32 hard-case prisoners who had been “left” by the Army were turned over to Alcatraz authorities, the first of which was a man named Frank Bolt, who was serving a five-year sentence for sodomy.

Al Capone.

Other inmates in this first group of men had committed such crimes as robbery, assault, rape, and desertion. The next month, 69 more prisoners arrived from the McNeil Island and Atlanta Penitentiaries, the most famous of which, inmate #85, was Al Capone.

Warden Johnston began a custom of meeting the new inmates upon their arrival to Alcatraz. When Capone arrived, Johnston immediately recognized the grinning man quietly making smug comments to nearby inmates. When Capone’s turn to approach the warden, he attempted to flaunt the power he had enjoyed at the federal pen in Atlanta by asking questions of the warden on the inmate’s behalf.

While in Atlanta, he successfully bribed the guards for additional favors such as unlimited visiting privileges, liquor, and uncensored reading materials.

He was so successful in gaining special privileges that family members took up residence at a nearby hotel, through which he continued to run his organization in Chicago.

However, Johnston was not to be manipulated and immediately assigned him his prison number and ordered him back in line with the others.

Capone’s arrival at Alcatraz generated more newspaper headlines than the opening of the prison itself, beginning an era of public fascination with the maximum-security prison.

Overlooking the Recreation Yard, by Kathy Alexander.

During Capone’s sentence on the “Rock,” he would make several other attempts to con Johnston into allowing him special privileges, but all would be denied. Capone spent 4 ½ years at the “Rock,” holding various menial jobs at the prison. While he was there, he spent eight days in isolation due to a fight with another inmate and was stabbed with a pair of scissors by another prisoner.

Eventually, he began to suffer symptoms of syphilis that he had contracted years earlier and actually spent more time in the hospital than he did in the cell house. In 1938, he was transferred to Terminal Island Prison in Southern California to serve out the remainder of his sentence. He was released in November of 1939, settled in Miami, and died in 1947 at the age of 48.

Arriving on the second “official” shipment to Alcatraz in September was George “Machine Gun” Kelly. First involved in bootlegging, he was sentenced to Leavenworth, where he spent three years. Obviously not rehabilitated, he resumed a life of crime, this time robbing banks. He soon advanced to kidnapping, and in 1933, he held for ransom a wealthy Oklahoma oil magnate. After his capture, he was given a life sentence and returned to Leavenworth. However, within months, he was transferred to Alcatraz, where he was said to have been a model prisoner for the next seventeen years. When Kelly suffered a mild heart attack, he was returned to Leavenworth in 1951 and was paroled in 1954. Within months, he suffered another heart attack and died at the age of 59.

As part of its maximum-security efforts, the ratio of guards to prisoners was one to three, compared to other prisons, where the ratio averaged one to twelve. Also, inmates were allowed no visitors for the first three months and, afterward, only one visitor per month, a privilege that had to be earned. While prisoners were allowed limited access to the prison library, no newspapers, unapproved books, or radios were allowed. All incoming and outgoing mail was screened, censored, and retyped. Consideration for work assignments was based on a prisoner’s conduct record. Each prisoner was assigned a private cell with only the basic minimum necessities such as food, water, and clothing.

A cell in Alcatraz, by Kathy Alexander.

The routine was the same every day. Prisoners were awakened at 6:30 a.m., given time to tidy their cells and wash up, and then marched silently to the mess hall. Following breakfast, the prisoners were given their work assignments for the day, and after dinner, they were again locked within their cells. The strict rules required inmate counts every half hour.

However, the worst rule was Warden Johnston’s strictly enforced silence policy. Many of the inmates considered this to be their most unbearable punishment. Prisoners were only allowed to talk during meals, in the yard on Saturdays, and for three minutes during morning and afternoon work breaks. Though the silence policy was later relaxed, several reports reported that inmates were driven insane by the severe rule of silence.

Many stories, including the classic movie “_Escape From Alcatraz,_” tell of an inmate by the name of Rufe Persful, a former gangster and bank robber, who went so far as to take a hatchet and chop off the fingers of one of his hands while working in one of the shops. Though the strict rule, no doubt, did drive men insane, Persful actually lost his fingers when a shop door blew shut on his hand.

The routine was unyielding, day after day, year after year. As quickly as privileges were earned, they could be revoked for the slightest infraction of the rules.

The only “redeeming” qualities of the prison were the private cells, and the food quality served there. These, too, had their reasons. The first was to isolate these hardened criminals, while the second was to prevent riots that were often known to start in other prisons because of the poor quality of food.

Arthur R. Doc Barker.

Though the vast majority of Alcatraz prisoners were never seen on a wanted poster, other notorious criminals held at the prison over the years included two members of the Ma Barker Gang – Arthur “Doc” Barker, the last surviving son, and Alvin “Creepy” Karpis, who was in a partnership with Ma Barker.

Other notorious criminals included Robert “Birdman of Alcatraz” Stroud and Floyd Hamilton, a gang member and driver for Bonnie and Clyde.

While Ma Barker’s gang of hoodlums, Doc Barker and Alvin “Creepy” Karpis, terrorized the Midwest between 1931 and 1936. Their many crimes included murder, bank robbery, kidnapping, and a train robbery. Karpis’ flamboyant style had earned him the wrath of J. Edgar Hoover, and he soon found himself with the infamous distinction of being “Public Enemy No. 1.”

Doc Barker was arrested in January 1935 and later sent to Alcatraz from Leavenworth. He was killed in an escape attempt from Alcatraz in 1939. Carpis, who was arrested in New Orleans in May 1936, found himself in Alcatraz just a few months later. He spent the next 26 years on the “Rock” before being transferred to McNeil Island in April 1962. In 1969, he was released and deported to his homeland of Canada. Carpis died in 1979.

Robert Stroud, the Birdman Of Alcatraz.

Robert Stroud, known as the Birdman of Alcatraz, received very little notoriety until he gained attention in the 1962 movie “The Birdman of Alcatraz.” Stroud, who was convicted of manslaughter in 1909, was initially sent to McNeil Island to serve a 12-year sentence. While there, he was difficult to manage, and after attacking an orderly, he was sent to Leavenworth. After less than four years at the Kansas prison, he killed a guard and was later sentenced to hang. After his mother appealed to President Wilson, the sentence was commuted to life. It was during Stroud’s thirty years as a prisoner at Leavenworth that he began to study birds, which gained him international attention. When Stroud began to openly violate prison rules to continue his birding experiments and communications with bird breeders, he was sent to Alcatraz in 1942, where he never again was permitted to continue his avian studies.

The “Birdman” occupied a cell in D Block for approximately six years before he was moved to the prison hospital in 1948 to segregate him from the rest of the population. After he genuinely became ill, he was transferred to a Federal Medical Facility in Springfield, Missouri, in 1959. Four years later, Stroud died of natural causes.

Though the prison was heavily fortified, and it was assumed that the “treacherous waters” of the San Francisco Bay would prevent any escape, several attempts were made throughout the years.

From a total of 1,545 prisoners that spent time at the federal prison, 36 men attempted to escape in fourteen 14 separate attempts. Of those, 20 were captured, seven were shot and killed, two drowned, and five were never found, assumed by prison authorities to have drowned.

Theodore Cole and Ralph Roe were the first to disappear from Alcatraz on December 16, 1937. While working in one of the workshops, Cole and Roe had, over a period of time, filed their way through the flat iron bars on a window. After climbing through the window, they went to the water’s edge and disappeared into San Francisco Bay. Prison authorities declared them to have drowned, but four years later, a San Francisco Chronicle reporter reported the men were alive and well in South America.

Scars from the “Battle of Alcatraz” can still be seen on the floor, by Kathy Alexander.

The bloodiest escape attempt occurred over a three day period on May 2-4, 1946. In this incident, known as the “Battle of Alcatraz,” six men by the names of Bernard Coy, Joseph Cretzer, Sam Shockley, Clarence Carnes, Marvin Hubbard, and Miran Thompson took control of the cell house. Overpowering officers and gaining access to weapons and keys, they planned to escape through the recreation yard door. However, when they found they didn’t have the key to the outside door, they decided to fight rather than giving up. During the next couple of days, the prisoners killed two of the guards they had taken hostage. Eventually, Shockley, Thompson, and Carnes returned to their cells, but Coy, Cretzer, and Hubbard continued to fight.

The U.S. Marines were eventually called out to assist, and the escape attempt ended. In the melee, Coy, Cretzer, and Hubbard were killed, and 17 guards and one prisoner were wounded. Shockley, Thompson, and Carnes later stood trial for the officers’ death; Shockley and Thompson received the death penalty and were executed in the gas chamber at San Quentin in December 1948. Carnes, just 19 years old at the time, received a second life sentence.

On July 11, 1962, Clarence Anglin, his brother John, and Frank Morris also disappeared from Alcatraz. Their escape was made famous by Clint Eastwood’s movie, “Escape From Alcatraz.”

One of the heads used in the escape of the Anglin brothers and Frank Morris is still on display in a cell by Kathy Alexander.

The three escapees, along with another man named Alan (Clayton) West, made plaster heads with real hair swept from the barbershop floor. On the night of the escape, they left the heads on their beds and crept through the ventilators in their cells, which had been widened with stolen spoons from the kitchen, into the utility corridor. West could not fit through his hole and remained behind. From there, they went to the roof, then down to the water’s edge. Though prison authorities believed the men had drowned, no bodies were ever recovered.

During the last escape from Alcatraz on December 12, 1962, John Paul Scott, 35, swam from the island to Fort Point under the southern part of the Golden Gate Bridge, proving that it could be done. Along with another prisoner named Darl Parker, the pair bent the bars of a kitchen window in the cell house basement and escaped.

Parker was discovered on a small outcropping of rock a short distance from the island. However, Scott, a better swimmer, made it to Fort Point beneath the Golden Gate Bridge. Collapsing from exhaustion and hypothermia, he was soon found by two teenage boys who called for help. He was then taken to the military hospital at the Presidio Army base. After being treated for shock and hypothermia, he was returned to Alcatraz.

The old Officers’ Club was burned out during the Indian occupation of the island by Kathy Alexander.

Primarily due to rising costs, its isolated location, and deteriorating facilities, Alcatraz was the most expensive of any state or federal institution. Simultaneously, the prison operating philosophy was changing to reinstitution and rehabilitation rather than the wholesale warehousing of inmates. The government soon began to build a new prison in Marion, Illinois, with plans to shut down Alcatraz. Though it was said that J. Edgar Hoover opposed closing Alcatraz, his power base had eroded over the years, and his opinion was ignored.

Attorney General Robert Kennedy officially closed the doors of Alcatraz on March 21, 1963, when the final 27 inmates were taken off the island.

It was the first time that reporters were ever allowed on the “Rock” to cover its closing, which made headlines across the country. Afterward, Alcatraz Island was transferred to the General Services Administration in May of 1963.

During its 29 years of operation as a federal prison, the fog-enshrouded island confined more than 1,500 men under intolerable rules and deprivation. Former prisoners continue to tell tales of the “inside,” with numerous scenes that were seemingly so terrible that many prisoners preferred death to continued incarceration.

Just as Warden Johnston had envisioned it, life was hell for the prisoners on the island, and in no time, it was dubbed “Hellcatraz.” Suicides and murders were common under the severe and stark rule system of the prison. Infractions of the rules would quickly land a prisoner in the “D” block, known as the “treatment unit.” Here, men could leave their four-by-eight cells only once in seven days for a brief, ten-minute shower. Harsher punishments included solitary confinement, in total darkness, for days without any release or confinement in the dreaded steel boxes.

As prisoners looked out the barred windows of the prison, they saw party barges passing by, cars traveling on the highways of the mainland, and life going on normally for those not encased upon the Rock. One prisoner described it this way: “I looked out the window once when I first came to Alcatraz and saw that, and I vowed to never look out the window again for as long as I was there.”

Though one of America’s most escape-proof prisons, Alcatraz served as an experiment that would never again be repeated. Segregation on this scale had never before been seen and would never again be practiced.

During the years that the island was occupied by the prison, eight prisoners were murdered by other inmates, five committed suicide, 15 died from illness, and numerous others went insane.

From 1963 to 1969, the island remained abandoned, except for a short Native American occupation in 1964. Lasting only four hours, the symbolic occupation was led by Richard McKenzie and four other Sioux Indians, who demanded the use of the island for a Native American Cultural Center and Indian University.

Though viewed as insignificant at the time, these sentiments would later resurface. In the meantime, several other parties lobbied for various development ideas, ranging from a West Coast version of the Statue of Liberty to shopping centers and resort complexes. In 1969, Alcatraz Island again made national news when another group of Native Americans claimed the island as Indian land.

Native American Occupation (1969-1971)

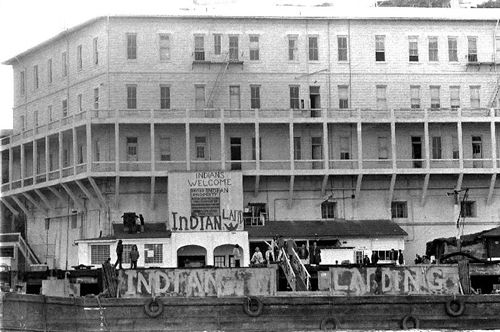

The dock at Alcatraz welcomes Native Americans after it was occupied. Photo by Michelle Vignes, courtesy of California State University.

On November 9, 1969, Richard Oakes, a Mohawk Indian, and a group of supporters set out on a chartered boat to symbolically claim Alcatraz Island for the Native Americans. The occupation demands were almost identical to those made in 1964 by the Sioux who had claimed the island.

Just a little more than ten days later, on November 20th, the symbolic occupation turned into a full-scale occupation that would last for the next 19 months.

The initial occupation, planned by Richard Oakes, included a group of Indian students, as well as urban Indians from the Bay Area. Since so many different tribes were represented by the Native Americans, the name “Indians of All Tribes” was adopted for the group.

The federal government initially insisted that the Indians leave the island and placed an ineffective barricade around it. However, the government eventually agreed to hear their demands, and the group realized that prolonged occupation was possible. Oakes soon recruited eighty more Indian students from UCLA, and the group of occupants reached some 100 Native Americans.

In no time, the occupants began to organize, with Chief Oaks as the unofficial mayor of Alcatraz. They elected a council and provided for security, sanitation, daycare, school, and housing. Their negotiations demanded the deed to the island and the establishment of an Indian University, cultural center, and museum.

There are still signs of the Native American occupation at Alcatraz today, by Kathy Alexander.

Though initially, government negotiators insisted that the occupiers could have none of these and insisted that the Indians leave the island, the government soon adopted a position of non-interference. This position was taken largely due to the strong public support of the Native Americans and their demands. Advocates from show business celebrities to the Hell’s Angels supported the Indian occupation, and federal officials began to meet with the Native Americans.

Often sitting cross-legged on blankets inside the old mess hall, the Indians and officials discussed the social needs of the Native Americans.

While it appeared to the Indian occupants that their demand might actually be met, the government was, in fact, playing a waiting game, hoping that public support would wane. The Indians would voluntarily end the occupation.

At one point, the government offered a portion of Fort Miley in San Francisco as an alternative site to Alcatraz. But by this time, the Indians were too dedicated to their cause to refuse any alternatives.

Less than two months after the initial occupation, the Indian group began to fall into disarray, with two groups rising in opposition to Richard Oakes. In the meantime, many of the Indian students returned to school in January 1970. Gradually, the students were replaced by other Indians who were not involved in the initial occupation.

Alcatraz Indian Occupation, photo by Ilka Hartman, courtesy California State University.

During this time, many non-Indians also began to take up residence on the island, including the homeless and many from the San Francisco hippie and drug culture.

Organization virtually fell apart when Richard Oake’s 13-year-old stepdaughter fell three floors down a stairwell to her death. Following her death, Oakes left the island, leaving it without a strong leader. The two competing groups then began to maneuver back and forth for leadership.

The Indians also faced the same problems that had hindered the military and prison administrations—the lack of natural resources and the requirement that all supplies, food, and water be ferried by boat. The process was not only exhausting but also extremely expensive.

Despite the prohibition of drugs and alcohol by the Indians, the contraband soon began to be brought onto the island by the many non-Native Americans who had also encamped upon Alcatraz. Without strong leadership, the situation quickly became unmanageable, and the organization of the community fell apart. Daily reports from the government caretaker on the island, as well as complaints from the remaining occupants, described the open use of drugs, destruction of property, including graffiti and vandalism, and the general disarray of leadership.

Without the equalitarian form of government that was supposed to prevail, there was no one with whom the government could negotiate.

In response, the government, in an attempt to evacuate the island, shut off all electrical power and removed the water barge, which provided fresh water for those occupying the island. Three days after removing the water barge, on June 1, 1970, a fire was accidentally started and raged through several of the buildings. When the blaze finally died out, the Warden’s home, the lighthouse keeper’s residence, and the Officers’ Club were burned to the ground. Also severely damaged was the historic lighthouse built in 1854.

Fire during the Occupation of Alcatraz.

The Native Americans were soon forced to resort to drastic measures to survive and began to strip copper wiring and tubing from the buildings to sell as scrap metal. Three of the occupiers were arrested and found guilty of selling some 600 pounds of copper. This story, along with other news of the events taking place on the island, began to be told in the press. Before long, little support could be found for the Indians’ occupation.

When two oil tankers collided in the San Francisco Bay in January 1971, the federal government stepped in. Though no blame was held against the island’s occupiers, a removal plan began to be developed. Designed to take place with as little force as possible and at a time when the smallest number of people were on the island, the forced removal took place on June 10, 1971.

On that date, the occupation ended when 20 armed federal marshals, assisted by the Coast Guard, swarmed the island, removing five women, four children, and six unarmed Indian men.

Though the specific demands for the island itself were not realized, the initial underlying goal of the first occupants was to awaken the American public to the reality of the Native American plight. As a result, the official government policy of terminating Indian tribes was ended, and a new policy of Indian self-determination was recognized.

The occupation also resulted in the return of Blue Lake and some 48,000 acres of land to the Taos Indians, a Native American University near Davis, California, and the hiring of Native Americans to the Bureau of Indian Affairs offices in Washington, D.C.

The occupation was the longest of any federal facility by Native Americans to this day.

Golden Gate National Recreation Area

Fort Point and Golden Gate today, by Jon Sullivan.

On October 12, 1972, Congress created the Golden Gate National Recreation Area, and the island became part of the National Park Service. After some slight modifications to the facility to make it safe for the public and the razing of the guards’ residences that were deteriorated beyond repair, the park opened in the fall of 1973. Since that time, it has become one of the most popular of the Park Service sites, with more than a million visitors every year.

Along with its rich history and the prison itself, visitors also marvel at the wildlife, expansive gardens, and dramatic views of the Golden Gate Bridge, downtown San Francisco, the Bay Bridge, and Treasure Island.

As one looks east towards San Francisco Bay, it is easy to imagine the island as the location of a luxurious resort. But as visitors continue their tour, the reality of the cell house, solitary confinement cells, and the pitch-black “hole” quickly bring back the reality of the Island and its past.

The “thrill” of Alcatraz has been portrayed in several Hollywood movies over the years, such as 1962’s “Birdman of Alcatraz,” Clint Eastwood’s popular 1979 film “Escape from Alcatraz, “_Murder in the First_” in 1995, and “_The Rock_” in 1996. Though none of these movies are completely accurate in their historical details, they have provided a glimpse at prison life upon the “Rock.”

Many former inmates of the prison who are still alive today find it extremely hard to grasp the idea of why so many people would want to visit a place that represented to them only anguish and despair. To them, the term “recreation area” is an oxymoron in the extreme.

Alcatraz Administration Building, by Kathy Alexander.

But we do visit, so much so that if you are planning a trip to the island, reservations are recommended days in advance as the tours fill up fast. The tour provides a brief orientation from a park ranger, a ranger-led or self-guided tour, and an orientation film. An audio tour is also available for a couple of extra dollars, which is well worth it, as guards and former prisoners share their experiences of the prison.

Today, the military base barracks, prison cell house, the oldest lighthouse on the West Coast, and several other buildings remain.

But the Golden Gate National Recreation Area is much more than Alcatraz Island; it is also one of the largest urban parks in the world, with an acreage of two and ½ half times the size of San Francisco County.

Not one situated in one continuous location, the numerous sites of the park that contains 739 historic structures, including five National Historic Landmarks and 12 National Register Properties, stretch from northern San Mateo County to southern Marin County and include several areas of San Francisco. Encompassing 69 miles of bay and ocean shoreline, the park features military fortifications that span centuries of California history, various cultural landscapes, numerous archeological sites, and the homeland of the Coastal Miwok and Ohlone people. It displays collections of more than 3 million historic objects, documents, images, and specimens.

Point Bonita Lighthouse, by Dave Alexander.

North of the Golden Gate Bridge in Marin County, the park includes Bolinas Ridge, Forts Baker, Barry, and Cronkhite; Gerbode Valley, Kirby Cove, Marin Headlands, Muir Woods National Monument, Beach, and Overlook; the Nike Missile Site, Olema Valley, Point Bonita Lighthouse, Stinson Beach, and Tennessee Valley.

South of the Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco County are the sites of Alcatraz Island, Baker Beach, Battery Chamberlin, China Beach, the Cliff House & Sutro Baths, Crissy Airfield, Beach and Field Center; Forts Funston, Mason, and Point; Lands End, Ocean Beach, the Pacific West Regional Information Center, Sutro Historic District, and the Presidio of San Francisco. South of San Francisco, in San Mateo County, the park includes Milagra Ridge, Mori Point, the Phleger Estate, and Sweeney Ridge.

Contact Information:

Alcatraz Island National Park Service

Golden Gate National Recreation Area

Fort Mason, Building 201

San Francisco, California 94123

Visitor Information – 415-561-4900

Reservations – 415-705-5555

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated July 2024.

See our Alcatraz Photo Gallery HERE

Also See:

Fort Baker – Protecting the California Coast

Fort Point – Standing Guard at the Golden Gate