Death Valley Ghost Towns & Mining Camps in California – Legends of America (original) (raw)

Back to the index of Death Valley Ghost Towns & Mines

20-mule team Death Valley, 1890.

Amargosa Borax Works – Located on the west side of Death Valley, Amargosa Borax Works was a smaller version of the Harmony Borax Works, which kept the borax production going year-round. The summer months were too hot to process the borax at the Harmony Borax Works, so the operations and workforce were moved to this site for several months a year. During its four years of operation, 20-mule teams were used to transport borax to the railroad. It closed in 1888, and all that’s left today are two tiny adobe walls, pieces of the mill foundation, and a sign. It is located about five miles south of Shoshone on State Road 127. The highway runs right through what was once the mill complex, and remnants are on both sides of the road.

Arrastre Spring – Situated within the Gold Hill Mining District, this site is better known today for its historic petroglyphs than for its mining activity. More…

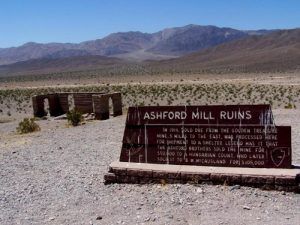

Ashford Mill Ruins, Death Valley, California.

Ashford Mine and Mill – Also called the Golden Treasure Mine, this gold mining operation was founded in 1907. Never a big producer, it is located in southern Death Valley and requires a 1.25-mile challenging hike up a 1,100-foot canyon to reach the mine. However, for the hiking enthusiast, there are several standing buildings, an ore chute, other mining remains, and a spectacular view of Death Valley. The ruins of the Ashford Mill are 3,500 feet below the floor of Death Valley. More…

Ballarat – A virtual ghost town today, Ballarat was founded in 1896 as a supply point for the mines of the Panamint Range. The primary mine supporting the town was the Radcliffe in Pleasant Canyon, just east of town. Between 1898 and 1903, the Radcliff produced 15,000 tons of gold ore. Today, this lonely ghost town still sports a couple of full-time residents. Some crumbling walls and several foundations can still be seen, as well as several old miners’ cabins and other tumbling shacks. More…

Barker Ranch before the fire in May 2009.

Barker Ranch – Famous for being the hideout of Charles Manson and his followers, it is located in a rock and boulder-filled valley in the Panamint Range. In October 1969, the Inyo County Sheriff’s Department, California Highway Patrol, and National Park Service law enforcement were searching for persons responsible for vandalism within Death Valley National Park when they stumbled upon the group hiding out at the cabin. Manson was caught hiding under the bathroom vanity. Arresting them, they were not immediately aware of who they had captured. A fire destroyed most of the main structure in May 2009, leaving only the cement and rock portions of the cabin still standing. A small one-room guest house is on the side of the main house. Twenty miles from the nearest paved road, a four-wheel drive is recommended to access the sandy, rugged roads.

Bend City – One of the first townsites on the east side of the Sierra Nevada range, the area was first settled by a few families taking advantage of the fertile Owens Valley. Before long, prospectors also climbed the hills, and in April 1860, the Russ Mining District was formed. Bend City was established on a large bend in the Owens River. It was the site of the first bridge spanning the Owens River. Never having a very large population, the settlement was destroyed by the 1872 Lone Pine earthquake, which also changed the course of the river away from the townsite. Today, there are no remains of the town located near present-day Kearsarge.

Beveridge – A small mining camp on the east side of the Inyo Mountain Range, mining occurred in the isolated Beveridge Canyon from the 1860s through the 1930s. Amazingly, the extremely remote site had a post office from 1881 to 1882. At an elevation of more than 5,500 feet, the camp was very remote and required a backpacking trip to access it. Today, there are the remains of various small pieces of mining equipment, several small mining operations, and the partial remains of several rock structures. Access to the site is on the Beverage Canyon Trail and is recommended only for experienced hikers.

Cartago – Not a complete ghost town, Cartago, located on the west side of Owens Lake about three miles northwest of Olancha, still supports about 100 people. Formerly called Carthage, Daniersburg, and Lakeville, the first post office opened in 1918. During the mining days of the 1870s, Cartago was a steamboat port for the shipment of wood and ore. After bullion bars from Cerro Gordo were hauled across Owens Lake on the steamer Bessie Brado to the Cartago boat landing, Remi Nadeau’s 14-mule teams hauled the gold to Los Angeles before returning with freight.

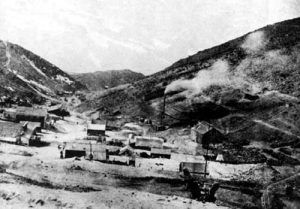

Cerro Gordo, California, in its heydays.

**Cerro Gordo, California**– Located in the Inyo Mountains of California, the Cerro Gordo Mines produced high-grade silver, lead, and zinc from 1866 until 1957. The mountain’s production led to the creation of the towns of Swansea and Keeler and the transportation hubs below.

Chrysopolis – Located on the east bank of the Owens River south of Aberdeen, the settlement was founded in 1863. Along with Black Rock, San Carlos, and Bend City, it was one of the earliest towns in the area. The name is Greek for “City of Gold.” The town flourished briefly on the arid side of Owens Valley, and a post office operated from 1866-67. Nestled among the footwall of the imposing Inyo Range, it was soon abandoned due to isolation and constant Indian troubles, which continued until Fort Independence was established. However, several settlements had sprung up on the more fertile and pleasant western side of the Owens Valley. Mining continued in the area, but the town of Chrysopolis was dead.

However, a prospecting and mining craze swept the entire region at the turn of the century, and interest revived in the old Chrysopolis mining district.

By 1910, however, the district was mostly quiet again, though miners had continued to work the area on a small basis for years. Today, the remains include mostly loose stone walls and mine tunnels. A mill site can be found on the west side of the Owens River but is inaccessible by road. The old townsite is located about 18 miles north of Independence, California. Take US-395 north for 14.2 miles, then right at Aberdeen Station Road for four miles.

Clair Camp – A short drive up Pleasant Canyon from Ballarat, Clair Camp was near the site of Henry Ratcliff’s Never Give Up Mine and the Montgomery brothers’ World Beater Mine, both of which began in 1896. The South Park Mining District was formed the same year. The two mines set up a camp at Post Office Springs about a quarter of a mile south of where Ballarat would soon be established. The camp soon became a town with a Blacksmith, assay office, and other businesses. Before long, the two mines employed about 200 men, and the small camp could no longer accommodate many people. It was then that Ballarat was established. However, by 1905, the Ratcliff Mine suspended operations, and the Montgomery brothers moved on to other mining successes at Skidoo. In 1930, a man named W.D. Clair bought the Ratcliff Mine and began to work the tailings, successfully bringing out another 60,000 in gold ore. At that time, the site was named Clair Camp.

Clair Camp is located on the Pleasant Canyon Loop Trail, about six miles east of Ballarat. The mill site and living quarters of the Radcliffe Mine are located here. The mine itself is located on top of the hill to the southeast. The tram towers and cables leading to the mine are still visible. When the camp continued to have a caretaker, it was very well-kept. However, since then, the area has been damaged by vandals.

Coso Junction – Also called Coso and Oasis, this place started in March 1860 when Dr. Darwin French and his companions began exploring the Coso Springs area. Though they were trying to find the Lost Gunsight Mine, one party member, a prospector named M.H. Farley, found rich silver and gold ore instead, which assayed over 1,000pertoninsilverand1,000 per ton in silver and 1,000pertoninsilverand20 per ton in gold. Soon, Farley and others established the Coso Gold and Silver Mining Company. Dr. Samuel Gregg George led a second group of prospectors. W. I. Henderson discovered and named Telescope Peak and was among the first white men to view the hot mud springs at Coso. By June, some 500 men had stormed the area, and several claims were staked with some mines assaying ore at 2,000ormoreofsilverperton.TheCosoMiningDistrictwasborn,andbeforelong,severalcompaniespromotedstocktoraisecapital.However,thedistrictwasplaguedfromthestartbyunfriendlyIndianswhohadlongvisitedthehotsprings.AfterseveralbattleswiththeIndians,thewhiteminerseventuallyabandonedCoso.MexicansreorganizedthedistrictsinMarch1868,andsporadicproductioncontinuedthroughthe1890s.Inthe1930s,anotherflurryofactivitytookplacewhenmercuryorewasmindedforaboutadecade,takingoutabout2,000 or more of silver per ton. The Coso Mining District was born, and before long, several companies promoted stock to raise capital. However, the district was plagued from the start by unfriendly Indians who had long visited the hot springs. After several battles with the Indians, the white miners eventually abandoned Coso. Mexicans reorganized the districts in March 1868, and sporadic production continued through the 1890s. In the 1930s, another flurry of activity took place when mercury ore was minded for about a decade, taking out about 2,000ormoreofsilverperton.TheCosoMiningDistrictwasborn,andbeforelong,severalcompaniespromotedstocktoraisecapital.However,thedistrictwasplaguedfromthestartbyunfriendlyIndianswhohadlongvisitedthehotsprings.AfterseveralbattleswiththeIndians,thewhiteminerseventuallyabandonedCoso.MexicansreorganizedthedistrictsinMarch1868,andsporadicproductioncontinuedthroughthe1890s.Inthe1930s,anotherflurryofactivitytookplacewhenmercuryorewasmindedforaboutadecade,takingoutabout17,000 in ore. Today, nothing is left of the settlement, and the Coso Hot Springs lies a boundary fence of the United States Naval Weapons Center at China Lake.

Cottonwood Charcoal Kilns.

Cottonwood Charcoal Kilns – The incredibly rich silver and lead deposits at Cerro Gordo not only created the need for the kilns near Olancha, California, but also created many of the historic towns around Owens Lake, including Swansea, Keeler, and Cartago. In June 1873, Colonel Sherman Stevens built a sawmill and flume on Cottonwood Creek high in the Sierras above Owens Lake. The flume connected with the Los Angeles Bullion Road, and the lumber from the flume was used for building the mines and buildings in the area. More wood was turned into charcoal in these kilns before being hauled to Steven’s Wharf on Owens Lake. There, it was put on the steamers, the Bessie Brady or the Mollies Stevens, and hauled across the lake before being loaded into wagons. Hauled up the Yellow Grade Road to the Cerro Gordo Mine high in the Inyo Mountains above Keeler, the charcoal was used in M. W. Belshaw’s furnaces for production. The wagons then took the bullion out by the reverse of this route on Remi Nadeau’s Road headed to Los Angeles. Located near the west shore of Owens Lake, two kilns continue to stand after all these years. They are fenced off to keep the vandals away. They are located 14.4 miles south of Lone Pine on U.S. Highway 395.

Darwin, California – Sitting on the western outskirts of Death Valley in Inyo County, California, tiny Darwin, a semi-ghost town today, was once the largest city in the county. The settlement started in early 1860 when a prospecting expedition led by Dr. E. Darwin French set out from Visalia, California, searching for the Lost Gunsight Mine. This place had long been referred to as “Silver Mountain.”

Death Valley Junction, 1935.

Death Valley Junction, California – First called Amargosa, meaning “bitter water” in the Paiute language, this tiny town in the Mojave Desert is today home to less than a half dozen people. Getting its start as a borax mining community, several historic buildings continue to stand today, including the Amargosa Hotel and Opera House, which still caters to visitors today.

Dolomite, California – Located at the southern tip of the Inyo Mountain range, a high-quality deposit of dolomitic limestone was first discovered in 1862. However, its remote location delayed development until 1883, when the Carson & Colorado Railroad was constructed. Drew Haven Dunn filed a mining claim two years later, and the Inyo Marble Company opened a quarry. Soon, a settlement grew up around the mine, named after minerals that had been mined in the area. The marble continued to be mined and, in 1959, was purchased by Premiere Marble Products. It sold again in 1992 to F.W. Aggregates, which continues operations today. Surveys reveal that the dolomite deposit is approximately seven miles long and 1,400 feet deep, giving it a virtually unlimited supply for many years to come. It is the largest dolomite marble mine in the United States. Producing marble in several colors, its final product is used in terrazzo flooring, roofing, landscaping, and chemicals. The mine is located on private property off of California State Route 136 between Lone Pine and Keller, California, at the north end of Owens Lake. A few buildings from the old townsite still remain, but the property is posted “no trespassing.”

Dublin Gulch, California – Located in Shoshone, California, there are old carved residents and cave-dwelling in the clay cliffs, which have been used throughout the mining days of Death Valley. In the early 1900s, building materials and money were in short supply, so several carved dugouts on both sides of Dublin Gulch. Warm in the winter and cool in the summer, some dugouts have chimneys, doors, split levels, and a garage. The gulch is thought to have been named by a former resident of an area near Butte, Montana, where he once lived. Many famous people in Death Valley history were said to have used these cave dwellings, including Shorty Harris and the Ashford brothers. A graveyard can also be found here. It is located just off Highway 127 and Highway 178 toward Pahrump.

Dunmovin, California – Located south of Olancha, just three miles north of Coso Junction along California’s Scenic Highway 395, Dunmovin was first called Cowan’s Station in the early 1900s after homesteader James Cowan. It first served as a freight station for silver ingots being transported from the Cerro Gordo Mines to Los Angeles. In the early 1900s, the Los Angeles Department of Water & Power piped in water from springs located in Talus Canyon, which sit on the property. However, the department was also in the process of constructing an aqueduct, which was completed in 1913. When the water department abandoned the pipeline, Cowan’s partner, Charles King, filed on it. Later, Charles and Hilda King bought out Cowan in 1936 and changed the town’s name to Dunmovin’. Soon, enough settlers were in the area to justify a post office opening in 1938. However, it lasted just three short years and closed in 1941. However, the town sported a roadside service station, store, tourist cabins, and cafe in an old cookhouse. The property was sold in 1961, and the new owners continued to operate the cafe and store for many years. Situated along what was then the main route between Los Angeles and Reno, the site, no doubt, served travelers along the highway well. However, all businesses are closed today, and the site is abandoned.

Eagle Borax Works, California – A small-scale borax operation started by a Frenchman named Isadore Daunet in 1881. Between 1882 and 1883, the company shipped 260,000 pounds of borax. However, sweltering summer heat and intense competition soon caused the company to fail in 1884. The failure of the company, as well as personal setbacks, resulted in Daunet’s suicide. With its isolated location, distance from main transportation systems, and the daily hardships involved in working under uncomfortable desert conditions, it is amazing that the borax works succeeded. It is located south of Bennett’s Well, about 12 miles southwest of Badwater Road. Only low foundations remain today.

Echo, California – One of several mining camps located in Echo Canyon, prospectors began to climb the Funeral Range looking for promising outcrops after the discoveries at nearby Lee, California. Most of the focus centered on the lower reaches of Echo Canyon in the new camp of Schwab and at the Inyo Gold Mining Company nearby. However, in March 1907, the owners of the Lee Golden Gate Mining Company established another settlement on their claims. Called Echo, the owners began to promote the town and sell lots. But, the town never amounted to much other than a few tents due to the lack of water, wood, and electricity. Today, only a practiced eye can still see a few leveled tent sites. Echo was located at the head of Echo Canyon, overlooking the Amargosa Valley, about halfway between Schwab and Lee. An old road to the old townsite travels southwest of Lee for about four miles and requires a 4-wheel drive.

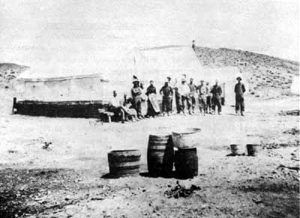

Patsy Clark’s Funeral Creek Copper Mine in its earliest days.

Emigrant Springs, California – An early camp of the Wildrose Mining District, by the summer of 1906, it was projected to be a great mining camp as it had good ore showings in the surrounding properties that were attracting much investment capital. Thirty men were employed in the area, and there was talk of erecting a twenty-stamp mill. At this time, the biggest project under contemplation was constructing a road from Keeler to Emigrant to replace the over-100-mile-long Johannesburg-Emigrant supply route. At this point, both Harrisburg and Skidoo were extremely busy, ensuring some longevity for the Wild Rose District. A six-horse stage was running between Ballarat and Emigrant Springs twice a week, with a saloon, grocery store, corral, and restaurant. Soon, Emigrant Springs developed into a supply point for Skidoo and Harrisburg, with freight teams arriving daily from Johannesburg. By early 1907, the Skidoo water pipeline was still not finished, and water continued to be hauled in wagons from Emigrant Springs by ten-horse teams and was sold for $4 a barrel or three to ten cents a gallon or higher to the townspeople. By then, the camp included several framed tents with traveler accommodations: a store, a saloon, a lodging house, and a restaurant. In August 1908, 3-4 miles of the Emigrant Wash Road were completely obliterated by a cloudburst, the road being five feet deep in water and carrying 50-100-pound boulders. The townsite was located in Emigrant Wash, about seven miles northwest of Harrisburg, California. There are no camp remains, but mining remains can be seen in the area.

Furnace, California – Part of the Greenwater District mining boom, one of the most spectacular in the history of Death Valley mining, several towns started in the district, including Furnace, Greenwater, Kunze, and Ramsey. Furnace was initially known as Clark’s Camp after Patrick “Patsy” Clark, a well-known copper mining operator from Spokane, Washington. When two miners uncovered rich surface croppings of what was thought to be an immense copper belt, the boom began.

Furnace Creek Inn, California – Beginning as accommodations for Pacific Borax Company employees, it was later developed as a tourist destination. Today, it is part of the Furnace Creek Resort. More …

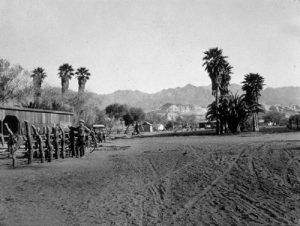

Furnace Creek Ranch in its early days, Death Valley, California.

Furnace Creek Ranch, California – Starting out as a supply point for William T. Coleman’s borax mines, the area was developed into an oasis. Later, it became the property of the Pacific Borax Company. Today, it is part of the Furnace Creek Resort. More…

Gold Hill Mining District, California – Located in the southwest corner of Death Valley National Park in the Panamint Mountain Range, Gold Hill once had several operating mines in the area.

Goldbelt Spring, California – A spring located southeast of Teakettle Junction, it had been long used by Shoshone Indians before prospectors began to comb the area. Miners later used it to search for talc and chrysotile asbestos as a base camp. Gold was first discovered by famed prospector Shorty Harris a few miles south of the actual spring. Though there was talk of building a townsite, the ore wasn’t sufficient to justify one. Harris also discovered tungsten here in 1915. In the 1940s, talc was discovered and mined in various locations, though this never amounted to much. Over the years, several small mines were developed, but none were major operations. Today, the area provides glimpses of flattened buildings, and the spring is marked by an old dump truck.

Gold Valley, California – The rush to the Willow Creek District opened numerous small mines and introduced a townsite battle to the area. The Goldsworthy brothers, who were responsible for one of the bigger gold strikes, announced the formation of the Gold Valley townsite to compete with Willow Creek. These brothers did not think small, and when the Inyo County Board approved the plat of their townsite of Supervisors, it showed an immense camp of ninety-six blocks, with over 1,200 lots surveyed and ready for sale. More…

Grant, California – A small community located about 1½ miles south of Olancha, this place once served the many travelers making their way along U.S. High 395 to and from the Eastern Sierras. A market, gas station, and hotel once operated here, and pack trips could be taken from trailhead points west of the community into the headwaters of the Kern River. A few old buildings continue to stand at the old rest stop including the market and a gas station.

Greenwater, California – Located 5.5 miles north of Funeral Peak above southeastern Death Valley, the Greenwater District was established around a rich copper strike in 1905. There were actually three town sites in the district in the beginning — Furnace, Kunze, and Ramsey, which, combined, are the history of Greenwater itself. The population grew to about 2,000 people during its peak heydays. In 1907, all three town sites were consolidated at the Ramsey site, which was renamed Greenwater. Even though water had to be hauled in and sold at the price of $15 a barrel, the district bloomed briefly as a potential copper mining area from 1905-1908. It was best known for its lively magazine, The Death Valley Chuckwalla. However, when the mines failed to live up to the expectations of their investors, they were abandoned, and the people left for other areas. In May 1908, the Greenwater post office closed, and the next month, there was only one store and saloon left — the Furnace Mercantile Company run by Ralph Fairbanks. When he left the following year, he hauled the last of Greenwater’s buildings to the railroad siding at Shoshone. By 1909, all mining in the area collapsed without ever showing a profit. Today, the old town sites of Furnace and Greenwater contain nothing but rubble. However, Kunze, which was the original site of Greenwater before its move three miles west to the Ramsey site, has more extensive ruins, including a stone dugout house. Greenwater is located in the southeast corner of Death Valley National Park, about 14 miles south of the intersection of CA-190 and Furnace Creek Wash Road.

Greenwater Mining District – Greenwater Valley was the site of one of the most spectacular booms in the history of Death Valley mining. Within a year and a half from the beginning of the rush to Greenwater, the deserted desert was home to over 2,000 inhabitants in four towns, 73 incorporated mining companies, and was the focal point of over 140 million dollars worth of capitalization. More…

Harmony Borax Works by Dave Alexander.

Harmony Borax Works (1881-1888) – The central feature in the opening of Death Valley and the subsequent popularity of the Furnace Creek area, the plant, and associated townsite played an important role in Death Valley’s history. Borax was first discovered in Death Valley in 1881 by Aaron and Rose Winters, whose holdings were immediately bought by

William T. Coleman and Company for $20,000. He subsequently formed the Greenland Salt and Borax Mining Company, which, in 1882, began operating as the Harmony Borax Works. A small settlement of adobe and stone buildings was built, plus a refinery. When in full operation, the Harmony Borax Works employed 40 men who produced three tons of borax daily. During the summer months, when the weather was so hot that processing water would not cool enough to permit the suspended borax to crystallize, Coleman moved his workforce to the Amargosa Borax Works near present-day Tecopa, California. Coleman also immediately purchased the Greenland Ranch (later known as the Furnace Creek Ranch) to the south, making it a supply point for his men and stock. There, he developed a virtual oasis from water that flowed from Furnace Creek.

Getting the finished product to market from the heart of Death Valley was difficult, and an efficient method had to be devised. The Harmony operation became famous through the use of large mule teams and double wagons, which hauled borax over the long overland route. The romantic image of the “20 mule team” persists to this day and has become the symbol of the borax industry in this country.

After only five years of production, the Harmony plant went out of operation in 1888 when Coleman’s financial empire collapsed. Acquired by Francis Marion Smith, the works never resumed the boiling of cottonball borate ore and, in time, became part of the borax reserves of the Pacific Coast Borax Company and its successors. On December 31, 1974, the site was placed on the National Register of Historic Places. Managed by Death Valley National Park, the site displays ruins of the old refinery, outbuildings, and a 20-mule team borax wagon. It is located about a mile north of the Furnace Creek Visitor Center in Death Valley along Highway 190.

Harrisburg Camp, 1908.

Harrisburg, California – This camp was formed after a free-gold discovery by Pete Aguereberry and Shorty Harris in the summer of 1905. Originally, this town was called Harrisberry to capitalize on ShortyHarris’s fame. History is unsure as to whether Aguereberry or Harris made the original find, but when Shorty retold the story, he called it Harrisburg, and the name stuck. Pete Aguereberry, one of the original strike finders, spent 40 years working his claims in the Eureka Mine. It was a tent city that grew to support a population of about 300. Today, the area is dotted with mining remains and still sports Aguereberry’s old home and mine. There is nothing left of the townsite itself. Located in Death Valley National Park at an elevation of about 6,000 feet, the remains are located about two miles down the dirt road to Aguereberry Point off Highway 178. More…

Ibex Springs 1962.

Ibex Springs, California – One of the most extensive ghost towns in Death Valley, this was first the site for a copper, silver, and gold mine discovered in 1881. In 1883, a stamp mill and smelter were built to process the Ibex Mine ores. The mine, however, was played out by the turn of the century. However, in 1907 it was revitalized as a mining camp for silver mines. This was short-lived, however, until talc was discovered in the 1930s. A man named John Moorehouse later filed 16 claims and started the Moorehouse Mine, which operated in the 1950s. The mine yielded almost 62,000 tons of talc before it played out in 1959.

Today, the vast majority of the camp remains date from the 1950s, including numerous buildings and mining ruins. However, the 1883 stamp mill ruins and smelter can also be seen. The area also has old Indian trails and more than two dozen ancient Indian “sleeping circles.” The old mining site is located 5.3 miles due west of CA-127, about two miles south of Ibex Pass. A four-wheel-drive vehicle is required.

Inyo Mine,1938.

Inyo Mine, California – A gold mining operation established in 1905 in the Echo Mountain Mining District was short-lived, closing just two years later during the financial panic of 1907. However, the mine was revived in 1928 and operated until 1941. Today, the mine displays some of the most extensive remains in Death Valley National Park, including several cabins and the ruins of the mill. It is located nine miles east of CA-190 on Echo Canyon Road.

Kasson, California – An early mining camp that was said to have been located about 12 miles northwest of the original site of Tecopa, this place was one of the many stock swindles in the American West. Located in the Mineral Basin District, a man named Barton O’Dair had a claim called the Vulture, which he had opened with the financial help of Los Angeles investors, including attorney John S. Thompson. When they found the ore wouldn’t pay, they looked for a buyer for the property. Finding interest in a Milwaukee man named Amasa C. Kasson, he, along with the help of original investor and attorney John S. Thompson, organized the Gladstone Gold and Silver Mining Company in June 1879. Twelve million dollars in stock was soon advertised for sale, which called for large development, including a 60-stamp mill and bullion production of nearly $2 million per year. A town called “Kasson” was developed on paper, including a post office. However, just a few months later, when Washington D.C. found out no one was living there, they withdrew the post office authority in November 1879. Though Kasson appeared on maps for about ten years, a town never developed, there is evidence that a place called the “Gladstone Mine” existed. There was obviously some mining activity that took place here in the Ibex Wildnerness because today, there are a few remains, including several small stone buildings without roofs and a cave at the top of the hill that has a couple of entrances.

Keane Springs, California – Located in northeast Death Valley, Keane Springs started during the Rhyolite boom in 1906 because of its good water source. This inspired a group of promoters to establish a townsite. Though it initially did well supporting the Keane Wonder and Chloride Cliff Mines, both operations established their own camps. The springs slowly declined back into a favorite watering hole and stopover for travelers. It was almost entirely wiped out by a flood in 1909. Today, its most prominent remains are the water tank, the ruins of the pumping machinery, and a few low stone walls. To get to the site from Beatty, Nevada, travel west on NV-375 for 15.8 miles. Then turn left (East), and travel two miles to a road barrier on left. From here, it is a .75-mile hike down the barricaded road toward the big willow tree. The townsite is in the wash below the spring.

Keane Wonder Mine, California – Founded in 1903, the Keane Wonder Mine was one of the most successful gold mines in Death Valley. Its initial major operations occurred from 1908-1916, and a post office was established by 1907. Two camps grew up around the mine, including Keane Springs and Chloride City, California, but both towns failed quickly. Despite the failure of the towns, the mine continued to be profitable throughout the Panic of 1907. It was thought that it had been tapped out by 1912. However, mining operations were revived in the 1930s, and most of the extensive remains date from that period. There are remains of the mill, a 1,400-foot tramway, and other mining ruins. To see the site, drive the Beatty Cutoff Road 5.7 miles north from Highway 190 to the marked dirt road for Keane Wonder Mine. Continue 2.8 miles to the parking area. The road is typically rough and may require a high-clearance vehicle with thick tires.

The Keane Wonder Mill and Tramway Area, located near the parking area, is very accessible. A short walk up the trail at the end of the road will provide views of the lower tram terminal and the first few tram towers. Walk along the mining road for views of the aerial tramway. The steep trail climbs 1,500 feet in 1.4 miles to the upper tramway terminal and, just beyond it, the Keane Wonder Mine.

The Keane Wonder Mine in Death Valley National Park. Photo by Gianfranco Archimede, 2000.

Keane Wonder Mine by Gianfranco Archimede, 2000.

Kearsarge, California – There were actually a couple of locations called Kearsarge. Still, the Kearsarge Mine was situated high on Kearsarge Peak on the east flank of the Sierra Nevada about eight miles west of Independence, California. A trail was first built up the east side of what is now known as Kearsarge Pass in the summer of 1864. When gold was found by this party of prospectors, who held Union sympathies, they named their find after the U.S.S. Kearsarge, a famous Union warship. Several claims were staked, including the Kearsarge, Silver Sprout, Virginia, and Rex Montis, which proved to be the principal gold source, while the others produced silver. The find attracted several investors who soon formed the Kearsarge Mining Company, and by August 1865, they had driven a 50-foot tunnel into the mountain’s southeast side, hitting $650+ per ton of ore. The camp that grew up around the mining operations was called Kearsarge City. As word leaked out, the camp grew, and by October, more than 1,000 residents had hoped to claim the Inyo County seat. However, when the election was held in January, Kearsarge lost out to Independence.

Kearsarge Pinnacles.

During the bitter winter of 1866-1867, Kearsarge had all but emptied out except the crews working the mine. That March, an avalanche buried the camp, destroying several buildings, injuring residents, and killing the wife of a mine foreman. The citizens then decided to relocate to Onion Valley. Though the mines were producing well, litigation plagued them, and the Kearsarge Company soon found itself about $15,000 in debt. In 1867, the mine was sold, and the operation slowed down. Though it would change hands over the next several years, it would continue operations through 1883. Several attempts were made to reopen the mines, but all failed due to the isolated location. During World War I, the machinery was scrapped. However, mine was worked briefly again in the 1920s when several cabins were built. These were later moved to Independence. There are no remains of the two camps today, which require a high-country hike to access the area.

Far below the peak, just 4.5 miles east of Independence, was another place called Kearsarge Station, a stop on the Southern Pacific Railroad. Also called Citrus, a post office operated here from 1888 to 1905 and again from 1907 to 1910. There are no remains here either.

Keeler, California – Not quite a total ghost town, Keeler, located on the east shore of Owens Lake, is still called home to about 60 people. The settlement started in 1872 when the Lone Pine earthquake rendered the pier at nearby Swansea inaccessible by uplifting the shoreline. The place was first known as Cerro Gordo Landing and served as a shipping point for the prosperous mines at Cerro Gordo. When the railroad began to come through, the station was called Hawley. The Owens Lake Mining and Milling Company built a new mill at the site in 1880, and a town was laid out by the company agent, Julius M. Keeler, for whom the town of Hawley was later renamed.

A 300-foot wharf was constructed at Keeler so that ore could be shipped across the lake, cutting days off when it would take a freight wagon to go around it. The steamship Bessie Brady was utilized to take ore from Keeler across the lake to the town of Cartago, where it would then be shipped to Los Angeles.

Keeler Depot.

Carrying 700 ingots at a time, the Bessie Brady would take about three hours to cross the lake. In 1883, the Carson & Colorado Railroad constructed a narrow-gauge railway to Keeler; a post office was opened the same year. The success of the Cerro Gordo mines caused Keeler to boom until silver prices plummeted in the late 1800s. The post office closed in 1898.

However, a second zinc mining boom began in the early 1900s, bringing new life to Keeler. A tramway down to the town was constructed from the Union Shaft at Cerro Gordo. The mining continued consistently until 1938 when the mines were closed. Sporadic surges would be made over the next decades, but by the 1950s, all mining had ceased. Train service to Keeler was discontinued in 1960, and the following year, the tracks were removed.

Water diversion from the Owens Valley to the City of Los Angeles in the 1920s caused Owens Lake to eventually dry up, making the lake bed one of the nation’s dustiest places. Many of the residents moved away, and though efforts have been made over the years to reduce the problem, few people remain. However, a post office was reopened sometime during the second mining boom, and it still operates today.

Today’s semi-ghost town continues to sport several buildings from its previous heydays, including the old train station and deteriorating homes and business buildings. Many no-trespassing signs are posted throughout the area. Keeler is located 11.5 miles southeast of New York Butte, California.

Keynot, California – Situated on the east side of the Inyo Mountain Range north of Beveridge, are the Keynot group of claims. Seven mines operated here, and were the best in the Beveridge district. Tunneling as deep as 1,800 feet, pack mules carried the ore to a mill in Beveridge Canyon. A gasoline hoist and compressor were implemented on top of the Inyo Crest. The area is dotted with old mines and remnants, but access should only be made by experienced backpackers.

Kunze, California – The original Greenwater site, Kunze was founded by Arthur Kunze, a prospector looking for copper in 1906. Two more townsites, Ramsey and Furnace also sprouted up. All were consolidated as Greenwater the following year. See full article HERE.

Laws Railroad Museum, photo courtesy California Day Trips.

Laws, California – Formerly called Bishop Creek Station, the town started in 1883 as a depot originated in Nevada. Growing into a transportation hub servicing the mines and agricultural areas, it gained a post office in 1887. In 1900, the Southern Pacific Railroad purchased the Carson & Colorado line and renamed the station in honor of a railroad official. In 1908, the railroad expanded its line from Laws to the north, making direct rail connections from Owens Valley to the north and south. In 1938, the Southern Pacific closed the narrow gauge line to the north, but as the northernmost terminus of Owens Valley, Laws remained busy for another 20 years.

That prosperity ended in 1960 when the railroad closed the remaining portion of its line between Laws and Keeler. The post office closed its doors in 1963, and Laws was destined to be a true ghost town. Instead, the City of Bishop and Inyo County established a railroad museum at the site and later moved various buildings to Laws. It now serves as a museum that typifies a typical turn-of-the-century town. See full article HERE.

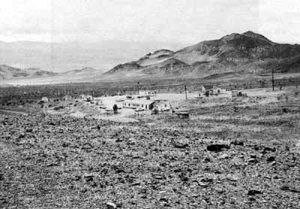

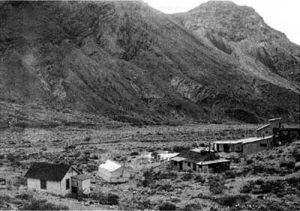

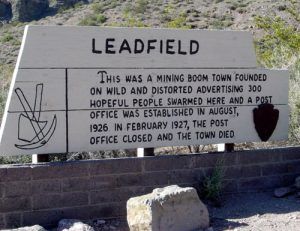

Leadfield – Copper and lead claims had been filed in the Leadfield area as early as 1905, but it wasn’t until 1926 that the area was heavily mined. In February of that year, Charles C. Julian, a flamboyant California promoter, became president of the town’s leading mining company, the Western Lead Mines. Julian’s promotions were responsible for bringing great numbers of people into the area, and in April 1926, the town was laid out with 1749 lots. The financial downfall of Charles Julian and the playing out of lead in one of the main mines led to the end of the town. Today, the area is scattered with mines, dumps, tunnels, and prospect holes. There are remains of wood and tin buildings, as well as a dugout and cement foundations of the mill. It is located on the Titus Canyon Road. This one-way, high-high-clearance, unpaved road sometimes requires 4-wheel drive.

Leadfield – Copper and lead claims had been filed in the Leadfield area as early as 1905, but it wasn’t until 1926 that the area was heavily mined. In February of that year, Charles C. Julian, a flamboyant California promoter, became president of the town’s leading mining company, the Western Lead Mines. Julian’s promotions were responsible for bringing great numbers of people into the area, and in April 1926, the town was laid out with 1749 lots. The financial downfall of Charles Julian and the playing out of lead in one of the main mines led to the end of the town. Today, the area is scattered with mines, dumps, tunnels, and prospect holes. There are remains of wood and tin buildings, as well as a dugout and cement foundations of the mill. It is located on the Titus Canyon Road. This one-way, high-high-clearance, unpaved road sometimes requires 4-wheel drive.

Lee, California/Nevada – Also called Lee’s Camp, this place started after the wild Bullfrog rush in 1904, causing prospectors to flock over the region. Two of these prospectors were ranch brothers named Richard and Gus Lee, who decided to leave their ranch at Resting Spring, California, and give prospecting a try. With the help of a man named Henry F. Finney, they soon found two gold ledges in November 1904, which they named the State Line and Hayseed Mines, just inside California. As word got out, hundreds more flocked to the area in search of their fortunes, and the Lee Mining District was formed in March 1905. A few months later, in October, a similar condition existed on the west side of the Funeral Range, and the Echo Mining District was organized. The two districts were then merged and became known as the Echo-Lee Mining District. Another man named David M. Poste had found gold in the low hills east of the original Lee Camp in Nevada, and the Poste Mining District was formed on that side of the state line. Before long, two townsites were created to cash in on the boom, one in California and the other in Nevada. Both were called Lee, after the Lee brothers who had started the rush.

Within sight of each other, straddling the state line, another addition grew up between the two called the Lee Annex. As the two townsites were developed in January 1907, the Bullfrog Miner observed, “It is claimed that a camp is never fairly certain of a good future until it has a townsite fight,” and such a fight was now on. The Nevada company promised to soon have a telephone connection, a corral, a feed yard, a restaurant, a rooming house, and a saloon. In California, by February, the Lee townsite boasted a restaurant, a rooming house, a saloon, and a general store. In the end, Lee, California, would win out when the principal owner of the Hidden Treasure Mining Company and Lee, California promoter, struck pure water about three miles east of Lee and immediately announced plans to lay a pipeline and build a pumping station to bring the water into Lee, California. The district peaked with about 600 residents the same year and gained a post office.

However, by late in the year, Lee began to feel the effects of the Panic of 1907, and the decline began. Storekeepers and other merchants, who depended upon a steady cash flow to stay solvent, began to leave in the first half of 1908. However, there were still eleven mining companies active in the Echo-Lee District. By June, Lee had dwindled to only three stores, a saloon, and a restaurant. Still, the town and the mines continued. But not for long. The post office closed in 1912. Today, there is little left but empty mine shafts and tunnels, a few stone foundations, an old stone bridge, dugouts, a set of stone walls, and much debris. It is located near the Nevada state line, at the eastern foot of the Funeral Range, 30 miles south of Rhyolite.

Lila C Mine 1943.

Lila C Mine – This mine was purchased in the early 1880s by William T. Coleman, who named it for his daughter. Coleman never developed the mine and lost it to Francis Smith when his finances collapsed in the late 1880s. Smith incorporated it into the Pacific Coast Borax Company but did not immediately work the mine as he was focused on the mine in Borate. However, when those ores were nearly exhausted, the company turned its attention to the Lila C, which would soon prove to be one of the richest in Death Valley. Development began in 1903, and they soon discovered three colemanite beds 6-18 feet wide and at least 2500 feet long. Steam traction engines hauled ore to Manvel, 100 miles away, until 1907, when the Tonopah & and Tidewater Railroad reached the area. A spur from the railroad was then built to the Lila C, allowing for much cheaper transportation costs.

At that time, the camp’s name was changed to Ryan in honor of John Ryan, a borax company executive. That same year, a post office opened. The camp of Ryan peaked at about 200 people. The opening of the Lila C. Mine caused the price of borax to drop 2 cents a pound to between 4 ½ to 5 ½ cents, causing a shutdown of the mine at Borate and mines in Saline Valley and on Frazier Mountain. Through 1914, the mine would produce over $8 million in borax. With the mine playing out, the company town and its post office were moved to a site called Devair and/or Colemanite. It, too, was called Ryan, and the old Lila C was then referred to as “Old Ryan.” The Lila C totally stopped production in January 1915. It is located 6.25 miles southwest of Death Valley Junction. There is nothing left today except tailings.

Little Lake California.

Little Lake, California – Still inhabited until the last few decades, Little Lake started as a rest stop for travelers long ago. Once called Little Owens Lake, it was first a seasonal marsh until it was dammed in 1905 as a part of the Los Angeles Aqueduct system. While building the aqueduct, the Southern Pacific Railroad built the “Jawbone Branch” from Mojave to Lone Pine, which was completed in 1911. Standing in stark contrast to the black basalt lava formations surrounding it, the lake soon beckoned entrepreneurs who built a gas station, store, restaurant, and hotel at the south end of the lake. A post office was first opened in 1909, operating for two years, before being moved to Narka. In 1913, it was transferred back. In 1923, the Little Lake Hotel was opened, doing brisk business for tourists and sportsmen heading north to the eastern Sierras or south towards urban Southern California. Old Highway 6/395 once passed right through the town, which thrived in the 1940s-50s. However, in the mid-1960s, the highway was rerouted to the east behind the town, causing fewer visitors to stop. In 1982, the railroad discontinued its line through the community, causing further decline. In 1989, a fire ravaged the hotel’s upper floor, and it was closed. The post office closed its doors for the last time in 1997, and the railroad tracks were torn up the following year. In the summer of 1998, two flash floods wiped out what little was left of the town. Since then, the ruins have been removed, and the old town is nothing but a flat place in the desert today. It was located 38 miles south of Keeler on U.S. Route 395.

Lookout City, California.

Lookout City, California – Lookout City, California, is a former Death Valley settlement located in the Mojave Desert in southern Inyo County. More…

Loretto, California – Loretto was a copper mining region in Death Valley in northern Inyo County. All that is left today are stone walls, mining portals, and mining equipment. More…

Panamint City, California – Once called the toughest, rawest, most hard-boiled little hellhole that ever passed for a civilized town, Panamint City got its start after several bandits, who were using the area as a hideout, discovered silver in Surprise Canyon in 1872. More…

The roofline of Scotty’s Castle shows the Spanish Moorish influences, Dave Alexander.

Scotty’s Castle – Located in Grapevine Canyon, the Death Valley Ranch, more popularly known as “Scotty’s Castle,” was the desert hideaway mansion of Chicago insurance magnate Albert Johnson. Serious construction started in 1925 and continued into the early 1930s. However, Johnson’s insurance company went into receivership in 1933, a victim of the Great Depression, and work on the 8,000-square-foot house was never completed. While Johnson financed the mansion, the site is more closely associated with Walter Scott, who was locally known as “Death Valley Scotty.” Close friends with Johnson, Scott often stayed at the ranch, and after the Johnsons died, he lived there for the rest of his life. Today, it is administered by Death Valley National Park, and the mansion and various outbuildings can be toured. See Full Article HERE. (check if open; read notes at the end of the article about recent flood-closing until 2020)

Skidoo, California – The ghost town of Skidoo, California, in Death Valley, was once a booming mine camp. More…

Willow Creek – The history of the once-promising mining camps of Willow Creek and Gold Valley, situated in Death Valley, California, was the scene of a Greenwater boom in miniature. More…

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated May 2024.

Also See:

Death Valley Ghost Towns & Mines Index

Characters of Early Death Valley

Death Valley Ghost Towns in Nevada

Desert Steamers in Death Valley

See Sources.