Harlots of the Barbary Coast – Legends of America (original) (raw)

By Herbert Asbury

One of the many “ladies of the line.”

There was such a dearth of females in the San Francisco of gold-rush days that a woman was almost as rare a sight as an elephant, while a child was an even more unusual spectacle. It is doubtful if the so-called fair sex ever before or since received such adulation and homage anywhere in the United States; even prostitutes, ordinarily scorned and ostracized by their honest and respectable customers, were treated with exaggerated deference. Men stood for hours watching the few children at play; and whenever a woman appeared on the street, business was practically suspended. She was followed through the town by an adoring crowd, while self-appointed committees marched ahead to clear the way and to protect her from the too boisterous salutations of the emotional miners.

Once while an important auction of city lots was in progress in a Montgomery Street building, a man poked his head into the auction room and shouted: “Two ladies going by on the sidewalk!” The entire crowd immediately abandoned the auction and rushed into the street to watch the women pass. It is related that they bared their heads in reverence, but that part of the story is probably the added touch of the incorrigible romancer.

According to one historian, there were only 15 white women in San Francisco in the spring of 1849, but his estimate may be doubted, for San Franciscans were inclined to regard as white-only natives of the United States and of a few European countries. In any event, however, the female population probably did not exceed three hundred for at least a year after the beginning of the gold excitement. Of this number, perhaps two-thirds were harlots from Mexico, Peru, and Chile. Together with male natives of these and other Central and South American countries, they were known in San Francisco by the generic name of Chilenos, or, contemptuously, “greasers.”

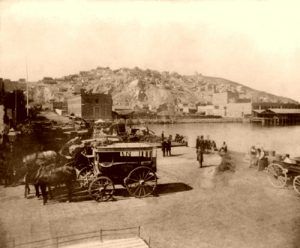

These pioneer prostitutes occupied tents and board shanties in the vicinity of Clark’s Point, about where Broadway and Pacific Street run into the Bay, and on the eastern and southern slopes of Telegraph Hill, a 300-foot elevation west and north of Yerba Buena Cove, from the summit of which the arrival of ships off the Golden Gate was signaled to the town in the valley and along the beach. Sometimes as many as half a dozen Chileno women used the same rude shelter, receiving their visitors singly or en suite, with no regard whatever for privacy, and no furniture excepting a wash-bowl and a few dilapidated cots or straw pallets. A few made a pretense of operating wash-houses, but there were scarcely any who did not devote the nights to bawdy carousal and to sexual excesses and exhibitions. And the days, also, if there was an opportunity.

Many of the men who had brought them to California had gone on to the gold-fields, but others had remained in San Francisco, where they dwelt promiscuously with the harlots. They lived off the earnings of the women and what they could steal from the men who frequented the district. They also operated a few small, crooked gambling houses.

During the first six months of 1850, approximately 2000 women, most of whom were harlots also, arrived in San Francisco from France and other European countries and from the Eastern and Southern cities of the United States, principally New York and New Orleans, Louisiana. Thereafter they came on every ship, and within a few years, San Francisco possessed a red-light district that was larger than those of many cities several times its size.

In October 1850 the Pacific News announced that 900 more women of the French demi-monde, carefully chosen from the bagnios of Paris and Marseilles for their beauty, amiability, and skill, were expected, and in the same issue delicately informed its readers that in the mines Indian women were available “at reasonable prices.” Unfortunately, only fifty of the French women arrived, but that was a sufficient number to cause a considerable commotion among the miners, who were naturally eager to determine for themselves if the ladies were as adept in the practice of their profession as was popularly supposed.

Most of these accomplished courtesans were attended by their pimps, whom they called macquereaux, a designation which the forthright San Franciscans soon shortened to “macks.” These unsavory gentries are still so-called in San Francisco, although the red-light district was officially abolished some 20 years ago, and the city now, of course, has no prostitutes.

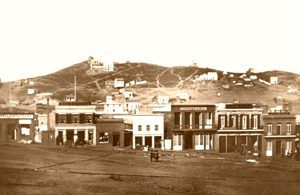

Portsmouth Square, San Francisco, California

The lowest of the newly arrived harlots joined their sisters in sin in the shabby dives on Telegraph Hill and along the waterfront, but others opened or became inmates of, elaborate establishments around Portsmouth Square. By close and diligent attention to business, many of these women amassed fortunes; one popular French courtesan is said to have banked fifty thousand dollars clear profit during her first year of professional activity in the New World. Several married prominent men and themselves became ladies of consequence, successfully persuading the dead past to bury its dead. Because of the lack of virtuous women, the prostitutes, especially those who dwelt in the elegant bagnios on Portsmouth Square, took an active part in the social life of early San Francisco. They were in particular much sought after as partners at the fancy-dress and masquerade balls with which the frolicsome miner sought to divert himself.

There, according to an early historian, “the most extraordinary scenes were exhibited, as might have been expected when the actors and dancers were chiefly hot-headed young men, flush of money and half frantic with excitement, and lewd girls, freed from the necessity of all moral restraint.”

These functions were usually held in one of the large gambling houses, the gaming tables being temporarily moved to one side to make room for the festivities, although play never ceased. They were announced to the public by notices in the newspapers, and by placards posted in the streets and public houses, all bearing in large letters the warning: “NO WEAPONS ADMITTED.”

Several men were stationed at the door, and as each prospective merry-maker entered, he was required to surrender, for the duration of the festivities, his knife, revolver, or pistol, for which he received a check.

If anyone protested that he carried no weapon, the statement was considered so preposterous that he was promptly searched. Almost invariably a knife or a firearm was found secreted in some unusual part of his clothing. Music for the dancing was furnished by the regular gambling-house orchestra, but on the program of entertainment, there was always a soloist who sang at least once, to the air of O Susannah! the miners’ favorite song:

I came from Quakerdelphia,

With my washbowl on my knee;

I’m going to California,

The gold dust for to see.

It rained all night the day I left,

The weather it was dry;

The sun so hot I froze to death,

Oh, Anna, don’t you cry.

Oh, Ann Eliza!

Don’t you cry for me.

I’m going to California

With my washbowl on my knee.

I soon shall be in Frisco,

And then I’ll look around;

And when I see the gold lumps there

I’ll pick them off the ground.

I’ll scrape the mountains clean, old girl;

I’ll drain the rivers dry;

A pocketful of rocks bring back,

So, Anna, don’t you cry.

Sometimes the mistresses of the large harlotry establishments presided at elaborate social affairs to which they invited the most important men of the town. They cannily succeeded in combining pleasure with profit by introducing new girls to their guests, by presenting old favorites in new exhibitions, and by charging outrageous prices for liquor served during the function. Occasionally, however, these gatherings were almost painfully respectable. One such is thus described in The Annals of San Francisco:

Soiled Dove

“See yonder house. Its curtains are of the purest white lace embroidered, and crimson damask. Go in. All the fixtures are of a keeping, most expensive, most voluptuous, most gorgeous. . . .It is a soirée night. The ‘lady‘ of the establishment has sent most polite invitations, got up on the finest and most beautifully embossed note paper, to all the principal gentlemen of the city, including collector of the port, mayor, aldermen, judges of the county, and members of the legislature. A splendid band of music is in attendance.

Away over the Turkey or Brussels carpet whirls the politician with some sparkling beauty, as fair as frail; and the judge joins in and enjoys the dance in company with the beautiful but lost beings, whom tomorrow, he may send to the house of correction. Everything is conducted with the utmost propriety. Not an unbecoming word is heard, not an objectionable action seen. The girls are on their good behavior and are proud once more to move and act and appear as ladies.

Did you not know, you would not suspect that you were in one of those dreadful places so vividly described by Solomon. . . .But the dance is over; now for the supper table. Everything within the bounds of the market and the skill of the cook and confectioner is before you. Opposite and by your side, that which nor cook nor confectioner’s skill have made what they are—cheeks where the ravages of dissipation have been skillfully hidden, and eyes with pristine brilliancy undimmed, or even heightened by the spirit of the recent champagne. And here the illusion fades. The champagne alone is paid for. The soirée has cost the mistress one thousand dollars, and at the supper and during the night she sells twelve dozen of champagne at ten dollars a bottle! . . .No loafers present, but the male ton; vice hides itself for the occasion, and staid dignity bends from its position to twine a few flowers of social pleasure around the heads and hearts of these poor outcasts of society.”

Many of the harlot’s “cribs” were located on Telegraph Hill, Lawrence & Houseworth, 1866.

Herbert Asbury, 1933. Compiled and edited by Kathy Weiser/Legends of America, updated July 2020.

About the Author: The Harlots of the Barbary Coast was excerpted from Herbert Asbury’s, The Barbary Coast: An Informal History of the San Francisco Underworld, published in 1933. However, the text, as it appears here, is not verbatim, as it has been edited. Asbury was an American journalist and writer who is best known for his true-crime books detailing crime during the 19th and early 20th century, the most famous of which was The Gangs of New York. In earlier decades, Asbury was known for his self-described “informal histories,” which included descriptions of various cities, focusing on violence, crime, prostitution, and lurid events.

Also See: