Furnace Creek Inn in Death Valley, California – Legends of America (original) (raw)

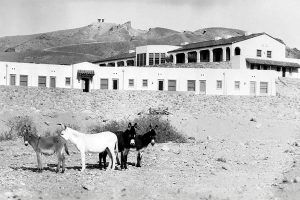

Furnace Creek Inn, 1928

In the 1920s, it became apparent to the Pacific Coast Borax Company that the emphasis of borax mining was swinging away from Death Valley. This left the region with a still-functioning railroad and comfortable living quarters at Ryan, California; it was decided that it might be a good time to start encouraging tourist travel to the area to make some money off these still-usable facilities. Other factors, too, seemed to assure the probable success of such a venture, including tourist travel on the railroads, the success at Stovepipe Wells Resort, and the great valley temperatures from October to May.

The primary concern of the company centered around providing adequate and comfortable accommodations. It was first thought that the natural and easiest solution would be to house people at Furnace Creek Ranch, and plans were accordingly made to add 10-12 bedrooms plus dining facilities.

On further thought, however, this locale seemed too remote from Ryan and thus impractical as a tourist headquarters. After lengthy consideration of alternative locations at Ryan and Shoshone, it was finally decided that the small mound and former Indian ceremonial area at the mouth of Furnace Creek Wash would be an ideal site. Not only was an excellent freshwater supply available 6,000 feet up the wash at Travertine Springs, but the view up and down the valley and of the surrounding mountains was breathtaking. The architect Albert C. Martin was hired to prepare plans for a Spanish-style building, and native Panamint Indians were immediately put to work manufacturing adobe bricks for its construction.

Furnace Creek Inn today, Kathy Alexander.

Construction of the hotel started in September 1926, and its official opening was held on February 1, 1927. However, the structure was only partially finished, and its number of rooms and furnishings soon proved utterly inadequate. At that time, the Inn consisted only of the main building housing a spacious lobby and pleasant dining room, with wings on either side containing bedrooms. In the fall of 1927, five more terrace rooms were added on either side of the parking area, and more construction would continue over the next decade.

The Pacific Coast Borax Company extensively promoted the use of its own standard-gauge Tonopah & Tidewater and narrow-gauge Death Valley railroads to transport tourists to the site. At that time, tourists could purchase a package that included transportation, hotel accommodations for one night at Furnace Creek Inn, meals for two days, and bus tours to nearby attractions for $42.

A generator provided electric power at the Inn in 1929, and water piped from Travertine Springs watered the grounds, gardens, and a date palm grove. Domestic water came from Texas Spring to the northeast and was stored in a reservoir for use by both the Ranch and Inn.

Designed by prominent Los Angeles architect Albert C. Martin and landscape architect Daniel Hull, the 66-room Inn sprawls across a low hill at the mouth of Furnace Creek Wash. With views over Death Valley and the Panamint Mountains to the west, the Inn’s location was well chosen but rather conspicuous. In less skilled hands, the Inn could have been a visual imposition on the otherwise natural landscape, but Martin and Hull created a masterpiece in harmony with history and scenery. Red tile roofs, stucco exteriors, archways, arcades, and towers were inspired by the old Spanish Missions on the California Coast. The Inn’s wings wrap around a lovely garden of palms and flowing water, a nod to both mission courtyards and the Hollywood image of a fantasy desert oasis. The lower levels constructed of local stone seem to be a natural extension of the alluvial fan pouring out of Furnace Creek Wash. The colors of golden stucco, russet roof tiles, and turquoise window trim all match the badlands at Zabriskie Point and Artists Drive.

Eleven-passenger Union Pacific tour bus.

Even with amenities such as a warm spring-fed swimming pool, tennis courts, and a nearby golf course, the Borax Company realized the primary attraction for their resort was its location in Death Valley. An oasis of comfort and luxury in a wild and desolate desert proved irresistible to tourists. The mining company understood Death Valley’s rustic charms could be easily lost without some preservation. National Park status for Death Valley would limit damage from mining and control excessive development (and competing hotels.) Tourists who were hesitant to visit such a morbid-sounding place as Death Valley would know it must be worth visiting if it was included with the nation’s other crown jewels like Yosemite, Yellowstone, and Grand Canyon. It would become a “must-see.” As a result, the company began to lobby for the region to be protected by the Federal Government.

Using media to spread the word of Death Valley’s wonders and start grass-roots support for the protection of Death Valley, the company promoted magazine and newspaper articles, as well as a successful radio program — Death Valley Days. In February 1933, President Hoover signed a proclamation creating Death Valley National Monument.

With the proclamation of Death Valley as a national monument in February 1933, the federal government constructed highways in Death Valley that the California State Highway Commission took over. The improved roadwork immediately generated heavy auto travel, causing the Union Pacific Railroad to pull out of the tourist trade in the early 1930s.

In 1956 Fred Harvey, Inc. took over management of the Furnace Creek Inn and Ranch for the borax company and, in 1969, purchased the properties outright.

In 1994 Death Valley was designated a National Park. Today, the Furnace Creek Inn is still an oasis in the desert. Thanks to the foresight of the Pacific Coast Borax Company and the National Park Service, guests can enjoy the same untrammeled beauty of Death Valley that guests did back in 1927. The Xanterra Corporation owns the property as part of the Furnace Creek Resort.

Furnace Creek Inn gardens, Death Valley, California, by Carol Highsmith.

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated December 2022.

Also See:

Sources:

Greene, Linda W. and Latschar, John A; Death Valley Historic Resource Study; National Park Service, 1979

Death Valley National Park