The California Gold Rush – Legends of America (original) (raw)

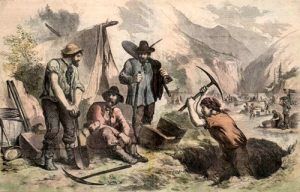

Gold Mining in California by Currier & Ives.

The gold discovery in California wrought immense changes upon the land and its people. With its diverse population, California achieved statehood in 1850, decades earlier than it would have been without the gold.

California Gold Miners.

“Gold! Gold! Gold from the American River!”

— Samuel Brannan, running through the streets of San Francisco waving a bottle of gold dust in the air, 1848

On the cold morning of January 24, 1848, James Marshall, a construction foreman at Sutter’s Mill, inspected the water flow through the mill’s tailrace. The sawmill on the American River banks in Coloma, California, was owned by John A. Sutter, who desperately needed lumber to build a large flour mill. On that particular morning, Marshall found the water to be flowing adequately through the mill and spied a shiny object twinkling in the frigid stream. Stooping to pick it up, he looked with awe at a pea-sized gold nugget lying in his hand.

James Marshall at Sutter’s Sawmill, Coloma, California, 1851.

He immediately visited Elizabeth Jane “Jennie” Wimmer, the camp cook and laundress who had grown up in a prospecting family. Ms. Wimmer used a lye soap solution overnight to verify that the 1/3 ounce nugget Marshall had found was genuine gold. Dubbing it the Wimmer Nugget, which was later appraised at $5.12, Marshall gave it to her on a necklace. It would later be displayed at the Columbian Exposition of 1893.

James Marshall.

Marshall then informed his boss, John Sutter, of his find. Sutter, a German/Swiss immigrant who owned thousands of acres around the Sacramento and American Rivers, had dreams of developing part of his land into a utopian farming settlement named “Nuevo Helvetia” (Spanish for “New Switzerland”). His main compound was known as Sutter’s Fort and had already become a destination for immigrants, including the Donner Party. More concerned with expanding his agricultural empire, Sutter wished to suppress the information about the gold. But such a secret was too big to keep hidden. Before long, a San Francisco newspaper confirmed several reports of gold finds in the area. Miners began to flock to the area, turning it from a sleeping outpost to a bustling center of activity.

Even with the crudest of mining tools, the earliest miners did well. All one had to do was dig down into a placer and wash the pay dirt. The entire gold country was open to all. No taxes were levied on what the miners found. No towns or roads existed in the gold country. Every miner was on his own, and nobody had to work for wages unless he wanted to.

On August 19, 1848, the New York Herald was the first newspaper on the East Coast to confirm a gold rush in California. By December 5, 1848, even President James Polk would announce this before Congress, significantly legitimizing the news.

Sutters Mill, Coloma, California, by Kathy Alexander.

News of gold, free for the taking, continued to spread. The first gold seekers were arriving from outside California by the end of summer. The first immigrants were probably from Oregon, where American farmers had settled since the early 1840s. Next came men from the Sandwich Islands (now Hawaii). In the autumn, new arrivals were coming from northern Mexico, and during the winter, large numbers came from Peru and Chile in South America. Still, there was plenty of gold for all, and fresh discoveries were made daily. The immense extent of the gold deposits was becoming apparent.

As he predicted, when he saw the gold nugget, John Sutter was ruined as more and more agricultural workers left searching for gold, squatters invaded his land, shot his cattle, and stole his crops. Sutter described it this way: “Everyone left, from the clerk to the cook, and I was in great distress.”

Though the great majority abandoned their other activities to search for the precious metal, one enterprising Mormon merchant named Samuel Brannan had a better idea. He bought all the mining supplies he could find and filled his store at Sutter’s Fort with buckets, pans, heavy clothing, foodstuffs, and similar provisions. Then he took a quinine bottle full of gold flakes to the nearest town, San Francisco. He walked up and down the streets, waving the bottle of gold over his head and shouting, “Gold, gold, gold in the American River!” The next day, the town’s newspaper described San Francisco as a “ghost town.” Samuel Brannan quickly became California’s first millionaire, selling supplies to the miners as they passed by Sutter’s Fort.

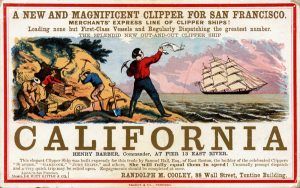

To California during the gold rush.

The gold discovery sparked almost mass hysteria as thousands of immigrants worldwide soon invaded what would soon be called the Gold Country of California. The peak of the rush was in 1849; thus, the many immigrants became known as the ’49ers. Some 80,000 prospectors poured into California that year alone, arriving overland on the California Trail, by ship around Cape Horn, or through the Panama shortcut. Most of them came in one immense wave during mid-summer as covered wagons reached the end of the California trail. At the same time, sailing ships were docking in San Francisco, only to be deserted by sailors and passengers.

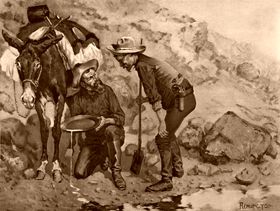

Digging for gold from early dawn until dusk was backbreaking work. The hope of “striking it rich” became an obsession among Forty-Niners. Stories of others who had found their fortune in gold kept driving them on. A rich strike could always follow a streak of bad luck.

Miners prospecting, by Frederic Remington.

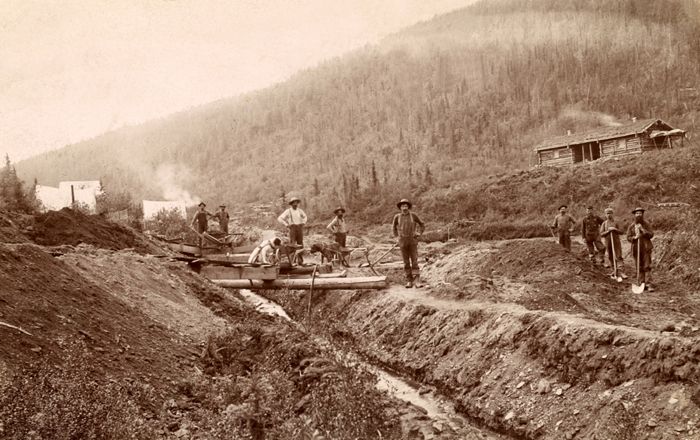

By the 1850s, miners came from Britain, Europe, China, Australia, and North and South America. However, the gold was getting harder to find, and competition grew fierce between the miners. At the same time, merchants raised the prices of mining tools, clothing, and food to astronomical levels. A miner had to find an ounce of gold daily to break even. Most miners barely found enough gold to pay for daily expenses. Nevertheless, it was among the most important eras of migration in American history and led to California’s statehood.

As miners continued to invent faster, more destructive methods of finding gold, the land was ravaged. Hillsides were washed away in torrents of water, and towns downstream were inundated by immense mud floods. Water supplies were poisoned with mercury, arsenic, cyanide, and other toxins. Great forests of oak and pine were leveled for mining timbers.

The gold discovery wrought immense changes upon the land and its people. With its diverse population, California achieved statehood in 1850, decades earlier than it would have been without the gold.

The peak production of placer gold occurred in 1853. Every year after that, less gold was found, but more and more men were in California to share in the dwindling supply. Thousands of disillusioned gold seekers returned home with little to show for their time and glad to escape with their health.

Gold miners in El Dorado, California, about 1850.

After the boom, many miners returned to San Francisco, rich or, more often, broke and looking for wages. Like many cities of the 19th century, the infrastructures of San Francisco and other boom towns near the fields were strained by the sudden influx; leftover cigar boxes and planks served as a sidewalk, and crime became a problem, causing vigilantes to rise and serve the populace in the absence of police.

Instead of returning home, other miners sent for their families, turning to agriculture and other businesses for survival.

The California Gold Rush is generally considered to have ended in 1858 when the New Mexico Gold Rush began. Afterward, California’s hearty pioneers found the land unbelievably productive, and ultimately, the state’s great wealth came not from its mines but its farms.

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated April 2024.

See our California Gold Rush Gallery HERE

Also See:

Gold panning in the American West.

California Ghost Towns & Mining Camps